Levitating Architecture - Mies in America (2001)

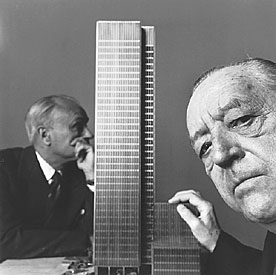

Image - Mies in America in Berlin

The 1950s were very, very kind to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969). In this decade he saw the culmination of a life's work in the form of the Seagram Building (New York City), 860-880 Lake Shore Drive Apartment Buildings (Chicago), Farnsworth House (Plano, Illinois), Toronto-Dominion Centre (Toronto), and the Federal Center (Chicago). The Neue Nationalgalerie (Berlin) followed immediately upon these colossal achievements in the early 1960s.

These buildings have secured his reputation for all time and serve as emphatic statements of his radical architectural project -- a quest for a language of metaphysical precision and tectonic exactitude. This cleansing of architectural syntax was the 'great renewal' Mies intuited in his earliest American projects in the late 1930s.

The closing off of syntax to the vagaries of contingency and the supreme articulation of the desire to soar out of this world was the exact point of Mies' utopian architecture.That this reductionism has also been called a quintessentially American 'pragmatic' thing is quite another matter. Both Manfredo Tafuri and Colin Rowe criticized Mies for undertaking this Icarean task, suggesting that in the process we have collectively been scorched by the sun.

Mies' utopianism came to expression in the skyscrapers and the domestic idyls he perceived as strenuous spiritual exercises, projects that wilfully sought to preclude ever returning to the originary ground of architecture and its phenomenological in-betweenness -- an ontological gap most earnestly papered over in the celebrated "architecture of movement" rhetoric visited upon his work by Miesian apologists. This espoused aesthetic 'movement', the so-called architectural promenade activated by the movement of the spectator through the complex, is pictured at the Whitney in the multi-media accessories to the more staid, candid and static presentation of his work through drawings and models. An entire room is reserved for the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and features a looped, time-lapse video of a day in the life of the art gallery. The score is an eery Philip Glass like piece that has an end of the world, apocalyptic quality. The room also contains a dimly lit model of the project and spotlit photographs by celebrity photographers. This is meant to conclude the exhibition and secures the sacred aura of the re-presentation of Mies' otherworldly weltanschauung.

Photographic and filmic evidence, however, blurs the more forceful distinctions of Mies' art that premiate the free flowing spatial dreamwork at play in his buildings, a play that itself plays with the stunted remains of walls and partitions, translucency and opaqueness. Staged, as they almost always are, on a classical podium and in but not of the city or landscape, the buildings presented in new media format focus the attention instead on the closely cropped architectural emblem or frame -- a set of place markers (joints) or intersecting planes, a meeting of steel and glass, or the selective view to an outside, the other of architecture, the city or the landscape (nature). These choreographed stills and sequences are somatic in that they privilege the body of the building while flirting with its other, the outside. This interpretive game has been present in Mies scholarship since the first waves of adulation accompanying the appearance (and disappearance/reappearance) of the Barcelona Pavilion (1929). The latest articulation of this flirtation is part and parcel of the ongoing rehabilitation of Mies after years of critical neglect; a rehabilitation that began in the early 1990s.

The fact that most of these buildings are optically 'levitated', floating serial simulations of modern dissociation -- soaring, sighing, and secreting themselves in an envelope of glass and attenuated (rolled or extruded) steel or bronze -- is self-evident and the signature trace of the classicism (and scholasticism) at the heart of the main event, the emergence of modern corporate hegemony in the 1950s. Mies' acclaimed architecture is also the climax of the American industrial complex, the conversion of material, physical products to abstract capital, reified, fully mobile and omniscient within its rarefied, secure, sacerdotal precinct -- the office tower or the corporate campus (or the corporatized college campus).

Mies' new home base at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), he was professor of architecture from 1938-58, was the architectural think tank and launching platform for the post-WW2 international style juggernaut. The Armour Institute of Technology (AIT), the precursor to the IIT, and the IIT campus plans of 1939-40 and 1941 respectively, were the sites of emergence for Mies' transformation of modern industrial structure to its highest modality, the 'clear span' or open, homogeneous and infinitely replicable uniform floor plan. Along the way the relationship of skin and skeleton was stretched to it most salient opposition, the building interior disappearing behind, veiled or vaporized by the universal, atomic principles of the envelope and lid (the curtain wall and truss work). Sketches of the Federal Center show that in early facade studies Mies and Company still toyed with differential or expressive variance in the curtain wall (this in 1959) reverting, however, to the universal formula of sameness that he perfected and became the champion of.

Mies fell in love with this tension between inside and outside and made it a virtual fetish, albeit a fetish submerged below the rational, tectonic nature of the structural system. This tortional aesthetic fueled his subtle polemic of modern architecture's transcendent otherness, a philosophical pose nourished by his readings of seminal theoretical and historical texts of the modern era; for example, Rudolf Schwarz's (The Church Incarnate: The Sacred Function of Christian Architecture, 1958), Jacques Maritain's (Art and Scholasticism, 1943) and Martin Heidegger's (Kant und das problem der metaphysik, 1929). These texts are presented by the Whitney as typical of the "thirty" books Mies valued above all others out of nearly 3000 he claimed to have read. The thematic subtext is the re-enunciation of the spiritual in the modern and the triumph of the transcendent over the immanent.

Given this lifelong architectural gambit by Mies, the recent attempt by architectural historians to restore immanence to Mies projects seems highly suspect. Such critical operations claim the accidental and ambient tones of city and environment as an inherent surplus of the architect's sensibility. These accidental fluctuations both permeate and engulf the architectural object and provide a sublime incidental figure of heterogeneity. They are more likely a return of repressed content -- an at-odds and underwhelming claim by Miesians given the legend and myth of perfectionism perpetrated by such pundits left, right and center for years on end. They are more likely a psycho-dynamic function of the critical community itself as it tries to escape the clammy enclosure of the hermeneutic circle. The magical aura, the play of light and shadow, the movement of the spectator among the shifting, gridded, horizontal vectors of Mies' work is certainly part of the secret Mies; but this primal subliminal secret is presented as a surreptitious supplement to the gauzy and adoring gaze of the Miesian set (notwithstanding the more honest and brutal recent retroactive reappraisal of modern architecture and its presumptions by nonpartisans).

When all is said and done, the 'outlander' or the post-humanist subject of the disenchanted spaces of modern cities and modern space is the ideal, first-person singular observer of Mies -- the self-same blurry alien interloper of Mies sketches, a figure of the transfixed 'I', the lapsed notional self fixed in the headlights of the oncoming and onrushing dematerialization of life. This crystalized state, a precursor to a shattered state, is the last threshold before the atomization and complete subjection of architecture's ancient dyadic/dialectic ground -- self and everything else. Immersed in the spaces of immensity and universality, engulfed in the interior micro-climates and exacting dimensional elan of modular architecture, subsumed by the space-time continuum, lost in other words in indifference and coincidence, is contingency, the random, the chaotic, the regenerative and the whole vast remainder of the thing, the vestige and the real. The ubiquity of the universal is the loosing of a firestorm, the unleashing of the archetype in the world, and the destruction of the generative matrix forever held in check outside of the charmed boxes of modernity.

Fortunately the Miesian moment has long passed and this most recent resurfacing is nothing more than an attempt to salvage his legacy and to suggest 'sightings' of a very different Mies in the rearview mirror of revisionism. To call this revisionism mean-spirited would be misleading. To understand that it is intended to act as a corrective to the long-standing misrepresentation of Mies would be to grant it far too much significance. Far better to laugh and move on to the next big thing on the curatorial horizon whatever that may turn out to be. (Gavin Keeney - 1383 words)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mies in America (The Whitney)

Mies in Berlin< (MoMA)

Mies in America (New York: Abrams, 2001)

POSTSCRIPT

This review owes a debt of gratitude to the following two books: Fear of Glass (Barcelona/Basel: Actar/Birkhauser, 2001), by Josep Quetglas, and Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space, by Elizabeth Grosz (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press/ANY Corporation, 2001).

See Regarding Mies for a review of Fear of Glass and Looking for Mies, both from Birkhauser.

KUDOS

Iņigo Manglano-Ovalle, the designer of the Whitney Mies exhibition, received a 2001 MacArthur "genius" award.