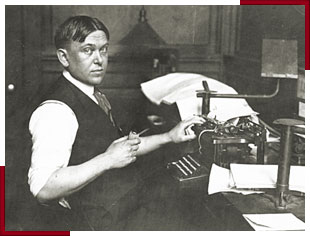

H. L Mencken on Religion

H. L Mencken on Religion

Henry

Louis Mencken (1880-1956) U. S. Editor and Critic.

Freelance

Days

The Cosmic Secretariat

From

HIGH AND GHOSTLY MATTERS, PREJUDICES: FOURTH SERIES,

1924,

pp. 61-65.

First printed in the American

Mercury, Jan., 1924, pp. 75-76

The argument from design, once the bulwark of Christian

apologetics, has been shot so full of holes that it is no wonder it has had to

be abandoned. The more, indeed, the theologian seeks to prove the wisdom and

omnipotence of God by His works, the more he is dashed by the evidences of

divine incompetence and stupidity that the advance of science is constantly

turning up. The world is not actually well run; it is very badly run, and no

Huxley was needed to labor the obvious fact. The human body, very cunningly

designed in some details, is cruelly and senselessly bungled in other details,

and every reflective first-year medical student must notice a hundred ways to

improve it. How are we to reconcile this mixture of finesse and blundering with

the concept of a single omnipotent Designer, to whom all problems are equally

easy? If He could contrive so efficient and durable a machine as the human hand,

then how did He come to make such botches as the tonsils, the gallbladder, the

ovaries and the prostate gland? If He could perfect the elbow and the ear, then

why did He boggle the teeth?

Having never encountered a satisfactory - or even a

remotely plausible - answer to such questions, I have had to go to the trouble

of devising one myself. It is, at all events, quite simple, and in strict accord

with all the known facts. In brief, it is this: that the theory that the

universe is run by a single God must be abandoned, and that in place of it we

must set up the theory that it is actually run by a board of gods, all of equal

puissance and authority. Once this concept is grasped the difficulties that have

vexed theologians vanish, and human experience instantly lights up the whole

dark scene. We observe in everyday life what happens when authority is divided,

and great decisions are reached by consultation and compromise. We know that the

effects at times, particularly when one of the consultants runs away with the

others, are very good, but we also know that they are usually extremely bad.

Such a mixture, precisely, is on display in the cosmos. It presents a series of

brilliant successes in the midst of an infinity of failures.

I contend that my theory is the only one ever put forward

that completely accounts for the clinical picture. Every other theory, facing

such facts as sin, disease and disaster, is forced to admit the supposition that

Omnipotence, after all, may not be omnipotent - a plain absurdity. I need toy

with no such blasphemous nonsense. I may assume that every god belonging to the

council which rules the universe is infinitely wise and infinitely powerful,

and yet not evade the plain fact that most of the acts of that council are

ignorant and foolish. In truth, my assumption that a council exists is

tantamount to an a priori assumption

that its acts are ignorant and foolish, for no act of any conceivable council

can be otherwise. Is the human hand perfect, or, at all events, practical and

praiseworthy? Then I account for it on the ground that it was designed by some

single member of the council - that the business was turned over to him by

inadvertence or as a result of an irreconcilable difference of opinion among the

others.. Had more than one member participated actively in its design it would

have been measurably less meritorious than it is, for the sketch offered by the

original designer would have been forced to run the gauntlet of criticisms and

suggestions from all the other councilors, and human experience teaches us that

most of these criticisms and suggestions would have been inferior to the

original idea - that many of them, in fact, would have had nothing in them save

a petty desire to maul and spoil the original idea.

But do I here accuse the high gods of harboring

discreditable human weaknesses? If I do, then my excuse is that it is impossible

to imagine them doing the work universally ascribed to them without admitting

their possession of such weaknesses. One cannot imagine a god spending weeks and

months, and maybe whole geological epochs, laboring over the design of the human

kidney without assuming him to have been moved by a powerful impulse to express

himself vividly, to marshal and publish his ideas, to win public credit among

his fellows - in brief, without assuming him to be egoistic. And one cannot

assume him to be egoistic without assuming him to prefer the adoption of his own

ideas to the adoption of any other god’s. I defy anyone to make the contrary

assumption without plunging instantly into clouds of mysticism. Ruling it out,

one comes inevitably to the conclusion that the inept management of the universe

must be ascribed to clashes of egos, i.e., to spites and revenges, among the

gods, for any one of them alone, since we must assume him to be infinitely wise

and powerful, could run it perfectly. We suffer from bad stomachs simply because

the god who first proposed making a stomach aroused thereby the ill-nature of

those who had not thought of it, and because they proceeded instantly to wreak

that ill-nature upon him by improving, i.e., botching, his work. We must

reproduce our species in the familiar arduous, uneconomic, indecent and almost

pathological manner because the god who devised the excellent process prevailing

among the protozoa had to be put in his place when he proposed to extend it to

the Primates.

The Nature of Faith

From the same, pp. 65-76

Many years ago, when I was more reckless intellectually

than I am today, I proposed the application of Haeckel’s biogenetic law - to

wit, that the history of the individual rehearses the history of the species to

the domain of ideas. So applied, it leads to some superficially startling but

probably quite sound conclusions, for example, that an adult poet is simply an

individual in a state of arrested development - in brief, a sort of moron. Just

as all of us, in utero, pass through a

stage in which we are tadpoles, and almost indistinguishable from the tadpoles

which afterward become frogs, so all of us pass through a stage, in our nonage,

when we are poets. A youth of seventeen who is not a poet is simply a donkey:

his development has been arrested even anterior to that of the tadpole. But a

man of fifty who still writes poetry is either an unfortunate who has never

developed, intellectually, beyond his teens, or a conscious buffoon who pretends

to be something that he isn’t - something far younger and juicier than he

actually is.

At adolescence large numbers of individuals, and maybe

even most, have similar attacks of piety, but that is only saying that their

powers of perception, at that age, outrun their knowledge. They observe the

tangled and terrifying phenomena of life, but cannot account for them. Later on,

unless their development is arrested, they gradually emerge from that romantic

and spookish fog, just as they emerge from the hallucinations of poetry. I speak

here, of course, of individuals genuinely capable of education - always a small

minority. If, as the Army tests of conscripts showed, nearly 50 per cent of

American adult males never get beyond the mental development of a

twelve-year-old child, then it must be obvious that a much smaller number get

beyond the mental development of a youth at the end of his teens. I put that

number, at a venture, at 10 per cent. The remaining 90 per cent never quite free

themselves from religious superstitions. They may no longer believe it is an act

of God every time an individual catches a cold, or sprains his ankle, of cuts

himself shaving, but they are pretty sure to see some trace of divine

intervention in it if he is struck by lightning, or hanged, or afflicted with

leprosy or syphilis.

All modern religions are based, at least on their logical

side, on this notion that there are higher powers which observe the doings of

man and constantly take a hand in them, and in the fold of Christianity, which

is a good deal more sentimental than any other major religion, the concept of

interest and intervention is associated with a concept of benevolence. In other

words, it is believed that God is predominantly good. No true Christian can

tolerate the idea that God ever deliberately and wantonly injures him, or could

conceivably wish him ill. The slings and arrows that he suffers, he believes,

are brought down upon him by his own ignorance and contumacy. Unhappily, this

doctrine of the goodness of God does not fit into what we know of the nature and

operations of the cosmos today; it is a survival from a day of universal

ignorance. All science is simply a great massing of proofs that God, if He

exists, is really neither good nor bad, but simply indifferent - an infinite

Force carrying on the operation of unintelligible processes without the

slightest regard, either one way or the other, for the comfort, safety and

happiness of man.

Why, then, does this belief survive? Largely, I am

convinced, because it is supported by that other hoary relic from the

adolescence of the race, to wit, the weakness for poetry. The Jews fastened

their religion upon the Western world, not because it was more reasonable than

the religions of their contemporaries - as a matter of fact, it was vastly less

reasonable than many of them - but because it was far more poetical. The poetry

in it was what fetched the decaying Romans, and after them the barbarians of the

North; not the so-called Christian evidences. No better has ever been written.

It is so powerful in its effects that even men who reject its content in

toto are more or less susceptible. One hesitates to flout it on purely

esthetic grounds; however dubious it may be in doctrine, it is nevertheless

almost perfect in form, and so even the most violent atheist tends to respect

it, just as he respects a beautiful but deadly toadstool. For no man, of course,

ever quite gets over poetry. He may seem to have recovered from it, just as he

may seem to have recovered from the measles of his school-days, but exact

observation teaches us that no such recovery is ever quite perfect; there

al-ways remains a scar, a weakness and a memory.

Now, there is reason for maintaining that the taste for

poetry, in the process of human development, marks a stage measurably later than

the stage of religion. Savages so little cultured that they know no more of

poetry than a cow have elaborate and often very ingenious theologies. If this be

true, then it follows that the individual, as he rehearses the life of the

species, is apt to carry his taste for poetry further along than he carries his

religion - that if his development is arrested at any stage before complete

intellectual maturity that arrest is far more likely to leave hallucinations.

Thus, taking men in the mass, there are many more natural victims of the former

than of the latter - and here is where the artfulness of the ancient Jews does

its execution. It holds countless thousands to the faith who are actually

against the faith, and the weakness with which it holds them is their weakness

for poetry, i.e., for the beautiful but untrue. Put into plain, harsh words most

of the articles they are asked to believe would revolt them, but put into

sonorous dithyrambs the same articles fascinate and overwhelm them.

This persistence of the weakness for poetry explains the

curious growth of ritualism in an age of skepticism. Almost every day theology

gets another blow from science. So badly has it been battered during the past

century, indeed, that educated men now give it little more credence than they

give to sorcery, its ancient ally. But squeezing out the logical nonsense does

no damage to the poetry; on the contrary, it frees, and, in a sense, dignifies

the poetry. Thus there is a constant movement of Christians, and particularly of

newly-intellectual Christians, from the more literal varieties of Christian

faith to the more poetical varieties. The normal idiot, in the United States, is

born a Methodist or a Baptist, but when he begins to lay by money he and his

wife tend to go over to the American out-house of the Church of England, which

is not only more fashionable but also less revolting to the higher cerebral

centers. His daughter, when she emerges from the finishing school, is very High

Church; his granddaughter, if the family keeps its securities, may go the whole

hog by embracing Rome.

In view of all this, I am convinced that the Christian

church, as a going concern, is quite safe from danger in the United States,

despite the rapid growth of agnosticism. The theology it merchants is full of

childish and disgusting absurdities; practically all the other religions of

civilized and semi-civilized man are more plausible. But all of these religions,

including Islam, contain the fatal defect that they appeal primarily to the

reason. Christianity will survive not only Modernism but also Fundamentalism, a

much more difficult business. It will survive because it makes its first and

foremost appeal to that moony sense of the poetic which lingers in all men - to

that elemental sentimentality which, in men of arrested mental development,

which is to say, in the average men of Christendom, passes for the passion to

seek and know beauty.,,

1 The reader fetched by this argument will

find more to his taste in my Treatise on the Gods, second edition, 1946, pp.

286-89.

The Restoration of Beauty

From the same, pp. 77-78

The Christians of the Apostolic Age were almost exactly

like the modern Holy Rollers - men quite without taste or imagination, whoopers

and shouters, low vulgarians, cads. So far as is known, their public worship was

wholly devoid of the sense of beauty; their sole concern was with the salvation

of their so-called souls. Thus they left us nothing worth preserving - not a

single church, or liturgy, or even hymn. The objects of art exhumed from the

Catacombs are inferior to the drawings and statuettes of Cro-Magnon man. All the

moving beauty that adorns the corpse of Christianity today came into being long

after the Fathers had perished. The faith was many centuries old before

Christians began to build cathedrals. We think of Christmas as the typical

Christian festival, and no doubt it is; none other is so generally kept by

Christian sects, or so rich in charm and beauty. Well, Christmas, as we now have

it, was almost unknown in Christendom until the Eleventh Century, when the

relics of St. Nicholas of Myra, originally the patron of pawnbrokers, were

brought from the East to Italy. All this time the Universal Church was already

torn by controversies and menaced by schisms, and the shadow of the Reformation

was plainly discernible in the West. Religions, in fact, like castles, sunsets

and women, never reach their maximum of beauty until they are touched by

decay.

Holy Clerks

From the same, pp. 79-84. First printed in the American

Mercury, June, 1924, p. 183

Around no class of men do more false assumptions cluster

than around the rev. clergy, our lawful commissioners at the Throne of Grace. I

proceed at once to a crass example: the assumption that clergymen are

necessarily religious. Obviously, it is widely cherished, even by clergymen

themselves. The most ribald of us, in the presence of a holy clerk, is a bit

self-conscious. I am myself given to criticizing Divine Providence somewhat

freely, but in the company of the rector of my parish, even at the Biertisch,

I tone down my animadversions to a level of feeble and polite remonstrance. I

know the fellow too well, of course, to have any actual belief in his piety. He

is, in fact, rather less pious than the average right-thinking Americano, and I

doubt gravely that the sorceries he engages in professionally every day awaken

in him any emotion more lofty than boredom. I have heard him pray for the

President and Congress, the heathen and for rain, but I have never heard him

pray for himself. Nevertheless, the public assumption that he is highly devout,

though I dispute it, colors all my intercourse with him, and deprives him of

hearing some of my most searching and intelligent observations.

All that is needed to expose the hollowness of this

ancient delusion is to consider the chain of causes which brings a young man to

taking holy orders. Is it, in point of fact, an irresistible religious impulse

that sets him to studying exegetics, homiletics and the dog-Greek of the New

Testament, and an irresistible religious impulse only, or is it something quite

different? I believe that it is something quite different, and that that

some-thing may be described briefly as a desire to shine in the world without

too much effort. The young theologue, in brief, is commonly an ambitious but

somewhat lazy fellow, and he studies theology instead of osteopathy,

salesmanship or the law because it offers a quicker and easier route to an

assured job and public respect. The sacred sciences may be nonsensical, but they

at least have the vast virtue of short-circuiting, so to speak, the climb up the

ladder of security. The young medical man, for a number of years after he is

graduated, either has to work for nothing or to content himself with the dregs

of practise, and the young lawyer, unless he has unusual influence or complete

atrophy of the conscience, often teeters on the edge of actual starvation. But

the young divine is a safe and distinguished man the moment he is ordained;

indeed, his popularity, especially among the faithful who are fair, is often

greater at that moment than it ever is afterward. His livelihood is assured

instantly. At one stroke, he becomes a person of dignity and importance, eminent

in his community, deferred to even by those who question his magic, and vaguely

and pleasantly feared by those who credit it.

These facts, you may be sure, are not concealed from

aspiring young men of the sort I have mentioned. Such young men have eyes, and

even a certain capacity for ratiocination. They observe the nine sons of the

police sergeant: one a priest at twenty-five, with a fine house to live in,

invitations to all the birthday parties for miles around, and plenty of time to

go to the ball-game on Summer afternoons; the others struggling desperately to

make their livings as furniture-movers, tin-roofers and bus-drivers. They

observe the young Protestant dominie in his Ford sedan, flitting about among the

women while their husbands labor down in the yards district, a clean collar

around his neck, a solid meal of fried chicken in his gizzard, and his name in

the local paper every day. Only crazy women ever fall in love with young

insurance solicitors, but every young clergyman, if he is so inclined, may have

a whole seraglio. Even if he is celibate, the gals bathe him in their smiles; in

truth, the more celibate he is, the more attention he gets from them. No wonder

his high privileges and immunities propagate the sin of envy. No wonder there

are still candidates for the holy shroud, despite the vast growth of atheism

among us.

The daily duties of a professional man of God

have nothing to do with religion, but are basically social or commercial. In so

far as he works at all, he works as the general manager of a corporation, and

only too often it is in financial difficulties and rent by factions among the

stockholders. His specifically theological hocus-pocus is of a routine and

monotonous nature, and must needs depress him mightily, as a surgeon is

depressed by the endless opening of boils. He gets rid of spiritual exaltation

by reducing it to a hollow formality, as a politician gets rid of patriotism and

a lady of joy of love. He becomes, in the end, quite anesthetic to religion, and

even hostile to it. The fact is made distressingly visible by the right rev. the

bench of bishops. For a bishop to fall on his knees spontaneously and, begin to

pray to God would make almost as great a scandal as if he mounted his throne in

a bathing suit. The piety of the ecclesiastic, on such high levels, becomes

wholly theoretical. The servant of God has been lifted so near to the saints and

become so familiar with the inner workings of the divine machinery that all awe

and wonder have oozed out of him. He can no more undergo a genuine religious

experience than a veteran scene shifter can laugh at the wheezes of the First

Gravedigger. It is, perhaps, well that this is so. If the higher clergy were

actually religious some of their own sermons and pastoral epistles would scare

them to death.

The Collapse of Protestantism

From PROTESTANTISM IN THE REPUBLIC, PREJUDICES: FIFTH

SERIES, 1926, PP. 104-19

First

printed in the American Mercury, March,

1925, pp. 286-88

That Protestantism in this great Christian realm is down

with a wasting disease must be obvious to every amateur of ghostly pathology.

One half of it is moving, with slowly accelerating speed, in the direction of

the Harlot of the Seven Hills: the other is sliding down into voodooism. The

former carries the greater part of Protestant money with it; the latter carries

the greater part of Protestant libido. What remains in the middle may be likened

to a torso without either brains to think with or legs to dance - in other

words, something that begins to be professionally attractive to the mortician,

though it still makes shift to breathe. There is no lack of life on the higher

levels, where the more solvent Methodists and the like are gradually

transmogrified into Episcopalians, and the Episcopalians shin up the ancient

bastions of Holy Church, and there is no lack of life on the lower levels, where

the rural Baptists, by the route of Fundamentalism, rapidly descend to the

dogmas and practises of the Congo jungle. But in the middle there is desiccation

and decay. Here is where Protestantism was once strongest. Here is the region of

the plain and godly Americano, fond of devotion but distrustful of every hint of

orgy - the honest fellow who suffers dutifully on Sunday, pays his tithes, and

hopes for a few kind words from the pastor when his time comes to die. Today,

alas, he tends to absent himself from pious exercises, and the news goes about

that there is something the matter with the churches, and the denominational

papers bristle with schemes to set it right, and many up-and-coming pastors,

tiring of preaching and parish work, get jobs as the executive secretaries of

these schemes, and go about the country expounding them to the faithful.

The extent to which Protestantism, in its upper reaches,

has succumbed to the lascivious advances of Rome seems to be but little

apprehended by the majority of connoisseurs. I was myself unaware of the whole

truth until a recent Christmas, when, in the pursuit of a quite unrelated

inquiry, I employed agents to attend all the services held in the principal

Protestant basilicas of an eminent American city, and to bring in the best

reports they could formulate upon what went on in the lesser churches. The

substance of these reports, in so far as they related to churches patronized by

the well-to-do, was simple: they revealed a head-long movement to the right, an

almost precipitate flight over the mountain. Six so-called Episcopal churches

held midnight services on Christmas Eve in obvious imitation of Catholic

midnight masses, and one of them actually called its service a solemn high mass.

Two invited the nobility and gentry to processions, and a third concealed a

procession under the name of a pageant. One offered Gounod’s St. Cecilia mass

on Christmas morning, and another the Messe Solennelle by the same composer;

three others, somewhat more timorous, contented themselves with parts of masses.

One, throwing off all pretense and euphemism, summoned the faithful to no less

than three Christmas masses, naming them by name - two low and one high. All six

churches were aglow with candles, and two employed incense.

But that was not the worst. Two Presbyterian churches and

one Baptist church, not to mention five Lutheran churches of different synods,

had carol services in the dawn of Christmas morning, and the one attended by the

only one of my agents who got up early enough - it was in a Presbyterian church

- was made gay with candles, and had a pallpably Roman smack. Yet worse: a rich

and conspicuous Methodist church, patronized by the leading Wesleyan wholesalers

and moneylenders of the town, boldly offered a “medieval” carol service.

Medieval? What did that mean? The Middle Ages ended on July 16, 1453, at 12

o’clock meridian, and the Reformation was not launched by Martin Luther until

October 31, 1517, at 10.15 a.m. If medieval, in the sense in which it was here

used, did not mean Roman Catholic, then I surely went to school in vain. My

agent, born a Methodist, reported that the whole ceremony shocked him

excessively. It began with trumpet blasts from the church spire and it concluded

with an Ave Maria by a vested choir. Candles rose up in glittering ranks behind

the chancel rail, and above them glowed a shining electric star. God help us

all, indeed! What next? Will the rev. pastor, on some near tomorrow, defy the

lightning bolts of Yahweh by appearing in alb and dalmatic? Will he turn his

back upon the faithful? Will he put in a telephone booth for auricular

confession?

Certainly no one argues that the use of candles in public

worship would have had the sanction of the Ur-Wesleyans, or that they would have

consented to Blasmusik and a vested

choir. Down to sixty or seventy years ago, in fact, the Methodists prohibited

Christmas services altogether, as Romish and heathen. But now we have ceremonies

almost operatic. As I have said, the Episcopalians - who, in most American

cities, are largely ex-Methodists or ex-Presbyterians, or, in New York, ex-Jews

- go still further. In three of the

churches attended by my agents Holy Communion was almost indistinguishable from

a mass - and in every one there was a good house and what the colored pastors

call a good plate. Even the Methodists who remain Methodists begin to wobble.

Tiring of the dreadful din that goes with the orthodox Wesleyan demonology, they

take to goings-on that grow more and more stately and voluptuous. The sermon

ceases to be a cavalry charge, and becomes soft and pizzicato.

The choir abandons “Throw Out the Life-Line” and “Are You Ready for

the Judgment Day?” and toys with Handel. It is an evolution that has, viewed

from a tree, a certain merit. The stock of nonsense in the world is sensibly

diminished and the stock of beauty augmented. But what would the old time

circuit riders say of it, imagining them miraculously brought back from Hell?

So much for the volatilization that is going on above the

diaphragm. What is in progress below? All I can detect is a rapid descent to

mere barbaric devil chasing. In all those parts of the Republic where Beelzebub

is still real - for example, in the rural sections of the Middle West and

everywhere in the South save a few walled towns -the evangelical sects plunge

into an abyss of malignant imbecility, and declare a holy war upon every decency

that civilized men cherish. They have thrown the New Testament overboard, and

gone back to the Old, and particularly to the bloodiest parts of it. What one

mainly notices about the clerics who lead them is their vast lack of sound

information and sound sense. They constitute, perhaps, the most ignorant class

of teachers ever set up to guide a presumably civilized people; they are even

more ignorant than the county superintendents of schools. Learning, indeed, is

not esteemed in the evangelical denominations, and any literate plow-hand, if

the Holy Spirit inflames him, is thought to be fit to preach. Is he commonly

sent, as a preliminary, to a training camp, to college? But what a college! You

will find one in every mountain valley of the land, with its single building in

its bare pasture lot, and its faculty of half-idiot pedagogues and broken-down

preachers. One man, in such a college, teaches oratory, ancient history,

arithmetic and Old Testament exegesis. The aspirant comes in from the barnyard,

and goes back in a year or two to the village. His body of knowledge is that of

a bus driver or a vaudeville actor. But he has learned the clichés of his

craft, and he has got him a black Sunday coat, and so he has made his escape

from the harsh labors of his ancestors, and is set up as a fountain of light and

learning.

Immune

From the American Mercury, March, 1930, p. 289.

First printed, in part, in

the Baltimore Evening Sun, Dec. 9, 1929

The most curious social convention of the great age in

which we live is the one to the effect that religious opinions should be

respected. Its evil effects must be plain enough to everyone. All it

accomplishes is (a) to throw a veil of

sanctity about ideas that violate every intellectual decency, and (b) to make

every theologian a sort of chartered libertine. No doubt it is mainly to blame

for the appalling slowness with which really sound notions make their way in the

world. The minute a new one is launched, in whatever fields, some imbecile of a

theologian is certain to fall upon it, seeking to put it down. The most

effective way to defend it, of course, would be to fall upon the theologian, for

the only really workable defense, in polemics as in war, is a vigorous

offensive. But convention frowns upon that device as indecent, and so

theologians continue their assault upon sense without much resistance, and the

enlightenment is unpleasantly delayed.

There is, in fact, nothing about religious opinions that

entitles them to any more respect than other opinions get. On the contrary, they

tend to be noticeably silly. If you doubt it, then ask any pious fellow of your

acquaintance to put what he believes into the form of an affidavit, and see how

it reads... . “I, John Doe, being duly sworn, do say that I believe that, at

death, I shall turn into a vertebrate without substance, having neither weight,

extent nor mass, but with all the intellectual powers and bodily sensations of

an ordinary mammal; . . . and that, for the high crime and misdemeanor of having

kissed my sister-in-law behind the door, with evil intent, I shall be boiled in

molten sulphur for one billion calendar years.” Or, “I, Mary Roe, having the

fear of Hell before me, do solemnly affirm and declare that I believe it was

right, just, lawful and decent for the Lord God Jehovah, seeing certain little

children of Beth-el laugh at Elisha’s bald head, to send a she-bear from the

wood, and to instruct, incite, induce and command it to tear forty-two of them

to pieces.” Or, “I, the Right Rev._____ _________, Bishop of _________,D.D.,

LL.D., do honestly, faithfully and on my honor as a man and a priest, declare

that I believe that Jonah swallowed the whale,” or vice

versa, as the case may be. No, there is nothing notably dignified about

religious ideas. They run, rather, to a peculiarly puerile and tedious kind of

nonsense. At their best, they are borrowed from metaphysicians, which is to say,

from men who devote their lives to proving that twice two is not always or

necessarily four. At their worst, they smell of spiritualism and fortune

telling. Nor is there any visible virtue in the men who merchant them

professionally. Few theologians know anything that is worth knowing, even about

theology, and not many of them are honest. One may forgive a Communist or a

Single Taxer on the ground that there is something the matter with his ductless

glands, and that a Winter in the south of France would relieve him. But the

average theologian is a hearty, red-faced, well-fed fellow with no discernible

excuse in pathology. He disseminates his blather, not innocently, like a

philosopher, but maliciously, like a politician. In a well-organized world he

would be on the stone-pile. But in the world as it exists we are asked to listen

to him, not only politely, but even reverently, and with our mouths open.

A New Use for Churches

From

DAMN! A BOOK OF CALUMNY, 1918, pp. 88-89

Granting the existence of God, a house dedicated to Him

naturally follows. He is all-important; it is fit that man should take some

notice of Him. But why praise and flatter Him for His unspeakable cruelties? Why

forget so supinely His failures to remedy the easily remediable? Why, indeed,

devote the churches exclusively to worship? Why not give them over, now and

then, to justifiable indignation meetings?

If God can hear a petition, there is no ground for

holding that He would not hear a complaint. It might, indeed, please Him to find

His creatures grown so self-reliant and reflective. More, it might even help Him

to get through His infinitely complex and difficult work. Theology, in fact, has

already moved toward such notions. It has abandoned the primitive doctrine of

God’s arbitrariness and indifference, and substituted the doctrine that He is

willing, and even eager, to hear the desires of His creatures - i.e., their

private notions, born of experience, as to what would be best for them. Why

assume that those notions would be any the less worth hearing and heeding if

they were cast in the form of criticism, and even of denunciation? Why hold that

the God who can understand and forgive even treason could not understand and

forgive remonstrance?

Free Will

From

the same, pp. 91-94

Free

will, it appears, is still an essential dogma to most Christians. Without it the

cruelties of God would strain faith to the breaking point. But outside the fold

it is gradually falling into decay. Men of science have dealt it staggering

blows, and among laymen of inquiring mind it seems to be giving way to an

apologetic sort of determinism - a determinism, one may say, tempered by

defective observation. Mark Twain, in his secret heart, was such a determinist.

In his “What Is Man?” you will find him at his farewells to libertarianism.

The vast majority of our acts, he argues, are determined, but there remains a

residuum of free choices. Here we stand free of compulsion and face a pair or

more of alternatives, and are free to go this way or that.

A pillow for free will to fall upon - but one loaded with

disconcerting brickbats. Where the occupants of this last trench of

libertarianism err is in their assumption that the pulls of their antagonistic

impulses are exactly equal - that the individual is absolutely free to choose

which one he will yield to. Such freedom, in practise, is never encountered.

When an individual confronts alternatives, it is not alone his volition that

chooses between them, but also his environment, his inherited prejudices, his

race, his color, his condition of servitude. I may kiss a girl or I may not kiss

her, but surely it would be absurd to say that I am, in any true sense, a free

agent in the matter. The world has even put my helplessness into a proverb. It

says that my decision and act depend upon the time, the place - and even to some

extent, upon the girl.

Examples might be multiplied ad infinitum. I can scarcely remember performing a wholly voluntary

act. My whole life, as I look back upon it, seems to be a long series of

inexplicable accidents, not only quite unavoidable, but even quite

unintelligible. Its history is the history of the reactions of my personality to

my environment, of my behavior before external stimuli. I have been no more

responsible for that personality than I have been for that environment. To say

that I can change the former by a voluntary effort is as ridiculous as to say

that I can modify the curvature of the lenses of my eyes. I know, because I have

often tried to change it, and always failed. Nevertheless, it has changed. I am

not the same man I was in the last century. But the gratifying improvements so

plainly visible are surely not to be credited to me. All of them came from

without - or from unplumbable and uncontrollable depths within.

The more the matter is examined the more the residuum of

free will shrinks and shrinks, until in the end it is almost impossible to find

it. A great many men, of course, looking at themselves, see it as something very

large; they slap their chests and call themselves free agents, and demand that

God reward them for their virtue. But these fellows are simply egoists devoid of

a critical sense. They mistake the acts of God for their own acts. They are

brothers to the fox who boasted that he had made the hounds run.

The throwing overboard of free will is commonly denounced

on the ground that it subverts morality, and makes of religion a mocking. Such

pious objections, of course, are foreign to logic, but nevertheless it may be

well to give a glance to this one. It is based upon the fallacious hypothesis

that the determinist escapes, or hopes to escape, the consequences of his acts.

Nothing could be more untrue. Consequences follow acts just as relentlessly if

the latter be involuntary as if they be voluntary. If I rob a bank of my free

choice or in response to some unfathomable inner necessity, it is all one; I go

to the same jail. Conscripts in war are killed just as often as volunteers.

Even on the ghostly side, determinism does not do much

damage to theology. It is no harder to believe that a man will be damned for his

involuntary acts than it is to believe that he will be damned for his voluntary

acts, for even the supposition that he is wholly free does not dispose of the

massive fact that God made him as he is, and that God could have made him a

saint if He had so desired. To deny this is to flout omnipotence - a crime at

which I balk. But here I begin to fear that I wade too far into the hot waters

of the sacred sciences, and that I had better retire before I lose my hide. This

prudent retirement is purely deterministic. I do not ascribe it to my own

sagacity; I ascribe it wholly to that singular kindness which fate always shows

me. If I were free I’d probably keep on, and then regret it afterward.

Sabbath Meditation

In part from the American Mercury, May, 1924, pp. 60-61, and in part

from the Smart Set, Oct., 1923, pp. 138-42

My essential trouble, I sometimes suspect, is that I am

quite devoid of what are called spiritual gifts. That is to say, I am incapable

of religious experience, in any true sense. Religious ceremonials often interest

me esthetically, and not infrequently they amuse me otherwise, but I get

absolutely no stimulation out of them, no sense of exaltation, no mystical catharsis.

In that department I am as anesthetic as a church organist, an archbishop or an

altar boy. When I am low in spirits and full of misery, I never feel any impulse

to seek help, or even mere consolation, from supernatural powers. Thus the

generality of religious persons remain mysterious to me, and vaguely offensive,

as I am unquestionably offensive to them. I can no more understand a man praying

than I can understand him carrying a rabbit’s foot to bring him luck. This

lack of understanding is a cause of enmities, and I believe that they are sound

ones. I dislike any man who is pious, and all such men that I know dislike me.

I am anything but a militant atheist and haven’t the

slightest objection to church going, so long as it is honest. I have gone to

church myself more than once, honestly seeking to experience the great inward

kick that religious persons speak of. But not even at St. Peter’s in Rome have

I sensed the least trace of it. The most I ever feel at the most solemn moment

of the most pretentious religious ceremonial is a sensuous delight in the beauty

of it - a delight exactly like that which comes over me when I hear, say,

“Tristan and Isolde” or Brahms’ fourth symphony. The effect of such music,

in fact, is much keener than the effect of the liturgy. Brahms moves me far more

powerfully than the holy saints.

As I say, this deficiency is a handicap in a world

peopled, in the overwhelming main, by men who are inherently religious. It sets

me apart from my fellows and makes it difficult for me to understand many of

their ideas and not a few of their acts. I see them responding constantly and

robustly to impulses that to me are quite inexplicable. Worse, it causes these

folks to misunderstand me, and often to do me serious injustice. They cannot rid

themselves of the notion that, because I am anesthetic to the ideas which move

them most profoundly, I am, in some vague but nevertheless certain way, a man of

aberrant morals, and hence one to be kept at a distance. I have never met a

religious man who did not reveal this suspicion. No matter how earnestly he

tried to grasp my point of view, he always ended by making an alarmed sort of

retreat. All religions, in fact, teach that dissent is a sin; most of them make

it the blackest of all sins, and all of them punish it severely whenever they

have the power. It is impossible for a religious man to rid himself of the

notion that such punishments are just. He simply cannot imagine a civilized rule

of conduct that is not based upon the fear of God.

Let me add that my failing is in the fundamental

religious impulse, not in mere theological credulity. I am not kept out of the

church by an inability to believe the current dogmas. In point of fact, a good

many of them seem to me to be reasonable enough, and I probably dissent from

most of them a good deal less violently than many men who are assiduous

devotees. Among my curious experiences, years ago, was that of convincing an

ardent Catholic who balked at the dogma of papal infallibility. He was a very

faithful son of the church and his inability to accept it greatly distressed

him. I proved to him, at least to his satisfaction, that there was nothing

intrinsically absurd in it - that if the dogmas that he already accepted were

true then this one was probably true also. Some time later, when this man was on

his deathbed, I visited him and he thanked me simply and with apparent sincerity

for resolving his old doubt. But even he was unable to comprehend my own lack of

religion. His last words to me were a pious hope that I would give over my

lamentable contumacy to God and lead a better life. He died firmly convinced

that I was headed for Hell, and, what is more, that I deserved it.

The Immortality of the Soul

From

the American Mercury, Sept., 1932, pp.

125-26

When it comes to the immortality of the soul, whatever

that may be precisely, I can only say that it seems to me to be wholly

incredible and preposterous. There is not only no plausible evidence for it:

there is a huge mass of irrefutable evidence against it, and that evidence

increases in weight and cogency every time a theologian opens his mouth. All the

common arguments for it may be reduced to four. The first is logical and is to

the effect that it would be impossible to imagine God creating so noble a beast

as man, and then letting him die after a few unpleasant years on earth. The

answer is simple: I can imagine it, and so can many other men. Moreover, there

is no reason to believe that God regards man as noble: on the contrary, all the

available theological testimony runs the other way. The second argument is that

a belief in immortality is universal in mankind, and that its very universality

is ample proof of its truth. The answer is (a) that many men actually dissent,

some of them in a very violent and ribald manner, and (b) that even if all men

said aye it would prove nothing, for all men once said aye to the existence of

witches. The third argument is that the dead, speaking through the mouths of

gifted mediums, frequently communicate with the living, and must thus be alive

themselves. Unfortunately, the evidence for this is so dubious that it takes a

special kind of mind to credit it, and that kind of mind is far from persuasive.

The fourth and final argument is based frankly on revelation: the soul is

immortal because God hath said it is.

I confess that this last argument seems to me to be

rather more respectable than any of the others: it at least makes no silly

attempt to lug in the methods of science to prove a proposition in theology. But

all the same there are plenty of obvious holes in it. Its proponents get into

serious difficulties when they under-take to say when and how the soul gets into

the body, and where it comes from. Must it be specially created in each

in-stance, or is it the offspring of the two parent souls? In either case, when

does it appear, at the moment of conception or somewhat later? If the former,

then what happens to the soul of a zygote cast out, say, an hour after

fertilization? If the death of that soul ensues, then the soul is not immortal

in all cases, which means that its immortality can be certain in none: and if,

on the contrary, it goes to Heaven or Hell or some vague realm between, then we

are asked to believe that the bishops and archbishops who swarm beyond the grave

are forced to associate, and on terms of equality, with shapes that can neither

think nor speak, and resemble tadpoles far more than they resemble Christians.

And if it be answered that all souls, after death, develop to the same point and

shed all the characters of the flesh, then every imaginable scheme of post-mortem

jurisprudence becomes ridiculous.

The assumption that the soul enters the body at

some time after conception opens difficulties quite as serious, but I shall not

annoy you with them in this hot weather. Suffice it to say that it forces one to

believe either that there is a time when a human embryo, though it is alive, is

not really a human being, or that a human being can exist without a soul. Both

notions revolt me - the first as a student of biology, and the second as a

dutiful subject of a great Christian state. The answers of the professional

theologians are all inadequate. The Catholics try to get rid of the problem by

consigning the souls of the un-baptized to a Limbus Infantum which is neither

Heaven nor Hell, but that is only a begging of the question. As for the

Protestants, they commonly refuse to discuss it at all. Their position seems to

be that everyone ought to believe in the immortality of the soul as a matter of

common decency, and that, when one has got that far, the details are irrelevant.

But my appetite for details continues to plague me. I am naturally full of

curiosity about a doctrine which, if it can be shown to be true, is of the

utmost personal importance to me. Failing light, I go on believing dismally that

when the bells ring and the cannon are fired, and people go rushing about

frantic with grief, and my mortal clay is stuffed for the National Museum at

Washington, it will be the veritable end of the noble and lovely creature once

answering to the name of Henry.

Miracles

From the American Mercury, May, 1924, p. 61

Has it ever occurred to anyone that miracles may be

explained, not on the ground that the gods have transiently changed their rules,

but on the ground that they have gone dozing and forgotten to enforce them? If

they slept for two days running the moon might shock and singe us all by taking

a header into the sun. For all we know, the moon may be quite as conscious as a

poet or a realtor, and extremely weary of its monotonous round. It may long,

above all things, for a chance to plunge into the sun and end the farce. What

keeps it on its track is simply some external will - maybe not will embodied in

any imaginable being, but nevertheless will. Law without will is quite as

unthinkable as steam without heat.

Quod est Veritas?

From DAMN! A Book of CALUMNY, 1918, p. 95

All great religions, in order to escape absurdity, have

to admit a dilution of agnosticism. It is only the savage, whether of the

African bush or the American gospel tent, who pretends to know the will and

intent of God exactly and completely. “For who hath known the mind of the

Lord?” asked Paul of the Ro-mans. “How unsearchable are His judgments, and

His ways past finding out!” “It is the glory of God,” said Solomon, “to

conceal a thing.” “Clouds and darkness,” said David, “are around Him.”

“No man,” said the Preacher, “can find out the work of God.” ... The

difference between religions is a difference in their relative content of

agnosticism. The most satisfying and ecstatic faith is almost purely agnostic.

It trusts absolutely without professing to know at all.

The Doubter’s Reward

From DAMN! A Book OF CALUMNY, 1918, p. 96

Despite the common delusion to the contrary the

philosophy of doubt is far more comforting than that of hope. The doubter

escapes the worst penalty of the man of faith and hope; he is never

disappointed, and hence never indignant. The inexplicable and irremediable may

interest him, but they do not enrage him, or, I may add, fool him. This immunity

is worth all the dubious assurances ever foisted upon man. It is pragmatically

impregnable. Moreover, it makes for tolerance and sympathy. The doubter does not

hate his opponents; he sympathizes with them. In the end he may even come to

sympathize with God. The old idea of fatherhood here submerges in a new idea of

brotherhood. God, too, is beset by limitations, difficulties, broken hopes. Is

it disconcerting to think of Him thus? Well, is it any the less disconcerting to

think of Him as able to ease and answer, and yet failing?

Memorial Service

From

PREJUDICES: THIRD SERIES, 1922, pp. 232-37

First

printed in the Smart Set, March, 1922,

pp. 41-42

Where is the graveyard of dead gods? What lingering

mourner waters their mounds? There was a time when Jupiter was the king of the

gods, and any man who doubted his puissance was ipso facto a barbarian and an ignoramus. But where in all the world

is there a man who worships Jupiter today? And what of Huitzilopochtli? In one

year-and it is no more than five hundred years ago - 50,000 youths and maidens

were slain in sacrifice to him. Today, if he is remembered at all, it is only by

some vagrant savage in the depths of the Mexican forest. Huitzilopochtli, like

many other gods, had no human father; his mother was a virtuous widow; he was

born of an apparently innocent flirtation that she carried on with the sun. When

he frowned, his father, the sun, stood still. When he roared with rage,

earthquakes engulfed whole cities. When he thirsted he was watered with 10,000

gallons of human blood. But today Huitzilopochtli is as magnificently forgotten

as Allen G. Thurman. Once the peer of Allah, Buddha and Wotan, he is now the

peer of Richmond P. Hobson, Alton B. Parker, Adelina Patti, General Weyler and

Tom Sharkey.

Speaking of Huitzilopochtli recalls his brother

Tezcatilpoca. Tezcatilpoca was almost as powerful: he consumed 25,000 virgins a

year. Lead me to his tomb: I would weep, and hang a couronne des perles. But who knows where it is? Or where the grave

of Quitzalcoatl is? Or Xiehtecutli? Or Centeotl, that sweet one? Or Tlazolteotl,

the goddess of love? Or Mictlan? Or Xipe? Or all the host of Tzitzimitles? Where

are their bones? Where is the willow on which they hung their harps? In what

forlorn and unheard-of Hell do they await the resurrection morn? Who enjoys

their residuary estates? Or that of Dis, whom Caesar found to be the chief god

of the Celts? Or that of Tarves, the bull? Or that of Moccos, the pig? Or that

of Epona, the mare? Or that of Mullo, the celestial jackass? There was a time

when the Irish revered all these gods, but today even the drunkest Irishman

laughs at them.

But they have company in oblivion: the Hell of dead gods

is as crowded as the Presbyterian Hell for babies. Damona is there, and Esus,

and Drunemeton, and Silvana, and Dervones, and Adsalluta, and Deva, and Belisama,

and Uxellimus, and Borvo, and Grannos, and Mogons. All mighty gods in their day,

worshipped by millions, full of demands and impositions, able to bind and loose

- all gods of the first class. Men laboredd for generations to build vast temples

to them - temples with stones as large as hay wagons. The business of

interpreting their whims occupied thousands of priests, bishops, archbishops. To

doubt them was to die, usually at the stake. Armies took to the field to defend

them against infidels: villages were burned, women and children were butchered,

cattle were driven off. Yet in the end they all withered and died, and today

there is none so poor to do them reverence.

What has become of Sutekh, once the high god of the whole

Nile Valley? What has become of:

Resheph Anath Ashtoreth Nebo Melek Ahijah Isis Ptah Baal

Astarte Hadad Dagon Yau Amon-Re Osiris Molech?

All these were once gods of the highest eminence. Many of

them are mentioned with fear and trembling in the Old Testament. They ranked,

five or six thousand years ago, with Yahweh Himself; the worst of them stood far

higher than Thor. Yet they have all gone down the chute, and with them the

following:

Arianrod Morrigu Govannon Gunfled Dagda Ogyrvan Dea Dia

luno Lucina Saturn Furrina Cronos Engurra Belus Ubilulu U-dimmer-an-kia U-sab-sib

U-Mersi Tammuz Venus Beltis Nusku Aa Sin Apsu Elali Nuada Argetlam Tagd Goibniu

Odin Ogma Marzin Mars Diana of Ephesus Robigus Pluto Vesta Zer-panitu Merodach

Elum Marduk Nin Persephone Istar Lagas Nirig Nebo En-Mersi Assur Beltu

Kuski-banda Mami Zaraqui Zagaga Min-azu Qarradu Ueras

Ask the rector to lend you any good book on comparative

religion: you will find them all listed. They were the gods of the highest

dignity – gods of civilized peoples – worshipped and believed in by

millions. All were omnipotent, omniscient and immortal. And all are dead.

For

a large collection of more H. L. Mencken Essays:

Click here

for

Home

for

Home