Practice and Ceremony

The following information is based upon my personal field research in Salvador, August 1997. -A.S.G.

The belief system of the Candomblé is very organic and traditional. They worship the purity of the natural universe. There is an emphasis placed on living a life free of negativity and doing good towards the people in their communities. Practitioners are free in the sense that they are liberated spiritually from the evils of the material world. Order and respect of the body, mind, and soul are vital in the practice of Candomblé. Respect and worship of the orixás is the backbone of this belief system for they represent the natural elements present on earth and embodied in spirit.

Opening offering to "Exu"

The ceremonies of the Candomblé are very long and energetic. They almost always begin with an offering to Exú, the trickster orixá. In syncretism he is associated with the devil; however, many Candomblé practitioners look down upon this characterization. Being the trickster that Exú is, it is necessary to please him with a despacho (food offering) of popcorn and flour mixed with palm oil. This offering pleases Exú and ensures that he will not interfere with the ceremony’s proceedings. He is also the intermediary between the people and the orixás. Therefore this offering is a very important insurance for a successful ceremony.

At the Candomblé ceremony of Terreiro Oya Pade, which I attended in its entirety, the offering to Exú was placed on the leaf covered floor. The leaves are of the aruiera tree and serve as a spiritual attachment with nature for the dancers in the circle. Men sat on one side of the small room and women on the other. The ceremony began with fireworks exploding on the street in front of the terreiro. This was the a call to the community that the ceremony in honor of Omolú was about to begin. This particular terreiro practices syncretism and celebrates feast days honoring orixás on the same calendar days as their respective saints. This celebration was held on the feast of Saint Lazarus who, in Candomblé, is Omolú, the orixá of pestilence.

Once the offering to Exú was taken from the center of the room, the initiated practitioners came out to the center of the dance floor. They greeted one another by kissing each others’ hands. The practitioners bowed to the feet of the Mãe Estela, the mother of this terreiro of Candomblé. The audience greeted one another and paid their respects to the practitioners and the mãe. After a few minutes of greetings the drums gave the opening call to the orixás. The intoxicating rhythm was present and the ceremony had begun.

The drummers began to play as the practitioners brought out large pots of food. The food was placed on the floor on top of a white cloth and straw mat. Mãe Elise sat on a stool and began to serve the food on folhas de mamona (castor-oil leaves) and passed the leaves around to the others who placed more food on the leaves. The foods prepared were all special foods of the orixás. Every person in attendance at the ceremony received a leaf of food and ate with their hands. The musicians played throughout this portion of the ceremony as the practitioners laughed and sang while feeding the entire congregation. There was so much happiness displayed in this poor terreiro of Salvador. It is very reflective of the African traditions and values centered around the community. Candomblé feeds its community the food for the body and food for the soul.

The food of the Orixás.

Some mães believe that it is their role to take care of the mediums during mounting and they choose not to receive. Receiving an orixá is avoided by drinking a glass of clod water. Mãe Elise does not agree with this practice, she was mounted by Omolú during the service.

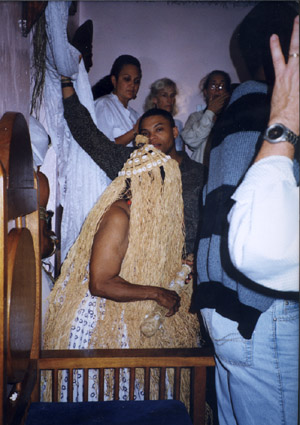

Following a fairly long intermission, the mounted mediums were brought out into the main room in traditional African costume of their respective orixás. The drummers began to play the special music of the orixá of honor, Omolú. The two mounted mediums, Mãe Elise and a filha de santo, danced alone together in the center of the room to the songs of Omolú. As the music and dance increased in intensity, the congregation began to clap and cheer for the orixás. It is believed by the members of Candomblé that the orixá is controlling the mediums body. The two women who were taken by Omolú are in their early seventies and normally would not be able to dance with the same energy. This is the power of axé.

Omolú god of pestilence

and disease.

The ogans escorted the orixás

out of the main room after their featured dance. As the featured orixás left the floor,

the next group of orixás took the dance space. The orixás who were waiting to dance

stood along the exterior of the dance circle with their eyes shut. Some of the orixás

placed their hands on their waists with both hands together as if covering a wound or on

their faces like the international sign for sleep. In between songs one could hear a high

pitched hum or call from some of the orixás. There were even some small conversations

between the ogans and the orixás. In some cases the ogans were stabilizing

the orixás from falling over. The medium’s body would shake and fall forward but the

ogan stabilized the orixá by placing his hand on the mid section of the

medium’s spinal cord.

Omolú god of pestilence

and disease.

The ogans escorted the orixás

out of the main room after their featured dance. As the featured orixás left the floor,

the next group of orixás took the dance space. The orixás who were waiting to dance

stood along the exterior of the dance circle with their eyes shut. Some of the orixás

placed their hands on their waists with both hands together as if covering a wound or on

their faces like the international sign for sleep. In between songs one could hear a high

pitched hum or call from some of the orixás. There were even some small conversations

between the ogans and the orixás. In some cases the ogans were stabilizing

the orixás from falling over. The medium’s body would shake and fall forward but the

ogan stabilized the orixá by placing his hand on the mid section of the

medium’s spinal cord.

The other orixás involved in the ceremony were Oxum, Oxossi the hunter, Ossaim, Ogun, Yansan of the storm , and four Oxums of different personality types. The Oxums’ personality types were distinguished by different colors: pink, yellow, orange, and peach. The costumes of all the orixás were very elaborate with certain props for each. For example, Ogun had a sword that he used during his dances while Oxum held flowers and a mirror to admire her beauty during the dancing. These props and costumes can be purchased at the many orixá stores in the commercial areas of Salvador.

While the drummers were packing up and the people were leaving, I ate cake in honor of Omolú with Mãe Elise. As we spoke to one another an older filha de santo approached Mãe Elise. The medium was being ridden by Eré, the child orixá who sometimes appears before the medium is back to normal. The woman was speaking like a child, laughing, and running around the room visiting with the remaining people and sharing the powers of axé.

Don't rely on the internet for all of your information: Read a book!

Here are some good resources:

Amado, Jorge. Tent of Miracles. New York: Alfred Knopf, Inc., 1971.

Amado, Jorge. The War of The Saints. New York: Bantam Books, 1993.

Bramley, Serge. Macumba. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1977.

Brown, Diana DeG. Umbanda: Religion and Politics In Urban Brazil. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Browning, Barbara. Samba: Resistance In Motion. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1995.

Burns, E. Bradford. A history of Brazil. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia Univeristy Press, 1980.

Galemba, Phyllis. Divine Inspiration: From Benin to Bahia. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1991.

Hess, David J. Samba in the Night: Spiritism in Brazil. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Pattee, Richard, trans. The Negro In Brazil. By Arthur Ramos. Washington: The Associated Publishers, Inc., 1951.

Pierson, Donald. Negroes In Brazil. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1942.

Smith, T. Lynn. Brazil: People and Institutions. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1954.

Smith Omari, Mikelle. From the Inside to the Outside: The Art and Ritual of Bahian Candomblé. Published by the Museum of Cultural history, at UCLA. Currently out of print, check your library.

Wafer, Jim. The Taste of Blood: Spirit Possession in Brazilian Candomblé. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

This page hosted by ![]() Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page