Stones of Stenness, Orkney The imposing monoliths at Stenness were once part of a henge.Only four of the stones are still standing, but orignially there were 12. Radiocarbon tests on animal and charcoal deposits found at the site indicate that the henge dates back to the 3rd millenium BC. In more recent times, it was the centre of a popular fertility cult. Local couples would make thier vows withing the circle and then join hands at the nearby Stone of Odin - a single standing stone which was destroyed in 1814. |

||

Jarlshof, Shetland Jarlshof's Norse sounding name was invented by Sir Walter Scott, who visited the site in 1814 and used it as the setiing for his novel, The Pirate. However, subsequent research has revealed that some remains are significantly older, dating back to the second millennium BC. Here, the foundations of a prehistoric house can be seen, together with a stone hearth and quern(a surface that was used for grinding corn) |

||

The Cuillins, Skye Skye's famous mountain range attains heights of well over 3000 feet and can be seen for miles around. The peaks used to be spelled in a variety of different ways, including Cuchullin. This has fueled speculation that they were named after the lengendary Irish hero Cu Chulainn. Even today the silhouette of the mountains is often likened to a giant sleeping warrior |

||

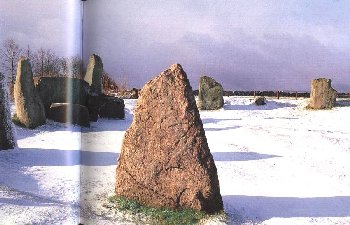

Easter Aquhorthies, Inverurie, Aberdeenshire This is a fibe example of a recummbent stone cirlce - a circle where the 'entrance' to the ring is marked by a massive horizontal stone, flanked by two tall portal stones. In this, as in other similar monuments, the entrance is sited in the south-western quadrant of the circle. A distinction can also be made between the granite of the entry stones and the pinkish porphyry of the remaining boulders. Early commentators interpreted the horiontal stone as a pagan alter, but its true purpose remains uncertain. |

||

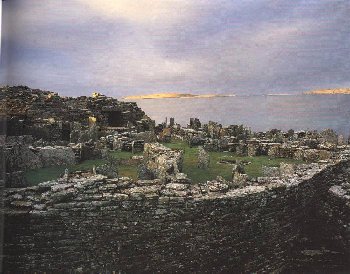

Broch of Gurness, Orkney The settlement at Gurness spans many centuries, beginning in the Iron Age, when the massive broch was constructed. Among later inhabitants were the Picts and Vikings. The former left behind one of their earliest symbol-stones, dating from the 6th century, while the principal Viking find was the tomb of a woman, laid to rest with bronze jewellery and iron implements |

||

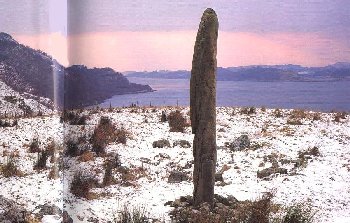

Kintraw, Argyll Situated at the head of Loch Craignish, the prehistoric site of Kintraw contains 4 cairns and a large standing stone. The latter rises to a height of 13 feet (4 metres) and is often cited in discussions about ancient observatories. From this viewpoint, the light of the setting sun at the midwinter solstice falls precisely in the notch between the twin peaks of Beinn Shiantaidh and Beinn a Chaolais, almost 30 miles (48 km) away on the island of Jura. Some experts believe the standing stone was deliberately positioned here, to provide a marking post for this phenomenon. |

||

|

|

The Standing Stones of Callanish, Lewis Sometimes described as Scotland's Stonehenge, Callanish is laid out in a unique formation. At its core there is a stone circle, with an avenue (a double line) of stones leading north, and single lines leading east, west and south. Within the circle, a chambered cairn and central pillar stone are jointly aligned, so that the latter's shadow penetrates the tomb on the equinoxes. Callanish is the focus of many legends, among them a belief that the stones are the petrified victims (the False Men in Gaelic) of Druid priests |

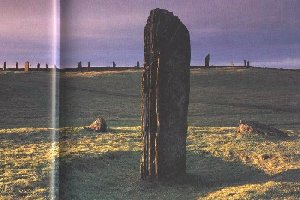

Ring of Brodgar, Orkney The Ring of Brodgar is both the most northerly and the most famous of Scotland's henges. In its original state, it formed a cirlce of 60 stones - 27 of which remain - with a diameter of 120 yards (109 metres). The site is probably related to the Stones of Stenness (see above) which are situated just 1 mile (1.6km) away. Early visitors believed that these henges were sun temples, but recent research suggests that they may have been designed as lunar observatories. Whatever their purpose, they continued to fascinate later generations, for one of the stones bears a runic inscription. |

||

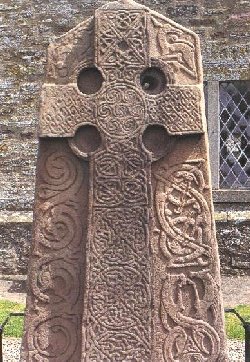

Cross-slab, Aberlemno, Angus Three Pictish stones have survived at the village of Aberlemno : a tilting pillar covered in enigmatic symbols and two cross-slabs. These details come from the older of the two slabs, which probably dates from the 8th century. On one side, it bears a Celtic cross, carved in high-relief and set against a background of interlacing, snake-like monsters. On the reverse, a pitched battle between helmeted and bare-headed warriors is shown. This may represent the battle of Nechtansmere, where the Picts had won their famous victory over the Angles. This battlefield was just a few miles away from Aberlemno, and surviving Anglican helmets, with their long nose-guards, are similar to those portrayed on the stone. |

||

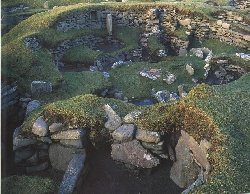

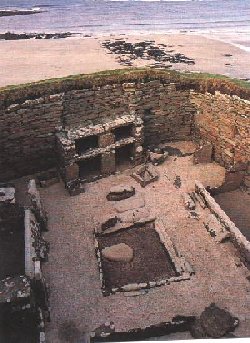

Skara Brae, Orkney This extraordinary neolithic village lay buried under sand for centuries, until a freak storm revealed its existence to archaeologists in 1850. Ten houses have survived , the oldest of which dates back to c. 3200BC. Inside, the stone fittings provide a telling insight into the inhabitants way of life. Here, a dresser and hearth can be seen, along with stone beds and larder-pools for fish. |

||

|

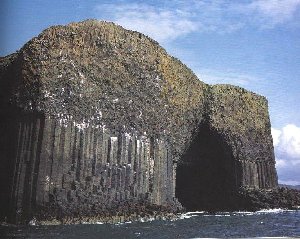

Fingal's Cave, Staffa The striking basalt columns that line Fingal's Cave were caused by a series of volcanic eruptions, running between Skye and the Irish coast. Similar rock formations were created elsewhere, most notably at the Giant's Causeway on the North coast of Ireland. Both these geological wonders were ascribed to the same legendary figure: the 3rd century Irish warrior-hero, Finn MacCool, known in Scotland as Fingal and often portrayed as a giant. He was said to have built a magic bridge between Ireland and the Hebrides, so that he could visit his sweetheart in the Scottish Isles. |