SHIRTLESS IN MIAMI

For many nights now, this heat has enveloped my body - heat attributed

to the weather of Miami. I live beside the beach of this Latin city, and I'm

sweating profusely. Inside my seaside apartment, I hear the endless rustling

of palm leaves. Below me, on Ocean Drive, people of Latin smiles, Latin bodies,

Latin hairs, Latin loves pass by, their fashionable clothes flow with the sea

wind. Then I hear the sound of a guitar accompanied by a Spanish tune - Besa

me, yes, besa me mucho...; Paloma. There's freedom and wildness in the air.

I stand on my balcony, below me the Miami Shore is settling calmly. The

lights on the Intercoastal's many scattered islets are beginning to shine and

flicker. I pour myself a tequila.

This is the kind of heat that makes one feel good. It's heat coming from

the sea, then it mingles with the heat of the people, then it touches my skin

until I'm all wet with sweat. I sit on my wicker lounge chair, proposing a toast

to the full moon hovering over me.

I stay on my chair to savor this good feeling. After a while, I get bored.

I stand and pull off my shirt. I pause in front of the mirror on my apartment's

wall. I say to myself, "Ah still not bad at all."

I walk on Ocean Drive, side by side with Latinos' shirtlessness, our brown

skins shine under the moon and city lights. Some of the bodies are shaved to

accentuate rippled abdomens. Some bodies are hairy.

Still holding my tequila, I pause by every stall along the beach: Bali's

wood curvings, Russian paintings, gay bookstores and - seashells made in the

Philippines.

I stop by the seashells - I raise one shell necklace before my eyes, the

shells' name comes to my mind instantly. Sigue shells which I used to play sungka

with. I smile at the memory of my childhood.

"El collar es muy magnifico," I say in my basic and twisted Spanish. I

am addressing the Cuban stall owner whom I always greet everytime I pass by.

When one knows how to speak Pampango, like I do, he's not far from being understood

in Spanish no matter how wrong his grammar is.

The Cuban asks me if I like the shell necklace.

"Si," I say. "Cuanto?"

The Cuban smiles, nothing more can amuse a Latino than a twisted, primitive

though somewhat understandable Spanish.

"Un dolar," he says.

"Ay, es muy costosa," I say. "En mi pais, esta collar es un libre siempre,

para jugar por los ninos y ninas."

He giggles at my impossible Spanish. "Que es su pais?" he asks.

"Filipinas."

"Bueno," he says, and he accepts my fifty cents for the shell necklace.

I wear the necklace, swagger like a boy with a newfound toy. I walk with

pride. I am wearing something made in my country. The thought transports me

back to my origin.

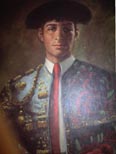

Then a portrait catches my attention. It stands all alone beside a table

inside a ramshackle stall managed by a Hispanic woman. I walk towards it.

Someone taps me by my shoulder. I abruptly turn around.

A man in his forties is smiling at me. "What's happening?" he asks. "Where

have you been?'

I don't know the man but I've heard the same pick-up lines before.

I ignore him. I keep my pace. I want to reach the portrait before anyone

else does.

"Can I walk with you?" the man asks.

"I've just got divorced," I say.

He stops. "Oh, when?"

"This morning," I holler back laughing.

I reach for the portrait in the stall. The Matador on the portrait looks

so strange yet so familiar to me.

"Cuanto es el letrato, aqui?" I ask showing the portrait to the woman.

I'm not even sure if letrato is the right Spanish word for portrait painting.

Hearing my Spanish, the woman beams in a wide grin. "Te gusta?" she asks

pointing at the painting in my hands.

"Si. Cuanto, Senora?"

"Diez dolares," she says.

I attempt to bargain with her a la Divisoria. "Cinco dolares?" I say.

She seems to know the game I'm playing, she plays along. "No. Ocho dolares."

"No. Cinco dolares," I persist.

She smacks her forehead with her hand, shaking her head. "Ay, ay mi hijo,"

she says. She continues to say in Spanish she will lose money if she gives the

painting to me in that price. But I'm quick in pulling my wallet and showing

her my five dollars.

I win.

I walk back to my apartment, a shell necklace around my neck, a big, old,

discarded painting in my one hand, a glass of tequila in the other. My fellow

strollers are bemused by the way I look. I don't care. My apartment is only

two blocks away.

I place the cheap painting beside me in my balcony. I keep staring at the

face of the Matador with a pang of isolation and nostalgia. He looks at me with

sadness and dignity and understanding.

Who is this face? Under it, Don Juan is inscribed. Is he the infamous Don

Juan? Is he a Cuban face? Is he Spanish Spanish?

The Latin heat of Miami envelopes me again. I pour myself another glass

of tequila. I hear the Spanish flamenco tune in a restaurant below me. I stand

to watch the beautiful Miami before me.

This face of the Matador...he looks like my country's history long long

time ago.