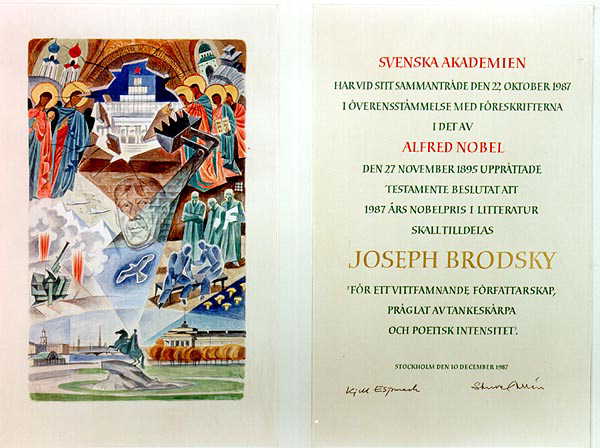

Press Release: The Nobel Prize for Literature 1987

- Swedish Academy

- The Permanent Secretary

October 1987

Joseph Brodsky

A.: You comment on the value of "estrangement"to developing first an individual perspective and second a writer's perspective. Is the one a necessary prerequisite of the other and how much are you using Shklovsky's concept of "estrangement", if at all?

"Appearances are all there is" (Less Than One). David Hockney has said "all art is surface" and that surface is "the first reality". Are you talking about the same thing and what depths are negated by privileging surface?

In Less Than One you deny the hegemony of the "linear process", yet immediately follow this with a (linear) paradigm -- "A school is a factory is a poem is a prison is academia is boredom, with flashes of panic." Again, shortly after arguing that narrative, like memory, should be non-linear (ie digressive), you assert that history is cyclic (a linear image). Would you comment firstly on the nature of these contradictions and secondly on the problematic of linearity in your writing?

"Selected Essays" is, it seems to me, self-consciously aphoristic: self-conscious in poetic rather than prosaic decision making (eg "The more indebted the artist, the richer he is."). Can you expand?

How completely do oppressive political regimes destroy individualism? I am thinking that individualism may find alternative modes of expression, that it is not something which can be cultured or suppressed but is an innate predisposition. Similarly, in a "free" society, expressions of "individualism" are often no more than a reclothed lumpen consciousness.

You glibly put Sholokov's Nobel Prize (65) down to "a huge shipbuilding order placed in Sweden" (Less Than One). How credible do you find the "All Literature Is Politics" argument?

Post-war poetry in the USSR and the USA has vast stylistic/ thematic differences. First, are you now looking to become part of the American tradition and second, how (critically) constrained do you feel in relation to American culture?

In the Preface to "A Part of Speech" you mention reworking translations of your work to bring them closer to the original in terms of content rather than form. Has this forced choice, emphasising content over form, caused you to rethink your attitude to language in any way?

How is poetry best read -- aloud to an audience or silently to oneself?

Although memory fails to adequately reconstruct the past (In "A Room and A Half") has poetry allowed any successful reconstruction?

When Publius says, "Home!...where you won't be back ever." (Marbles), is this Joseph Brodsky speaking to us directly or is it facile to draw comparisons between an author and his characters?

Your work draws on many other literary sources making for more or less esoteric writing. What is your attitude towards the accessibility of your work?

JIM LEHRER: Joseph Brodsky appeared on the NewsHour in 1988, and talked about the thing he liked most about America; its spirit of individualism.

JOSEPH BRODSKY: (November 10, 1988) In order to live in a different country, you have to love something there. You have to love something there. You have to love either the spirit of the laws or the economic opportunities, or the--well, history of the country, the language perhaps, literature. I happen to love the latter two, but you ought to have some sentiment. You also have to, to--in my case, well, there is something else. I simply loved all my life, loved is the stronger word, but I had a tremendous sentiment, partly conditioned of course by the reality of which--of where I grew up--for the spirit of individualism, for the idea of your being on your own in a big way. Well, so in a sense, in a sense when I came here, this is what happened, this is what I found.

JIM LEHRER: Now two eminent poets on Brodsky and poetry in America today. Czeslaw Milosz won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980. He's a Professor Emeritus of Slavic Languages at the University of California at Berkeley. Robert Hass is the current poet laureate of the United States and a professor of English at Berkeley. Gentlemen, welcome to both of you. Mr. Milosz, how would you characterize Joseph Brodsky's poetry?

CZESLAW MILOSZ, Nobel Prize Winning Poet: (San Francisco) He was a very great poet and great successor of very great period of Russian poetry in the beginning of the 20th century. And he was my very close friend.

JIM LEHRER: Why does the word "great" apply to him?

MR. MILOSZ: Already since his beginnings and his trial in Russia the aura of greatness surrounded him. It's very difficult to define what it is.

JIM LEHRER: Mr. Hass, for those watching, listening now who have not read anything by Joseph Brodsky and this is the first time they're coming to his--he is coming to their attention, what would be your No. 1 recommendation as to what they should read to get the essence of this man as a poet?

ROBERT HASS, Poet Laureate: (San Francisco) I'd say to begin with, the first of his two books that were published in this country, Jim, a book called A Part of Speech. I guess the thing that should be said about Brodsky for us readers in English is that we're reading him in translation. He's a--he's a poet of immense verbal brilliance, lots of pyrotechnics, and when people try to bring that into English, what you often get is almost pyrotechnics, and almost brilliance, so partly you read his poetry in English as an act of faith, but I think the poems in the book A Part of Speech conveys the--his passion and his irony and a kind of a ferocious intelligence that will give people a sense of what he's like. His great work in English is the essays.

JIM LEHRER: The essays.

MR. HASS: And a book of his essays I think might be another place to get the quality of his mind and energy.

JIM LEHRER: In addition to the--reading the poetry.

MR. HASS: Yes.

JIM LEHRER: Yeah. When you use the term "pyrotechnic," are you referring to his uses of words,--

MR. HASS: Yes.

JIM LEHRER: --the way he arranges them, or his ideas?

MR. HASS: Both. All three.

JIM LEHRER: All three.

MR. HASS: But mostly, mostly the, the--he puns a lot. He plays a lot with language. He surprises with rhyme. There isn't much like him in American poetry right now.

JIM LEHRER: Yeah. Mr. Milosz, what was it about Joseph Brodsky that the Soviet authorities didn't like, that causes them to put him in, in--to try him and then put him in prison and then eventually to exile him?

MR. MILOSZ: You know, his attitude towards the world was sort of detachment and he really didn't acknowledge the existence of those authorities. He went his own way, and that was extremely irritating.

JIM LEHRER: And that's why--that was the only thing? I mean, he was not--he wasn't a--what you'd call a dissident poet, was he, in the--in what we normally refer to as people who are writing poetry against the state and all of that?

MR. MILOSZ: Not at all. He considered it below his dignity to quarrel with the state. He simply considered that the state is something ruled by low kind of individuals.

JIM LEHRER: Yeah. Mr. Hass, I read somewhere today that in describing where Joseph Brodsky came from, of course, which was Russia, they described it as the land of the poets. Are we a land of poets?

MR. HASS: Oh, I think we are. You know, one of the things that Joseph said about his years in Russia reading American poetry was that American poetry was for him a long lecture on autonomy, on freedom, and when he came here, he brought with him a passion for English language poetry, and he was one of the people who's made this country a sort of dazzling center of poetry in the world during the last twenty or thirty years.

JIM LEHRER: Mr. Milosz, do you see the United States as a dazzling place for poetry?

MR. MILOSZ: Yes. I must say that Joe Brodsky was very happy being in America, and I consider that America is better for poets than, for instance, Western Europe.

JIM LEHRER: Now, why is that? Because I say--the common thing here is that we are not a poetic people, that we are very pragmatic and we read our stories but we don't read our poetry, but you don't see it that way.

MR. MILOSZ: Well, judging by interest in poetry on the campuses, we would say that this is not quite true.

JIM LEHRER: Mr. Hass, I read today also that Brodsky said "that poetry is the only insurance we've got against the vulgarity of the human heart." And, in fact, I mentioned that in the News Summary at the beginning of the program. Is that a basic truth for you poets?

MR. HASS: Oh, I think it's a basic truth. You know, Yates, a great Irish poet whom Joseph loved, said it another way, he said, "We have filled our hearts with fantasy and our hearts grow brutal on the fair." One of the great things about poetry is that besides being an enchanter, it's a disenchanter, and a truth-teller, and Brodsky more than any other poet was one of those who managed to disenchant us out of the stupidity of our fantasies, and create more durable ones.

JIM LEHRER: Yeah. Would you agree with that, Mr. Milosz, that his poetry had that ability?

MR. MILOSZ: Yes. Yes. I consider that, that through his poetry one can apply the epithet sublime.

JIM LEHRER: Sublime.

MR. MILOSZ: Yeah. It's a very high praise, but undoubtedly his poetry is, is such. The trouble is, you see, and even I wonder his poetry is written in Russian, and it is in a way, its strength is linguistic, how it goes through translations, that's, that's another thing, not always go through translations.

JIM LEHRER: Sure. That was a point that Mr. Hass made a minute ago. Mr. Hass, you have a book of Joseph Brodsky's poetry there in your hand. Why don't--why don't you read a little bit. Tell us what it is, and give us--set it up, if it requires anything, and then read it, and we will say good night to you listening to Joseph Brodsky.

MR. HASS: Yes. Well, if Joseph was sublime, he was also amazingly clear and tough-minded, and here's a poem that--part of a poem sequence called "A Part of Speech" that might be a place to end:

JIM LEHRER: Mr. Hass, Mr. Milosz, thank you very much for being with us tonight.

MR. HASS: Thanks, Jim. It's a pleasure to be here.