Song Bird

[Kê-Niao]

by Heinz Insu Fenkl

For Charlotte Church.

Long, long ago, in the mythic times before the reign of the First Emperor Chin Shi Wang Ti, there lived another emperor, a great but cruel man whose name has been forgotten. His is the tale I tell you now, before I, too, forget; because then it will be entirely lost -- forever -- and no one will know the truth and the mystery of the fate that befell him.

This emperor’s name is not known to us, for it has been destroyed from all documents and monuments, but it is rumored that his surname was Wang, and it is from his name that we get our word for king. His palace was the most wondrous in all the world, greater than all the palaces of the past and greater, by far, than any that shall ever be. It was built of white alabaster and jade of many hues, its walls inlaid with precious and semiprecious stones. It was a place of such magnificence and delicacy that a visitor was wont to hold his breath for fear of breaking something (and the penalty for breaking anything in the Emperor’s palace, as you know, was one’s life, forfeited through the most hideous torture).

In the Emperor’s garden one could see the rarest of flowers from the world’s most exotic places, and to remind the viewer of their rarity, tiny bells of transparent gold were tied to them. And when one brushed the flowers even most gently, or even walked briskly past, the bells would tinkle melodiously, their pitches matched exactly to the color and fragrance of the blossoms from which they hung. Everything in the Emperor’s garden was unique and remarkable, and it stretched so far from east to west (to match the path of the sun) that even the Imperial Gardener himself had never seen the whole of it in all his lifetime.

Those members of the Emperor’s court who were fortunate enough to have traveled to the limits of his garden knew that there was a great wood, full of tall and regal trees, that extended from there down to the sandy shore that bordered the realm of the Dragon King. In this great wood -- it was rumored -- there lived a magical bird that sang in a human voice. So beautiful was its song that the great trading ships that sailed along the coast were often distracted and ran aground in the shallows; and their rescue was invariably delayed because the local sailors would all pause, putting off their work, to listen.

Even the fishermen, who worked day and night to feed the Emperor’s court, would stop to listen; and sometimes in the evening when they sat, exhausted, to mend their nets, they would hear the song and be filled with a joy that gave them the energy to begin again the next day. “How beautiful!” they would exclaim. “How beautiful is the song of Ke-Niao!” And though they would hear the songs again and again, each time it seemed they were hearing Ke-Niao for the first time.

Envoys and ambassadors from across the world came to visit the Emperor’s great city, his palace, and the gardens. But those who had come by sea and heard Ke-Niao’s song declared it to be the most fabulous thing of all, and upon their return to their homes, they were full of her praise. And so it was that the scholars and historians and adventurers of distant lands wrote their weighty tomes in which they described what they knew of the Emperor’s realm, and all of them singled out the song of Ke-Niao as its greatest wonder. Poets waxed sentimental and nostalgic about the ethereal song of the magical bird and memoirists all expressed, as their last wish, the hope to hear that song again.

It was only a matter of time before one of these foreign books was seen by the Emperor, for he was always suspicious and wanted to know what others thought of him. Early one morning, in his pavilion that overlooked a meander of the misty River Li, the Emperor happened upon a description of his land. It pleased him to no end to read such lavish praises heaped upon his city, his palace, and his gardens. But then he found a description of something of which he knew nothing, and he turned pale. “The magical melody of Ke-Niao, the mythic songbird known to sing in the voice of a maiden, is the most wondrous thing in the whole exotic and mysterious kingdom of Cathay,” he read.

“What is this!?” shouted the Emperor. “How can there be such a thing in my empire and I not know of it?” Immediately, he flew into a rage and called together all the ministers of his High Council. And when they were gathered beneath his throne, trembling with fear, he said to them: “I have read in a foreign book that there is a magical bird in my domain. It’s song is said to be the most wondrous thing in the world, and yet I have never heard of it. Why have I never been told of it? And why is it that I, of all mortal men, have never heard it?”

“I have never heard of such a bird,” said the Chief Minister. “There has never been word of such a thing during all my time in your court, your Excellency.”

“It is my wish that the bird sing for me this evening,” said the Emperor. “If a foreign barbarian can describe this bird and know of it more intimately than I, the Emperor, then it should be easily found.”

“If such a bird exists, then I shall find it, your Excellency.”

“Indeed, you shall find it,” said the Emperor. “Or you shall face my displeasure.” And he dismissed his High Council.

Where was this magical bird to be found? The Chief Minister suddenly realized he was all alone, for all the others had fled at their first opportunity, not wanting to share his profound burden. The Chief Minister ran through the gleaming halls of the palace calling upon anyone who might listen to him, but the few souls he found to question had never heard of such a bird. So in his desperation he visited the Temple of Arcane Wisdom, where he sought out the High Zoomancer, and he demeaned himself by asking advice.

“Do not think me ignorant, for I am the Chief Minister chosen for my vast knowledge,” he said to the Zoomancer. “But I must find what seems to be a mythic bird called a Ke-Niao. Perhaps you could tell me where one is to be found nearby?”

The Zoomancer grimaced in what appeared to be pain. “Please excuse my limited knowledge, but Ke-Niao means ‘songbird,’ and the name can thus refer to any of a thousand species and their many particular permutations. Perhaps if you could tell me which particular songbird you seek, most noble Chief Minister?”

“Pah!” said the Chief Minister. And now fortified with this bit of zoological knowledge, he returned to the Emperor and told him the account must be a fiction -- invented, no doubt, by a foreign barbarian to add color to his description of their glorious empire. “Your Excellency,” he said, “the Great Sage once said one must not believe everything one sees, and even less those things seen in the pages of books.”

“The book from which I read,” hissed the Emperor, “was delivered to me by one of my best spies. It was stolen from the great library of Alexandria, where all knowledge is said to abide, and therefore it cannot be a false account.” He summarily dismissed the Chief Minister to endure a torture known as the Thousand Kowtows upon the Mat of Shards, and he announced to the others: “It is my intention to hear this Ke-Niao tonight. If she does not appear and sing for me, I shall have the lot of you pickled in brine at the end of the evening.”

“Your Excellency,” the ministers said in unison, kowtowing until their heads touched the cold, polished stone of the floor. And they dispersed to all corners of the palace, running up and down stairs from pavilion to pavilion inquiring about the mysterious bird known as Ke-Niao. Not one of them met with success, and as the day drew on the ministers began to straggle back to loiter hopelessly in the courtyard, waiting for their terrible fates.

But at last one of the ministers -- an old man beyond despair -- happened to ask the orphan boy who swept the courtyard.

“Oh, I have heard Ke-Niao,” said the boy, too simple-minded even to speak in honorifics. “In fact, I know her quite well.”

“What?” said the minister. “How is it that you can know a thing of which no one in the Emperor’s court has heard?” But the other ministers had already gathered around, and they said, “Tell us! Tell us! Is this the Ke-Niao that sings with the voice of a maiden?”

The boy was afraid now, and he cast his eyes down. “Yes, she can sing, and the most wonderful songs,” he said. “When I am done sweeping the courtyard at night, I return to the fishing village by the edge of the great wood. That is where I live. My father was lost at sea and my mother died of a broken heart waiting for his return.”

“Enough about you!” said a young minister. “We want to hear what you know of Ke-Niao.”

The boy fell to his knees in fear and mumbled apologies into the paving stones.

“Come,” said the old minister, lifting him. “Tell us about Ke-Niao as you will.”

“I am so tired when I return to the village. So tired and hungry, that I must stop halfway and rest by the edge of the wood. On the nights when Ke-Niao sings, I listen to her song and tears come to my eyes. . .” The boy sobbed and began to cry. “. . . because then I remember the lullabies my mother used to sing, and it is as if she is embracing me again.”

“Boy,” said the High Minister, “if you take us to Ke-Niao, I will post you to the imperial kitchen as a food taster, and you shall never be tired or hungry again as long as you live. Take us to her so I may invite her to sing this evening in the palace.”

So the boy led the minister to the edge of the wood where Ke-Niao sang, and the others followed behind. As the procession reached the edge of the great garden, they heard a faint chanting.

“Ah,” said a junior minister, “we have found her already! What wonderful singing -- I have certainly heard it before.”

“No, that is the chant of the Emperor’s gardeners weeding,” said the boy. “We have still a long way to go.”

After a while, when the ministers were growing tired and complained about their shoes (which were made for the paved court, and not for walking upon a trail), they heard a faint melody.

“Beautiful,” said the junior minister again. “Now I hear her. Surely that is the voice of an enchanted maiden.”

“No, that is the sound of girls singing at a village well,” said the boy. “We have still farther to go.”

Soon the ministers were all grumbling about the pains in their feet and the aches in their backs. Several of them removed their tight shoes and swooned at the sight of blisters on their delicate toes. Presently they heard a woman’s voice resounding softly among the trees, and the junior minister leapt up, declaring, “Surely, this is she! How can a mortal man resist such enchanting music?”

“No,” said the boy, “that is a woodcutter’s wife singing for her husband’s safe return.”

By now the ministers were moaning and groaning, complaining that they could walk no farther. They began to doubt the boy’s story; they sent one of their company back to fetch palanquins for their return. As they paused to rest, many of their number declaring that they could not rise again, they heard a clear melody echoing through the wood. It caused them to lift their eyes upward, to rise, to look about. In a short while even the oldest of the ministers was standing, full of energy and an unmistakable joy. The usual downward turn of their mouths had transformed into expressions of peace, and in some of them -- most incredibly -- into smiles. There was no doubt that what they all heard was the song of Ke-Niao.

“Look, there she is,” said the boy. “There,” he said, and pointed to her when the ministers looked about in confusion.

It was not a magical bird, as the ministers had expected and hoped to see. Ke-Niao was not a bird at all, but a young girl perched upon a rock in the middle of the stream, and she was washing a load of laundry as she sang.

“Can it be?” said the High Minister, “I never imagined she would be a peasant girl. Surely, she is a heavenly fairy in disguise.”

“The magical bird must have taken this form to trick us,” said a younger minister. “We must call the High Priest to capture her.”

But it was soon clear to all that the magical voice was that of the girl. “Ke-Niao,” called the boy, “the Emperor wants you to sing for him!”

“Oh, that gives me great joy,” said the girl, and she began another verse that caused the ministers to listen, dumbfounded.

“More beautiful than the sound of the golden glass bells,” said the High Minister, when he was again able to speak. “How is it we have never heard of her before? She will be a great success at court if we but change her homely appearance.”

“Shall I sing once more for you, dear Emperor?” asked Ke-Niao. So innocent was she, that she believed herself to be in his presence.

“Sweet little girl,” said the High Minister, “Do not be deceived by our regal appearance. We are to the Emperor as the stars are to the sun. I have the great pleasure of inviting you to the palace this evening, where you will gain his favor with your most excellent song.”

“But if the Emperor is like the sun, then my song is best sung for him here in the wood,” said Ke-Niao. But still, much to the relief of the ministers, she came willingly when she heard it was the Emperor’s wish.

That evening in the palace, the walls and floors of polished alabaster and marble glowed in the light of ten thousand lamps that burned only the smokeless oil of purest pine nuts. The most exquisite flowers of the Emperor’s garden, with their tiny bells of transparent gold, decorated the corridors; with all the rushing to and fro in the court, their music was so loud that one could hardly be heard to speak.

In the center of the great hall, an elegant screen had been constructed for Ke-Niao; it was made to look like a spring pavilion, and the skill of the imperial carpenters was so great that one’s eye was tricked into believing it was a real pavilion in the distance, though it was only a small imitation. Ke-Niao was to sit behind this screen before a bright lantern so that her silhouette would be cast upon the paper panels. In that way could her voice be heard without its elegance being marred by her humble appearance.

All the members of the imperial court were present, all dressed in their splendid formal gowns of embroidered silk, and the orphan boy who swept the courtyard stood by the door, for he was now an apprentice to the food taster. Every eye was turned to the small pavilion in the center of the courtyard when the Emperor nodded to the Grand Master of Court Music. A command was whispered behind the screen, the silhouette moved, and an ethereal sound suddenly filled the room. It was a voice, so sweet and yet so sad that its first notes brought tears to the Emperor’s eyes. Ke-Niao sang the Ballad of Longing for Home, her silhouette gesturing plaintively, and soon there was not a dry eye in the palace.

And then, when all were ready to bear their poignant melancholy, she sang another ballad that touched their hearts and filled them with a brilliant joy. The Emperor was so delighted that he forgot his initial displeasure (for he had hoped she would be a magical bird), and he declared that Ke-Niao should choose a jewel from among his personal treasures. “You may wear it around you neck to show that you have earned my favor,” he said, but she declined the honor with thanks.

“I have seen the Emperor’s tears,” said Ke-Niao, “and that is my richest reward, for I am told they are rarer than the rarest jewels in all of Cathay.” And then she sang again, more enchantingly than ever.

Indeed, Ke-Niao’s visit was a most resounding success. She was now to remain at court, to have her own quarters, with liberty to go out twice during the day and once during the evening. Twelve servants were appointed to attend to her every need, and they followed her everywhere as if they were bound to her by threads of silk. There was no pleasure in this confinement, no matter how regal it appeared, for Ke-Niao was not permitted to return home; her family, being lowly peasants, were barred from the palace gates.

Everyone in the capital spoke of the wondrous Ke-Niao, and when two people met, one would say “Ke” and the other would say “Niao” and they understood what was meant, for there was no other topic of conversation. Even the children of peasants were named after her, though there was little likelihood that they would ever sing a graceful note.

Then, one day, the Emperor received a large casket on which was written, “The Songbird Mechanism.”

“Here is no doubt a multi-volume account that ventures an explication of our celebrated Ke-Niao,” said the Emperor. But instead of learned books, there was a work of artifice contained in the casket, a mechanical mannequin made to look like the living Ke-Niao, but covered all over with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. Round its neck, hung a ribbon of gold foil on which was written, “From the King of Babylon, a humble gift to the Emperor of Great Cathay.”

The Emperor’s artificers followed the enclosed directions: they filled the accompanying jar with a solution of pungent rice vinegar, and then, waiting forty-five degrees on the intervals of the celestial clock, they uncoiled the two sheathed wires from the top of the jar and attached them to the two small spheres of gold on the mannequin’s base -- one yin, the other yang -- being sure that the wires did not cross. Then they called upon the real Ke-Niao, and under the Music Master’s direction, they instructed her to sing the Emperor’s favorite ballad, directing her sweet voice precisely midway between the mannequin’s upraised silver mesh palms.

And it was done. When the High Artificer pulled the red lever, the mannequin swayed its torso and its arms as if it were alive, and a sweet voice issued from its breast as if Ke-Niao herself were singing. But the mannequin could be made to sing most softly -- at a whisper for the Emperor’s sole pleasure -- or it could be made to sing so loudly that the whole palace could hear without gathering in the main courtyard; all this at the turn of a metal knob or the pull of a colored lever. The mannequin’s greatest advantage was that it could sing the same ballad again and again, in precisely the same way, without tiring or changing its inflection because of a mood or a vagary of thought. And furthermore, it was a remarkable work of art, beautiful to regard and admire, unlike the girl whose humble looks had to be hidden behind the paper screen. In a short while, the Emperor much preferred the mannequin.

“Marvelous!” exclaimed all who saw it. The envoy who had brought the mannequin was sent back with a caravan of gold and seven imperial engineers to advise the King of Babylon on the construction of his great tower.

“Surely, they must sing together,” said the members of the imperial court, “for what a duet it would make.” But they did not get on well, for Ke-Niao sang in her own way, each rendition different, though it might be the same tune, while the mannequin could only sing the same single tune again and again in exactly the same way.

“That is not a fault,” said the Master of Music. “It is quite superior, for the mannequin’s song endures and preserves the timelessness of a melody which the girl alters with each rendition.” Of course, he did not mention the fact that the mannequin’s song had been sung first by Ke-Niao. And the people did not care, for the mannequin was so much prettier to look at: it sparkled and shimmered when it moved its mechanical limbs. No one noticed that its lips did not move (or perhaps they did not point out that flaw for fear of the Emperor’s displeasure).

One hundred and forty-four times did the mannequin sing the same tune without growing tired; and the people would gladly have heard it again, but the Emperor said the living Ke-Niao should sing the song as well so that all could attest to the superiority of the mannequin.

But where was Ke-Niao? No one had noticed her when she climbed out of an open window and returned to her home at the edge of the great wood.

“What uncivil conduct,” the Emperor said when her flight had been discovered; and all the ministers of the court blamed her, saying she was a very ungrateful creature.

“But we have the better singer, after all,” said a junior minister. “What need have we for the homely girl?” And they all listened to the song again, though it was now the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth time (and even then they had not learnt it by heart, for it was a most difficult ballad).

Now the Master of Music heaped more and higher praise upon the mechanical Ke-Niao. “You must understand, your Excellency, that with a real singer we can never tell what is going to be sung, but with this machine everything is known before hand. And unlike a voice from the human apparatus, this one may be interrupted at any moment, thus allowing us to observe the fine transformations of tone within a single note. No human voice can match the elegance of the mechanism.” And the Emperor was pleased.

“Our thoughts match those exactly,” said all the minister, and then the Master of Music received permission to exhibit the mannequin to the public on the next festival day, and the Emperor commanded that they should be present to hear it sing. When they heard it they were like people intoxicated. They all praised it lavishly and kowtowed in its honor, but a poor fisherman, who had heard the real Ke-Niao, said, “It sings prettily enough, and the melodies are all alike, yet there seems something wanting. I cannot say exactly what.”

And after this, Ke-Niao was found in her village and sent to the dungeons, though the Emperor spared her the usual tortures in an unexpected gesture of mercy. The miniature pavilion behind which Ke-Niao had performed was left in one corner of the Emperor’s sleeping chamber, but the mannequin was placed on silk cushions and all the gifts of gold and jewels that Ke-Niao had received were arranged in decorative piles around it. Soon it was given the official title “Tai Ke-Niao Chi,” which means “The Great Mechanical Songbird,” and because he had decided the whole court must hear its songs each day, the Emperor had it moved to an elaborate pedestal of white jade to the left of the his throne. (That was the side from which he listened best; for common folk the left side is the side of the heart, but it is said the Emperor lacked that most human of organs.)

The Grand Master of Court Music composed a learned work about the Tai Ke-Niao Chi, which was full of the most obscure allusions to mathematics and cosmology, and yet all the court claimed to have read it and understood it for fear of annoying the Emperor. But when the Emperor himself examined the book and found it too obscure, he threw the Grand Master of Court Music into the dungeon to endure a torture called “Small Dragon Penetrates the Membrane of Sound.” Though it is said to be a painless torture, all who suffer it go mad from the unbearable itching within the brain (and they are said to have the most hideous appearance afterward, from self-inflicted gouges upon their features).

So twelve months passed, and the Emperor, his court, and all of Cathay knew every minuscule turn of the mannequin’s song; and now, for some reason, it did not please them quite so much. When the Emperor learned that the common folk in the streets could sing the ballad as well as he, a foul mood came over him and he ordered the public performances to stop at once. It was most disconcerting.

One evening, as the Tai Ke-Niao Chi was singing its song for the four-hundred-and-forty-fourth time and the Emperor lay in his bed listening, something went terribly amiss.

Something inside the mannequin snapped, and the beautiful voice suddenly ceased. What could be heard then was a rhythmic slapping which sounded, to the Emperor, like the whipping wheel used in the torture of Ten Thousand Lashes. The Emperor immediately sprang out of bed and called for his physician, but what could a physician do for a machine? They sent for the High Artificer who, after a great deal of mumbling and examination, made the mannequin sing again, but only through the workings of a crude hand crank. And one could hardly call the strange sounds that issued from the repaired Tai Ke-Niao Chi a song -- though the tune was recognizable, the words slurred and chirped and warbled like a collection of strange birds mimicking a girl’s voice.

The High Artificer explained that a vital part of the mechanism had broken from overuse, and that many other gears and wheels were worn beyond repair. The Tai Ke-Niao Chi must be used only sparingly -- and very carefully -- he said, if it was to work at all. He suggested that it be played only on special public occasions, and then he quickly retired to his quarters and took his own life, for he knew it was only a matter of time before the Emperor would find fault with him and order him to the dungeons.

Now there was great sorrow in Cathay, as the Tai Ke-Nial Chi was only allowed to play once a year; and even that was dangerous for the workings inside it. But the Emperor purged the court of all Masters of Music, and he declared that the mannequin’s song was as good as ever. No one dared contradict him.

Four years passed, and calamities came upon the land: earthquakes, floods, famine, one after the other, until finally the ominous sign of the comet appeared. Having thus lost the Mandate of Heaven, the Emperor grew sick and now he lay so ill that he was not expected to live (and secretly, it was hoped that some bold minister would put an end to him). The people clamored for news of his death so they could celebrate, but no word yet came from the inner palace.

Cold and pale the Emperor lay in his royal bed; and the whole court waited anxiously for his death, for they were eager to appoint his successor. The ministers of the High Council conferred through a day and a night and there were many plots afoot to curry favor with the successor. Indeed, the inner palace was so busy that -- under the pretext of mourning -- bolts of fine cloth had been laid down in the halls and passages so that no footstep should be heard, and all was silent and still.

But the Emperor was not yet dead, though he lay stiff and pale as alabaster on his regal bed behind camphor-scented netting of the finest silk. Outside the window the full moon rose and shone its cold light upon the Emperor’s feverish brow. His breath grew labored, and when at length he opened his eyes he saw that there was a silhouette on the screen of the small model pavilion. His eyes grew wide in surprise, for he thought it must be Ke-Niao, but it was not. It was the shadow of Lord Yama, ruler of the Kingdom of Death.

“I see out of respect for my position you have come in person and not sent your lowly emissaries,” said the Emperor.

The Lord of Death did not answer. Instead his shadow lifted the the shadow of the Emperor’s crown and put it on.

“I will not go so easily,” hissed the Emperor.

The Lord of Death raised his arms, and now, slowly intermingled with the moonbeams, shade after shade appeared, the ghosts of all the innocents the Emperor had tortured and executed. They all bore the expressions they had worn at the time of their death, and many were hideous or pathetic or pitiful to behold. A few faces were tranquil, and these scared the Emperor far more than the others.

“Do you remember us?” they asked, one after the other. “Do you remember what you did to us?” they whispered in their plaintive voices.

The Emperor clamped his eyes shut and turned his face away from them. “I remember none of you!” he cried bitterly. “Music! Music! Clang the gongs! Ring the bronze bells! Anything to drown out these voices!” But the ghosts went on and on and the shadow of Lord Yama nodded to them from behind the screen.

“Sing!” the Emperor cried to the mannequin. “Sing, you infernal machine! I’ve showered you with gold and jewels that would be the envy of princes. I’ve thrown mortals whimpering into my dungeons for you! Sing for me!”

But the mannequin was silent and still, for the foreign magic that gave it life had finally run out and no one knew how to restore it.

The Lord of Death continued to regard the Emperor with his fiery eyes, which flickered in the shadow of his face, and the room was fearfully still. Suddenly there came through the open window the sound of an ethereal voice.

It was Ke-Niao, outside in the cool moonlight, singing the seven-part ballad of Virtue and Longing. And as she sang, the ghosts grew paler and paler; the blood flowed more freely in the Emperor’s veins, returning life to his limbs. Even Lord Yama himself listened, distracted from his task, showing his pleasure with nods of his shadowy head.

At the end of the first verse, the Emperor turned his head toward her and said, “Ke-Niao, dear Ke-Niao, please do not stop now. Please, sing the next verse.”

“What have you to give me then?” she replied.

“I am on my deathbed, little girl, and my life is dearer to me than anything. I give you my imperial crown.”

So Ke-Niao sang the next verse, and the Emperor and the Lord of Death listened, and when it was done the Emperor said, “Ke-Niao, dear Ke-Niao, please do not stop now. Please, sing the next verse.”

“What have you to give me then?” she replied.

“I am on my deathbed, little girl, and my life is dearer to me than anything. I give you my imperial seal.”

And so Ke-Niao sang the next verse, and the next, and the next, and each time the Emperor gave up more of his worldly possessions. By the end of the sixth verse, he had relinquished all the territories of his vast empire, his golden sword and his grand armies, the fantastic treasures in his coffers, his ownership of ten million slaves.

As she concluded the sixth verse, the Emperor said, “Ke-Niao, dear Ke-Niao, you cannot stop now. Please, sing the final verse.”

“And what have you to give me?” asked Ke-Niao.

The Emperor was quiet for a while, and then he said, “I am on my deathbed, little girl, and my life is dearer to me than anything.” And then, in a whisper, he said, “I have nothing left to give you, dear Songbird.”

Ke-Niao bowed her head in apology. “I am sorry, my dear Emperor,” she said, “but if you have nothing left to give, then I cannot sing the final verse.”

The Emperor closed his eyes and was still. His breaths grew shallow, and under his eyelids his eyes moved as if they would roll upward in death. All was quite for the longest time, and then it was the Lord of Death who broke the silence.

“Sing,” he said, in his sonorous voice. “You cannot stop after six verses.”

“And what have you to give me, Lord Yama?” asked Ke-Niao. “What can you give me that the great Emperor could not give?”

“I give you his life,” said the Lord of Death, and there was a rumble in his throat, and his silhouette seemed to grow and engulf the room before it receded once again to be contained by the screen.

“Thank you, my lord,” said Ke-Niao, and she sang the seventh and final verse of the song. She sang of the silent tumuli where the ancients are buried, where white peonies grow among the dolmens of stone, where the mimosa trees waft their perfume on the breeze and the sweet grass is wet with dew of morning.

Then the Lord of Death longed to go and see such beauty, and he floated out through the open window in the form of a cold, white mist.

“Thank you, thank you,” said the Emperor. “Ten thousand thank-yous, little Ke-Niao. I replaced you with an mannequin and caste you into my dungeon, and yet you have returned with your song. And though I failed your test, still you saved me from death. How can I ever reward you, Ke-Niao, for I wish to give you something more, and you have left me nothing but my life.”

“You have already rewarded me more than you know,” said Ke-Niao. “You wept the first time I sang for you, and I shall never forget that, for those tears were more precious than all the great riches you gave up tonight. I could not let Lord Yama take you, dear Emperor, for how could I let you die when you have never truly lived? Now sleep and grow well again, so you may learn why life is more precious than anything.”

And as she sang again, the Emperor fell into a deep, healing sleep.

When he awoke, his fever had broken and the last beams of the setting moon shone through his window. He sat up, feeling his ch’i, his life force, restored, and he pulled down the camphored curtains and cast them across the floor. No servant had ventured into his room during the night. Only Ke-Niao was there, sitting at his bedside, barely visible; she seemed as insubstantial as the moonlight, and yet she was still softly singing.

“You must stay with me always,” said the Emperor, gently. “You may sing when it pleases you, and the tunes may be of your own choosing. I will destroy this infernal machine.”

“No,” said Ke-Niao. “Do not destroy the machine, for it did merely what was its nature. Keep it as a reminder. I cannot remain here, and I cannot linger in my village, but let me come and sing for you from time to time.”

The Emperor smiled, but his eyes remained sad.

“Do not worry, dear Emperor,” said Ke-Niao. “I return to you everything you have given me, for in giving you have reclaimed all that is yours. I will sing to you from a bough outside your window, in the evening, and sing to you so that you may be happy. I will sing to you of joys and sorrows, of those who prosper and those who suffer, of the good and the bad that are all around you. Wherever you are, I will come, and I will sing to you. But you must promise me one thing.”

In the last light of the moon, she was paler than the most regal courtesan. For an instant the Emperor marveled at how a homely peasant girl had become such a beauty, and then he knew that neither her pallor nor her beauty were of this world, for she was no longer flesh, but made of the waning light.

“Anything,” said the Emperor, and his voice cracked and tears filled his eyes. “I promise you anything, Ke-Niao -- even my life, for now that is rightfully yours and not mine.”

“I ask only that when I come to sing for you again, I will sing to a man and not an Emperor.” And with these words, Ke-Niao bowed and took her leave. When the mist cleared from the Emperor’s eyes and he could see again, the moon had set and she was gone.

It is said that when the servants came in the morning to tend to him, they found the Emperor’s bed empty. The court was in an uproar, but only briefly, because everyone had hated the man. No funeral was held, for there was no body. And when the successor took the imperial throne, things went on as if the old Emperor had never ruled. Indeed, he was so reviled that all mention of his name was stricken from the official histories.

It is also said -- and this may be mere legend -- that the Emperor had left in the night, changing into humble clothes and washing the dye from his hair. No one recognized the wizened old man who limped out of the gates of the great city and wandered into the mountains to become a hermit. They say that having lived his first life as Emperor, Wang lived his next as a mere man, and so he finally learned what it was, truly, to live as a mortal should.

A mythic Chinese telling of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Nightingale” (1844).

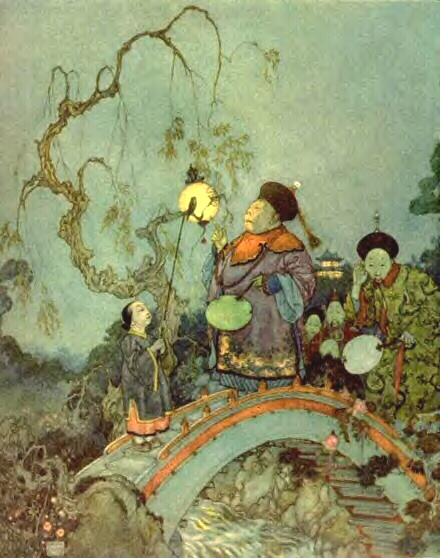

Illustration by Edmund Dulac.

This is an abridged edition of "Song Bird." The long version can be found in the journal, EnterText 3.2 http://www.brunel.ac.uk/faculty/ arts/EnterText/3_2_pdfs/fenkl.pdf.

copyright 2003 by Heinz Insu Fenkl