The

Battle of Stirling Bridge

|

|

With his army swollen to 40,000

lightly armed foot soldiers and about 180 horses, Wallace

took up the postion on the steep sided high ground now

known as Abbey Craig, looking across the Forth to

Stirling and its vital castle. His men, who would have

made the most of their own weapons, used 12ft long

spears, axes and knives and wore rough hide tunics or

homespun cloth; few would have had helmets or any form of

body armour. The English

Governor of Scotland, John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey,

commanded a force of mail-clad cavalry, skilled longbow

men from Wales and well- weaponed infantry, in all

numbering 60,000, with 8000 in reserve.

|

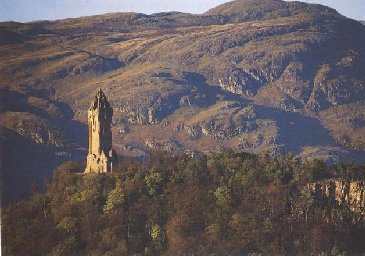

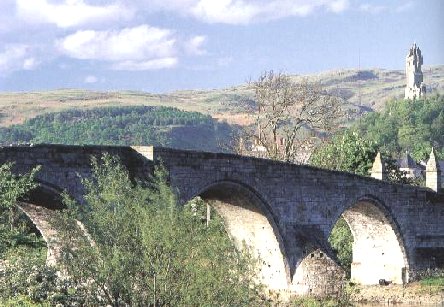

Wallace

monument on the Abbey Craig, Stirling.

|

|

|

This was to be Wallace's first

experience of a standing battle as against guerilla and harrying

actions.

| If Warenne, with his stronger

and more disciplined force, could engage Wallace's men he

would achieve a decisive victory, and, by killing or

capturing Wallace, end all opposition to Edward. But he

had a problem. The Forth lay between him and his

objective, and there was just one narrow wooden bridge

across it. He rejected the suggestion of using a ford

frther upstream, which would have caught the enemy in

thre rear, on the grounds that it would divide his army;

it is more likely that he suspected treachery. While he

hesitated, Hugh de Cressingham, Edward's Treasurer of

Scotland, protested against 'the waste of the king's

money, in keeping up an army, if it was not to fight'. |

|

|

| |

|

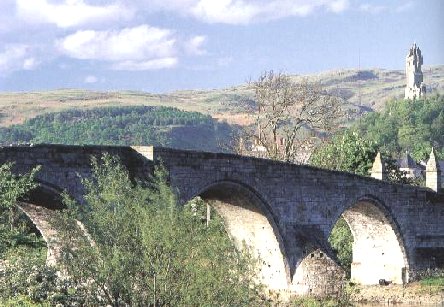

The Stirling

Bridge today, thought to be very close to where the

original stood.

|

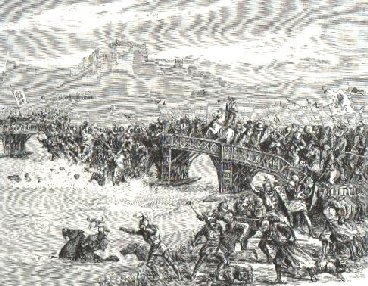

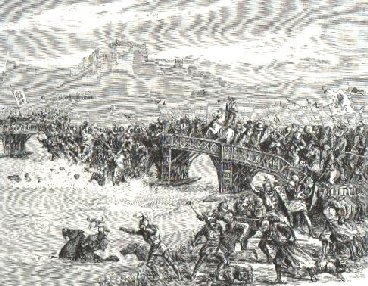

With that prod and the encouragement of

his men, many of them seasoned veterans of Flanders and Wales,

Warenne ordered that the infantry should start crossing the

bridge at dawn the following day, 11th September 1297. He flat

ground beyond the brudge was marshy, and any attack would have to

be made along a causeway and then uphill. From Abbey Craig,

Wallace had a perfect view of the thin file of English fanning

out from the bridge to pick their way hesitantly over the

treacherous ground while his force lay in hiding at the foot of

the Ochil Hills on their flank. It was the perfect situiation for

an ambush, with Wallace able to dictate the terms on which he

would fight.

|

|

At the critical moment he gave

the order and the Scots charged down the slopes to reach

the bridgehead and trap a manageble number of the enemy

who perished intheir thousands, caught between the

Scottish spears and the river. What cavalry had crossed

the bridge was son floundering in the boggy ground, and

those fighting to get back over it were blocked by those

still advancing. Only one, Sir Marmaduke de Twenge,

succeeded; he spurrd his horse through the press at the

bridge, no doubt killing and injuring many of them. His

reward from Warenne was the order to assemble whatever

forces he coud muster and occupy the now doomed Stirling

Castle. Warenne himself then mounted his horse and rode

forthe safety of Berwick. Cressngham, who had an odious

reputation even among the English and had been

particularly barbaic in oppressing the Scots, was killed

in the battle. |

The Scottish losses at Stirling Bridge were relatively light, but

the great loss to Wallace was the death of his faithful friend

and joint general Sir Andrew Moray. This victory, followed by a

string of successes, including the surrender of Edinburgh Castle,

quickly restored Wallace to the favour of the vacillating

Scottish nobles. Campaigning in Flanders, Edward receieved the

news that ' this leader of a little band of outlaws, this plebian

without family, influebce or wealth, supported by merit alone,

had wrenched from the English every fortress in Scotland'.

back to History index

HOME

This

page created on 17th April, 2000