The idea for this

book was as spontaneous as most of the Haymarket Anarchist gathering

itself. The difficult part has been the more tedious aspect of organizing

it and getting ourselves motivated after periods of inactivity concerning

the compilation of the materials. It has been a year since the Haymarket

gathering in Chicago and our goal was to have the book ready for the second

gathering to be held in Minneapolis in l987. Deadlines are such motivators

even for anarchists.

The idea for this

book was as spontaneous as most of the Haymarket Anarchist gathering

itself. The difficult part has been the more tedious aspect of organizing

it and getting ourselves motivated after periods of inactivity concerning

the compilation of the materials. It has been a year since the Haymarket

gathering in Chicago and our goal was to have the book ready for the second

gathering to be held in Minneapolis in l987. Deadlines are such motivators

even for anarchists.

Our final decision to drastically cut many of the contributions due to the amount of material we received may not meet with much approval, but we hope the book will stand on its own. We think it does. We tried to include something from everyone, but again that was not always accomplished due to many repetitious accounts. We also decided to include sections which required that we put bits and pieces of accounts in different areas of the book. This was done to give a sense of continuity to the work in terms of chronology. At the same time, we tried to include various accounts and experiences in their entirety in order to maintain the personal experiences that people had in a more individualistic way. We hope that this method helps to construct an historical picture that is built from many points of view rather than one person's vision of an historical event. Anarchy has had enough of the singular historian's biases.

We had over 70 contributors to this book and about half that many contributing various sums of money to the project. Our decision to only include first names or pseudonyms was not intended to slight anyone; it was meant to maintain a flavor of anarchism that does not glorify heroes, leaders or personalities. It is the same with the people who contributed money to the project. $l00 was as important as those who sent only their best wishes to the project and the deletion of names merely reflects that belief.

We present this book in the spirit of the convention: anarchy in action. The historical importance of this little compilation remains to be seen. The events of Haymarket '86, however, are important for all of us to consider if we are to build a viable revolutionary movement here in the U.S.

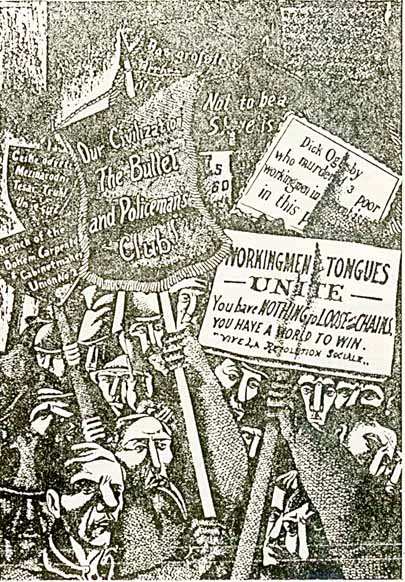

On May l, l886, workers from all trades and factories throughout the U.S. went on a general strike in support of the eight-hour work day. In Chicago, a stronghold of immigrant labor and anarchists, 80,000 workers marched in an "eight-hour day" demonstration. The Central Labor Union (a revolutionary union federation organized by anarchists which had quickly become Chicago`s largest and most active union center) and the anarchist International Working People`s Assocation organized these strikes and demonstrations, which not only called for shorter hours, but also called on workers to organize and overtake their industry and society.

Before the strike action began, the management at McCormick Machine Co. (then International Harvester, now Navistar) locked out 1,500 workers over a wage dispute. On May 3rd, when pickets attempted to prevent blackleg labor entering the plant, the Chicago police opened fire on the workers, killing at least two and wounding many others.

A protest was called for the following day at Haymarket Square. Speeches condemning police violence and capitalist oppression were given by three leading anarchists: Albert R. Parsons, August Spies, and Samuel Fielden. As Fielden, the last speaker, was concluding his address, about 200 police attacked the crowd. An unknown person hurled a dynamite bomb at the advancing police lines, killing one policeman and wounding many others. Police went wild and immediately shot scores of people, killing at least four demonstrators and even six policemen.

This was used as a pretext to launch the first major "red scare" in American history. The capitalist press across the country whipped up the flames of hysteria, with the New York Times prescribing Gatling guns and gallows to prevent the spread of Anarchist thought. Chicago police launched a general roundup of radicals and unionists, raiding homes, meeting places, and newpaper offices. Hundreds were arrested and interrogated under virtual martial law, with anarchist newspapers suppressed (and their editors jailed), mail intercepted, and union meetings and public gatherings banned.

On May 5th, 300 of Chicago's "leading citizens" put up over $l00,000 to hire witnesses and subsidize the repression. On June 21st, eight anarchists prominent in the Central Labor Union were put on trial, even though most weren't even present at the Haymarket demonstration. All eight were ultimately convicted by a hand-picked jury. Of the eight, Albert R. Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel were hanged on Black Friday, November 11th. Louis Lingg committed suicide the day before in his jail cell. Oscar Neebe, Michel Schwab, and Samuel Fielden spent six years in prison before being pardoned. All eight were later shown to have had nothing to do with the bombing.

On July 14, 1889, on the hundredth anniversary of Bastille Day, an American delegate attending the International Labor Conference in Paris proposed that May 1st be officially adopted as a workers' holiday. This motion was unanimously approved and since then, May Day has served as a date for International working class solidarity.

[Click here for more about the 1886 Haymarket Massacre.]

One hundred years after Haymarket, millions are still working and living in dire poverty, unemployed, prevented from organizing and defending their rights and interests by government (regardless of their professed ideologies) and bosses.

Obviously, we can see that it is still time for A change! And time to confirm those last words of Spies: "There will be a time when our silence from the grave will be more powerful than those voices you strangle today!" LONG LIVE ANARCHY!

About l2 of us from Detroit made the trek to Chicago this May Day to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Haymarket riot and subsequent state murder by execution of five anarchists.

Hosted by the Chicago Anarchist Group, the gathering was attended by 300 to 400 people--about 2/3 male, mostly white, mostly young, with hardly any oldsters and only a few people over 40. Participants came from all over the U.S. and Canada, with a small number of visitors from outside North America.

The gathering consisted of workshops, theater, music, art shows, participation in a May Day march, an anarchist march of our own, a banquet and a memorial gathering at the gravesite of the Haymarket martyrs.

We were able to participate in only a few of the workshops held,

but we found much of the discussion stimulating, if at times disjointed.

Workshop topics included ecology; a weirdly formulated "tech vs. anti-tech"

(which none of us were able to attend as this workshop was held on the

same day); Spain 1936 (which unfortunately, but perhaps inevitably, turned

into a discussion on Central America); building the anarchist movement

(which according to one participant degenerated into the age-old hot air

sessions about computer networks, a national federation and a national

press); personal politics and anarchy; what is anarchy?; and anarchy and

social revolution/why revolutions fail.

Of course, there were many informal discussions as well, but despite

meeting new friends and old, those of us from the Fifth Estate missed talking

with many people from around the country, including FE sustainers and others

with whom we would have liked to make contact. It was an exciting time,

in spite of the craziness and chaos, and we wish we could have spent more

time at it.

On Thursday, May l, anarchists and other conferees participated in

the traditionally marxist Pilsen march (an old German workers' district,

now a Latino barrio), spontaneously leaving the march at one point and

coming close soon afterwards to a major cofrontration with Chicago's cops.

During the standoff, the marchers finally had to disperse, but managed,

after some negotiation, to free two people who had been arrested.

"EVERYTHING AND NOTHING"

On Friday, conference participants had our own march, a tour with no

permits to such monuments to Authority as the jail, city hall, the stock

exchange (where toy money was thrown at businessmen, and brokers watching

us from the windows above were urged to jump by the crowd), IBM, the South

African Consulate, the struck Chicago Tribune, and a fancy shopping district

where the proverbial shit hit the fan, and 38 people were arrested for

disorderly conduct, "mob action against the state," and one person for

desecrating a U.S. flag (now a felony).

At an intersection near the stock exchange where we momentarily blocked

traffic, a well-dressed older woman was overheard asking a cop, "What organization

is this?" He replied, "They're not any organization, they're anarchists."

And to her question, "What do they want?" he replied with astonishing

perspicacity, "Everything--and nothing."

The scene at IBM was exhilarating--one of the wildest scenes I can

remember in many years of demonstrations. Amid war whoops, screams and

chants of "IBM out of South Africa, South America," etc. until every contingent

got covered, people blockaded the building and closed it, and many proceeded

to pound on the plate glass windows and the metal coverings on the pillars,

creating a great din. (I saw one anarchist @ drawn on the window while

the geeks in suits gaped incredulously from the other side.) Money and

a flag were burned, which almost caused a brawl with the cops, but they

still did not attack, which we found amazing at the time. Remember, this

is the force that massacred workers a hundred years ago, that massacred

workers during the Republic Steel strike in 1937, and perhaps many of the

same cops who attacked peace demonstrators in 1968, and who slaughtered

the Black Panthers in their beds in 1969, and who brutalize people every

day in Chicago's poorer neighborhoods.

The cops had been following us all along in large numbers, hissing

that the march was a "cattle drive" and that at the end they would all

have their own Haymarket commemoration, each "take his own anarchist to

lunch," as someone later reported being told. The mob was meandering, and

for those of us not from Chicago, we felt a little powerless to control

events. By IBM, things were threatening to go beyond the point of no return,

so some of us decided to make our own way to the cop monument to Haymarket,

where the march was supposed to end.

(This is the base of the statue built in 1889, funded by Chicago capitalists

after a public "popular subscription fund" promoted by the Chicago Tribune

raised only $150 in ten months. This statue has had an interesting history

of its own, including bombings and vandalism. In 1927, on the 41st anniversary

of the Haymarket meeting, a streetcar driver drove his car full speed and

jumped the track, knocking the statue off its base. In 1968, the statue

was defaced with black paint, and in 1969 and 1970 it was blown up. In

Fedruary 1972, the staue was removed from the base and moved to Police

Headquarters, before finally going to the Police Academy, in an area not

accessible to the public. On May Day 1972, anarchists and Wobblies tried

to place a paper mache statue of anarchist Haymarket martyr Louis Lingg

on the base, but the cops turned out in force to prevent it.)

We finally found the statue base after taking a few wrong turns, but no one else showed, though there were plenty of anarchist @`s spray painted nearby. The statue inscription read, "From the City of Chicago in honor of her heroes who defended her against the riot." A friend etched out "heroes" as best he could and wrote "murderers" in its place.

DANCING IN THE NUDE

We learned later that after IBM, a similar scene had ensued at the South African Consulate and the Chicago Tribune (where marchers fraternized with striking workers), and approaching a bourgeois shopping area, some people had begun runinng in and out of stores and a window was broken in a hotel. There the cops began arresting people who had started to disperse, grabbing those who looked nonconformist or who carried flags, who ran too slow or ran too fast, or who tried to investigate the arrests of others.

That night, there was a lengthy discussion about the demonstration while a small group worked frenetically to get people out of jail. There was much heated discussion on responsibility, how to do demonstrations, decision-making, tactics, and the arrest, which was all very interesting but inconclusive.

On Saturday night after a day of workshops and prisoner support, there was a banquet, conversation and dancing. (Some folks danced in various states of undress, which prompted an old-timer to remark that he was surprised that so much fun could be had with so little liquor, but, frankly, "In 1936 we were dancing in the nude.") By this time everyone had gotten out of jail, and the air was festive. We had made our points here and there, and everyone felt enthusiastic about rubbing shoulders with other strange people like ourselves.

On Sunday, we went to Waldheim Cemetery where the Haymarket victims are buried (along with Voltairine de Cleyre and others). There was a brief scuffle with liberals and stalinists over a black flag hung on the monument, but in the end it stayed. People drank champagne and took snapshots of each other, finally gathering at the grave in a linking of arms to shout some spirited hurrahs for anarchy. I may be a sentimental fool, but I loved it. And we made our point--the Haymarket victims were not liberals, labor reformists, or historians. They were unrelenting rebels who had the courage and the vision to demand the impossible in an impossible society. That is why they were hanged--as the state's attorney declared, it was anarchy that was on trial--and that is why the last words of George Engel and Louis Lingg were "Long Live Anarchy."

In spite of any criticisms, it was exciting to be there with so many people who, even if their interpretations varied widely, were drawn to an event based on those last defiant words. Let no one be mistaken: anarchy cannot be stamped out. Anarchy lives.

---Dogbane Campion

We didn't get much out of any of the workshops we attended, but we did get a lot out of just talking to people, getting to meet our pen-pals, etc. Final verdict: we did meet horrible leftist men, we did meet very nice ones, great girls too, but not enough of them, etc. What the fuck, let's all do it again next year.

---T.H.R.U.S.H.

(Terrifying Hags Ruthlessly Uprooting Self Hatred)

Send comments to: brian_krueger@htomail.com

Updated: Nov 98