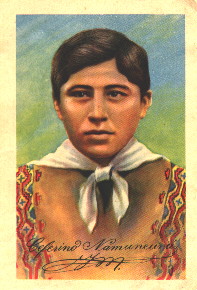

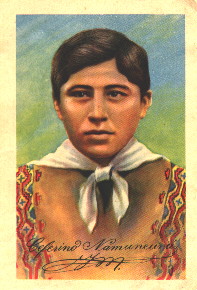

ZEPHERIN NAMUNCURA

|

Zepherin Namuncura was destined by birth to be a “cacique” or leader of his people, the Araucano Indians of the Argentine Pampas. The eighth of twelve children of the chief, Manuel Namuncura, Zepherin was slated -- by virtue of his intelligence and ability -- to be the successor of his father as leader of this fierce, warlike tribe. (The succession was hereditary by family, but did not necessarily fall to the oldest son. However, Zepherin spent his short life training for a different kind of leadership. His ambition was to lead his people to the religion of the one true God.

Shortly before Zepherin’s birth, the Araucano, under the leadership of Manuel Namuncura, had engaged in a last fierce war against the encroaching European colonists. Many atrocities were committed by both sides. At last, the Argentine Minister of War, General Julio Roca, determined to raise a strong army and wipe out the Araucano. In a swift campaign, the army captured two thousand of the Indians, including Manuel Namuncara’s wife and four of his children. Surrender was the Indians’ only alternative to complete destruction.

|

|

Through the arbitration of the one European the cacique would trust, a Salesian priest, a treaty was made, giving the tribe lands and making their chief a colonel in the Argentine army. This treaty was modified in 1894, pushing the Indians further west to worse territory near Alumina, a high valley among the snowy peaks of the Andes mountains.

When Zepherin was two, his father gave him to the Salesian priest, Father Dominic Milanesio, telling him that he was giving this son, the future leader of his people, to be brought up in the white man’s religion. The baby was given the baptismal name of Zepherin in honor of a third century pope -martyr. The name means “wind,” and perhaps the priest hoped that this new leader of the Araucano would be a cooling wind to put out the flames of war in his people.

In 1897, Manuel Namuncura decided to exercise his rights as a colonel in the army and took the eleven-year-old Zepherin to demand his enrollment at the army academy, El Tigre. It was the chief’s wish that there the boy could learn the white man’s military tactics. Unfortunately, as Zepherin was the only Indian child at the school, the other students were cruel in their treatment of him. HE was so unhappy there that he began to lose weight and actually became ill. At the suggestion of Father Dominic, he was moved to the Salesian mission school in Buenos Aires.

At the mission school, Zepherin studied hard, and his grades remained in the top half of the class. Though not particularly bright when it came to books, he was, in the words of his teacher, a “plugger.” Although the schedules and the discipline were hard on a boy used to the freedom of the Indian tribal existence, he felt at home among the students. Asked what he liked best about the school, he replied, “The church and the food” -- although he complained that he couldn’t eat the “bread“ at the altar. At the age of twelve, the “Little Chief” was allowed this Food too.

One day during class, his teacher noticed that Zepherin often appeared to be daydreaming and staring out into the corridor. But despite the fact that the teacher called on him suddenly several times, he could not catch the boy without a ready reply. Later, the teacher moved Zepherin to a new seat where he could not stare off into the corridor. After class, Zepherin asked to be returned to his former place. When asked why, he replied that from his old seat he was able to see the sanctuary lamp burning near Jesus in the chapel. Of course the youth’s request was honored.

Manuel Namuncura

|

A child of the outdoors, Zepherin loved sports. He was a good horseman and an expert archer. His clever hands were often occupied in making bows and arrows for himself and his classmates and sometimes the boys would have archery competitions with “Zeph” as the judge.

One time, when Zepherin’s father, Manuel, came for a visit to his son, he was treated as an honored guest, and the two spent several happy days together. When Manuel left, he gave Zepherin the sum of ten pesos with instructions to use it for a special treat for himself. Like most of the boys at the mission school, Zepherin was poor. His cloths were usually hand-me-down, and ten pesos would buy something quite nice. The priest was surprised when as soon as his father had left, Zepherin brought him the money, telling him to sue it to decorate Our Lady’s alter. The priest protested that the money was intended for Zepherin. In turn, the Little Chief replied that, used for Our Lady, it would indeed be a treat for him. He stated that he wanted Our Lady to become the Queen of his people.

|

Although his outgoing personality and basic honesty made him a favorite at the school, sometimes the boys would unintentionally say things that would hurt Zepherin’s feelings. Once, when a fellow student in a discussion about the Indians asked Zeph what human flesh tasted like, the boy bowed his head and a large tear slipped down his high cheeks. He did not remonstrate with the thoughtless student, however, but simply continued the conversation and ignored the question.

At the time for Zepherin to leave the mission school grew closer, he was asked what he wanted to do. He said that he wanted to become a priest in order to take the true religion to his people, and to open a school for the children of the Araucano. Bishop Cagliero, the Salesian superior, like this sturdy seventeen-year-old, and after warning him that studies for the priesthood would not be easy, arranged for his entrance into the minor seminary at Viedma.

At the seminary, too, Zepherin was well liked. He engaged in sports and small hunting expeditions for recreation, as well as studying hard enough to become second in his class. He enjoyed doing card tricks for his classmates. Zepherin remembered the words of the priest who had come to convert his people: “Serve God with joy.”

In addition to the fun and the learning, Zepherin was growing in virtue. He could often be found in front of the Blessed Sacrament, prying for his people. Little Chief did not forget his Indian origins; he wanted to remain an Indian. A favorite devotion was the Rosary -- also prayed for the benefit of his people. One of his classmates alter said, “During the six months I lived with Namuncura, I saw him relive all the virtues I had read about in the life of Dominic Savio.”

On September 24, 1903, with the permission of his superiors, Zepherin organized a procession in honor of Our Lady of Mercy. That night he fell into bed tired from his day’s labor. He awoke coughing and spitting up blood. The disease that was slowly wiping out his entire tribe had caught up with him: Zepherin had tuberculosis.

On being informed of Namuncura’s condition, the bishop immediately had him sent to the hospital at Viedma. Of his time there, the hospital chaplain said, “Little Chief rarely talked. We often thought he lived in continual prayer. He never gave signs of impatience or disgust. Grateful for any service, he smiled his tanks to all and obeyed every order given him.”

In April of 1904, Pope Pius X appointed Bishop Cagliero archbishop, and summoned him to Rome. The bishop asked Zepherin if he would like to accompany him to Rome and remain there to continue his studies for the priesthood. It was thought that he would thus experience war dry air which might be good for his health.

After a month at sea, the bishop and the young seminarian set foot on European soil. Zepherin was impressed with the strangeness of everything, but the biggest attraction was the large picture of Mary Help of Christians in the basilica at Turin. The picture seemed like a magnet, drawing the young Indian to pray before it for help for his people.

The priest who took care of Zepherin while he was in Turin said, “Every time I looked for him, I found him praying before the picture of Mary Help of Christians.” Asked what he was praying for, the constant reply was, “For my people.”

At Turin, and later in Rome, Zepherin was privileged to have several fortunate experience. He was present for the translation of the remains of St. John Bosco, and in company with Archbishop Cagliero, had a private audience with Pope Pius X. During a large mission exhibit in Turin, a well-dressed lady stopped by Zepherin’s booth. He had dressed in his native costume for the exhibit, and his manners and refinement were impressive to all. The lady asked that he guide her through the rest of the exhibit. Who was she? The Queen of Italy.

At first, Zepherin attended a seminary in Turin. The director said of him, “He has a heart warm with God’s love. It’s a heart of gold, and sees no evil in anyone. It’s a treat to hear him talk about God and Our Lady. He loves God like we love our mothers . . . warmly, intensely, as though he were always in God’s presence.” Unfortunately, the Turin climate was not beneficial to his health, so he was transferred to a seminary just a few miles from Rome.

In March of 1905, Zepherin took a sudden turn for the worse. He lost weight alarmingly, and seemed to be often in pain. Nevertheless, his gentleness and the smile in his eyes never left. His director wrote, “He got worse day by day, yet he was never impatient. He suffered, but he held onto his cross generously.”

In April, Zepherin was transferred to the hospital run by the Brothers of God in Rome. Here he bore his cross of suffering heroically, constantly praying the Rosary for his people. He died on the morning of May 11, surrounded by several of the brothers who were praying for him. He was buried in Rome, but at the insistence of his people, his body was taken back to Patagonia in 1924 and buried at the Salesian school of Fortin Mercedes. Zepherin was declared Venerable by Pope Paul VI in 1972.

from Modern Saints; their Lives and Faces. Book One. By Ann Ball. TAN Books, Rockford Illinois, 1983

Venerable Ceferino Namuncura Home Page