_________________________________________________________________

Editorial

Rome (Ga.) News-Tribune

Wednesday, November 11, 1998

*****^^^^^*****

Educators argue, probably with good reason, that the citizens/parents/taxpayers pay entirely too much attention to standardized test scores and rely on them to judge how "good" the public schools are.

That's true, at least in the sense that the acquisition of raw knowledge is not nearly as important as how that knowledge is ultimately used. The only test for that is known as life.

Nonetheless, test numbers can sometimes tell the public things other than how much learning has been crammed into little Johnny or Jane's skull. That may have been the case when the Rome and Floyd County systems recently released their 1998 Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) scores. These are given to all third-, fifth-, and eighth-graders.

Let us consider the data for third-graders, the youngest taking the tests and thus those for whom the school systems should have the most remaining time to correct whatever might be perceived as inadequate.

The national average score of the ITBS is a 50. Half the children score lower; half score higher. In a state such as Georgia, which has a less than stellar reputation regarding quality of education, a score of 50 is actually pretty good. The state generally came out in the low to mid-50s on most sections of the test (reading, math, social studies, science).

OK, maybe it's nothing to shout about that state students as a whole, and Rome/Floyd County students in particular, are just about "average", but that's plainly better than the below-50 alternative.

What's interesting about the local scores, and perhaps grist for some public discussion, is this: There's a striking difference between some schools.

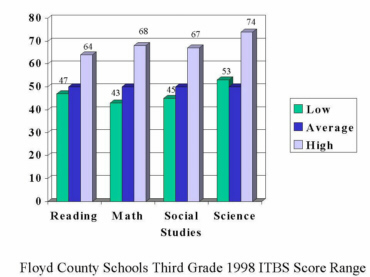

In the county, the difference from one school to another ranged, in reading, from 64 for the "best" elementary school third-graders to a "worst" of 47. In math, it ranged from 68 to 43. In social studies, from 67 to 45. In science, from 74 to 53. (Figure 1 displays results for Floyd County Schools Third Grade 1998 ITBS Score Range.)

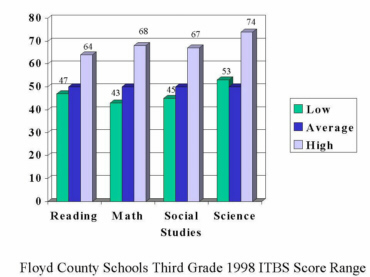

In the city system, the width of the gap between locations was even more noticeable. In reading, 75 to 27. In math, 78 to 38. In social studies, 83 to 27. In science, 85 to 30. (Figure 2 displays results for Rome City Schools Third Grade 1998 ITBS Score Range.)

At the lower end, these numbers show that some of Greater Rome's children are not performing up to even average. Indeed, some of them are apparently limping along near the bottom.

The reasons for these differences are not hard to understand, at least in part. Most of the lowest-score schools teach children who come from known problem home environments - poverty mostly.

Our schools can't do anything about the poverty, of course, nor about the fact that race and poverty often seem to go hand-in-hand. That's a wider public issue and not an unfamiliar one.

The question raised by the sometimes huge variation of these numbers is something else again. Clearly, some of this region's children simply aren't learning as much as others. Yet, all of them will ultimately be competing for the same jobs and careers.

What's disturbing, or should be to everyone, is that some very young children are being left behind. It is, based on the schools with the weakest records, not difficult to predict where tomorrow's high school dropouts are going to be coming from.

While all of us should want something better than "average" for our children and grandchildren, the main worry that these test results should suggest is this: How do we bring all the children up to a level of being at least average in the classroom?

Their family incomes can only be changed with difficulty; their race or ethnic heritages can't be changed at all. What can be changed is the quality and intensity of what they are receiving in the classroom.

In talking with educators, it is plain that once upon a time, not so long ago, wide swings in numbers such as this would have resulted in fundamental shifts of resources that may not be occurring today. Not necessarily money resources, either, but more along the lines of teaching resources.

A weak school once would call for the transfer of the best teachers - in the sense of being able to motivate - to that location. Nowadays, some educators contend, the trend is to give the "best" teachers to the "best" students to raise them up even higher.

In a sense, the devil is being left to take the hindmost students. They are being "written off", possibly as early as the third grade.

The local school systems recently argued, unsuccessfully, that they needed more money for new or improved buildings. Others, including this space, responded that bricks don't teach and additional outlays, if needed, should emphasize what happens inside the classroom.

These numbers not only reinforce that latter argument, they indicate the real direction which this community's concerns should take.

For some children, at the same grade level in the same school system, to be scoring up to three times better in an area of learning than at another school across town or county is unacceptable. Our society has no minds to waste.

When it comes to education, that's what this community must begin to discuss...and repair.

Back to A Challenge to Discuss... and Repair

![]()