^

Died on 07 September

1910: William Holman Hunt,

Londoner Pre-Raphaelite

painter born on 02 April 1827. — Not to be confused with US painter

William Morris Hunt [31 March 1824 – 08

September 1879]

— William Holman Hunt was born in London. A clerk for several years,

he left the world of trade to study at the British Museum and the National

Gallery. In 1844 he entered the Royal Academy. Here he joined with Millais

and Rossetti to develop the Pre-Raphaelite theories of art and, in 1848,

to found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His first painting to interpret

these themes was Rienzi, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849.

In 1854 Hunt went to the Holy Land to portray scenes from the life of Christ,

aiming to achieve total historical and archaelogical truth. He returned

to Palestine in 1869 and again in 1873. Throughout his life Hunt remained

dedicated to Pre-Raphaelite concepts, as exemplified in such works as The

Light of the World, The Scapegoat and The Shadow of Death.

Hunt died in Kensington, London.

— Hunt worked as an office clerk in London from 1839 to 1843, attending

drawing classes at a mechanics’ institute in the evenings and taking weekly

lessons from the portrait painter Henry Rogers. Holman Hunt overcame parental

opposition to his choice of career in 1843, and this determined attitude

and dedication to art could be seen throughout his working life. In July

1844, at the third attempt, he entered the Royal Academy Schools. His earliest

exhibited works, such as Little Nell and her Grandfather (1846),

reveal few traces of originality, but the reading of John Ruskin’s Modern

Painters in 1847 was of crucial importance to Holman Hunt’s artistic

development. It led him to abandon the ambitious Christ and the Two

Marys in early 1848, when he realized its traditional iconography would

leave his contemporaries unmoved. His next major work, The Flight of

Madeline and Porphyro during the Drunkenness Attending the Revelry

(1848), from John Keats’s Eve of Saint Agnes, though displaced

into a medieval setting, dramatized an issue dear to contemporary poets

and central to Holman Hunt’s art: love and youthful idealism versus loyalty

to one’s family. His first mature painting, it focuses on a moment of psychological

crisis in a cramped and shallow picture space. The Keatsian source, rich

colors and compositional format attracted the attention of Dante Gabriel

Rossetti, leading to his friendship with Holman Hunt and thus contributing

to the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the autumn of 1848.

— In 1844, Hunt was admitted as a student to the Royal Academy, where

he met John

Millais [08 Jun 1829 – 13 Aug 1896] and Dante

Gabriel Rossetti [12 May 1828 – 09 Apr 1882]. For some time he

shared a studio with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the pair, along with Millais

and a few others, who had a common contempt of contemporary English art

and its academic rules, started the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood, which aimed at restoring English painting to its former

heights. John Ruskin supported the group and supplied a theoretical foundation

for its aims.

Hunt believed that

renewal of art must involve a return to honored religious and moral ideals,

and these became the center of his work. He used biblical subjects; to paint

scenery for these themes he visited Palestine several times, see The

Scapegoat (1856) and The

Finding of Savior in the Temple (1860). He also frequently took

themes from old English myths and sagas, from Shakespeare, and Keats, filling

them with an intense symbolism in which every small detail contributed to

the picture's message and which is not easy to understand to a modern viewer.

The years 1866-1868, he worked in Florence.

At first Victorian England did

not accept his works. Thus The

Awakening Conscience (1853) infuriated the public; it was normal

for a Victorian man to keep a mistress, but nobody spoke about it aloud

and who was this Hunt to accuse others? When the public gradually grew to

accept to Hunt his work was highly regarded. Hunt's series of magazine articles

gathered in the book Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

(1905) is a valuable record of the movement.

— Hunt, a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was born in London,

the son of a warehouse manager. Throughout his life he was a devout Christian.

He was also serious minded, and lacking in a sense of humour. Hunt joined

the Royal Academy Schools in 1844, where he met Millais and Rossetti, and,

in fact brought them together. In 1854 Hunt decided to visit the Holy Land,

to see for himself the genuine background for the religious pictures he

intended to paint. The first tangible results of this journey were two paintings,

The Scapegoat, and The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple,

which was exhibited nationally to great acclaim in 1860, and sold for the

sum of 5,500 guineas, Hunt was advised on the price by Charles Dickens.)

This sale, which included the copyright established the painter both financially,

and artisticly. Hunt’s famous picture The Light of the World, was

one of the greatest Christian images of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Hunt worked at night on this picture, in an unheated shelter in a wood near

Ewell in Surrey.

Hunt did not have the natural talent of Millais,

or the intellect and vision of Rossetti. He made up for this by sheer hard

work and commitment. He could have been a very successful portrait painter

had he chosen to be so. In later years, as his sight started to fail, perhaps,

his colors became increasingly harsh. He was still capable of great things,

however, as shown by his wonderful late picture The Lady of Shallott,

surely one of the most powerful Pre-Raphaelite images. In his last years

Hunt became the patriach of Victorian painting. He was awarded the Order

of Merit by King Edward VII in 1905. Hunt married firstly Fanny Waugh, and

after her death in childbirth her younger sister Edith. He was also a far

more attractive personality than is generally supposed, with a wide range

of interests, which included horse racing and boxing.

— Robert Braithwaite Martineau was a student of Hunt.

— LINKS

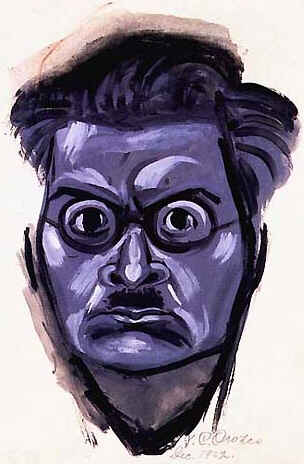

— Self-Portrait

(1845, 46x39cm)

— Isabella,

or the Pot of Basil (1867; 192x91cm) _ This painting

is based on Isabella,

or the Pot of Basil by

John Keats [31 Oct 1795 – 23 Feb 1821].

— May

Morning on Magdalen Tower, Oxford (1890, 155x200cm,

840x1092pix — ZOOM

to 1700x2205pix, 2178kb)

— smaller, very slightly different, version: May

Morning on Magdalen Tower, Oxford (1893, 39x49cm, 931x1177pix,

184kb — or see

the 931x1177pix picture in a 2354x2350pix round frame, 2104kb) _ Following

a custom thought to derive from the ancient druids, a service was held on

the tower of Magdalen College, Oxford, on May Day morning. Choristers and

college staff sang hymns to welcome spring at the break of day. The light

blue sky and pink clouds convey the freshness of the early morning light,

while the abundant flowers remind us of the imminent arrival of summer.

At the far right is an Indian Parsee, or sun-worshipper.

— Dante

Gabriel Rossetti (1883, 30x23cm)

— The

Dead Sea from Siloam (1855, 25x35cm)

— Valentine

Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851)

— The

Light of the World (1853, 126x60cm)

— The

Lady of Shalott (1892) — Shadow

of Death (1873, 93x73cm)

— Il

Dolce Far Niente (1866) — The Lantern

Maker's Courtship (1854)

— The Awakening

Conscience (1853)

— A Converted

British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of

the Druids (1850, 111x141cm)

— The

Scapegoat (1854) — On

English Coasts (1852) _ sheep

— The

Triumph of the Innocents (157x248cm)

— The

Hireling Shepherd (1851, 77x110cm) — Claudio

and Isabella (1853, 78x46cm)

|

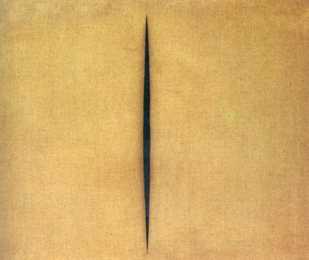

La gran ruptura artística de Lucio Fontana — dicho sea en términos

teóricos y también materiales — ocurre en 1949, cuando empieza a realizar

sus telas con perforaciones (buchi), que serán sucedidas, una década más

tarde, por las telas con tajos (tagli), como en la obra aquí presentada.

Es evidente la naturaleza conceptualista y gestual de estas creaciones de

Fontana — que él llevará además a otros soportes, como el papel y el

metal —, y su sentido estético: al rasgar la tela y quebrar su continuidad,

acaba con la idea que de ella tuvo y tiene la pintura, la de una superficie

ilusoria capaz de albergar una representación ficticia; por lo tanto, recupera

la verdad de esa tela en beneficio de una nueva (forma de) creación. El

tajo, que conecta el anverso y el reverso del lienzo, integra el espacio

real a la obra y abre una vía de comunicación con el infinito, aboliendo

la necesidad de pintar.

La gran ruptura artística de Lucio Fontana — dicho sea en términos

teóricos y también materiales — ocurre en 1949, cuando empieza a realizar

sus telas con perforaciones (buchi), que serán sucedidas, una década más

tarde, por las telas con tajos (tagli), como en la obra aquí presentada.

Es evidente la naturaleza conceptualista y gestual de estas creaciones de

Fontana — que él llevará además a otros soportes, como el papel y el

metal —, y su sentido estético: al rasgar la tela y quebrar su continuidad,

acaba con la idea que de ella tuvo y tiene la pintura, la de una superficie

ilusoria capaz de albergar una representación ficticia; por lo tanto, recupera

la verdad de esa tela en beneficio de una nueva (forma de) creación. El

tajo, que conecta el anverso y el reverso del lienzo, integra el espacio

real a la obra y abre una vía de comunicación con el infinito, aboliendo

la necesidad de pintar.