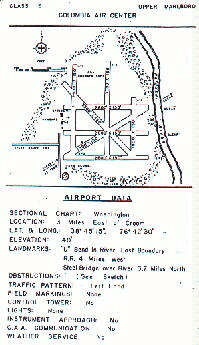

Drive south past Upper Marlboro, Maryland, turn left at

route 382, about four miles south of the intersection of

Pennsylvania Avenue and route 301. Another three miles and turn

left at Croom Airport Road. It is three miles to the site, but

be careful. The road takes a sharp right turn after 1.3 miles.

When you reach the end, there's not much to see.

Columbia Air Center at Croom, Maryland, is unique in Black history. You might rate this accomplishment right up there with Charles Lindbergh's flight when you consider the amount of determination and courage it took.

Many stumbling blocks were maliciously placed in their way by bad men filled with deep hatred. But you can not bury the dreams of people determined to make something for themselves, despite artificial barriers.

Those magnificent aviators at the Columbia Air Center, Croom, Maryland, were people who set an excellent example for today's young people. They taught an enduring lesson. It is simple. You must overcome adversity through love and determination.

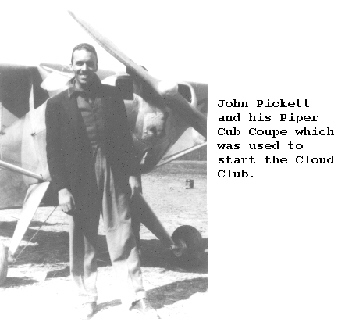

This story started May 1, 1940, when a group of African-American men incorporated the Cloud Club in Washington, D.C. They began flying at Beacon Field, Alexandria, in their own airplane, a 1939 Piper Cub Coupe.

Cloud Club consisted of Harold Smith, president, Roland

Brawner, vice president, John Pinkett, treasurer, and members

Alvin Barnes, Andrew Martin, David Peter, and Charles Ware.

Things did not go smoothly for John Pinkett and the Cloud Club in Alexandria, Virginia. Very soon they were accused of violating airfield rules. Management at Beacon Field gave the Cloud Club a message loud and clear, "We don't want your kind here. Find someplace else."

Well, they did find someplace else, a 450 acre potato field near Croom, Maryland.

The Cloud Club leased the potato field for fifty dollars a month from Rebecca Fisher. The first flight from Croom Field is noted in the logbook of a student pilot, William H. Rhodes on February 22, 1941. Pilot and mechanic John W. Greene, Jr., was the manager.

The Washington Afro-American newspaper wrote August 16, 1941, ". . .(Croom is) the only field solely operated by a colored staff."

Fred Pitcher is the only graduate to have a successful career as an airline pilot. He learned to fly at Croom during the years 1953-54, and went on to become a captain with Western Airlines.

You can see proof that black aviators made history when you visit the College Park Airport Museum, College Park, Maryland. Karen Thiessen is the curator. She is delightfully helpful and knows the subject very well.

Just inside the door, as you turn right, there they are, the hopes and dreams of folks who would be aviators, even if they had to build their own airfield. If you are sentimental, it will look like the logbooks and photographs have been lovingly gathered and placed tenderly by respectful hands into a coffin covered with glass.

On February 11, 1996, at 1:00 P.M., the College Park Airport Museum presented a program on the Columbia Air Center and African-American Aviator John W. Greene, Jr. The museum is located at 1909 Corporal Frank Scott Drive, College Park, Maryland. Herbert Jones was Master of Ceremonies. He is one of the legendary Tuskegee Airmen and is still very active in aviation.

Mr. Jones, age 72, has the bearing and dignity of an old-time aviator, the kind who inspired many young people to become pilots. His stories about Columbia Air Center were told with a tone of modest amusement in his voice and a twinkle in his eye.

"Let me begin by telling you a little about myself," Mr. Jones said. "I am president of Metropolitan Aviation. We operate a flight school at Potomac Airport, a little ways southwest of Andrews AFB. After the war I worked for John Greene, giving flying lessons at Columbia Air Center. When John retired, I managed Columbia Air Center."

Herbert Jones has been a corporate pilot, flying for a man

at Ocean City who had a string of fishing boats up and down the

coast between Ocean City and Savannah, Georgia.

Mr. Jones said, "Many people don't know this. Before Cloud Club was formed, N.D. Butler and Alfred Anderson bought a couple of Piper Cubs and put pontoons on them. That was 1934-1935. They flew them at Buzzard point. It is at the end of First Street SW in Washington, D.C., right across from the old Navy station. John Pinkett got his pilot license there. Learned to fly in the seaplanes."

John Pinkett went to Tuskegee and was an instructor in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Primary flight training at Tuskegee was done by the Civilian Pilot Training program, known as the CPT. Pinkett was soon commissioned a Second Lieutenant and instructed advanced flying.

Mr. Jones continued, "Let me explain something about the CPT. Three Black universities had that program, Howard University, Hampton Institute which is now Hampton University, and West Virginia State. Howard University did their flight training at Columbia Air Center at Croom."

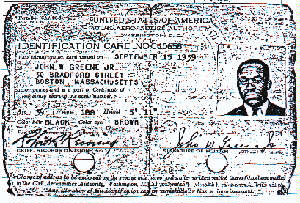

John W. Greene, Jr., was featured in a 1938 story in Flash magazine titled "Colored America on the Wing." They wrote, "True to all aviators, pilot Greene has his pet peculiarities. He always flies bareheaded and wears his parachute."

Mr. Jones talked about John Greene. "He realized very early that Black folks had to learn to work on their own airplanes.

Greene had received pilot certificate number 10658, September 15, 1939, at Boston, Massachusetts and was the only African-American to hold both a pilot license and an aircraft mechanic license. And he is the first African-American awarded the Transport Pilot rating. That last rating is called an Airline Transport Pilot license today, held by pilots flying for the commercial airlines."

Herbert Jones introduced two other speakers, Albert Young and Mel Cooper, who remembered some stories from Columbia Air Center.

Albert Young spoke first. "I learned to fly at Columbia Air Center. The day I first flew solo the wind was twenty-five knots, gusting to about thirty-five." John Greene was Young's instructor.

Greene said, "Well, I think I aim to let you go today."

Young laughed as he remembered, "I thought he meant I could go home. Instead, he was letting me make my first solo flight. That day. Right then and there."

Greene told him, "Yeah, I think you can handle it."

Albert Young never forgot that flight. "When he got out, the airplane was a lot lighter. It leaped into the air. There I was. Now I had to get it back on the ground and made a few passes at the runway. The wind was blowing too hard and pushing me sideways."

Young demonstrated with his hands and continued, "So, I tried another runway. It was the short runway. You came in right across the trees. I think I made about eight or ten passes at that one. Then I decided I would get that airplane on the ground, one way or the other. And I finally got it on the ground."

"Made the best landing in my life." Young smiled and shook his head.

The next speaker was Mel Cooper. He is an official at FAA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Cooper nodded to Herbert Jones and began his story. "I learned to fly at Croom, then worked for the Bureau of Engraving. But I wanted something else. Wanted it very bad. I wanted to be an airplane mechanic. So, I quit my government job. Everybody told me I shouldn't take such a big risk as that."

The next thing his friends knew, Mr. Cooper had finished mechanic school and was working for United Airlines. After that he ended up in Vietnam, working as a civilian mechanic for Air America. Then he went to the FAA to be an aviation safety inspector.

Herbert Jones told a little more about Columbia Air Center. There were a lot of snakes down there and along the river. One day Mr. Jones was flying a Gull Wing Stinson airplane. There was an opening right where the wing strut fastened to the wing. After he landed, a great big snake came out the bottom of the wing and down the strut. It had been up there in the wing while he was flying.

Something else Herbert Jones is very proud of it. You could hear it in his voice when he said, "Columbia Air Center never had a fatality during all the years it operated. That is attributed to John Greene. He made sure everybody followed the rules and all the student pilots were properly trained before they went solo."

The U.S. Navy took over the field and used it for training during World War II. After the war, Columbia Air Center operated until 1956 when the Fisher family refused to renew the lease.

The property was not allowed to disappear into obscurity. It became part of the Patuxent River Watershed Park as the first purchase of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. If you drive down there, all you will find are a few rusting mementos during the walking tour arranged by the Parks Department.

RETURN TO MAIN PAGE

RETURN TO MAIN PAGE