|

Although

nihilism is often thought of as a vague concept relegated to the

arena of philosophy or perhaps as the unavoidable conclusion to

post-modernist thought, nihilism does have a strong historical

background that deserves greater recognition. The most

significant manifestation of nihilism in recent history also

coincides with its most active and organized expression, that of

the Russian nihilist revolutionaries who rose to prominence in

the 1860s.

The Russian

nihilists (the Russian word for nihilist is nigilist)

tend to be associated with violence, revolution, and

terrorist acts such as the assassination of Czar Alexander II by

the ‘Will of the People’ group.

But although violent acts get

recorded in the history books often the lasting impact is

carried through non-violent ideas and identities. The Russian

Nihilists were intriguing in this regard for their history is

like that of an iceberg – only a small portion of their total

character is readily visible. Indeed, much of the violent acts

associated with the attempted overthrow of the monarchy occurred

under the auspices of other groups such as anarchists, Marxists

and narodnichestvo populists in the 1870s, rather than

those directly associated with the Nihilists themselves who were

much more complex than the over-simplified ‘terrorist’ label

attached to them by autocratic authorities.

“Nihilism

was not so much a corpus of formal beliefs and programs (like

populism, liberalism, Marxism) as it was a cluster of attitudes

and social values and a set of behavioral affects—manners,

dress, friendship patterns. In short, it was an ethos.”

[2] But although violent acts get

recorded in the history books often the lasting impact is

carried through non-violent ideas and identities. The Russian

Nihilists were intriguing in this regard for their history is

like that of an iceberg – only a small portion of their total

character is readily visible. Indeed, much of the violent acts

associated with the attempted overthrow of the monarchy occurred

under the auspices of other groups such as anarchists, Marxists

and narodnichestvo populists in the 1870s, rather than

those directly associated with the Nihilists themselves who were

much more complex than the over-simplified ‘terrorist’ label

attached to them by autocratic authorities.

“Nihilism

was not so much a corpus of formal beliefs and programs (like

populism, liberalism, Marxism) as it was a cluster of attitudes

and social values and a set of behavioral affects—manners,

dress, friendship patterns. In short, it was an ethos.”

[2]

Historical

Context

In order to

understand who the Russian Nihilists were we first have to

understand what the fought against and why. Europe in the 19th

century was a time of dramatic changes political, economic, and

social. Industrialization created fantastic wealth disparities

and entirely new classes of people as the old aristocratic power

system transformed into a plutocratic one. Cities grew rapidly

and traditional agrarian lifestyles were decimated in favor of

the cramped urban life of wage slavery. Imperial Russia

experienced many of these difficult changes but events often

took on a more extreme character than that of Western Europe and

social development for Russia has always been both painful and

slow.

All of the wiser Russian

monarchs realized that their system of serfdom, with a social

structure of the very few existing on the backs of the very

many, was not sustainable and would end in bloody rebellion

sooner or later. The problem was

implementing reforms that were both effective and politically

realistic. But by the middle of the 19th century the

forces of state repression coupled with the longevity of the

problem had already created such an intolerable situation that

fixing the system through reform was essentially impossible. The

only reasonable answer to this kind of situation is that of

nihilism, the only way to live was to destroy. Russia had become

a stifling, backwards country run by a ruling elite grown

fabulously wealthy through rampant natural resource extraction.

The Russian government had become completely disconnected from

its subjects and new information and new ideas were impossible

to prevent from seeping into the country from the heated and

bubbling social scene in Western Europe. Even a brutal and

violent police-state could not stop the Nihilists, other

dedicated revolutionaries, or the inevitable outcome of the

conflict.

|

Jewel

encrusted Fabergé eggs were an emblematic expression of

late 19thcentury Imperial Russian wealth and a

grossly distorted society where the monarchy could

commission

dozens of these eggs while the general public worked and

starved to death.

|

The heart of

Russian Nihilism was about breaking with the failures of the

past and about crafting a new identity. This was the meaning of

the ‘Fathers and Sons’ phrase used at the time and remembered

today in Turgenev’s novel of the same name.

Whereas the "fathers" grew

up on German idealistic philosophy and romanticism in general,

with its emphasis on the metaphysical, religious, aesthetic,

and historical approaches to reality, the "sons," led by such

young radicals as Nicholas Chernyshevsky, Nicholas Dobroliubov,

and Dmitrii Pisarev, hoisted the banner of utilitarianism,

positivism, materialism, and especially "realism." "Nihilism"

— and also in large part "realism," particularly "critical

realism" — meant above all else a fundamental rebellion

against accepted values and standards: against abstract

thought and family control, against lyric poetry and school

discipline, against religion and rhetoric. The earnest young

men and women of the 1860's wanted to cut through every polite

veneer, to get rid of all conventional sham, to get to the

bottom of things. What they usually considered real and

worthwhile included the natural and physical sciences — for

that was the age when science came to be greatly admired in

the Western world — simple and sincere human relations, and a

society based on knowledge and reason rather than ignorance,

prejudice, exploitation, and oppression.

[1]

This was

about the destruction of idols, about burning the dead wood of

society. And the Russian Nihilists were quite revolutionary

especially given the context of the time and location they

existed in for they include sections of the population that had

little if any representation before. Women for example played a

key role and included some of the most motivated and charismatic

characters of the time period like Vera Figner and Sophia

Perovskaia. “If the

feminists wanted to change pieces of the world, the nihilists

wanted to change the world itself, though not necessarily

through political action.”

[3] The Russian word for a female nihilist is nigilistka.

It’s

important to point out that the nihilist ethos of the time was

primarily individualistic and not always politically

revolutionary; some radical nihilist attitudes precluded

ideological or political orientation. “While

nihilism emancipated the young Russian radicals from any

allegiance to the established order, it was, to repeat a point,

individual rather than social by its very nature and lacked a

positive program — both Pisarev and Turgenev's hero Bazarov died

young.”

[7] Clothing, attitude, communications style, all were portions

of the new nihilist outlook. The clothing style sought

functionality and usefulness over frivolous fashion. The ‘revolt

in the dress’ of the nigilistka went something like this:

One of the most interesting

and widely remarked features of the nigilistka was her

personal appearance. Discarding the "muslin, ribbons,

feathers, parasols, and flowers" of the Russian lady, the

archetypical girl of the nihilist persuasion in the 1860's

wore a plain dark woolen dress, which fell straight and loose

from the waist with white cuffs and collar as the only

embellishments. The hair was cut short and worn straight, and

the wearer frequently assumed dark glasses.

[4]

Nigilistka

fashion was about more than just juvenile rebellion against

bourgeoisie fashion because instead of simply contradicting

established forms it went on to create its own identity. The

reasoning behind much of this was about self-empowerment.

“The

machinery of sexual attraction through outward appearance that

led into slavery was discarded by the new woman whose nihilist

creed taught her that she must make her way with knowledge and

action rather than feminine wiles.”

[4] Even deeper than changes in superficial appearance existed a

new and quite profound realization, for the nigilistka

understood that life had to be defined internally and not solely

by external authorities or values. "To

establish her identity, she needed a cause or a "path," rather

than just a man.”

[4] An interesting departure also occurred in communications

style. “The typical

nigilistka, like her male comrade, rejected the conventional

hypocrisy of interpersonal relations and tended to be direct to

the point of rudeness…”

[4]

Severe times

call for severe measures

Seeing their

efforts at social change only being met with police brutality

and increasing repression by despotic authority, the

revolutionaries reassessed their tactics. Peter Tkachev and

Sergei Nechayev were two that felt

severe times call for severe

measures – the revolution was only getting started.

Several

years of revolutionary conspiracy, terrorism, and

assassination ensued. The first instances of violence occurred

more or less spontaneously, sometimes as countermeasures

against brutal police officials. Thus, early in 1878 Vera

Zasulich shot and wounded the military governor of St.

Petersburg, General Theodore Trepov, who had ordered a

political prisoner to be flogged; a jury failed to convict

her, with the result that political cases were withdrawn from

regular judicial procedure. But before long an organization

emerged which consciously put terrorism at the center of its

activity. The conspiratorial revolutionary society "Land and

Freedom," founded in 1876, split in 1879 into two groups: the

"Black Partition," or "Total Land Repartition," which

emphasized gradualism and propaganda, and the "Will of the

People" which mounted an all-out terroristic offensive against

the government. Members of the "Will of the People" believed

that, because of the highly centralized nature of the Russian

state, a few assassinations could do tremendous damage to the

regime, as well as provide the requisite political instruction

for the educated society and the masses. They selected the

emperor, Alexander II, as their chief target and condemned him

to death. What followed has been described as an "emperor

hunt" and in certain ways it defies imagination. The Executive

Committee of the "Will of the People" included only about

thirty men and women, led by such persons as Andrew Zheliabov

who came from the serfs and Sophia Perovskaia who came from

Russia's highest administrative class, but it fought the

Russian Empire. [6]

After the assassination for the tsar, some began to question the

strategic usefulness of the spiraling violence but few

alternates existed in the oppressive milieu of Imperial Russia.

Subsequent monarchs Alexander III and Nicholas II only became

more reactionary and narrow-minded while simultaneously voiding

even minimal public freedoms. "Murder and the gibbet captivated the

imagination of our young people; and the weaker their nerves and

the more oppressive their surroundings, the greater was their

sense of exaltation at the thought of revolutionary terror.”

– Vera Figner [5]

[B]

[B] |

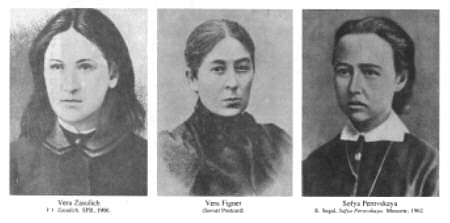

Vera

Zasulich , Vera Figner, and Sophia Perovskaia

"Perovskaya

and her comrades represent a unique phenomenon in

nineteenth-century European social history." [8] |

The Russian

Nihilists were smart, dedicated, and possessed a tenacity that

was unparalleled. These were revolutionaries that were well

aware of the nature of the political system they were in

conflict with but nonetheless they still failed to acquire two

critical elements. Since they had no cohesive, constructive

social program the nihilists lacked strategic sustainability of

their revolutionary movement. Although they achieved their

tactical goal of assassinating the top-level authority figures

their wider objective of gaining greater freedom of movement and

ideas still remained elusive. It seems that the necessary

time-scale of their struggle was longer then anticipated and the

entrenched nature of the system and the culture of fear and

subservience to autocratic rulers that it rested upon was much

deeper than realized; 1000 years of tradition simply can’t be

thrown out in a decade.

But since the social program is secondary to immediate plans

in a larger sense I think the primary problem affecting

the 19th century Russian revolutionaries had more to

do with communications limitations than anything else because

they had most everything going for them except numbers. Lacking

the ability to reach the Russian public except on the smallest

scale made widespread, coordinated revolt practically

impossible. Publishing technology was easy for despotic regimes

to control while radio and cheap printing didn't arrive in

widespread use until the early 20th century.

Although the

political violence may have had questionable strategic value the

cultural shift in views, attitudes, and ideas made significant

contributions that lasted long after the Russian Nihilists

themselves had left the scene. 06.12.03

Such were the true nihilists, the

destroyers, who did not trouble themselves about what was to

be built after them. They did not exactly deny everything, for

they believed firmly, fanatically, in science and in the power

of the individual mind. But they thought nothing else worth

the slightest respect, and they attacked and sneered at

family, religion, art, and social institutions, with all the

more vehemence the higher they were held in the opinion of

their countrymen.

- Sergius Stepniak,

from: Sergius Stepniak on Nihilism and Narodnichestvo

[Extracted from Sergius Stepniak, "Nihilism" in The Great

Events by Famous Historians, vol. 19 (n.p.: The National

Alumni, 1914), pp. 71-85]

References

A) A History of

Russia, sixth edition, by Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, Oxford

University Press 2000.

B) The

Women’s Liberation Movement in Russia – Feminism, Nihilism,

and Bolshevism 1860-1930, by Richard Stites, Princeton

University Press, 1978.

- Reference

A pg.

381

- Reference

B pg.

99-100

- Reference

B pg. 101

- Reference

B pg. 104

- Reference

B pg. 146

- Reference

A pg. 384

- Reference

A pg. 448

- Reference

B pg. 153

Nechayev's Catechism

There are notable

differences between the cultural and political

situation of late 19th century Europe and our 21st

century world. The weight of oppressive authority

is no where near as crushing today as then, especially in comparison to Tsarist Russia. The

situation for the masses was so bleak as to make

death through violence more attractive than life

in slavery; America is no Palestine and

California is no West Bank, if you know what I

mean.

The severity of

revolutionary action has to be matched to the

lack of freedom to express dissenting ideas

within the region of operations. Otherwise you'll

just be blown out of the water by public

rejection and police reaction. Fortunately, today

we have many (peaceful) tools they did not.

Sergei Nechayev's

tenacity was admirable and his methodology scores

points for attempting to address more than merely

the physical infrastructure so typical of Marxism

and other one dimensional "revolutions".

And if nothing else, 'The Catechism' certainly

stirred up debate and generated enthusiasm for

the revolutionary effort. - Freydis 17.05.02

From 'Catechism of a

Revolutionist' (1869)

By Sergei Nechayev

* * *

PRINCIPLES

BY WHICH THE REVOLUTIONARY MUST BE GUIDED IN THE

ATTITUDE OF THE REVOLUTIONARY TOWARDS HIMSELF

1. The revolutionary

is a dedicated man. He has no interests of his

own, no affairs, no feelings, no attachments, no

belongings, not even a name. Everything in him is

absorbed by a single exclusive interest, a single

thought, a single passion - the revolution.

2. In the very

depths of his being, not only in words but also

in deeds, he has broken every tie with the civil

order and the entire cultivated world, with all

its laws, proprieties, social conventions and its

ethical rules. He is an implacable enemy of this

world, and if he continues to live in it, that is

only to destroy it more effectively.

3. The revolutionary

despises all doctrinarism and has rejected the

mundane sciences, leaving them to future

generations. He knows of only one science, the

science of destruction. To this end, and this end

alone, he will study mechanics, physics,

chemistry, and perhaps medicine. To this end he

will study day and night the living science:

people, their characters and circumstances and

all the features of the present social order at

all possible levels. His sole and constant object

is the immediate destruction of this vile order.

4. He despises

public opinion. He despises and abhors the

existing social ethic in all its manifestations

and expressions. For him, everything is moral

which assists the triumph of revolution. Immoral

and criminal is everything which stands in its

way.

5. The revolutionary

is a dedicated man, merciless towards the state

and towards the whole of educated and privileged

society in general; and he must expect no mercy

from them either. Between him and them there

exists, declared or undeclared, an unceasing and

irreconcilable war for life and death. He must

discipline himself to endure torture.

6. Hard towards

himself, he must be hard towards others also. All

the tender and effeminate emotions of kinship,

friendship, love, gratitude and even honor must

be stifled in him by a cold and single-minded

passion for the revolutionary cause. There exists

for him only one delight, one consolation, one

reward and one gratification - the success of the

revolution. Night and day he must have but one

thought, one aim - merciless destruction. In cold-blooded

and tireless pursuit of this aim, he must be

prepared both to die himself and to destroy with

his own hands everything that stands in the way

of its achievement.

7. The nature of the

true revolutionary has no place for any

romanticism, any sentimentality, rapture or

enthusiasm. It has no place either for personal

hatred or vengeance. The revolutionary passion,

which in him becomes a habitual state of mind,

must at every moment be combined with cold

calculation. Always and everywhere he must be not

what the promptings of his personal inclinations

would have him be, but what the general interest

of the revolution prescribes.

THE

ATTITUDE OF THE REVOLUTIONARY TOWARDS HIS

COMRADES IN REVOLUTION

8. The revolutionary

considers his friend and holds dear only a person

who has shown himself in practice to be as much a

revolutionary as he himself. The extent of his

friendship, devotion and other obligations

towards his comrade is determined only by their

degree of usefulness in the practical work of

total revolutionary destruction.

9. The need for

solidarity among revolutionaries is self-evident.

In it lies the whole strength of revolutionary

work. Revolutionary comrades who possess the same

degree of revolutionary understanding and passion

should, as far as possible, discuss all important

matters together and come to unanimous decisions.

But in implementing a plan decided upon in this

manner, each man should as far as possible rely

on himself. In performing a series of destructive

actions each man must act for himself and have

recourse to the advice and help of his comrades

only if this is necessary for the success of the

plan.

10. Each comrade

should have under him several revolutionaries of

the second or third category, that is, comrades

who are not completely initiated. He should

regard them as portions of a common fund of

revolutionary capital, placed at his disposal. He

should expend his portion of the capital

economically, always attempting to derive the

utmost possible benefit from it.

Himself he should

regard as capital consecrated to the triumph of

the revolutionary cause; but as capital which he

may not dispose of independently without the

consent of the entire company of the fully

initiated comrades.

11. When a comrade

gets into trouble, the revolutionary, in deciding

whether he should be rescued or not, must think

not in terms of his personal feelings but only of

the good of the revolutionary cause.

Therefore he must

balance, on the one hand, the usefulness of the

comrade, and on the other, the amount of

revolutionary energy that would necessarily be

expended on his deliverance, and must settle for

whichever is the weightier consideration.

THE

ATTITUDE OF THE REVOLUTIONARY TOWARDS SOCIETY

12. The admission of

a new member, who has proved himself not by words

but by deeds, may be decided upon only by

unanimous agreement.

13. The

revolutionary enters into the world of the state,

of class and of so-called culture, and lives in

it only because he has faith in its speedy and

total destruction.

He is not a

revolutionary if he feels pity for anything in

this world. If he is able to, he must face the

annihilation of a situation, of a relationship or

of any person who is part of this world -

everything and everyone must be equally odious to

him. All the worse for him if he has family,

friends and loved ones in this world; he is no

revolutionary if he can stay his hand.

14. Aiming at

merciless destruction the revolutionary can and

sometimes even must live within society while

pretending to be quite other than what he is. The

revolutionary must penetrate everywhere, among

all the lowest and the middle classes, into the

houses of commerce, the church, the mansions of

the rich, the world of the bureaucracy, the

military and of literature, the Third Section [Secret

Police] and even the Winter Palace.

15. All of this

putrid society must be split up into several

categories: the first category comprises those to

be condemned immediately to death. The society

should compose a list of these condemned persons

in order of the relative harm they may do to the

successful progress of the revolutionary cause,

and thus in order of their removal.

16. In compiling

these lists and deciding the order referred to

above, the guiding principal must not be the

individual acts of villainy committed by the

person, nor even by the hatred he provokes among

the society or the people. This villainy and

hatred, however, may to a certain extent be

useful, since they help to incite popular

rebellion. The guiding principle must be the

measure of service the person’s death will

necessarily render to the revolutionary cause.

Therefore, in the

first instance all those must be annihilated who

are especially harmful to the revolutionary

organization, and whose sudden and violent deaths

will also inspire the greatest fear in the

government and, by depriving it of its cleverest

and most energetic figures, will shatter its

strength.

17. The second

category must consist of those who are granted

temporary respite to live, solely in order that

their goofy behavior shall drive the people to

inevitable revolt.

18. To the third

category belong a multitude of high-ranking

cattle, or personages distinguished neither for

any particular intelligence no for energy, but

who, because of their position, enjoy wealth,

connections, influence and power. They must be

exploited in every possible fashion and way; they

must be enmeshed and confused, and, when we have

found out as much as we can about their dirty

secrets, we must make them our beasts of burden,

as if they were but mere oxen of the field. Their

power, connections, influence, gold and energy

thus become an inexhaustible treasure-house and

an effective aid to our various enterprises.

19. The fourth

category consists of politically ambitious

persons and liberals of various hues. With them

we can conspire according to their own programs,

pretending that we are blindly following them,

while in fact we are taking control of them,

rooting out all their secrets and compromising

them to the utmost, so that they are irreversibly

implicated and can be employed to create disorder

in the state.

20. The fifth

category is comprised of doctrinaires,

conspirators, revolutionaries, all those who are

given to drunken bullshitting, whether before

audiences or on paper. They must be continually

incited and forced into making violent

declarations of practical intent, as a result of

which the majority will vanish without trace and

real revolutionary gain will accrue from a few.

21. The sixth, and

an important category is that of women. They

should be divided into three main types: first,

those frivolous, thoughtless, and fluff-headed

women who we may use as we use the third and

fourth categories of men; second, women who are

ardent, gifted, and devoted, but do not belong to

us because they have not yet achieved a real,

passionless, and practical revolutionary

understanding: these must be used like the men of

the fifth category; and, finally there are the

women who are with us completely, that is, who

have been fully initiated and have accepted our

program in its entirety. We should regard these

women as the most valuable of our treasures,

whose assistance we cannot do without.

THE

ATTITUDE OF OUR SOCIETY TOWARDS THE PEOPLE

22. Our society has

only one aim - the total emancipation and

happiness of the people, that is, the common

laborers. But, convinced that their emancipation

and the achievement of this happiness can be

realized only by means of an all-destroying

popular revolution, our society will employ all

its power and all its resources in order to

promote an intensification and an increase I

those calamities and horrors which must finally

exhaust the patience of the people and drive it

to a popular uprising.

23. By “popular

revolution” our society does not mean a

regulated movement on the classical French model

- a movement which has always been restrained by

the notion of property and the traditional social

order of our so-called civilization and morality,

which has until now always confined itself to the

overthrow of one political structure merely to

substitute another, and has striven thus to

create the so-called revolutionary state. The

only revolution that can save the people is one

that eradicates the entire state system and

exterminates all state traditions of the regime

and classes on Earth.

24. Therefore our

society does not intend to impose on the people

any organization from above. Any future

organization will undoubtedly take shape through

the movement and life of our people, but that is

a task for future generations. Our task is

terrible, total, universal, merciless destruction.

25. Therefore, in

drawing closer to the people, we must ally

ourselves above all with those elements of the

popular life which, ever since the very

foundation of the state power of Moscow, have

never ceased to protest, not only in words but in

deeds, against everything directly or indirectly

connected with the state: against the nobility,

against the bureaucracy, against the priests,

against the world of the merchant guilds, and

against the tight-fisted hillbilly land pirate.

But we shall ally ourselves with the intrepid

world of brigands, who are the only true

revolutionaries in Russia.

26. To knit this

world into a single invincible and all-destroying

force - that is the purpose of our entire

organization, our conspiracy, and our task.

Notes:

Original source unknown.

Electronic editing of the 'Catechism' provided by kampahana;

formatting and condensation done by Freydis, 2002.

Atheist

Manifesto

It is hard to

say when human thought first conceived of the existence of God.

But once having conceived of him, it proceeded to reject him.

Possibly the rejection of God occurred immediately after the

first conception of him, the first recognition of his existence.

In any event, the rejection of God is very old, and the seeds of

unbelief appeared very early in the history of mankind. In the

course of several centuries, however, these modest seeds of

atheism were strangled by the poisonous nettles of theism. But

the striving of human thought and feeling for freedom is too

great not to prevail. And it has indeed prevailed. Beneath its

pressures all religions have broadened their horizons, yielding

one point after another and casting off much that only a

generation ago was deemed indispensable. Religion, striving to

preserve its existence, has made various compromises, piling one

absurdity upon another, combining the uncombinable.

The naive legends concerning

the origins of the earth, legends created by pastoral folk at

the dawn of life, were cast off and relegated to the mythology

of 'holy books'. Beneath the pressure of science, religion

repudiated the Devil and repudiated the personification of the

deity. Instead, God now reveals himself to us as Reason,

Justice, Love, Mercy, etc., etc. Since it was impossible to

salvage the contents of religion, men preserved its forms,

knowing full well that the forms would give shape to whatever

contents were placed in them.

The whole

so-called progress of religion is nothing but a series of

concessions to emancipated will, thought and feeling. Without

their persistent attacks, religion would to this day preserve

its original crude and naive character. Thought, moreover,

achieved other triumphs as well. Not only did it compel religion

to become more progressive, or, more accurately, to give birth

to new forms, but it also took an independent creative step,

moving ever more boldly towards open, militant atheism.

And our

atheism is militant atheism. We believe it is time to begin an

open, ruthless struggle with all religious dogmas, whatever they

may be called, whatever philosophical or moral systems may

conceal their religious essence. We shall fight against all

attempts to reform religion or to smuggle the outmoded concepts

of past ages into the spiritual baggage of contemporary

humanity. We find all gods equally repulsive, whether blood

thirsty or humane, envious or kind, vengeful or forgiving. What

is important is not what sort of gods they are but simply that

they are gods — that is, our lords, our sovereigns — and that we

love our spiritual freedom too dearly to bow before them.

Therefore we

are atheists. We shall boldly carry our propaganda of atheism to

the toiling masses, for whom atheism is more necessary than

anyone else. We fear not the reproach that by destroying the

people's faith we are pulling the moral foundation from under

their feet, a reproach uttered by 'lovers of the people' who

maintain that religion and morality are inseparable. We assert,

rather, that morality can and must be free from any ties with

religion, basing our conviction on the teachings of contemporary

science about morality and society. Only by destroying the old

religious dogmas can we accomplish the great positive task of

liberating thought and feeling from their old and rusty fetters.

And what can better break such bonds?

We hold that

there are no objective ideas either in the existing universe or

in the past history of peoples. An objective world is nonsense.

Desires and aspirations belong only to the individual

personality, and we place the free individual in the main

corner. We shall destroy the old, repulsive morality of religion

which declares: 'Do good or God will punish you.' We oppose this

bargaining and say: 'Do what you think is good without making

deals with anyone but only because it is good.' Is this really

only destructive work?

So much do we

love the human personality that we must therefore hate gods. And

therefore we are atheists. The age—old and difficult struggle of

the workers for the liberation of labour may continue even

longer. The workers may have to toil even more than they already

have, and to sacrifice their blood in order to consolidate what

has already been won. Along the way, the workers will doubtless

experience further defeats and, even worse, disillusionment. For

this very reason they must have an iron heart and a mighty

spirit which can withstand the blows of fate. But can a slave

really have an iron heart? Under God all men are slaves and

nonentities. And can men possess a mighty spirit when they fall

on their knees and prostrate themselves, as do the faithful?

We shall

therefore go to the workers and try to destroy the vestiges of

their faith in God. We shall teach them to stand proud and

upright as befits free men. We shall teach them to seek help

only from themselves, in their own spirit and in the strength of

free organizations. We are slandered with the charge that all

our best feelings, thoughts, desires and acts are not our own,

are not experienced by us, but are God's, are determined by God,

and that we are not ourselves but a mere vehicle carrying out

the will of God or the Devil. We want to take responsibility for

everything upon ourselves. We want to be free. We do not want to

be marionettes or puppets. Therefore we are atheists.

Religions

recognize their inability to sustain man's belief in the Devil,

and are rejecting that already discredited figure. But this is

inconsistent, for the Devil has as much claim to existence as

God — that is, none at all. Belief in the Devil was once very

strong. There was a time when demonism held exclusive sway over

men's minds, yet now this menacing figure and tempter of

humanity has been transformed into a petty demon, more comical

than frightening. The same fate must likewise befall his blood-brother — God.

God, the

Devil, faith — mankind has paid for these awful words with a sea

of blood, a river of tears, and endless suffering. Enough of

this nightmare! Man must finally throw off the yoke, must become

free. Sooner or later labour will win. But man must enter the

society of equality, brother hood and freedom ready and

spiritually free, or at least free of the divine rubbish which

has clung to him for a thousand years. We have shaken this

poisonous dust from our feet, and we are therefore atheists.

Come with us

all who love man and freedom and hate gods and slavery. Yes, the

gods are dying! Long live man! -

Union of Atheists

Original

source: Soiuz Ateistov, 'Ateisticheskii manifest', Nabat

(Kharkov),12 May 1919, p. 3.

Via:

The

Anarchists in the Russian Revolution, edited by Paul Avrich,

Cornell University Press 1973.

Michael Bakunin: "Founder of Nihilism

and apostle of anarchy." - Herzen

Michael

Bakunin was born in 1814 and came from a large wealthy

family in Russia. Even from an early age Bakunin’s rebellious

personal nature and outlook set him at odds against the ruling

class he emerged from although at the same time he never truly

identified with the proletarian masses either.

Bakunin wanted

action, he placed movement over passive thought but this was his

charm because he meshed so well with the revolutionary milieu of

his era. In another time or place Bakunin would have been simply

written off as a fringe element but because of the

rapidly changing social and political landscape of the 19th

century he became an icon and a legend. Rumor and myth about his

escapes from the secret police and his own talk of direct action

created an aura of the superhuman revolutionary, fulfilling the

eras need for a leader and hero even if his actual deeds failed

to fulfill the myths around him. Bakunin wanted

action, he placed movement over passive thought but this was his

charm because he meshed so well with the revolutionary milieu of

his era. In another time or place Bakunin would have been simply

written off as a fringe element but because of the

rapidly changing social and political landscape of the 19th

century he became an icon and a legend. Rumor and myth about his

escapes from the secret police and his own talk of direct action

created an aura of the superhuman revolutionary, fulfilling the

eras need for a leader and hero even if his actual deeds failed

to fulfill the myths around him.

Bakunin’s

Philosophy

Even at the

time Bakunin was often difficult to describe and even more

difficult to categorize ideologically within the context of his

contemporaries, revolutionaries and other great-thinkers of the

19th century. Bakunin gained from process rather than

accomplishment in life, whether the process had aim or not

wasn’t so much the issue as the act itself,

“finished

things were a source of weariness to him”

[Lampert (1957), pg 123]

Bakunin never really connected with any of the ideologies of his

time, he just saw opportunities either for his own advancement

or the pure, ground-up revolution he desired to see happen.

Destruction, action and revolution as a way of life were primary

themes that emerged. Bakunin went so far as to define

destruction as the moving force of

history. Simple but powerful statements were typical of Bakunin

and indeed this was the appeal.

Keeping with

the destruction paradigm, Bakunin’s analysis of Hegel was

remarkable. “Bakunin

argues that the dialectic refutes both those whose ideal is in

the past (primitive wholeness, as the dialectical source of the

divisions of the present, can never be regained), and those who

seek a middle way between extremes. No compromise is possible:

'the whole essence, content, and vitality of the negative

consists in destruction of the positive': only thereby can

divisions be resolved in a 'new, affirmative, organic reality’.”

[Kelly (1987), pg. 93-94]

Organizing

and Direct Action

Bakunin had

little interest in the nuances and details of revolutionary and

political organizing because he thought they only contained his

energy rather than magnified it and also because he couldn’t

focus or stay on task long enough to take an organization

towards a goal. Bakunin was no Lenin. But that doesn’t mean he

didn’t try to organize a revolution and then try again because

he always wanted to see the revolution happen before his eyes

even if he had no idea how to actually carry it out! Bakunin

lacked planning and organizing skills as much as he had a

surfeit of revolutionary zeal and a limitless capacity for

making motivating speeches.

After many

false starts Bakunin finally found the action he wanted in

Dresden in May of 1849 where he ingratiated himself into the

local resistance and fought Prussian troops. But despite best

efforts the rebel forces were hopelessly outnumbered and

eventually the Saxon government arrested Bakunin. After being

transferred from one prison to another the governments finally

came to an agreement and Bakunin was shipped off to the dreaded

Peter and Paul fortress in Russia. Bakunin was imprisoned and

later exiled to Siberia for ten years. A long prison sentence

broke him physically but not mentally.

After an

amazing confluence of chance and opportunity in 1861, Bakunin

managed to escape on a ship to Japan and then to San Francisco

eventually ending up back in Europe. Bakunin went back to what

he did best – trying to stir up revolutionary action, somewhere,

anywhere even if more than before his long imprisonment he

lacked any substantive connections to the real revolutionary

planning on the streets.

Nechayev and

Bakunin

In 1869 a

mysterious Russian named Sergei Nechayev met with Michael

Bakunin. The two immediately found a use for each other amid

their collective desire to foment revolution inside Russia – a

daunting task that had so far eluded the best of Bakunin’s

efforts. But Nechayev was a very crafty man and Bakunin was

often naïve and trusting, blinded by his own enthusiasm -

trouble emerged. Nechayev for his part probably never had any

delusions as to his own aim and kept silent letting Bakunin do

the talking.

Nechayev and

Bakunin seemed to complement each other in attributes, one was a

great speaker, the other not, one a formidable plotter where the

other wasn’t, but in the end Nechayev’s selfish view on

revolution coupled with Bakunin’s gullibility led to a falling

out and the two departed on unfriendly terms without notable

revolutionary success but still attracting the concerted

attention of the secret police.

Marx versus

Bakunin

Trying

to fit Bakunin into the larger scheme of political philosophy is

challenging because he wrote very little and his own views were

often a confusing mix of other’s ideas and his own

interpretations. A comparison of Karl Marx and Michael Bakunin

is interesting in the very different path two thinkers with

differing personalities took in analyzing and attempting to

solve the problems of their day and to then direct it into

revolutionary action. Bakunin was not a theorist or a planner

like Marx, rather he was a promoter of the process of action

even regardless of the outcome or eventual effect.

“He was by nature a

solipsist, despite all his superficial gregariousness and his

later advocacy of anti-individualist anarchism, and the world

existed for him for the exercise of personal freedom and

creative action.” [Lampert (1957),

pg. 123]

Atheism

Although he may have had

private discussions that placed him more in the agnostic

category, his public message was a consistent one of staunch

atheism once asserting that "If

God really existed it would be necessary to abolish him.”

Bakunin’s individualist credo also influenced the Russian

anarchists that followed him as well as more modern forms of

individual, libertarian anarchism. Bakunin died in 1876 but the

revolution continued. His primary surviving work is the book

God and the State, a potent patchwork of ideas and musings

on history, revolution, religion and authority.

Further

Influence

Although his direct involvement in

revolutionary activities was limited, Bakunin had a much greater

impact on contemporary and even future ideas. Bakunin’s

destructive words influenced the Nihilists in the 1860s

characterized by the clean-sweep revolution.

“…the modern

rebels believe, as Bazarov and Pisarev and Bakunin believed,

that the first requirement is the clean sweep, the total

destruction of the present system; the rest is not their

business. The future must look after itself. Better anarchy than

prison; there is nothing in between.”

[Berlin, p. 301] And despite

Bakunin’s organizing faults it’s agreed that he was actually a

generous and very friendly person and for all his exhortations

to violence like his most famous maxim

“The

urge to destroy is also a creative urge”,

it was not

the people he was targeting so much as the actual institutions of

oppression.

-

October, 2004

References

-

-

-

-

-

-

Riasanovsky,

Nicholas V., A History of Russia, New York,

Oxford University Press, sixth edition, 2000.

|