From: Donald Shishido

Subject: Two Tales of the Internment

Date: Thu, 19 Jul 2001 0:38:27 -0700

--- Donald Shishido

--- bigdon34@earthlink.net

I have two short stories to tell about the internment of Japanese during

the war. I was just eight years old, living on the island of Maui. I was

playing in the yard with my friends when we saw a car pull up in front of

my neighbor's house. Our neighbors were the Hirai family and Mr. Hirai was

a Japanese language school principal. Two military policemen came out of

the car, went straight up to the house, knocked on the door and we could

see them talking to Mr. Hirai. About 20 minutes later, he came out with a

suitcase, got into the car with barely enough time to say goodbye to his

wife and children. The car went down the street and out of sight. We later

found out that because he had been a Japanese school principal, he was

classified as a leader and possible threat to security. He was sent to a

relocation camp, I never knew where. Ironically, this man, Mr. Hirai was so

patriotic to his adopted country, he named his sons after several American

presidents. His leaving so abruptly left his wife in much distress, having

to support five young children. I'm not sure but my father may have helped

them financially, some day I will find out. Both my parents have passed

away but my sister may know if they did help, I hope so. I do remember that

Mr. Hirai would send my father small items that he made in relocation camp

such as cigarette holders, cigar boxes and I know my father appreciated

them. The years rolled by slowly and finally the war ended in 1945 and Mr.

Hirai came home. My recollection of him was that he looked a lot older in

the five years that he had been away. Even at my young age I felt sorry

that he had been imprisoned so long and wasted years without enjoying his

young family. I joined the army and lost touch with the Hirai family till

many years later when I came back to Maui for a vacation from Los Angeles

where I worked as an aircraft illustrator. I heard the Hirai's had a little

grocery store down the street from my dad's barber shop so I walked into

the store and saw Mr Hirai sitting near the cash register and Mrs. Hirai

busily stocking shelves with canned goods. I walked up to Mr. Hirai,

said."hello, good to see you again after all these years." He just looked

at me with a blank stare and said not a word. Mrs, Hirai came over quickly

and said," I'm sorry, he won't recognize you, he's been like that for a

while." Seems the man was senile and so I left feeling sad and helpless. I

later learned that he passed away shortly after my visit. My hope is that

he was not too dissapointed at his adopted country for making the mistake

that he would or could ever be disloyal. My second story is about my friend

George Uyeno. I met George through a newspaper ad

that he placed in the Japanese language paper Rafu Shimpo published in

Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. The ad wanted members for a new collectors club

for Japanese Samurai swords. I had just started to collect and went to

join. George was a older man, about 65 at that time. He also was the

secretary, collecting dues and scheduling the semi-monthly meetings held at

a Buddhist church in Little Tokyo off First Street. We became fast friends,

he was a very sociable and likeable person, always ready to do any favors

without hesitation. He was one the the many thousands who were interned in

the relocation camps but I never heard him relate stories about his time

spent there nor did he once complain about what had to have been a very

degrading experience. One morning, we had breakfast in Little Tokyo and

over coffee talked about episodes in our lives. Most of my stories were

about my three years serving with the Army in Japan from 1955 to 1958. I

wanted to hear about his wartime experiences and relocation camp and after

much prodding, he told me an episode that illustrates the injustices that

many Japanese-American farmers and businesses experienced. George was 17

years old and was helping his older brother who owned a large farm in the

Imperial Valley. This farmland was well recognized as about the richest

crop growing soil in all America and was converted from swampland by

Japanese-American farmers. They drained off the water and made what was

considered "junk land" a modern day Garden of Eden. This made many white

farmers envious and they secretly coveted all of Imperial Valley but the

problem was, most of this land was being farmed by Japanese. When the war

started, George's brother was given notice that he had 24 hours to vacate

his land and that he and George were to be taken by train to relocation

camp somewhere in the Southwest. George's brother gathered all his

equipment, the tractors, trucks and locked them up in the barns. Locked up

his farmhouse with the furniture inside. He then asked his neighbor, a

white farmer who owned the farm next to his, to please watch over his

property till he was able to return. He also gave this farmer a tractor, a

truck and other valuable equipment as payment for looking after his farm.

George and his brother spent four years in internment camp and he told me

what kept their spirits and hopes up was the dream of going back to their

farm and resuming their planting. Sadly, there is no happy ending here.

When the brothers went back to their farm, they were shocked to find the

white farmer has confiscated their land by claiming squatter's rights. The

fact that they had been in internment camp so couldn't work the land didn't

seem to matter. George told me his brother never regained his land and had

to wait years before he could save enough money to buy another farm. Sadly,

it was not in Imperial Valley, land there was much too expensive by then.

My friend George passed away a short time ago, I hope he is back there

working on the old farm in the Imperial Valley with his brother. Goodbye

George, you were a true friend.

I hope these two stories will help non-Japanese and also the younger

Japanese-American youths realize the hardships suffered by those who were

interned during the war and how courageous they were. Yours truly, Donald

C. Shishido, Pearl City, Hawaii July 18, 2000

From: Donald Shishido

Subject: Re: The Story of the Cabbage King

Date: Mon, 24 Jul 2000 0:42:5 -1000

--- Donald Shishido

--- bigdon34@earthlink.net

Thanks for responding to my message about people I have known that

experienced the internment camps. I worked in Los Angeles as an aircraft

illustrator and have the honor of illustrating the first parts and

maintenance catalogs for both the Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet and the world's

largest plane, the C-5A the huge Army Transport. Here is my story.

I worked with a nisei born in California named Tetsuo "Tets" Kuwahara. He

was short, energetic and a real rascal who loved to tell colorful stories

about his exploits golfing and his winnings at Las Vegas. A group of us

would go to beer bars after work on Fridays and this is the story he told

me one evening after a few drinks. His father had immigrated to California

before the war and wanted to farm as he did as a young man in Japan. In his

birthplace of Kumamoto prefecture his family owned a large tract of land

encompassing several mountains with valuable trees suitable for logging.

After Japan lost the war, General MacArthur's land reform edict took away

lands from landlords and gave them to the farmers who were tenants. Many

ancestral lands were unjustly taken away and this is what happened to the

Kuwahara's.

Mr.Kuwahara was one of the original group of Japanese farmers who saw the

possibilty of turning undesirable swamp land in the Imperial Valley into

what it is today, one of the richest farming areas in America. They came up

with an ingenious way to drain the water from the swampland. Mr Kuwahara

planted cabbages and was so successful that he was known in Imperial Valley

as "The Cabbage King." When the war started he along with his young family

was ordered to leave for an internment camp and were temporarily housed at

the Tanforan Horse Racing Track in stalls that were used for horses. After

a week, they went on to the internment camp in Arizona. After the war, he

returned to the Imperial Valley and after several years had once again

regained the title of "the Cabbage King." He then went back to Japan for

the purpose of buying back the ancestral lands they had lost due to the

land reform act. He did buy all the land back and also all the mountain

land with the valuable trees. Mr.Kuwahara became a wealthy man , despite

unjustly losing land in both America and Japan and having to buy them back.

I'm sure there are stories similar to this but I think this is one of the

most inspirational. Yours truly, Donald Shshido, Pearl City, Hawaii July

23, 2000

From: Donald Shishido

Subject: Growing Up in Hawaii During the War Years

Date: Mon, 9 Oct 2000 21:57:3 -1000

--- Donald Shishido

--- bigdon34@earthlink.net

--- EarthLink: It's your Internet.

The year was 1941 and I was an 8 year old Japanese-American boy in the

little town of Paia on the island of Maui, Hawaiian Islands. A couple

friends and I were sitting around in my parent's candy shop relishing the

Baby Ruth and Big Hunk candies my mom had given us for behaving ourselves.

We heard the sound of airplanes flying overhead and thought it odd that

they were flying so low. We ran outside and saw a squadron of planes

passing overhead, close enough to see the red "meatball" painted on the

fuselage. The planes were out of sight in a few minutes and we all wondered

where those planes came from, they were clearly Japanese.

Soon after, my father came rushing into the store and told my mother "those

were Japanese planes, the radio said Pearl Harbor was under attack." My

parents closed the store and went back to the house to listen to the radio

reports. The news was just terrible and we all had a sense of apprehension

for the future. After all, my father was born in Japan and had come to work

in the sugar cane fields when he was but 17 years old. He had planned to go

back to Japan after saving enough money but instead got married and stayed

on the Island of Maui. There were six children in our family and my father

also owned a barber shop besides the candy shop.

After the declaration of war by the United States, my father went through

our home and removed every item that could possibly cast suspicion on his

loyalty to America. The photo of Emperor Hirohito on the white horse, his

shotgun that was used for hunting pheasants and quail and even the European

style sword that he used for stage plays. He belonged to a small group of

local men who would get together and entertain the plantation workers and

their families with stage plays at the community center. These men would

portray soldiers of the Japanese Army as they planned to attack the enemy,

the Russians. The younger generation may not know that in 1914, the

Russians and Japanese fought in the Russo-Japanese War with the Japanese

defeating the Russians. So, at that time it was perfectly fine to stage

these shows. My father was a ham and liked to be cast as the commanding

officer, I can still see him in his dark green uniform with a bright red

band around his cap.

Naturally, there was no more such activities when the war against Japan was

declared. The sword that my father used was stored away and I came upon it

many years later, it had never been taken out since that day. I held it and

was surprised to see how small it was. To my 8 year old eyes, the sword had

seemed so large but now I could see it was more like a toy, my father

didn't have to hide it away, I'm sure no one would see it as a weapon.

Those years were very difficult for all Japanese-Americans, most of us had

never been to Japan or had little knowledge about the country but that did

not deter some of the other non-Japanese populace in Hawaii from hurling

insults at us. Several schoolmates and I had to walk home from school and

had to pass by a home

with two brothers of our age who attended a Catholic school. They were of

Portuguese descent and just deighted in waiting for us to walk in front of

their home and they would yell out "you dirty Japs" or "sneaky rats." We

would yell for them to come out from the safety of their home, "come out

here and fight, stop hiding." Of course, those cowards never took up our

challenge. One of my classmates, a Chinese-American, shocked us one day. We

were walking by his home and he did the same thing, yelled insults at us

from his window. The ironic thing is, years later when the Chinese Army

joined the North Koreans in fighting America during the Korean War, it was

the Chinese-Americans turn to be seen as the enemy.

For myself, I never ever had any notion to hurl insults at Chinese or

Koreans, I would have been justified if I did but after experiencing such

degrading insults many years before, I sympathized with their situation.

The lesson to be learned here is to have tolerance towards other races and

treat everyone as you would like to be treated. May I mention that the

Chinese-American person that insulted me at that long ago time is now a

very good friend and I'm sure we both can look back at the past with

nothing but pleasant memories even though it was a difficult time.

Yes, growing up in Hawaii during the war years was a bittersweet experience

but I got through it without any lasting scars and believe this is the

greatest country in all the world. Aloha! Donald C. Shishido, Pearl City,

Hawaii

I wish to commend you on your very informative and well presented website. My family was involved in the evacuation of the Japanese-Americans from the West Coast in 1942. Rather than being forced into a relocation camp, my grandmother, her 12 children and many grandchildren were able to move from Oakland, Los Angeles, and Lompoc to Keetley, Utah on March 29, 1942. March 29, 1942 was the last day for voluntary evacuation from Military Area No.1.

I noticed in your Timeline that March 24, 1942 was the date that Public Proclamation No. 3 was issued. This is correct, however, the travel restrictions and curfew were effective on Friday of that week (March 27) rather than on day (March 24) the proclamation was issued. This fact can be checked in the San Francisco News article "Enemy Alien Curfew Friday" that can be found at www.sfmuseum.org/hist8/intern1.html.

March 27, 1942 is the date you have for Public Proclamation No. 4 that prohibited Japanese aliens from voluntary evacuation of Military Area No.1 in your Timeline. Based on a newspaper article in the San Francisco News, dated March 26, 1942, this proclamation was issued on March 26. In the proclamation, the deadline for voluntary evacuation from Military Area No. 1 was Sunday, March 29. Beginning on March 30, no voluntary evacuation from Military Area No. 1 was allowed. The San Francisco News article containing information about Public Proclamation No. 4 can be found at www.sfmuseum.org/hist8/intern10.html (article title: "Aliens Must Go by Sunday or Army Will Freeze Them"). My WDC Form:PM-2 (Certificate - Change of Residence Notice and Travel Permit) that allowed travel out of Military Area 1 is dated March 26, 1942, the day the family found out a deadline date of March 29 had been set for voluntary evacuation. I still have my WDC Travel Permit form as a reminder of what happened in 1942.

2000/5/15

Dear sir:

I came across your HP in the related links of Uwajimaya's HP.

Uwajimaya is my friend.

I am an American born Japanese living in Japan since 1946 when I was brought to Japan by my parents

after living in camps(Pinedale & Tule Lake) for 3 and a half years.

The articles of Ms. Terry Janzen on Relocation Camp Memories are very interesting.

My home contact is yukio_t@d2.dion.ne/jp.

Regards,

Yukio Takeshita

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Fri, 26 May 2000 06:22:01 +0900

2000/5/26

Thanks for your response.

I was born at Tacoma WA in 1935. I entered camps(Pinedale & Tule Lake) when

I was 6 years old and left the States when I was 10 years old. Left the

States late December 1945 per SS General Gordon and living in Japan ever

since January 1946.

I am planning to attend the Tule Lake Pilgrimage 2000 this summer and hope

to meet somebody my age.

Best regards,

Yukio Takeshita

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Mon, 29 May 2000 04:58:15 +0900

2000/5/29

Re: Relocation camp

Dear sir:

My father was an Issei and my mother a Utah born

Nisei(Kibei). Both families

were originated from Yamaguchi-ken.

At the time I was born, my parents were running a laundry on St. Helens

ave., Tacoma, Wash.

When WW2 broke out I was in the first grade at Central school. I remember

buying war bond stamps at school once a week or a month. I went to school

till May or June 1942 and then moved to Pinedale assembly center and a

couple of months later to Tule Lake. Being the first time to ride a train,

it was fun for a child. This was the start of the 3 and a half year camp

life.

Best regards,

Y. Takeshita

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Thu, 15 Jun 2000 20:50:24 +0900

2000/6/15

Dear sirs:

Sorry for some silence.

I lived with my parents from the day of birth so there was no trouble

communicating with them in Japanese.

Fortunately or not, I used to go to nursery school(with caucasians) and

after coming home, my parents were too busy to take care of me so my daily

task was to go to a Packard dealer in the neighbor and everybody there took

care of me so I picked up my English.

On December 7, my father came home from fishing saying "Taihen da, taihen

da"(it is terrible, it is terrible) as he heard the radio news that the

Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor. Ever since, there used to be a

policeman in front of our house after sunset. Still my neighbor people used

to take me around.

Best regards,

Y.T.

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Sun, 16 Jul 2000 05:46:11 +0900

2000/7/16

There were many of Japanese families and Nikkei children in Tacoma. I have a photograph taken at April 1942 for First Grade, Class of Miss Thompson, of Tacoma Central School. Among 28 pupils of the class 6 are of Nikkei who could be nisei or sansei. Running a laundry, delivery was mostly done after office hours so the curfew should have had effect on business.I am not sure whether the police stood outside of the house all night or not. I am told by my mother that we had to sell the laundry equipment to a junk shop for next to nothing.

Regards,

Y.T.

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Tue, 8 Aug 2000 07:56:33 +0900

2000/8/8

My grandparents were immigrants from Japan to work at the big sawmill on

Bainbridge Island in early 1900s. There is a grave of my grandmother on

Bainbridge Island.

I am told that my father started the laundry in Tacoma about 1927. It was on

St. Helens Ave. and called St. Helens Hand Laundry. My mother who was born

in Utah returned to the U.S. after education in Japan in about 1933 to marry

my father. So the laundry should have been run for about 15 years. The front

was the shop and we lived in the rear part of the building. The equipment

was sold to a junk shop at next to nothing when moving to camp. After the

war, I think my father had a chance to visit the site but he did not feel

like going back there so he decided to return to Japan with us kids.

Regards,

YT

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Mon, 11 Sep 2000 22:34:25 +0900

2000/9/11

I do not know why my father decided to return to Japan after the war. It

could have been an excuse but he used to tell us he wanted to show us kids

to our step-grandmother who was gone when we reached Japan.

We had no idea when we were on the train to Pinedale but it was fun for us

kids as it was the first time to ride on a train. For kids it was fun to

have friends living in the neighbor and getting together whenever we wanted.

Regards,

YT

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Mon, 16 Oct 2000 22:18:44 +0900

2000/10/16

For my age of 6 years old, there was no way to understand political

motivations. Riding trains to the camps were fun being my first experience

and I could play with Japanese American friends more frequently as they

lived almost next door.

The only shocking event was that my father was sent to the stockade and we

were separated for a couple of months.

Regards,

YT

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Fri, 22 Dec 2000 07:35:28 +0900

2000/12/22

Dear John:

I asked my mother but she also does not know why my father was sent to

stockade. We were separated for about a month.

When the war ended, my father had a chance to visit the town we lived before

the war but the belongings left in the buddahist church were stolen and may

be he thought it was not so safe to return to the town. Anyway, he decided

to return to Japan.

The life in Japan right after the war and living as a farmer which we never

experienced was quite different to that which we were used to.

Regards,

YT

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Wed, 3 Jan 2001 06:36:46 +0900

2001/1/03

Happy New Year !!

As I mentioned repeatedly, I was only 10 years old when brought to Japan.

We kept in touch with a family who settled in the same prefecture and one

who stayed in the US. We still exchange Season's Greeting and get together

whenever I visited the US.

I also knew of another friend but both my friends returned to the US after

finishing high school in Japan.

During Korean War, I was a high school student but went to the US consular

office to register for selective service but never served.

I was registered when I was born so should have dual citizenship. Living in

Japan for a long time, I travel with a Japanese passport whenever I go

abroad.

My father was a second son of the family but could get some share of farming

land from his brother. Not being used to the primitive farming method at

that time which relied only on manpower, my father could get a job as an

interpreter so he sold it and bought a house in the city and we moved.

During the 2 years of the later part of elementary school, I think I never

wore shoes but Zouri(straw made sandals) or Geta(wooden clogs) barefoot even

in the winter.

YT

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Mon, 5 Feb 2001 10:05:33 +0900

2001/2/05

It is very cold here in Tokyo and we had snow every weekend for three times.

Last year, I attended the Tuke Lake Pilgrimage 2000 and found that many people returned to the US after once repatriated to Japan with their parents.

The way of living changed 180 degrees but I could well fit with the Japanese

life though it was not easy.

We left some belongings in the Buddhist church when being srnt to camp but I

do not think they were valuable things. As my parents sold all the laundry

equipment before being sent to camp at almost nothing, I think we did not

have much savings.

The camp life for kids was enjoyable although the food was not so good. We

were all Japanese-American so

nobody would say do not play with Japanese or so.

YT

From: "Y. Takeshita" yukio_t@d2.dion.ne.jp

Date: Fri, 9 Mar 2001 10:12:53 +0900

Dear John:

It is about time to write again.

I was told that many of the children who went to Japan returned later to the US. Fortunately or not, my parents registered me to the Japanese consular when I was borned so I had dual citizenship but many children who were brought to Japan had not been registered as Japanese so they were treated as foreigners and not given ration. Not knowing the language well and having not much to eat may have forced them to return to the US if they had some connection such as relatives.

I have never come to Japan till the end of the war which was my first and still living here.My parents did not talk much about the internment as we were busy to keep our living. Most Japanese did not know much about citizenship so even if we talked about internment here in Japan, they thought it was natural to put Japanese in camps during the war.

I am receiving inquiries from students but most seem to think that I am living in the US.

Looking forward to being in Seattle area during Memorial Day holidays.

YT

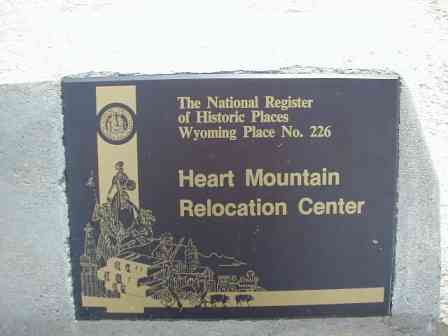

Attached are two photos. The second photo (117) is the way the camp look when it was in existence. Heart Mountain is in the back ground. Photo 107 was take approximately in the same location. There are only three buildings still standing, the power plant building, and two barracks. I will send photo of the builds with the next message.

Kurt

From: "kwebber" kwebber@tctwest.net

Subject: Re: Heart Mountain

Date: Sat, 13 May 2000 13:27:38 -0700

Photo 111 is of the power plant and 113 is of the barracks. The third barracks is to the right of this one, guess I didn't get a photo of it. The site is very poorly maintained. Both barracks have been badly vandalized.

From: "kwebber" kwebber@tctwest.net

Subject: More Photos of H.M.

Date: Sat, 13 May 2000 13:35:32 -0700

Photo 116 is of the monument plaque and 108 shows the vandalism that has taken place within the barracks. Back in about 1943 I was riding with Dad to Cody. It was at night and I saw all the lights of Heart Mountain and I asked Dad what that was and he told me. He was pretty compasionate about it. Ours is a German name and both Dad and Grandpa were concerned that they might start rounding up Germans.

When they closed Heart Mountain the Government had a big aution sale. Dad and I went. He bought some things. The one thing we still use is some knives and forks that came from the camp. I buttered my toast with one of the knives just this moring.

Kurt W. Webber

Frannie, Wyoming

I found a similar letter to my own on your web site, and I felt I should write in. I am looking for information on the camps in Arizona.

I am half Japanese. My father, Gabriel Sakuye Wada, was a year old when he was sent to a camp, and five when he left. The stories he told were scattered, but I grew up knowing my father felt uncomfortable and different around many people, and he faced many hardships of prejudice. The propaganda of World War II, which so often targetted its own citizens, left a permanent scar. After the war, his father ended up working for the railroad, and they finally ended up in Montana. My father grew up in a railroad shack. My grandfather had been a successful business owner in Los Angeles before Pearl Harbor; he lost everything and became an angry and embittered man.

Dad, in a strangely ironic and touching turn of events, became the most patriotic and loyal citizen I have ever known. He left home at eighteen, joined the Air Force, and served twenty years faithfully, without a blemish on his record. He served a tour of duty and a six month TDY in Vietnam, but struggled for promotions because of the prejudice of the older commission officers. After he retired from the millitary (not long after I was born; I am the youngest child), he became a successful businessman.

Recently, I took a class on the history of the second World War (I am a student at the University of Kansas), and wrote a paper about my father's and great-uncle's stories from the war. One of the questions that I dealt with, at the request of the professor, was "how did the war change their lives?" The answer: utterly. My father's life could have been completely different.

I lost Dad about two years ago, just as he had come to terms with everything that had happened in his life, all the events that had occurred, all the prejudice and hatred he'd had to face, and all the problems he had known. The reparations he had received allowed him to have the money to help me finish college, a dream he had held, but never been able to fulfill. It also made him feel that he had been repaid in a more esoteric sense -- his nation accepted him and was proud of him. I am saddened by the fact that he did not get to see me graduate, Bachelor of Arts with Honors.

After trying to piece together all my father's stories for the paper, I realized how many holes there are. Many of the older generation of his family is dead, and he often lost contact with a lot of his relatives, as he travelled the world when he was in the millitary. All the stories he told me indicate that he was in the Gila River Relocation Camp in Arizona. I would, however, like to find out for certain. He was too young to remember, but the stories of dust storms and, very specifically, my grandmother being terrified of "gila monsters", along with my great-uncle's specific mentions of Arizona, allowed me to piece this together. But I'd like to know for sure. If anyone knows a way to find a listing, I have my father's birth certificate, and my grandmother's full name (including maiden name).

Thanks so much,

Kimara Bernard (Wada)

I read with great interest the letters describing life in a relocation center. I was in Minidoka in 1943 and in Gila River in 1944. My father was assistant director in Minidoka and was head of agriculture in Gila River. My mother taught second grade in Gila River. I am interested in contacting anyone from Minidoka, in the hopes that I knew them when we were in camp together. I was a freshman in high school there.

Yours truly,

Marry Ann Davidson Harral

Mary Ann & Max & Eppie

On

Bethel Island, CA

Varmint@DittosRush.com

Mary Ann and Max Web Page

http://www.cctrap.com/~varmint/amaxp.htm

John, I hope you find this useful and interesting.

Frank Stoddard

8166 High Road

Hereford, AZ 85615

520-378-1977

stoddard@primenet.com

My first recollection of life was as a small boy at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Heart Mountain had been a Japanese-American Relocation Center during World War II. My early years of life were after World War II and I was not of Japanese Ancestry. My father worked for the Bureau of Reclamation in the last half of the 1940s. This government agency in essence had reclaimed Heart Mountain as a place to locate the families and their main facilities for the Powel District.

The buildings were long, narrow structures covered on the outside with black tar paper. A hall ran down the center of the buildings separating small apartments on each side. Built-up, narrow wood sidewalks attached the buildings. I especially remember the wood, for I received a splinter in my right foot, which required an operation and a stay in the hospital at Cody, which was twelve miles to the south of the camp.

Everyone, those that lived at the camp and those in town, called Heart Mountain “the Jap Camp”. I did not realize it was a derogatory reference, but those were the days when kids were playing war games and yelling ”Bombs over Tokyo”. I knew that a different kind of people had lived there before us, but I did not understand what really had taken place.

The Camp had a large, common laundry area. Many a social hour took place as the “Camp Wives” toiled over the old wringer wash machines. Next to the laundry was a huge furnace. From miles away a person could spot this facility by the tall smoke stack, the camp’s key feature. I don’t remember the smoke and I don’t know if this was used for cremation, but we all thought that the people who had lived there before had burned their dead in it. This was even confirmed in our little minds when some teenagers had placed a dummy in it scaring the entire wife’s club nearly to death and totally destroying the social hour until some men could come and fix the problem.

Down below the hill from the Camp was a magnificent garden area. The former inhabits had cultivated the land and built a ingenious system for irrigation. Every spring, for the three years that my family lived there, the garden gave me pleasant childhood memories. Ah! The excitements of seeing my first plant grow and then eating that fresh lettuce at dinner made me proud.

A half a mile (guessing on distance) north of the garden, of course, there is a sad memory. This is where Skippy, the families first dog was buried. Skippy was accidentally killed when a neighbor backed their car out of their parking spot.

My mother had a part time job, which I thoroughly enjoyed participating in. She drove a World War II surplus, black pickup. We would go down to the main highway and wait for the passenger bus to come along. When the bus stopped, the bus driver would throw the mail sack off the bus where upon my Mom picked it up and threw in the back of the pickup. We then delivered the sack to the Camp’s little store where the residence would pick up their mail.

During several waits for the bus, I remember seeing the freight train going down the track located on the far side of the highway from us. The black smoke from the steam engine would give us warning of its in pending passage. I would wave to the engineer and to the hobos who sat on top of the train. It was a thrill when they waved back, which was done every time. When I asked my mother why the men were riding on top of the train, she just said they did not have much money and they were going where they could get jobs.

Heart Mountain is where I lived when I got in my first fight, received my first kiss, had my tonsils removed, caught my first fish, and completed kindergarten. I started the first grade in Powell that was a twelve-mile school bus ride to the north. Halfway through my first grade, my father went to work for the Atomic Energy Commission, which required us to move to Idaho. Other than an occasional family reference, I never heard about Heart Mountain again until I was in College. Even then the reference to Heart Mountain was not about Japanese-American injustices, it was about how Heart Mountain was a geological wonder. I was told that it was a mountain that had slid several miles on plate tectonics as it was formed.

Many years later, I learned that my beloved Wyoming home had actually been a Japanese-American prison camp. When I lived there,” Heart” Mountain gave me images of love, like those little hearts that were on a valentine card. When I lived there, gone were the 9 guard towers, the surrounding barbed wire fencing equipped with high beam search lights, the 124 soldiers, the 3 Army Officers, and the 10,767 people kept there against their will. http://resisters.com

In 1988, the Federal Government admitted that the wartime relocation of the Japanese was unnecessary and unjust. Congress voted to pay $20,000 dollars to each internee still alive. It also declared: “On behalf of the nation, the Congress apologizes.” (McClenaghan, William A. American Government, Magruder’s. Prentice Hall, P.487)

The Congress took over forty years to admit to the injustice and erased all it errors with compensation. Executive Order No. 9006 (19 February 1941), authorizing the secretary of war to prescribe to military areas, had been determined to be a “wrong”. The wartime effort had been used as the excuse for the interments, but ironically, of the several people tried and convicted of doing harm to the United States during World War II, not one was of Japanese ancestry or decent.

Heart Mountain Internment

August 1942 – November 1944 http://scuish.scu.edu/SCU/Programs/Diversity/maps3.htm

Like anything that is unjust, lasting consequences and suffrage result. How does one compensate? What about the 63 American citizens living at Heart Mountain that were tried, convicted, and sent to prison for up to three years. All for refusing to take a draft registration physical exam? Yes, 63 American born Japanese-Americans were tried and convicted in The District Court Of The United States For The District of Wyoming on 26 June 1944. Before their conviction, they expressed their anger about the injustices done to them by formally organizing a group called the “Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee”. This group expressed their dissatisfaction to their internment by refusing to go into the military. During their trial, they stated that until their citizenship could properly be defined, they did not see it as their duty to fight and die for the country. Judge Kennedy, the presiding judge, stated “…this is without merit or legal basis…The Courts have repeatedly asserted that the orders of the boards of selective service have the substance of congressional acts and must be obeyed.” http://www.resisters.com/docs. The next day, The Wyoming Eagle announced, “63 Japs Are Given 3-Year Terms In Pen” thus, publicly stripping away any vintages of citizenship. http://www.resisters.com/docs.

These 63 criminals, regardless of Presidential pardons and Congressional apologies, were branded for life. The conflict created by their actions still carries on today. What about the members who went off to war and made the 442nd Regimental Combat Team the most decorated unit of its size in the U.S. Army during World War II? Do these people understand? Has a rift, created by an injustice, still affecting the victims today? The people that created this injustice certainly do not live with pain. Do their descendents know of the injustice? What about the mixed group of Americans that lived at Heart Mountain? Today, some of the people that went off to war still look at the protesters as cowards or less than American.

When I lived at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, I found a painted rock. Someone had painted a beautiful pastel picture of the Camp on a flat, dark rock. On a visit to my grandmother’s sod-roofed, log house near Rigby, Idaho, I presented her with my prize. Years later, after her death, when her farm was demolished, the rock was buried. This was a loss, but even sadder is the fact that Jimmy Nakayama, the first person killed from Idaho in the Vietnam War (Battle at Il Drang, Nov 1965), is buried near by. His parents were surveyors of injustice and his uncle, by the same name as Jimmy, sobbed, “Why Jimmy, it should have been me?” at the funeral. Jimmy’s uncle had fought for the “442” and his country.

Jimmy was 21 years old when an American combat plane accidentally dropped napalm on top of him. He was two days shy of his 22nd birthday and his daughter was born the day he died. The official report states “ground causality by misadventure”. http://thewall-usa.com/cgi-bin/search4.cgi

I traced my grandfathers journey through the New Mexico relocation centers

and found that there was a camp in the little town of Lordsburg, New

Mexico. It was strategic due to the proximity of I-10 and the railroad

yard. I visited the location of the camp and met the owners of the old

infirmary which is now a house. They showed me the chow hall and a shield

that the Nikkei built of an Eagle. They build it to show their loyalty to

their country that put them in that awful place. I've got a picture of

what's left over of the eagle. It's an obvious replica of an eagle taken

from a military officers cap. That's what I was doing down in New Mexico.

I'm originally from Tacoma Washington (Puyallup Valley). I became an

officer in the Air Force and was stationed in New Mexico, I became involved

with the JACL and one of their projects was to establish a memorial for the

Santa Fe Internment camp (Joe Ando is the POC for that project). While he

was leafing through the records, he happened upon my name (Haruaki

Yotsuuye) and the transfer records from an encampment called Lordsburg New

Mexico.

I know only of my grandfathers stay a Tulle Lake. Not his stay in Lordsburg

and Santa Fe.

I hope you find this interesting. It was an eye opening experience for me.

Bobby Haruaki Yotsuuye

My father Ken Sanji was interned at Jerome, Arkansas and Rohr (sp?), Arkansas. He was interned with my grandparents, his sister and two brothers (his youngest brother was born in Jerome while they were interned.) My father was 4 years old when he entered in 1941 and 8 when he was released with his family in 1945. My grandmother who passed away last year would tell us stories of the camp and we listened intently, although I didn't find out about the camps until I was a junior in high school (I'm 32 now). Our teacher instructed us to write a speech on any event that took place in U.S. history, I asked my dad what I should write about, and that's when I first found out about the camps. I was mortified, I couldn't believe that something like that could happen in this country. My teacher was so impressed with my report that I got an A+ and an apology from her for not teaching us about it in her class, she said that part of history was not supposed to be a part of the curriculum, but she was very happy that I made it a part of hers. If you would like to ask my father any questions he would be happy to respond, he enjoys being able to tell people about his and his family's experience, it's something he feels everyone should know about in order for it not to ever happen again in this country. He can be contacted at sanji1@msn.com please feel free to contact him any time. I am his daughter Christine and hope that everyone who visits your site leaves with impression that what happened during WWII was something that can never be tolerated again.

From: "joan sanji" sanji1@email.msn.com

Subject: Answers from questions re internment in Jerome, AK by Ken Sanji

Date: Mon, 23 Nov 1998 19:10:50 -0800

John, here are some of the answers to your questions regarding mine and my family's experience in the internment camps.

When you hear or read about the Jewish Holocaust in Europe it brings back memories of our experiences - no gas chambers, but the same fear and hatred, and 70,000 of it's own citizens in Concentration Camps behind barbed wire and bayonets.

After President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, on February 18, 1942, the Army arrived at our residence and were ordered to "take only what you can carry" under armed guards and placed in the back of trucks and taken to Santa Anita Race Track, which was their assembly area

We were housed, our entire family, into reconverted horse stables, we slept on army cots with straw filled mattresses, our only furniture to be had. We were retained under guard for 6 months under these conditions all the while being questioned by our Government.

After determining our status, we were placed on trains, windows covered, not knowing where we were to be shipped to. (Sounds familiar doesn't it)

We arrived at Manzanar Relocation Center for more questioning. Within a few weeks, we are again placed on guarded trains and shipped to our next camp - Jerome, Arkansas. Another Stalag Seventeen, just like the movie. After more questioning, we are again shipped further into the interior of Arkansas,

Our final stop, Rohwer, Arkansas. Stalag Seventeen's sister camp. Four armed corner towers, barbed wire fences, forty or so barracks, and the Arkansas swamps surrounding us.

The camp was divided into blocks, with a communal bathhouse and its own mess hall. The questioning stops, now boredom and fear of the unknown becomes the daily talk. Someone smuggles a crystal set into camp and we wait for news from the outside world. We are totally cut off, no information of any kind is ever told to us. We wait for the inevitable, if that's what is going to happen.

In those years it was hard being a minority, we felt the bigotry even as we arrived in Chicago.

Life was hard as a teenager, I became as bigoted as the whites who were calling me names.

In my Civics class when the subject of the Constitution came up, I stood up and told the teacher that the "Constitution" was only for the whites, and that I had just spent 3 and 1/2 years in your concentration camps! To my surprise, the teacher had never known about the camps, and was completely shocked at my statement. Of course none of my classmates knew what I was talking about either. I learned then that ignorance in this country was in part due to the fact that not everyone knew what really happened during World War II. I also realized that my own bigotry stemmed from the same ignorance. I grew up in an era of ignorance - but I've made sure through my own children that this part of history, will not be forgotten, or left out of the History books.

As I've aged I have become more mellow and I tell my story to my kids and I will tell my grandchildren when they are old enough as well. My children have learned that this can never happen again in this country, they can't afford to let it. The same bigotry still exists but the ignorance has subsided, not enough, but some progress is better than none.

Just to let you know, when they took us away to the camps, they didn't say - "when you get out, all of your things will be here waiting for you!" My father lost everything he owned. Not only was he stripped of his pride, dignity, and self respect, he lost his home, his furnishings, his car, his supermarket, and a hotel - all of it gone, never to be had again. All of it gone, just taken from him as easy as if you were taking away candy from a baby.

All that my father had heard about the US as a child growing up in Japan, the freedom, the prosperity that could be achieved, the dream - all of that was shattered - because of his slanted eyes. I don't think he ever got over what happened, and he died 5 days before the bill was signed to acknowledge the injustice. He never thought the US would apologize, he felt that way until his death. I keep the letter from the White House on my wall in a frame to acknowledge the truth, and the apology, and to also honor my father. It's a horrible fact of history, but true it is. I can only hope that what happened to the Japanese Americans in World War II is learned, and learned from it.

Sincerely,

Ken Sanji

Greetings!

Please circulate to anyone who may be interested or who may have information for me.

Thank you very much.

Best wishes,

Priscilla Wegars

KOOSKIA INTERNMENT CAMP PROJECT

735 East Sixth Street

Moscow, Idaho 83843

(208) 882-7905; e-mail: pwegars@uidaho.edu

NEWS RELEASE 26 August 1997

KOOSKIA INTERNEES AND EMPLOYEES SOUGHT

The Kooskia (pronounced KOOS-key) Internment Camp is an obscure and virtually- forgotten World War II detention facility that was located in a remote area of north-central Idaho, near Lowell. One of a number throughout the United States, administered by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), it held people of Japanese ancestry who were termed "enemy aliens," even though some of them may actually have been American citizens.

The INS camps were separate and distinct from ten major camps under War Relocation Authority (WRA) supervision. The WRA camps, including one at Minidoka, in southern Idaho, housed more than 100,000 American citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who were unconstitutionally evacuated, relocated, and interned by the U.S. government during World War II.

Approximately 175 Japanese, and some 27 Caucasian civilian employees, occupied the Kooskia Internment Camp between May 1943 and May 1945. The detainees participated in construction of the Lewis and Clark Highway, parallel to the wild and scenic Lochsa River. Known today as Highway 12, that route runs between Lewiston, Idaho and Lolo, Montana.

Researcher Priscilla Wegars urgently seeks former Kooskia Internment Camp internees and employees, or their descendants, in order to interview them. She is also eager to locate any letters, diaries, photographs, or other documents relating to the Kooskia Internment Camp experience.

Wegars recently received a grant from the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund (CLPEF) in support of this project. The CLPEF was authorized by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which awarded apologies and redress payments to citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry unconstitutionally evacuated, relocated, and interned during World War II. The Act also provided for the establishment of the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, financing endeavors that inform the public about the internment in order to prevent the recurrence of any similar event.

Wegars, the editor of Hidden Heritage: Historical Archaeology of the Overseas Chinese (Baywood, 1993), is an affiliate faculty member with the rank of assistant professor in the University of Idaho's Department of Sociology/Anthropology and is the volunteer curator of the Laboratory of Anthropology's Asian American Comparative Collection.

Contact:

Priscilla Wegars, Ph.D.

(208) 882-7905

e-mail: pwegars@uidaho.edu

REVISED AUGUST 1997---------http://www.uidaho.edu/LS/AACC/------------

Priscilla Wegars, Research Associate and Volunteer Curator, Asian American

Comparative Collection, Laboratory of Anthropology, University of Idaho,

Moscow, ID 83844-1111, 208-885-7075, e-mail, pwegars@uidaho.edu

Saturday Feb 22, '97 10;00 PM EST

Hello John: Thank you for putting up my items about the re-issuing of "Personal Justice Denied and Michi Weglyn's "Years of Infamy."

I don't know who made that tremendous contribution of "Time Line." It certainly offers a great avenue to the understanding of the events of those times. Since I have some suggestions about additions that I would be pleased to offer for the consideration of the author, how do I go about contacting that person?

For example, the Dec 11,1941 entry states that the FBI detained 1370 "'Japanese Americans." Those people were not American citizens but Japanese aliens who, because of an act by the Empire of Japan for which they could not be held responsible, and anti-Asian immigration laws, they became technically "enemy aliens." And I think it would add to that same comment by including the fact that 857 Germans and 147 Italians were also picked up by that date so that the viewer does not get the impression that only Japanese were detained. (These figures come from page 55 of "Personal Justice Denied: the Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.)

By no means do I mean to be critical in a negative sense.

Thank you for your consideration.

Jack Herzig

Jan 3, 1997 1 AM Friday

Thank you for your note of Jan 2, 4:35 PM but I was not keeping your site

"accurate" since it was already correct, but not quite complete. I hope

only to add additional material to the matter.

Similarly, please allow me to add to Professor Tetsuden Kashima's excellent

report of the shootings of

Isomura and Kobata en route to Lordsburg in

July, 1942 as you have noted your "Shootings".

I happened to find in the

National Archives in Washington the report of the

Army's local board that reviewed the event. Headed by Captain Arber (sic)

J. Warren, First Lieutenants Phillip Bond and Edward C. Strum were the

other two members.

Appearing before them were PFC Clarence A. Burleson, ASN 38132019 who fired

the shots, PFC Joseph F. Kelly, ASN 34078392, who was with Burleson at the

time of the shooting, their First Sergeant John A. Beckman, 38038827, and

!st Lieutenant Harold Stull. The board found that Burleson was justified

in killing the two Issei because they were trying to escape. The record

did not show that any of the men who knew that Isomura and Kobata were so

ill that they were unable to keep up with the rest of the prisoners were

allowed to testify.

What was particularly revealing was the picture taken of the corpses by the local coroner. The wounds were in the middle left portion of the men's backs. Since the weapon used was a shotgun, the wounds indicated that they were shot at close range. They were not at some distance when they were hit since the shot pattern would have been much wider than their wounds showed. This does not appear to have occurred to the Army board who should have known about nasty things like guns, shotguns, bullets and people.

I attempted in 1993 to locate any of the seven military personnel who were involved in this event through placing notices in veterans' magazine, stating that I was doing research at the National Archives. A wonderful fellow, Joseph J. Dove of San Francisco, saw my request and sent me lists of names and addresses of people whose names were similar to those whom I was seeking that he had gotten from a program called "Phone Disk." To them I mailed 77 post cards. Replies were interesting and all wished me luck but only one with the name of Burleson held promise since a relative wrote that he had retired from the Army in the early ''70s. I phoned him in Texas, only to find that he was in hospital and died shortly thereafter.

I hope that you find this of interest.

Jack Herzig

January 1, 1997 2 PM EST

On your 8 page project titled "Shootings" at

www.geocities/Athens/8420/shootings.html please consider the following on

Ito and Kanagawa taken from Thomas and Nishimoto's "The Spoilage" which is

listed as the source #2 at page 8:

What your viewers might not be aware of is that the authors used

pseudonyms (as mentioned in footnote 14 on their page XIV). Their "Dick

Miwa" who played the central role in the rally where the shootings took

place, was and is

Harry Ueno, the same man quoted at the end of the Togo

Tanaka's recounting the event at your page 4. Harry was the leader of the

Kitchen Workers' Union. He was responsible for confronting the camp

authorities about their staff 's stealing of meat and sugar that was meant

for the kitchens of the internees. It was his release from confinement

that the crowd was demanding on the day of the Manzanar "riot."

Harry Ueno is alive and well on this first day of 1997 in San Jose, CA.

He is a wonderful man who eagerly joined in the historic class action suit

"Hohri et al vs the United States" as a named plaintiff representing the

"Kibei" class who were held in

the Department of Justice and the War

Relocation Authority facilities.

For more details see "Manzanar Martyr, an Interview with Harry Y. Ueno by

Sue Embry, Arthur Hansen & Betty K. Mitson, c 1986, Cal State Univ at

Fullerton,CA.

Fred Tayama is identified in "Manzanar Martyr" as the person whose

pseudonym of "Frank Matsuda" was used by Thomas & Nishimoto in their

recounting of the event.

/s/Jack Herzig

Hello

My name is Oscar Gushiken, I looked through your web page and found it

to be VERY interesting. Especially about Japanese-American Internment

or Concentration Camps.

I thought you might be interested in knowing that Mexico and Canada also

had Japanese concentration camps, during WWII.

I am Mexican, half Japanese...my father was born in a concentration camp

in Mexico, during WWII.

I am conducting my own research on Japanese-Mexicans, during WWII. It

is very difficult, since the Mexican government has not officially

recognized the existance of these camps. If you come across some

information or can set me on the right track, I would greatly

appreaciate you assistance.

Sincerely

Oscar Gushiken

Gushi@mail.concentric.net

Date: Thu, 14 Dec 2000 17:30:14 -0800

From: "Jessica Hano"

what info do you have on internment camps in mexico? my grandparents, father and aunts were in a camp outside of mexico city during the war. i believe the town is called cuernavaca and the camp was used as a farm after the war. there is very little information regarding this camp and there has never been any attempt at restitution by the mexican or american govts. my father and aunt both requested aid in order to apply for restitution here in the states or in mexico but were turned away. i just wonder if there is any information out there.

Between 1942 and 1945, the JASRC assisted in relocating over 2,000 Nikkei students from camps to campuses throughout the midwest, east coast and southern states. Headquartered in Philadelphia, this volunteer organization was led by quakers and leaders within the YMCA-YWCA. It would be great to add this info to the web page!

Date: Thu, 5 Dec 1996 23:21:07 -0500

From: NAVargas@aol.com

Subject: Re: RE: Japanese American Student Relocation Council

John-

After Dewitt,Bendetsen and

Stimson convinced

Roosevelt to sign

E.O. 9066,

Asst. Sec. of War McCloy asked Clarence Pickett Exec Dir. of

the American

Friends Service committee (read: quakers) to help establish the Student

Relocation Council. The Council relocated 400 students by Fall term, 1942.

(21.5%

Kibei!) Most were placed in the Midwest and East Coast. The coucil

tried to assist with grants and scholarships, with an average of about $200

per student. the Council continued to operate until July 1946. During term

1945-1946, the Council had 2870 Nikkei in colleges and universities

throughout the U.S. If you're interested in further info, check out Robert

O'Brien, "The College Nisei" Arno Press reprint, 1978.

Al Vargas

Sunday, March 02, 1997. 00:35 a.m. EST

Dear John: Will you please consider making the following entry to your site! Thank you again.

From 1942 to 1946, in a massive abrogation of their civil and constitutional rights, thousands of Japanese-Americans were excluded from their homes and held in concentration camps. "Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress" takes a hard look at the events of that time and why they happened. It also documents the efforts of the National Council for Japanese-American Redress (NCJAR) to obtain monetary redress for the Japanese-Americans through the judicial system since the Supreme Court had, on narrow and shaky grounds, been thought to have upheld the government's actions in the Korematsu decision.

"Repairing America" is both a history and a personal account. The author, William M. Hohri, is a Japanese-American who was imprisoned with his family at the age of fifteen from 1942 to 1945, and was the chairman of NCJAR. The book contains excerpts of Hohri's testimony given at U.S. governmental hearings as well as testimony of other victims, former government officials, experts, and opponents to redress.

Illustrated with historic and recents photographs, "Repairing America" poses insightful questions and answers about this shameful period of American history. It states that only through the mighty symbolism of financial compensation to the victims and their heirs can the healing of America take place.

Orders for "Repairing American: An Account of the Movement for Japanese-American Redress," can be sent to the author: William M. Hohri, 25840 Viana Ave.,#B, Lomita, CA 90717.

------------------------------

Thank you, Mr. Yu.

By: Jack Herzig

From: "Herzig" aikojack@idsonline.com

Subject: "Personal Justice Denied" and "Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps" now available

Date: Sun, 16 Feb 1997 19:09:15 -0500

Dear John: May I request that you delete my earlier items on "Personal Justice Denied," and Michi Weglyn's "Years of Infamy" that you entered into the internet, and substitute the following updates:

"PERSONAL JUSTICE DENIED" NOW AVAILABLE

" Personal Justice Denied," the report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment (CWRIC), which was long out of print, has recently been re-published by the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund (CLPEF), of Washington. D.C. & San Francisco, and the University of Washington Press, Seattle and London. It now contains a foreword by Professor Tetsuden Kashima, of the University of Washington, and a prologue by the CLPEF board, which provide a wide perspective of what has happened in Japanese America since the report was released in December, 1982.

The CWRIC report is a masterful summary of events surrounding the wartime forced removal and subsequent detention of the entire west coast Japanese American population and is a strong indictment of government policies that led to this wholesale violation of the rights of 112,000 innocent people. The report and its recommendations were instrumental in affecting a presidential apology and token monetary restitution to the surviving victims as well as to members of the Alaskan Aleut and Pribilof Islanders..

Copies may be ordered from the University of Washington Press, PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145-5096, USA, for $16.95 plus $4.00 shipping, which may be charged to MasterCard, Visa, AmEx, or Discover. For toll free orders call 1-800-441-4115, 8 AM to 4 PM Pacific Time, Monday through Friday.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

"YEARS OF INFAMY: THE UNTOLD STORY OF AMERICA'S CONCENTRATION CAMPS" NOW AVAILABLE

An expanded 1996 edition of Michi Weglyn's acclaimed book, "Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentraton Camps," has been reissued by the University of Washington Press for worldwide distribution. With an introduction by James A. Michener, the book has been lauded by the New York Times upon its publication as "fascinating and shattering...extraordinary history." The prestigous Kirkus Review called it "certainly the most thoroughly documented account of...Japanese American internment....Behind the claim of 'military necessity,'' Weglyn points to the need for the U.S. desire for a 'barter reserve'..., i.e., hostages of war [to be exchanged for American diplomats and others caught up in the rapid Japanese expansion in early 1942]." Also included is the little known story of U.S. actions in abducting and then detaining in the U.S. over two thousand persons of Japanese ancestry from Central and South American countries.

The book can be ordered from the University of Washington Press, P.O.Box 50096, Seattle,WA 98145-5096, U.S.A., for $16.95 plus $4.00 shipping. There is a 40% discount for ten or more copies. MasterCard, Visa, AmEx, and Discover may also be used. Phone orders at 1-800-441-4115, 8 AM through 4 PM Pacific time, Monday through Friday.

Single copies and orders for less than ten may be ordered from Island Books (Seattle), 1-800-432-1640.

From: "Herzig" aikojack@idsonline.com

Subject: Personal Justice Denied Now Available

Date: Mon, 2 Dec 1996 20:38:56 -0500

Dec 2,1996 Tuesday 8:45 PM EST

Personal Justice Denied, the report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation

and Internment of Civilians (CRWRIC) , long out of print, is now available

from the University of Washington Press. It now has a foreword by

Professor Tetsuden Kashima.

A toll-free ordering line is available: 1-800-441-4115 from 8:00 AM to 4

PM Pacific time. Cost is $16,95 plus $ 4.00 shipping.

From: "Herzig" aikojack@idsonline.com

Subject: Re: Personal Justice Denied Now Available

Date: Fri, 6 Dec 1996 18:04:30 -0500

Dec 6,96 Friday 6:00 PM EST

An expanded 1996 version of Michi Weglyn's monumental work,"Years of

Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps," has been

reissued with some updated material by the University of Washington Press.

Her research resulted in what most reviewers and historians have stated as

the most significant contribution to the story of the Japanese American

exclusion and detention.

Single copies and orders for less than ten may be ordered from Island Books

1-800-432-1640 at $16.95 postpaid. Orders for ten or more are available

from the Univ of Wash Press, PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 9815-5096 (that's

what it says!) at a 40% discount. Their 800 number is 441-4115.

While on vacation in Denver I got a copy of the following from my girlfriend's aunt and thought if you didn't have it you might want it. It is the letter that was sent with the $20,000 to the survivors of the camps. Please excuse any errors in spelling or punctuation. Thanks for the web page. If you have any questions or comments I may be reached at RkentC@aol.com.

A monetary sum and words alone cannot restore lost years or erase painful memories; neither can they fully convey our Nation's resolve to rectify injustice and to uphold the rights of individuals. We can never fully right the wrongs of the past. But we can take a clear stand for justice and recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II.

In enacting a law calling for restitution and offering a sincere apology, your fellow Americans have, in a very real sense, renewed their traditional commitment to the ideals of freedom, equality, and justice. You and your family have our best wishes for the future.

Sincerely,

s/George Bush

President of the United States

October 1990

|

|

|