Editor's Note: Normally, my stuff generates criticism from conservatives. This time around, the harshest abuse came from liberals. Sometimes, just to be fair and balanced, I have to write an article that disagrees, just a little, with those who are normally at my end of the political spectrum.

As the war drags on in Iraq, it’s become painfully obvious how little we learned from the Vietnam experience. But one thing that has changed this time around is that we aren’t blaming our soldiers for the sins of our leaders.

Everywhere, bumper stickers urge us to “Support Our Troops.” Sure, the government cut corners on armor for the soldiers and their vehicles, and hasn’t always taken good care of the wounded or provided sufficient funding for veterans’ benefits. And they keep sending the same troops back there, again and again, while extending their tours of duty. But these are Bush administration policies — the American people have demonstrated great respect for the troops forced to fight this misguided and mishandled war, and we are supporting the troops.

Even though most Americans now see the Iraq invasion as a mistake, protesters haven’t compounded that mistake by throwing garbage at returning GIs or calling them “baby killers,” as some did during the Vietnam era. The soldiers in the field didn’t make the decisions that created this mess — that blame rests squarely with the politicians and the electorate that put them back in office in 2004. Supporting the troops, even as support for the war they’re fighting drains away, is part of the compact we have with the brave men and women who defend us.

Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution designates the president as commander in chief. Civilian control of the military has been a cornerstone of our system for more than two centuries, because the founding fathers were wary of placing too much power in the hands of the military. Many of the framers had classical educations that taught them how the Roman Empire was devastated for centuries by a succession of generals who waged one civil war after another.

Because we limit our military to determining tactics, rather than deciding geopolitical strategies, the commander in chief is a civilian. Even when our president is incompetent, this arrangement is preferable to becoming an unstable “banana republic,” where military juntas overthrow their governments if they don’t like the way the civilian authorities are running things. And civilian control is also better militarily — how can the armed forces implement cohesive national policies if individual generals are determining which campaign is a good idea?

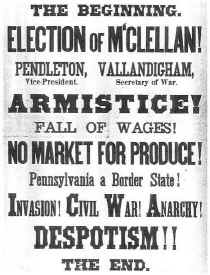

| American military officers are expected to obey the elected authorities unquestioningly until they’ve completed their military service. Problems in that area forced President Truman to fire General MacArthur during the Korean conflict. On the other hand, now that he’s retired from NATO, Wesley Clark is free to criticize the Iraq war, just as former general George McClellan was free to oppose President Lincoln and criticize his handling of the Civil War during the 1864 presidential election. |

|

At the same time, there’s a corollary to this arrangement we have with our men in uniform: Just as they don’t get the blame when our country wages senseless wars, they don’t get to decide when they, as individuals, can opt out of such conflicts.

Earlier this year, the court martial of Lieutenant Ehren Watada, the first commissioned officer to publicly refuse to deploy with his unit to Iraq, ended in a mistrial, and his retrial remains up in the air. Lt. Watada planned to defend his actions by claiming that the war is unjust; however, the presiding judge, Col. John Head, quashed this defense, deeming it beyond the court’s jurisdiction.

Judge Head’s ruling was entirely appropriate. The place for debates on the legality or morality of the Iraq war is the Senate floor and the Oval Office, not in a military courtroom. If Lt. Watada didn’t understand that his enlistment meant he might have to fight in an unpopular war, then his superiors should have explained it to him.

|

|

Had he been a draftee, Lt. Watada might have had some justification for refusing to serve in a theater of operations that violates his conscience, but this is a volunteer army ... and he volunteered. Military service isn’t a cafeteria: Enlisted men don’t have the right — which Watada had hoped to assert — to decide to fight in Afghanistan, but not in Iraq, regardless of the relative merits of the two engagements. Watada has become a cause celebre on the left. Antiwar activists have cheered his actions, but, in this case, they’re wrong. The overriding issue here is the compact between America and its men in uniform. |

During the trial, Army prosecutor Capt. Dan Kuecker described Watada’s actions as contemptuous of President Bush. As citizens, we have the right — and, based on his performance during the past six and half years, an obligation — to be contemptuous of our president. But Lt. Watada was court martialed as a military officer, for insubordination toward his commander in chief, which is not his right — a fact he should have realized when he enlisted.

We Americans have an obligation to support our troops, even if we might oppose the war they’re fighting. The other half of this bargain is the soldiers’ obligation to do the job they’ve signed up for. Those who refuse risk losing their nation’s support.

Click here to return to the Mark Drought home page.