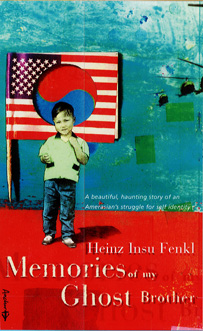

A few notes on Memories of My Ghost Brother

Heinz Insu Fenkl

Everyone who has heard me read from Memories of My Ghost Brother eventually asks me if I believe in ghosts. The question is sometimes blunt and sometimes politely round-about, and I've had to answer it in many different contexts: in classes full of students who were curious about the Japanese Colonel and Gannan, among skeptically-minded friends and colleagues who want to insist that I am creating a literary trope, among anamist Koreans of my mother's generation who find my ghosts commonplace. In trying to explain my ghosts in a common language that makes sense to everyone, I have found it useful to talk about haunting, a word and concept imbued with the idea of ghosts, but also associated with memory and emotion. We are "haunted by the ghosts of the past," "touched by the ghost of a memory," "haunted by conscience," moved by "a haunting melody." Over the years I've come to believe that literal and figurative hauntings can be the same: memories are ghosts of the past and ghosts are those memories embodied.

And both-not coincidentally-have a strong connection to place. Ghosts haunt particular places to which they have such a profound connection they cannot sever it even in death, and of course "to haunt," even for the living, is to return habitually to some meaningful spot, an "old haunt." It's this habitual quality, or perhaps, put more strongly, an involuntary habituality, a compulsion almost, that characterizes my ghosts. In Memories of My Ghost Brother, I am telling the stories of the people and the events that haunt me. I had to write my novel out of a profound need to maintain my own connection to those many people and places which no longer exist except in memory. Ghost Brother deals with the effects of the U.S. military presence in Korea, the stigma of intermarriage, the lives of prostitutes and black marketeers, the problems of Amerasian children, and the oral storytelling tradition that runs in a family and community haunted by both literal and figurative ghosts. In writing about this lost world, I was trying to compensate, somehow, for the many displacements that have marred my life and the lives of those close to me.

My mother once said that a war is the most fun you can have in life, as long as you don't get killed. During the Korean War, she didn't want to hide out in the hills with the other women of her village, so she traveled around the country dressed as a boy. Her life was full of displacements even before she married my father, who was an American soldier, and was forced to move with him every time his duty station changed. Her family didn't suffer from division by the war since her clan of Lees lived not too far from Seoul, but because she was the youngest of ten children, she was shuttled from relative to relative after her parents died and the family land was parceled out among the sons. The major displacements in her life were isolations-she had to move from Korea to Ft. Lewis, Washington, then Germany, then to various other U.S. army bases to follow my father after their marriage. She bonded with other Korean wives or-when there were no Koreans-with Japanese wives of U.S. servicemen. (It's ironic that the history of Korean-Japanese animosity gets forgotten when the women are both subordinated to their husbands in the U.S. military.)

My father's life was also a series of geographical displacements. He was born in a small town near Prague, but was then forced to move to a town in southern Germany near Munich with the other displaced Sudeten Germans. These people, who were outsiders while they were Czech, ironically became outsiders once again when they were absorbed into Germany after the annexation of the Sudetenland. My father was a Hitler Youth, and when Germany fell, he was still enrolled in a military academy which had him digging tank traps. Had he been a few years older, he might have been in one of the youthful SS units that served as Germany's last desperate line of defense against the Russians. After the end of the war, he served in the Labor Service, which was a German contingent working under the U.S. Army during the reconstruction. In 1952, he came to the U.S. and worked for the Maryknoll fathers on a dairy farm before he joined the U.S. Army and was sent to Korea where he met my mother in the late 50s. Later, he served two tours of duty in Vietnam as a specialist in counterinsurgency, then served as the sergeant of the honor guard at Panmunjom (in Korea's Demilitarized Zone) for several years. Finally, he was stationed in Germany, Texas and California before his retirement and death due to an Agent Orange-related cancer.

Untimely death, I suppose, is also a form of displacement-an early transition from this world into the next. Those close to us who make that early passage will haunt us, often in unexpected ways. As I was writing Memories of My Ghost Brother, I found the story inhabited by many such ghosts: my closest childhood friends, one who died of leukemia, the other who may have been drowned by his own mother; my uncle, who died of a stroke as he tried to hang himself; Big Uncle, who died of blood poisoning because his family decided it was wiser to spend their money on a funeral than on medicine for such an old man; my illiterate cousin who froze to death when he fell asleep drunk one winter night; my cousin, who killed herself to avert a family scandal.

As I reread the novel recently, I found, early on, a description of the landscape in which the hills recede like traditional Korean grave mounds into the distance. I suppose one could read that simile as foreshadowing all the death and tragedy to follow in the novel, or as the formation of a central theme that links the landscape with death and the land with the body. But that is actually how the hills looked around Pupyong, where I grew up. I remember how close they were when I was a child, always visible in a semicircle around the town, their scrubby trees just beginning to grow tall after the trauma of the Korean War. My father bought me a small telescope when I was in the fourth grade, and with it, I could look up into the hills and make out individual trees, even the faces of people I knew. When I returned to Pupyong fifteen years later the hills were no longer visible; the local U.S. Army base had been displaced by a large factory, and the distant landscape was lost behind a yellow-gray haze. Ten years later, in 1995, the pollution was so thick you could barely see to the end of the block. You could say the landscape itself had passed away.

But we can't let go in the face of such losses. We cannot visit the dead or return to the lost places and the lost times-we are exiled from them-and yet we are compelled to return through the act of remembering. What remains for me are the resonances of memory and nostalgia, the initially-imagined narrative, the world of my childhood over-written by the darker meanings of the world as I know it today. In the language of emotion and imagination, those are the ghosts that haunt my writing, and those are the things which I am trying to invoke with Memories of My Ghost Brother.