A Capetown Finale

Saturday, August 12 |

| Yesterday I spent the morning interviewing a woman named Mandissa St. Clair whom I met the previous day when she picked me up at the airport. She offers tours of the black townships and has an office here at Heritage Square where she supplements her income with occasional driving for the hotel. She of course wanted to suggest that perhaps I wanted a tour of the townships, but when I explained all that I had seen and done, it seemed we had more to share just talking. I told her about my friend Sindiwe and suggested she recommend her books to tourists whom she takes to Guguletu. Yes, she said, a good idea, indeed many people had told her she should write a book. She had been born into a black family in the Eastern Cape, but when her mother left her father, she decided to get the family reclassified as colored because there were many more opportunities and privileges for colored families under apartheid. |

| It sounded like a great story, so rather than going on a tour, we met yesterday in her office with the promise that she would talk to me, I would film the story and give her a copy, and that would be the first step towards her book. |

| How did one go about getting reclassified from black to colored? Well, there actually was a pencil test. |

| At Poly Prep, a former head of middle school used to have a pencil test as part of his admissions interview. When meeting with an eleven or twelve-year-old, at some point during the interview he would "accidentally" drop a pencil on the floor and see if the boy (Poly was all-boy then) would instinctively reach to help pick it up. If he did, he passed the "pencil test." |

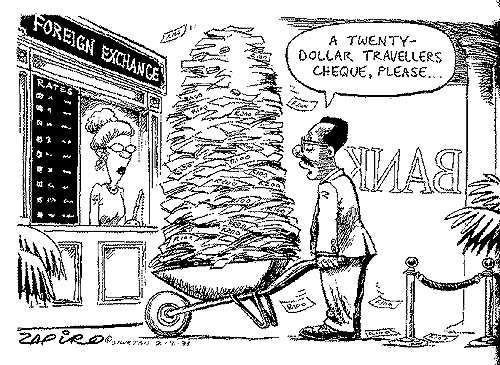

| The pencil test in South Africa was to determine how straight your hair was. It was used to distinguish blacks from coloreds. The examiner would put a pencil in your hair and have you tilt your head forward. If the pencil stayed in you were black, if it fell out, you were colored. A second test was your ability to speak Afrikaans -- coloreds typically do, and blacks don't. The key was whether you could pronounce "88" correctly, -- the equivalent of asking a European learning English to pronounce "thither." |

| How, I asked, could you convince them that you were colored when you were living in Guguletu, a black township? Oh, she said, you can't use that address, we never use that address. Even now my mother has an address in Sea Point -- the mail service is better there, and it doesn't get opened on the way. No one uses real addresses or real names. |

| Mandissa doesn't live in Guguletu any more, she lives in a formerly colored community called Heideveldt, and her youngest son, who is still in high school goes to the formerly all-white high school in Pinelands. It is an example of the upward mobility all around here. Her husband has a similar story. His father was very light, the result of his mother being raped. To make the family fit in better in the all-black Eastern Cape, he married a dark woman, hoping to have dark children who would not be teased as he had been. Most of them were, but one son Ronald, was also light, and rather than have him suffer in the same way, they sent him to Capetown to live in Guguletu with another mixed family. In that context he, too, could have himself reclassified, and it was that common bond that brought him and Mandissa together. |

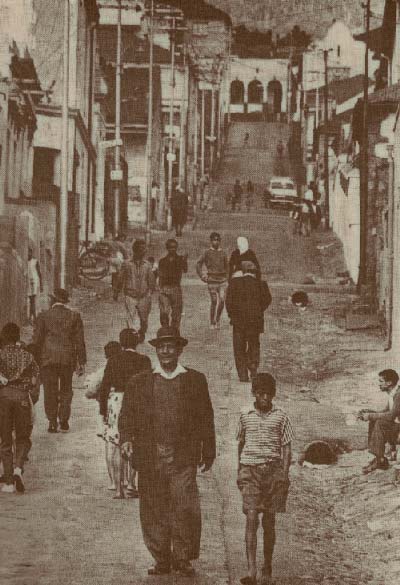

| Yesterday afternoon I went to the District 6 Museum, which is tied closely to the Guguletu story. District 6 was a part of Capetown which had a vibrant, mixed population at the time Apartheid was created -- you might think of it as the Lower East Side, with black, colored, Asian and white, especially Jews, living together in the more dilapidated buildings of Capetown. In the 1960s, after the group areas act was passed, District 6 was declared a whites only area, all the blacks, coloreds and Asians were forced to move and the area was bulldozed in as a sort of urban renewal project. |

|

| Families were resettled in places like Guguletu, which had tiny 4-room tract houses, every one the same. Of course no effort was made to settle neighbors together, and the Asians and coloreds were resettled into their own districts. Part of District 6 was used to build a community college (called a Technikon), but most of the rest of the land has lain vacant, even though it is in walking distance from the heart of downtown. Now plans are underway to allow those families who had been in district 6 to move back, although they will not get their exact old spots if that land was used for the college. |

|

| The District 6 Museum is a community affair, with a large map on the floor. People are encouraged to come in and to identify themselves and the buildings where they used to live. Both oral history and the collection of artifacts is on-going. It is another part of the essential re-writing of South African History. One white man who was assigned to assist with the bulldozing of the houses after all the people had gone, made the private decision to take down and keep the enamel street signs. He stored them in his basement and they are now a prominent and highly emotional part of the display. |

District Six circa 1962

|

| From the museum I headed back across town, buying some souvenirs finally from some of the hawkers on the pedestrian mall. I bought a tablecloth from a man from Kenya. Why, I asked him, are so many of the hawkers on the mall from other countries? I can tell you a number of people have answered this question by telling me the blacks are lazy, but he was far more insightful. "You see madam, they have been oppressed. They do not understand what they can do for themselves, and we must teach them. This is my assistant," he said, pointing to a shy young woman who would not look me in the eye, "I am teaching her how to sell." Finally at this, she smiled at me, and I smiled back. |

|

| My own bargaining of the afternoon took place in a shop of historic prints. There were a lot I could have liked, but I settled on a bin of images of the Zulu War, which got considerably more attention in the British press (they fought it) than in American papers of the time like Harpers Weekly. Each page was 160 rand -- about $25. At that price I could at best buy one, and I didn't really want or need the originals, so I arranged to select ten, leave my video camera as a deposit, take them around the corner and make photocopies (15 rand) and then return all ten, for the same 160 rand. It was, we agreed, a win-win situation. |

|

| And then finally, last night. It was all I could have hoped for. I arranged a dinner at the African Cafe, an enterprise here in Heritage Square, and invited everyone I had met to dinner. In all we were ten: Santo, from Stellenbosch who had lent me her apartment in Sea Point, Nicky, with whom I had taught, and her husband Desmond, mother and friend Sue from Maitland; Mandissa, whom I had interviewed that morning and her daughter Faith, whom I met only at dinner; and Frances and Michael Roux, with whom I had stayed in Pinelands. Unfortunately Lindiwe and Sindiwe had to go to a wake and Nora and Erhardt were quite exhausted after our trip the park -- besides they will be at the second farewell, which takes place tonight at Delheim. |

|

| tBut this was the South Africa I had hoped to find, was determined to find, even if, in part I created it. It was for all a fabulous evening in which my white friends from Pinelands, Sue (who could have passed for white, but didn't bother) and Mandissa (whose mother got herself reclassified with the pencil test)-- none of whom had met before -- all discovered that they had grandchildren in the same (formerly all white) high school in Pinelands. We were offered a feast of seventeen different dishes from all parts of Africa (I questioned the authenticity of the dessert, but no matter) -- an enjoyed even more good South African wine. |

|

| Erhardt would be asking me now, "why do you have to keep talking about what color everyone is." The day will come, I say when we can be past this, but for right now, this is the story of the New South Africa. |

|