Introduction from

Glory Fades

Away:

The Nineteenth-Century World

Series Rediscovered

by Jerry Lansche

published by Taylor Publishing Company, Dallas, Texas

The game was baseball. The nineteenth-century brand.

And what a game it was, too. The images come alive.

October 6, 1882. On a scrabbly field by the banks of the Ohio River, a bespectacled Will White sets down the fearsome Chicago White Stockings inning after inning. In this, the first post-season matchup between pennant-winning clubs of rival major leagues, White shuts out the White Stockings on eight hits...Cincinnati right fielder Harry Wheeler becomes the first goat in a series game the next day as his errant throw to third base lets in the winning run...

Two years later, Charles "Old Hoss" Radbourn becomes the first pitcher to win three games in a World Series as he utterly dominates the New York Metropolitans. Radbourn pitches every inning for the Providence Grays and gives up no earned runs, proving, as early as 1884, that good pitching stops good hitting, even in the World Series...There is Jerry Denny at third base, gloveless, fielding and perhaps even throwing with either hand...

In 1885, flashy-fielding first baseman Charlie Comiskey pounds his glove and glowers in at the hard-hitting Cap Anson, waiting his turn at the plate. Chicago center fielder George Gore, still drunk from the previous night's revelry, is replaced in center field, appropriately, by future evangelist Billy Sunday...

In 1887, Detroit Wolverines pitcher Charlie Getzien takes a no-hitter into the ninth inning of Game Six against the St. Louis Browns. The issue of who will win the game is no longer in doubt: Detroit has a 9-0 lead. At one point in the game, nineteen straight Browns are retired, so dominating is Getzien on this day. St. Louis has yet to make a safe hit as the Detroit hurler works to Arlie Latham, the leadoff batter in the ninth. Latham grounds to short and Jack Rowe kicks the ball for an error. A moment later, Bill Gleason hits a hard liner to first baseman Charlie Ganzel. Ganzel is nearly knocked off his feet, but holds onto the ball, and Latham is stranded in no-man's-land, doubled off the bag. Two outs. Tip O'Neill steps to the plate. Tip O'Neill, baseball's best hitter in 1887 with a .435 batting average. Charlie Getzien, Detroit's leading pitcher. St. Louis' best against Detroit's finest. This is the way baseball has always been, the way it will always be.

Getzien delivers.

O'Neill swings.

The ball streaks for right field, Getzien's bid for baseball immortality riding on its wings, and drops in for a single, a few feet shy of the outstretched glove of Ned Hanlon. The bid is ended The no-hitter has vanished.

There are more stories and more names. Some of the names now appear curious or quaint--Lady Baldwin, Sadie McMahon, Cupid Childs, Icebox Chamberlain, Oyster Burns, Chicken Wolf, Boileryard Clarke, and the two Cannonballs, Crane and Titcomb. And some names are those of baseball giants, men who are today enshrined in the Hall of Fame--Mike "King" Kelly, John Montgomery Ward, "Wee Willie" Keeler, John McGraw, Cy Young. But each of these men, in some way great or small, helped give the World Series the grandeur, the pomp and the luster it enjoys today. Glory fades away, but the accomplishments remain.

The game was baseball.

The nineteenth-century brand.

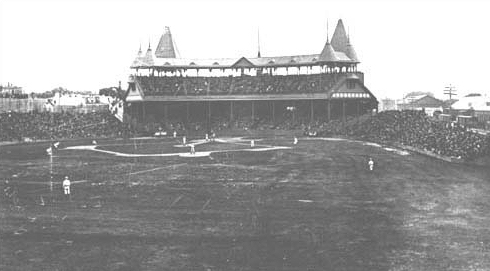

South End Grounds, Boston, late 1890s