S U R G I C A L M E R C Y

Heinz Insu Fenkl

Illlustrations by Miram Kim

The dream comes back to me now -

desire's glass eye outside the window,

footprints tracking toward the horizon.

Smaller, smaller, black crow-tracks,

black points in the snow. Nothing.

-- Elizabeth Spires, "Snowfall"

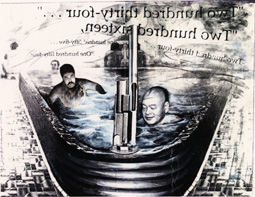

We were somewhere under Ch'ong'gyech'on, four layers down and hip-deep in black water. Rhee carried his light wand like a staff, bracing himself as if he expected a surge of current in the stillness. I could see beyond the green glow into the darkness of the periphery. I expected monsters, assassins.

"Soon," said Rhee. "He'll be here soon. When my grandfather was a child, this was a creek that ran down into the Han. There used to be a shanty town here."

"What are we waiting for, Rhee?"

"He'll be here."

There were things around us we couldn't see by the greenish light of the light wand, things I would rather not have imagined. I could feel the texture of the water -- more than wetness had seeped through the fabric of my clothes.

"My grandfather used to live here, Maurice. He said the sky was blue back then. He said the snow was white in winter. He said he visited the graves of his ancestors during the holidays. Up along the Han where there was a beach of white pebbles in the dry season."

"Come on, Rhee."

"He used to take food and soju, he said, and he did some ceremony. Some ancestor worship. Something to know the dead and keep their memory alive. That's what we're doing now, Maurice. We're honoring the dead. Keeping their memory."

In my mind, I pronounced the word -- alive -- and I saw another glow in the dark, this one bluish, tiny with distance, slowly growing with a rhythmic dripping noise. I smelled something like earth -- dirt -- no, rust -- wet rust, and I realized my nose was bleeding. "Alive," I said out loud.

Rhee waded forward, and in a moment, ripple after ripple pulsed against my hip, gentle, almost, like the pat of some maternal hand. The distant blue light grew as it approached.

"There were times when I wanted to kill her," I said.

I expected him to remark on my honesty, but Rhee only gave me an impatient look. "There is no line between love and hate," he said. "They're not clearly divided like the black and white of a yin-yang circle, Maurice. Black-and-white, gray in the distance, maybe, but not gray up close." With the Lotus T still coursing in my blood, I could suddenly see what he said floating in space in front of me like some two-color fractal design in which the colors never blended -- ever swirling into fantastic spirals -- recursive, reticulated, beautiful to look at, living and yet dead without the contrast of jealousy and devotion and sometimes we would sit by the river just to watch the light playing on the ripples of the water -- little sparkles like the flash of artillery in the distance, the white noise of wind and water like the comforting drone of distant thopper wings. In the distance . . . in the distance we watched the indios building a rope bridge across the river between two still-smoking spans of a rail bridge we had bombed during the night. It was silent. We could have heard them from where we sat, but no one spoke, and I think I heard instead, with peculiar clarity, the squeaking of twisted rope, the rasp of wood against steel, the sharp intake of labored breath. Lara looked dreamily down the bank of the river. She was smiling at them, at the irony and the beauty of it, I thought, but when I asked what she was thinking, her eyes grew cold, and she said, in an indifferent tone, "I was just thinking, Herzog." Then she turned towards me, her battle gear half undone, and I wanted to slide my hands between her shell and her flesh, to touch the comfort of her humanness, to feel the warmth of my skin on hers. She had been crying -- I noticed it suddenly, and her tears had washed away the smudges of camouflage on her cheeks, revealing the color underneath, and I realized, for the first time, that her complexion was as dark as an indio's. And even as she formed a puzzled expression, as her eyebrows arched, the rope bridge beyond her snapped -- I heard it break like a twig -- and the people tumbled down into the river and vanished without a trace. I knew then that she would leave me here the blue light had surrounded us like mist, and I could see the man standing in the small fiberglass boat. Charon, the ferryman of Hades. Eyes painted on the prow, a long bamboo pole angled into the black water.

"Igo nuguya?" said the boatman. I followed the sound of his voice into the black circle that was his mouth, half hidden under soiled gauze that wound around his face. The words hit a resonant frequency, trailing off into a distant humming echo in the blackness.

"This is the one I told you about," said Rhee.

"Kol ppajin nom, ungh?" Unnngunnngunng.

"Yes."

"Kurom olla t'agae." Aaeaeaeaeaeaeaeeee.

"Let's get on," said Rhee. "We have a ride ahead of us."

"Where we goin', Rhee? Why don't you answer him in Korean?"

"Because he understands English, and I have a fucking accent in Korean."

"What's he saying?"

"You're the poor bastard that lost his mind. Let's go, Maurice. I don't want you phasing out in the middle of things."

The boatman pushed off with his pole, and we began to move, or rather, like the scrolling of an old monitor, what I saw of the netherworld in the bluegreen glow of the two light wands began to move. I could only feel the up and down, the lateral bobbing of the boat, but no forward motion. The boatman looked down at me as he continued to speak in Korean to Rhee, a long monologue that Rhee translated as I looked out into the moving darkness.

"Tell the white guy we've been living down here for ten years. Never seeing the sunshine. They say there isn't much above ground these days anyway, so maybe we aren't missing anything.

"We came down here because we were aborted by the company. We were thrown away. Supposed to die. We left tissues up there -- enough mass for our bodies. We're dead now. DNA scans upstairs make the alarms go off, and the Keepers of Corporate Order are on the alert for any of our codes.

"That is why we are here. Ten years. Waiting. Doing our own work and minding our own lives. Three years ago one of our colleagues had an accident with a strain of Leprosy, and we were all infected. Engineered our own cure, but had to wait until now for the transplant parts and a good surgeon.

"Does the white guy know about Leprosy? The fingers fall off. Our surgeons lost their fingers, so we have to wait until they have new hands and learn how to use them before we get our own transplants. A comical situation. If the white guy is any good, then we will play exchange with him, and we will give you the potion to fix his mind."

Rhee's murmuring in English and the boatman's deep, simultaneous Korean tones mingled into an odd stereophonic babble. There was some interference pattern between the voices, a pattern taking shape between my ears, in the center of my head, between my eyes and behind my forehead in the very seat of my soul. The bones of my skull seemed to be humming in sympathy with the voices, and suddenly I saw an oddly-colored light flashing as we have just walked across the wood-and-steel bridge, listening to the water run through the sluice gate beneath us. The sound rises up, mingling with the spray into a mist that cools our ears as well as our flesh. The sweat on my brows trickles down over my eyelids, and I blink away the sting of salt. I feel suddenly uncomfortable, as if I am afraid of falling, although the bridge is low and I am not afraid of heights. Lara has a camera, and she poses me at the rail of the bridge, steps back, aims, the sun glinting on the liquid glass of the lens, and my eye, distracted, looks at the camera, at the word Pentax engraved on the alloy metal above the lens, and just as I see her smile behind the camera, her teeth flashing, I remember another Pentax from my childhood, an antique Asahi Pentax loaded with silver nitrate film, and the face behind it much smaller, a frail child's, and I hear the click of the shutter as I am blinded from one memory into another.

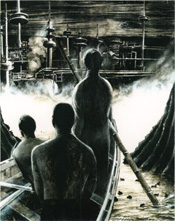

Darkness. Heat. A voice. A voice counting in the dark. I opened my eyes and thought, momentarily, that I was going blind. Everything was pale and milky, a soft-focus mist as white as the purest feathers on an egret's wing.

"One hundred two, one hundred three, one hundred four . . ."

Rhee chanted quietly as the steam rose around his head. We had finished our preliminary washing, and now it was time to bloat our skin so the scrubber man could peel us of our dead skin. I sat at the edge of the large tub, waiting for Rhee to nod his head, the signal for me to climb into the hot water and sit with him until he reached five hundred.

The scrubber man lay with his head on a small plastic bucket, snoring, waiting for us to bloat. There were two other places closer to the Yongkkum Hotel, but Rhee had brought us to this one, the Ku'unmong T'ang -- The Nine Cloud Dream Bathhouse -- because it was cheapest. We could afford a few cool drinks with the money left over.

Here, in this anachronism of a bath house, the missing white tiles looked like gaps in a sheepish smile; the bare concrete in those spots could skin you if you weren't careful sitting down. Of the eight showerheads, only two worked, and only one set of spigots had handles that wouldn't just spin aimlessly when you turned them. Poor people came here, and the water in the huge, round tub had a thin film of grayish scum floating on top. When I leaned forward and put my hand in the hot water the dirty film would jump back, leaving a tiny clear patch around my skin, repelled by the oil from my finger that dissolved in the heat of the water, but when I pulled it out again, all the dirtiness rushed back and clung to the flesh of my finger.

"One hundred fifty-four, one hundred fifty-five . . ."

The bath house manager had turned away two people with scabs on their faces, but a hunchback and a burned man had come in just behind us. "It's a camel," the scrubber man had whispered as we undressed. "See camel, ungh? And look at the nom with the boiled soup kogi all over his tari and his assu pogae." The hunchback had shuffled back and forth in an awkward dance to take his shirt off. The burned man had carefully sat on only one side of his synthetically-fleshed ass.

An old, bearded man in the far side of the tub got up and slowly rose out of the water, sighing loudly, rubbing himself around his gray pubic hair as he sat down on the edge of the tub, arranging his sagging testicles so he wouldn't sit on them.

"One hundred eighty-seven, one hundred eighty-eight . . ."

"Rhee," I said.

"Quiet. One hundred ninety-three. Ayuuu, it's hot. One hundred ninety-eight, one hundred ninety-nine . . ."

Now the bath house manager opened the door and came in to skim the dirt from the top of the hot tub with a piece of polysilk stocking he had stretched over a loop of hanger wire. He dipped the tip of his prosthetic foot into the water, watched it turn dull red, and withdrew with a grunt of dissatisfaction.

In a moment, the big faucet to my left sputtered, gushing hot water into the tub. Two other men got up, and the old man pulled his legs out. Now only three men sat in the tub with Rhee: a Mongol and two yakuza. The heat from the fresh water reached them in a moment. "Ayu ttugowo!" The Mongolian rose and waded out, the yakuza maintained their discipline, and Rhee seemed to relax even more.

"Two hundred sixteen, two hundred seventeen . . ."

I dipped my feet in just as the fresh hot water reached the spot in front of me. At first my flesh felt like it had been slapped, then the heat became unbearable, like the jab of a thousand needles, and I quickly drew my feet back out to wait that extra moment or two before going in. I wiped the water from my forehead, pushed back my wet hair, and shuffled to the shower.

"Two hundred thirty-four . . ."

I soaked myself in the cold spray, and my tiredness disappeared. I felt hard and slick like a river pebble, and the cold numbness felt like strength. I lifted one arm, then the other, and spun about several times before I turned my back to the water and breathed deeply.

"Time to come in, Maurice. Two hundred fifty-one . . ."

I climbed up to the rim of the tub and started with the very tips of my big toes, moving carefully and as slowly as possible because any sudden movement made the heat too terrible to bear. Until my knees, then thighs sank into the heat, I took deep breaths, cupping my hands around my penis and testicles and slowly touching the water. This instant was the most difficult. If I started or twitched, everything would unravel; my legs would flame and I would have to jump out and start over again. But if I was careful at this moment, the heat would become no more than an intense warmth, and I would be able to last through Rhee's final count of two hundred. I gasped as I touched the water. The heat jumped into me, filling my whole body, then receded as my buttocks and lower belly sank into the water. I continued the descent and the shallow breathing.

"Two hundred ninety-seven, two hundred ninety-eight . . ."

Now I sat on the ledge with the water up to my chin. The fever that pounded in me, behind my closed eyes, grew hotter than the water. While Rhee counted on, I matched my shallow breaths to the rhythm of his voice. Sweat and condensed steam trickled down my face and quivered ticklishly on my chin. The darkness inside my head felt as vast as the inside of the bath house. I began to think about winter, cold snowflakes falling on my hot body, melting into cool water. In the background, a cool wind blowing rhythmically through the swaying branches of a tree. My body was dissolving in the heat; everything felt identically hot and I couldn't tell what was what, or whether I was still sitting on the ledge of tile. The last bit of the cold shower's coolness disappered from the top of my head, and in my mind I saw only my head floating in a dark pool. Water, fire, clothes burning into little black flakes. I opened my eyes to the cool, bright colors of the bath house.

Each time Rhee whispered a number, the water pulsed in front of his lips and little wavelets fanned out one after the other as if the water were a living thing, counting with him. "Three hundred fifty-two, three hundred fifty-three . . ."

I wanted a drink of ice water in a clear glass cup beaded with tiny droplets. It would feel better than warmth in winter. I remembered how coldness went away so slowly; when I ran in from the winter and huddled in front of the heating vent as a child, the warmth took minutes to creep into the center of my body, but this heat seemed to begin in the very center and spread outwards, as if I were heating the water. The top of my head grew hotter and hotter, and the drops that trickled over my face felt like my melting hair.

Soon, a dizziness appeared at the back of my head just above my neck. Though my eyes were open, my vision dimmed and my spirit rose through the top of my head to hover above me in the steam, looking down at me. I felt as if I were flying through a darkness that stretched on and on, forever, and I continued to fly joyously until I knew I had gone too far to turn back. Suddenly a fear jolted my whole body, clearing the darkness. I could see that I was in the hot tub again. The sweat from my face felt cooler, and my spirit returned.

"Four hundred eighty-four, four hundred eighty-five . . ."

I sat quite still, and then, as Rhee reached five hundred, I slowly rose out of the heat into the cool, moist air.

We lay panting on the tiles until we were fully conscious again. Rhee poured three buckets of cold water over his short-cropped hair, grinning and looking at me as the water splashed past his eyes. The hunchback lay on his side under the broken showerheads, snoring softly, his hump moving rhythmically like another distended belly.

Rhee woke the scrubber man, and the man, suspended in some twilight state between sleep and waking, began to peel me. He pulled a rough cloth across my bloated skin, rubbing away curls of dead skin that looked like hundreds of tiny, black worms. As he continued to peel me, the worms grew longer and fatter until he scooped up a bucketful of hot water and washed them away. I winced and groaned in pain; the hot water on my fresh, pink skin burned with a brand new pain.

My cheek stung with the aftertaste of Rhee's slap. "Wake up, Maurice. You have to stay awake."

"Do you remember the bathhouse, Rhee?"

"Yeah, I remember."

"I knew I had a soul that day."

"Look at the light, Maurice. Keep your eyes open. We'll be there soon."

"When was it, Rhee? The bathhouse? When did you take me there?"

"That was another life. Tell me what you remember."

My vision cleared as I looked up at him. I had somehow slid down into the bottom of the boat, and I was lying with my head propped against something hard. The boatman's pole cut a diagonal through my field of vision, behind Rhee's face.

"I was afraid," I said. "I was afraid my spirit would never come back, and I was afraid I would like that better than being trapped inside myself. The old man pulled worms out of our skin, Rhee. We're already dying inside our bodies. Walking death."

"You're doing okay now."

I closed my eyes.

"Kyesok malshikyo," said the boatman.

"Open your eyes, Maurice. Talk to me."

A thump in the darkness. Thump. Someone knocking on the door. I got off the old mattress and turned the knob until the door jolted at me and Lara stood there framed in the glare of an equatorial noon. "You've been tripping." It wasn't a question. I squinted at her as she walked past me to the closet, tossed her clothes out onto the sweat soiled sheets on the bed, and started to pack. "Rhee left for Seoul-Pyongyang yesterday. He told me to give you his best," she said. "He expected you'd be out of it before this, Maurice." I sat down heavily on the green vinyl chair and groaned. Noises and movement came in with the garish sunlight through the open door, making me feel disoriented and sick. Lara opened the shades violently, one after the other, until the interior of the room looked as ugly in the light as I did. I wanted to crawl under the sheets again and wish time backwards to the moment before she had decided to make the Makarychev contacts in Santos. "Where are you going?" I said. "Back up. I can't wait here any more watching you fall apart, Maurice. We all have to decide whose side we're on sooner or later." She walked into the bathroom and came out wearing a cleansmock. Her hair was the color of sulphur, frizzed out in all directions like the holos I'd seen of dandelions in seed. Three fingers of her left hand were bandaged; in the other hand she carried a beaker full of steaming Brazilian coffee. "Marika," I said. The sound of her name shot a corroded steel spike through my spine, nailing me to the fiberpress wall of the Techie Cafe. A remarkably thin, watery blood trickled from my nose and came gouting from between my lips in long streams that puffed into the pink mist of hovercar exhaust in the distance. They carried the pilot's body away in a bag and I watched, my face over the side of the boat, as the ripples of the wake vanished into the darkness beyond the range of the light wands. I was bleeding.

"I can't keep doing this," said Rhee.

"Cham dulmyon kkushiya."

The blood dripping from my nose and mouth was as black as the water. It trickled down my chin and hung there, trembling, until it grew heavy enough to splash down and create its own tiny ripples, swallowed immediately by the wake of the boat and the swirls coiling from the boatman's pole. I dipped my hand in the water, drew a palmful up to my face and started when Rhee slapped my hand away. The sound cracked and echoed around us.

"Don't drink it, Maurice!"

"The blood. . . ."

"Don't do it, okay? We'll be there soon. You can wash, and we'll give you something to keep you awake."

"I miss her, Rhee."

"Stay awake, and you'll find her again."

"I know she's dead. Look what they did to me. I didn't even know what was going on, and look what they did to me. Do you think they let her live?"

"As far as I'm concerned, she's MIA. Until there's a body, there's hope."

"It's easier for me to believe she's dead."

"I don't believe you, Maurice."

"Yeah," I said. "I know. Even with what's left, I can't murder the memories, can I?"

The silent black water had come to life, and now a current, which I had noticed only moments before, was moving us rapidly. The boatman seemed to give one last push with the pole and then let it flop languidly in the water, only half in his grasp. I caught myself listening for the pole to beat against the boat. I expected it. I wanted it to make a sound, but it only trembled in the water, vibrating with the current, and watching it in the glow of the light wands was like watching the last flickering of a life. Fading phosphorous on an antique CRT.

We flowed more quickly with the current. I could feel the momentary acceleration push me gently backward. I tried picking out a shape a little way ahead to measure our progress, but I lost it -- or rather, it seemed to disappear -- before we got abreast. To keep my eyes so long on one thing, to keep my senses focused, seemed beyond my patience, and I resigned myself to lying quietly again, looking up into the darkness.

The boatman displayed a beautiful resignation, I thought, giving us over to the motion of water. I turned, suddenly uneasy, and argued with myself whether or not I should say something to Rhee; but before I could come to a resolution it occurred to me that my words or my silence -- anything I did -- would be futile. What did it matter what I knew or remembered? What did it matter who was still clear in my mind? I wished I could have some flash of insight that would reveal to me the essential thing, the heart of this affair that lay deep under the surface, beyond my reach and beyond my power of meddling.

"Ije koi ta wasso," said the boatman.

"Almost there, Maurice."

The stretch we entered now was narrow and straight, with high sides like a highway cut or the walls of an aqueduct. A faint light began to permeate the thick air until the light wands grew dim. The current ran smooth and swift and the banks remained eerily static. I could see living things now -- lichen, mold, or fungus, woven together by unseen rhizomes -- splayed out in mysterious patterns like stains or shadows of old petroglyphs on the stone walls. What I fought now was not sleep, but something a little unnatural, supernatural, a trance. Though I knew the boat was moving, and that the water must be making some wet noise as it was cut by the prow, I couldn't hear even the faintest sound. I wondered if I had suddenly become deaf until I heard something leap in the water with a splashing sound as loud as a pistol shot. I looked up at Rhee and saw him silhouetted against a white fog more blinding than the darkness from which we had just emerged. The fog didn't shift or dissipate; it was just there, standing all around like something solid, and then it lifted as suddenly as a shutter and I glimpsed a tower in the water, a forest of pipes and poles, an immense array of machinery all with the blazing blue-white disk of a spotlight looming over it, all perfectly still, and then the white shutter came down again, and we passed into a darkness that left everything I had seen as purple afterimages slowly fading from my vision.

We were there. We were at the place where it would happen. In a murky silence, the boatman led us onto the improvised dock that jutted like a tongue from a rectangular, black aperture in a dripping concrete wall.

Eyes and cameras watched our slow walk down a long, dimly-lit tunnel that opened up so abruptly that I suddenly stopped and teetered in place, almost losing my balance. I felt as if I were at the edge of a gigantic pit that opened downward, not upward like the vast cavern before us. This is what it must have been like for the Christians, I thought, led through the narrow mazes beneath the Coliseum and then thrust into the sudden shock of the arena to meet the lions. The cavern was so large that despite the criss-crossing floodlights, some which shone from high up, the ceiling was lost in darkness. We walked towards a quonset hut in the distance, the boatman whispering in a low voice to Rhee. His murmur and the squelching sound of our wet shoes was almost lost in the background white noise of generators and ventilation fans.

I was trembling -- no longer from the chill of my wet clothes, but from the caffein and phenylalanine mixture Rhee had injected in me to keep me awake. This new alertness had a palpable vibrational quality to it, a background noise like the barely perceptible pitch of fluorescent lights. We were sitting in the surgical theater, drinking luke-warm barley water from handle-less porcelain mugs, waiting. Rhee wore an anxious, almost grave expression, and he glanced frequently towards the long wall of vertical blinds that separated the room from the surgery. Something was bothering him, and I was slowly formulating a question to ask him when a white-haired Korean doctor entered the room through the far door.

He exchanged a formal-sounding greeting with Rhee and accepted a cup of the barley water, which Rhee poured with a near ritual grace.

"This is Dr. Lee Kim-pak," said Rhee. "We call him Dr. Samsung, because he has three surnames. He'll be the chief surgeon tomorrow, Maurice."

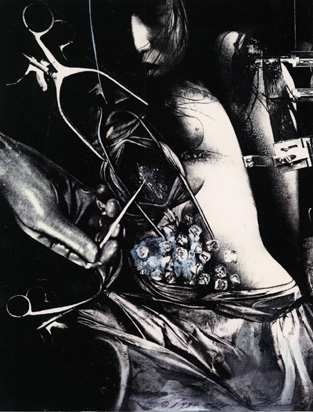

Dr. Lee shook my hand with only the very tips of his delicate fingers. I expected him to ask me questions, but instead he turned towards the operating theater and pulled on a cord. The long row of vertical blinds clacked like falling dominoes, drawing back to reveal a wall of paneled one-way glass. "Our operating room," he said.

The surgery was nearly as dim as the room we were in, but a bank of lights illuminated a group of clean-smocked doctors standing over an open bodybag full of crushed ice. A doctor moved, and through the gap he left I could see the girl, almost a woman, her naked body half obscured by the ice crystals that flashed like diamonds under the surgical floods. There was no anesthesia. The girl was wired to an EKG, and a nurse stood ready by a tray of surgical instruments as one of the doctors attached leads to silver electrodes he had inserted into various exposed parts of the girl's body.

"Are you thawing a cryo case?" I said.

"No," said Dr. Lee.

"Is she dead, then?"

"Clinically, yes." Dr. Lee sipped his barley water and turned to me. "They are going to correct an atrial septal defect. A heart problem. What do you think of our primitive facilities, Mr. Herzog? We make the best of what we have."

"Will she live?"

"Oh, almost certainly. What you see is the Meshalkin technique, perfected by a surgeon almost a century ago in Novosibirsk. We pack the body in ice to reduce the temperature to 72 degrees Farenheit. We stop the heart with potassium chloride, and then we have 90 minutes to operate before the brain begins to die."

The surgeon had finished the first incision, and now the nurse prepared the retractor for separating the ribcage. "Those electrodes are connected to accupuncture needles," said Dr. Lee. "We can monitor body functions more accurately than with the EKG alone, and in the unlikely event that the girl should regain consciousness, it also serves as anesthesia."

I could hear the ribs cracking even through the thick pane of glass that separated us from the surgery.

Dr. Lee took another sip of barley water. "When the defect is corrected, they will pour warm water over the heart, inject it with dopamine, and massage it back to life. She will then thaw out in approximately three days. Seventy-two degrees. Seventy-two hours."

"Who is she?"

Dr. Lee looked cautiously at Rhee. "It's the Emperor's daughter," said Rhee.

"I didn't know you had an emperor."

"The Emperor of Japan," said Dr. Lee. "The Japanese royal family has been in exile here since their civil war."

"I thought you hated the Japanese. Why are you helping her?"

"Ah, it's a matter of blood. Korean blood."

I remembered the stories Rhee had told me of the Japanese atrocities in Korea and Manchuria, and I thought I might have misunderstood Dr. Lee's reply. "Revenge?" I said.

Dr. Lee only laughed and waved his delicate fingers in the air.

"No, Maurice. He means the Emperor's family has Korean blood. It was a rumor for generations, but after Kim Jong-il's son smuggled the bomb into Japan and nuked Kyoto, some insiders got ahold of a blood sample from the Emperor and had the DNA sequenced. The rumor turned out to be true."

"Only a trace," said Dr. Lee. "But enough to link them to old Korean royalty. It is our privilege now to be kind to them." He finished his barley water and left us, pausing at the door to give a formal nod and say something in Korean to Rhee. He shut the door so quietly it seemed simply to become part of the wall.

Rhee watched the surgery more intently now, not bothering to be discreet as he had been in front of the doctor.

"How old is she, Rhee?"

"Sixteen, seventeen."

"You didn't bring me here to frighten me before my surgery. How long you been with her?"

"I cloned her heart, Maurice. She was brought down here for a transplant. We'd already matched her with a donor, but her old man had a thing about the purity of her royal body. Wouldn't accept it. So I had to get a cell cluster to replicate. You know what it's like to cut open a girl's chest and remove a piece of her heart?"

"You're such a fucking romantic, Rhee."

I expected him to laugh the way he might have in the past, but he looked at me serously, without a trace of conspiritorial humor. "I spent a lot of time with her. I feel like I've failed. I told her father the cloned heart would have the same congenital defect, but he wouldn't listen."

"Does he know about you?"

"He's not a happy man right now. Lost his wife and most of his entourage. His son's underground somewhere in the Hiroshima prefecture."

"I thought you would have learned from my example not to mix work and romance."

"She's bright, Maurice. Wise beyond her years. She's the one who played on the Emperor's contacts to get the fetal brain tissue for your operation."

"I'm sorry."

"After the surgery, maybe you'll remember your manners. Here, I found this for you before we left California." He handed me a holodisk case labelled "M. Herzog."

"M. Herzog? Marika?"

"It's your family album. With her belongings when I picked them up for you. Back then you said you didn't want them, but I think your mind has probably changed, ungh?"

I held the black plastic case as if it were some ancient relic, and I tried to thank him, but my voice caught.

Rhee patted me on the back. "Go and get some rest. I'm staying here to watch them close up." As I left the room, he turned to me and flashed me a rare smile. "Sweet dreams, Maurice."

Later, I was sleepless and hyperconscious, still trembling with the side-effects of the injection. In unit #17 of an anonymous cluster of quonset huts, I slotted a disk and stared for hours at holos Marika had once copied from our family album. Gunther, with his white-blond hair and blue eyes, looks a lot like Marika and my mother. In one image, my father models his new Doppler uniform and holds a chubby Gunther in his arms; my mother stands to Marika's left, resting a hand on her bony shoulder while I stand far to one side, out of effective holo range, two-dimensional, looking at them as if I were a stranger. I am the only one with dark hair. My mother had encouraged Marika and Gunther to take music lessons, but she always wanted me to do something different -- "engineering," she said, "or thinktanking." My father never hesitated to play with Gunther, but every time I asked him, in my most eager voice, he was too tired, too busy. I played alone with my mechanical thrower on the lawn.

During my rehabilitation at Diablo ORC, I had stayed away from everyone for a long time, going over my family files, taking my medication, lying there in my head while the tiny dorm module dissolved around me into vividness deeper than holography. I had wanted to remember myself, and they had told me the best way to do that was to think of meaningful people: family, friends, relations, celebrities. In the outprocessing tapes, the recovering patients were always so happy to make connections once again, to re-member their pasts, to skirt the periphery of what had been burned from their minds, to journey around the abyss like an explorer avoiding a sulfurous crater to find the promised land on the other side. The memories always made the patients so happy, and in my feeble state there was no way for me to be cynical or judgmental about what I saw. I was vulnerable then. I had remembered the bad things first. Bad things linked to the nostalgia of faces, and Marika's was on the screen now. Marika in the hospital. The room is neither cheerful nor depressing, and the background is a seascape -- popular in cancer wards -- but that makes little difference to Marika, who lies under a lattice of wires and tubes, turning the horrible jaundiced leather color of a liver casualty. She is buying time on a liver machine for as long as she can afford it, but soon a wealthier patient will outbid her and that will be the end. She coughs when she notices us. "Hello, Marika." She gives a weak smile which could have been for either of us and closes her eyes for a moment. "I've been selfish," she says. "Most of the credit's gone, Maurice. It's too late to apologize." "I don't need your credit, Marika." "Gunther made me promise to take care of you if I could, Maurice. I haven't done a very good job." Marika looks straight up into the ceiling and begins to confess all her sins to us as if we had come to perform last rites; her hollow face, ringed by her short hair, gives her the air of an ascetic, a hermit in the wilderness. Rhee looks sympathetic and embarrassed to me only because I have learned to read his lack of expression over the years. "Marika, you don't have to tell us these things," he says. "Take good care of him, Rhee. I've been a bad sister. Don't be a bad friend. If I could, I'd send you on a visit to your parents' homeland. I'm sorry." She swallows quickly, her neck twitching as if she is trying to dislodge something from her sinewy throat. "Marika," I say. She closes her eyes again. "Remember when we were little, Maurice? We had a lawn made of green grass." It goes on like this for a long time, and when we finally leave, Rhee mumbles something under his breath that sounds like the name of a drug: "Nami amitabul."

My face was wet. I realized I was remembering things I had thought inaccessible or forever lost in the inquisition. I remembered that I had left Rhee at a P-Trans dock and arranged to meet him later. I had taken a taxi back to my place, and during the flight over the filth and stink of the city, I had opaqued the partition window so the driver wouldn't see the tears on my face. I wasn't crying for Marika. I knew it was far too late for that. But could it have been the lights that pierced the interior of the cavern outside, lancing through the blackness like neural pulses through an empty skull? Or above me -- how far above -- the old avenues and boulevards, the crumbling ground routes, the vacant black districts; slums where the flickering trash fires burned, abandoned chemical dumps surrounding the free trade zones? Could it have been the great despair in me, as thick inside me as the air those spotlights pierced outside? What was I weeping for? Aboveground, before our descent into Ch'ong'gyech'on, I had found myself wondering what the ground level people were doing. I had sat with Rhee in the flying taxi, looking down through the floor port into the slum sectors. Steady fires, flashes of bright illumination, plumes of black smoke drifting northward, people walking without breathing gear on one of the ancient highway ramps. How long could they live without corporate affiliations? What percentage born with deformities or simply ejected, like an unreadable disk, from the womb? I remembered the short ground level block I had walked from our hotel to the bathhouse -- the people, the stench, the terrible cacophony, and worst of all, the texture of the air, the way it stung the lungs and eyes even through my mask and goggles. I remembered KeCorO agents sifting through the mangled remains of an organ storage warehouse, cleaning up after an attack from a Shinrudaitu cult while armored patrol craft hovered overhead. I remembered how, on the next street, a rioter shrieked as he suddenly appeared from around a corner with a six-pronged grapple protruding from his lower back. We had turned and sprinted until we were safely a block away, and from there we had watched the meat wagons come down and haul the inert rioters away, load after load into the murky sky.

And now I remembered why I was crying. Marika had died the night after our visit, while Rhee and I were drunk at a bar.

Lights. How odd to wake up to blinding lights, only to drift off again into a twilight state. I couldn't remember if I had ever fallen asleep, but now I was on the verge of dreaming again as I looked up, not squinting, into the circular bank of surgical floods, lights around a central hub like sun dogs around the sun. Somewhere up there, in silhouette, were Rhee and Dr. Lee Kim-pak, scalpels and saws ready, watching the anesthesiologist attach electrodes to the shafts of the acupuncture needles that jutted from my body. They were going to split my skull and separate the hemispheres of my brain to inject me with unformed cells from the brain of a human fetus. I heard the whine of the bone saw above me and to my right, and as its pitch suddenly changed, as the air grew momentarily sharp with the strychnine pungence of burnt bone, I suddenly remembered Yamamoto and the riddle of the three ministers. Yamamoto, slowly chewing his mouthful of prawns, asking "Which minister?" and someone's hand -- Rhee's hand -- suddenly blurring down and smashing the bone-white figurine against the edge of the walnut table. "Maurice." I turned slowly over. She was sitting at the sharp edge of the precipice, staring down into the haze over the valley. She held something small and round in her lap. "Lara, be careful." She lifted the thing from her lap and showed it to me. "I got it from a farmer who grows them secretly. Share it with me." I felt light headed as I crawled from under the red fabric of the tent and crouched at her side. The wind blew our scent up at us. Lara shivered and brushed her hair from her eyes. "Here, you try it first." "What is it?" "A peach," she said. I had never tasted anything so subtle. The texture of the skin contrasted sharply with the soft interior and the light syrup sweetness became tart towards the center. Lara took the second bite, and we alternated until she held the fantastically wrinkled, dark red pit, bare of peach tissue, in her sticky palm. "My transfer came through, Maurice. I go up to the Yucatan next week. I won't see you again till we're out." A sudden longing stabbed my heart. "I don't know what to say," I said. "I want you to stay, but I know it's safer up there." "Don't give up, Maurice." We licked each other's hands clean. She left me the damp pit as a gift, and I had nothing but a kiss to give in return.