Song of the Waters, Chapter One

Copyright 2003 by Zimraphel

“[Círdan] is the Sindarin for ‘Shipwright,’ and describes his later functions in the history of the First Three Ages; but his ‘proper’ name—his original name among the Teleri, to whom he belonged—is never used.” --“Last Writings,” The Peoples of Middle Earth

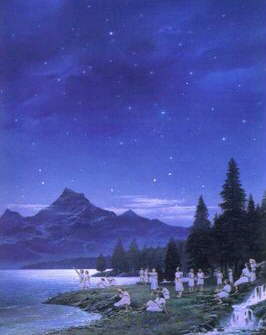

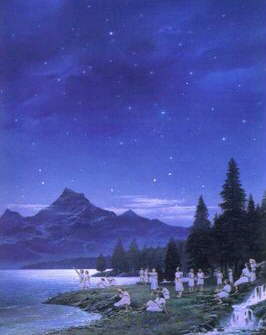

Cuivienen |

“Nowë, go not from the shore but stay where I can see you.”

He turned and looked at his mother, standing in the doorway of their hut, and waved to her. Many times he reminded her that he was nearly grown, but that mattered not to her or his father. “Mark you the shadow-shapes that haunt the hills and stay away from them,” said Mála. “Alata and her child they took, never again to be seen.”

They need not have feared for him, for Nowë had no curiosity about the dark woods or hills that encircled Cuiviénen; he could feel the threat hovering in the air of the forest without having to be told, seeing with his inner sight the evil that lay in wait for him there, and unless it was an excursion with his cousins Elwë and Olwë to climb up for a closer look at the stars, he paid the hills no mind. Rather, his attention turned to the twilit water, enjoying the feel of its silvery coolness ripple around his ankles, peering down to study his reflection framed by the stars.

|

Mother says the song of the waters was the first sound we ever heard, just as the stars were the first thing we ever saw. There is something special in that, something…ai, I do not have a word for it. But my life I will spend by the waters, he thought, with all the certainty of one who knew.

Olwë taught him to fish and to swim, though his mother did not like him to go too far from shore. For what lurked in the woods might dwell also in the deeper waters, she said, and bade him come indoors whenever rumor came of strange creatures abroad.

Nowë could have told her that in the water there was no darkness; its depths were clear and cool, watched over by some nameless presence that caressed his limbs and stirred tendrils of his silver hair as he glided through the deep. No evil would come there, where the light of the stars met the water. And, too, he could have told her that not all creatures that came near Cuiviénen were ones of darkness. Between the black stands of the trees he occasionally glimpsed a pale beast glimmering in the twilight, and a shape like one of the Eldar riding upon its back; Elwë told him that this was Oromë, a kindly and powerful being who watched over them.

His father said they should respect Oromë and not trouble him, while his mother feared dealings with any creature that came from the outside. “Other riders have come,” Mála reminded them, “dark riders, and those who have gone to them have never been seen again.”

At this, Elwë shook his head and said that was not Oromë’s doing. “I went with him once, me and Finwë and Ingwë,” he said as he and Nowë lounged on the shore, just beyond reach of the water. “He asked us to ride with him, and took us up on the back of his great beast that he calls Nahar. At great speed we traveled and went to a faraway place called Valinor. It is a place of beauty such as you have never seen.”

Nowë laughed. “You are telling tales again, cousin.”

“Nay, I speak in truth. Hear me out. In Valinor, there were people, not quite like us, but tall and beautiful like Oromë; they call themselves Valar.”

Still laughing, Nowë lay back in the sand and pillowed his head on his arms. Stars spangled the sky above, bathing the shore in a silver glow. “Yes, I am listening, cousin.”

“Ai, you are mocking me, but Oromë you have seen. Others there are, and they have been watching over us since our parents first woke by the waters. They want us to live with them in Valinor, where there are no threats or shadows.”

“They want us to leave Cuiviénen?”

But that was not a new idea, nor was the rumor of a distant, shining land. Golden-haired Ingwë had already gone, and with him went nearly two dozen Eldar that were entranced by his tales of Valinor. Finwë, too, had gone, with a larger group, and Nowë could see his cousin was restless, wanting to join them.

“Will you go?” asked Nowë. His inner eyes sought Elwë’s face and read something there he did not understand. He will go, but never again will he lay eyes upon Valinor. Something else he shall find along the way, and it will be greater still than the wonders of which he speaks.

Nowë pursed his lips and did not speak. Many of the things he saw had already come to pass; though he had been but very small at the time, he had seen his cousins with Oromë before they ever went, and had no fear when for days others sought in vain for them. But of these things he said nothing, sensing somehow this was a gift others did not have, and that it should not be flaunted openly.

Elwë looked pensive. “Cuiviénen is a beautiful place, cousin, but you have not seen Valinor. We would be safe there. There are woods and meadows and streams where we could walk without fear of shadows. And the Trees, I have not the words to describe the Two Trees that give light to that blessed land. And—oh, I have not told you this, or anyone else—but there is a great water, greater even than the pool of Cuiviénen; I glimpsed it from Nahar’s back. It is called gaiar, the Sea, and it is deep and green and full of living things. Olwë desires very much to see it, and perhaps you should like to see it, too.”

Gaiar. Nowë felt a curious longing stir within him. He had heard of the longing male and female Eldar felt when they desired to bind themselves to each other. Perhaps this was the same: the need to see, to taste and to touch. Gaiar. He said it to himself, caressing the edges of the word like a lover’s name, and then pressed his cousin to tell him all he knew, which was frustratingly little.

“You are as bad as Olwë with your questions,” laughed Elwë. “I saw but little of the Sea, but there are many bright spirits that live within its depths and make music upon strange instruments—”

“Now I know you are telling tales. If you did not see much, then how could you possibly describe such things to me?”

Elwë gave him a playful shove. “Oromë told me, when I asked. More still would I have asked, but Ingwë would scarcely let anyone else speak, so many questions did he have. Finwë was ready to gag him, and by the end of it even the Valar looked weary.”

It had ever been Ingwë’s method to have his say by silencing everyone else with his own incessant prating; many joked that Cuiviénen was a much quieter place now that he was gone.

“You are tempting me with such tales to get me to go with you,” said Nowë.

“Is it so wrong to want you to come with me?”

“Nay, but you know I cannot resist such talk.” His gaze swept along the shore toward the huts where his parents waited for him. Seldom did they go abroad now, when in the days of their awakening they had, they said, fared far and wide in their wonder. They came now only as far as the water’s edge, and only in the safety of numbers. “I do not know that my mother and father would go.”

“It is not safe for them to remain,” said Elwë.

“They will say it is safer to stay than take a strange path to an unknown place. I heard them say as much when Finwë left. They are afraid.”

“Oromë will ride with us. He did as much for Ingwë and his folk, and Finwë’s, and has sometimes brought back tidings of them. Ingwë is nigh already to Valinor, so swiftly has he pressed his followers. Did you not know?”

Nowë shoved him with a little growl of frustration, for this was the first he had heard of it. “How could I know when you hold your tongue so? When were you going to share your secret with the rest of us?”

“Who says I have kept it all to myself?” Elwë affectionately shoved him back. “There are those that know. It is only that your family likes not such talk.”

“Then you will not come with me? Olwë is coming, and there are others.”

The vision of a long shore, pale sand stretching away under a starless sky tinted with many colors, of water crashing toward him in white-plumed folds, suddenly took hold of his inner eye and moved him. Glimmerings of such a place, the imagined sound of inrushing waves, had come to him before, but always in snatches, like dreams that dissipated upon the moment of waking. Now he saw it clearly, and it was his heart’s desire.

Yes, my path will take me to that far-off place whether by following Elwë’s steps or no, he thought, and there is neither fear nor shadow in that water. “I did not say that, Elwë. You know I would come, but there are others to whom you must speak first.”

Notes:

The name Nowë comes from Tolkien himself. In “Last Writings,” Christopher Tolkien states that “Pengolod alone mentions a tradition among the Sindar of Doriath that [Círdan’s name] was in archaic form Nowë, the original meaning of which was uncertain.”

Tolkien does not say whether Círdan was born at Cuiviénen or during the journey to Beleriand. The popular belief seems to be that he was born at Cuiviénen, though he would almost certainly have not belonged to the first generation. For the purposes of the story, he belongs to the second.

Shadow-shapes: In The Silmarillion, Chapter III, it is said that the most ancient of Elven songs “tell of the shadow-shapes that walked in the hills above Cuiviénen, or would pass suddenly over the stars” and that this was the doing of Melkor, who ensnared many wandering Eldar and bore them away to captivity and torment in Utumno.

Círdan is said to be a kinsman of both Elwë (Elu Thingol) and Olwë of Alqualondë; this would also make him a relation of Celeborn.

Círdan’s gift of foresight is mentioned in both The Silmarillion and in the short essay about him in “Lost Writings,” The People of Middle Earth.

gaiar: (Telerin) the Sea.

Home Part Two

Part Two

Part Two

Part Two