|

THE SHORT EGYPTOLOGICAL CAREER OF MARGARET BENSON AND HER THREE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION IN THE TEMPLE OF THE GODDESS MUT AT KARNAK (1895-1897) |

Margaret Benson

PART I: THE BACKGROUND

|

THE SHORT EGYPTOLOGICAL CAREER OF MARGARET BENSON AND HER THREE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION IN THE TEMPLE OF THE GODDESS MUT AT KARNAK (1895-1897) |

PART I: THE BACKGROUND

(Author's note: In 1976 The Brooklyn Museum began an excavation campaign in the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at Karnak and in 1978 The Detroit Institute of Arts joined the excavation as a supporting institution. One of the first priorities of the work was a complete examination of all previous exploration and excavation in the precinct, particularly that of Margaret Benson carried out in 1895-7. References in this article to recent excavations are to the work of the Brooklyn group.) 1In the nineteenth century, Egyptian archaeology, as a male dominated occupation, was not prepared for Margaret Benson when, in 1895, she achieved the distinction of being the first woman to gain permission to conduct her own excavation in Egypt. A thirty year old semi-invalid of a distinguished English family, she had the rare good luck to ask for the concession to a site that seemed unimportant and a site that no one else wanted. It was assumed that even an woman amateur with no experience could do little harm at the nearly destroyed Temple of Mut, in a remote location south of the Amun precinct at Karnak. She worked there for only three seasons from 1895 to 1897 and she published The Temple of Mut in Asher in 1899 2 with Janet Gourlay, who joined her in the second season. In the introduction to that publication of her work she emphasized that it was the first time any woman had been given permission by the Egyptian Department of Antiquities to excavate; she was well aware that it was something of an accomplishment.

Our first intention was not ambitious. We were desirous of clearing a picturesque site. We were frankly warned that we should make no discoveries; indeed if any had been anticipated, it was unlikely that the clearance would have been entrusted to inexperienced direction. 3Margaret Benson was born June 16, 1865, one of the six children of Edward White Benson. Her father's career as an Anglican clergyman and educator was illustrious. He was first an assistant master at Rugby, then the first headmaster of the newly founded Wellington College.

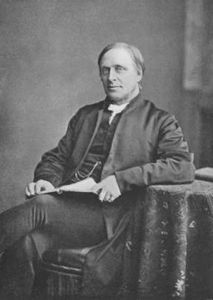

Archbishop Benson at two stages in his career

He rose in the service of the church as Chancellor of the diocese of Lincoln, Bishop of Truro and, finally, Archbishop of Canterbury. E. W. Benson was a learned man with a wide knowledge of history and a serious concern for the education of the young. He was also something of a poet and one of his hymns is still included in the American Episcopal Hymnal. Three of Margaret's brothers attained some degree of fame. Arthur Christopher, the eldest, was first a master at Eton and then at Magdalen College, Cambridge. A noted author and poet with an enormous literary output, he published over fifty books, most of an inspirational nature, but he was also the author of monographs on D. G. Rossetti, Edward Fitzgerald and Walter Pater. He helped to edit the correspondence of Queen Victoria for publication, contributed poetry to The Yellow Book, and wrote the words to the anthem "Land of Hope and Glory". Most important to the study of the excavator of the Mut Temple, he was the author of The Life and Letters of Maggie Benson, 4 a sympathetic biography which helps to shed some light on her short archaeological career.The third son of Edward White Benson was no less well know in English literary circles. Edward Frederick Benson was a popular novelist whose works have recently been revived. He also wrote several reminiscences of his family in which he included his sister and described his involvement in her excavations. He helped to supervise part of the work and he prepared the plan of the temple which was used in her eventual publication. His younger brother, Robert Hugh Benson, took Holy Orders in the Church of England, later converted to Roman Catholicism and was ordained a priest in that rite. He also achieved some fame as a novelist and poet and rose to the position of Papal Chamberlain. Hugh accompanied the family to Egypt in 1897 but did not participate in the excavation.

Arthur, Hugh and FredThese four male Bensons are included in every encyclopedia and biographical dictionary since the turn of the century, yet Margaret does not get a line, even as the daughter of her famous father. Her archaeological efforts are known only to specialists in the field of Egyptology. Her publication of the excavation is cited in every reference to the Temple of Mut in the Egyptological literature, but she is known to history as a name in a footnote and little else.

Margaret Benson was born at Wellington College during her father's tenure as headmaster. Each career advancement for him meant a move for the family so her childhood was spent in a series of official residences until she went to Oxford in 1883. She was eighteen when she was enrolled at Lady Margaret Hall, a women's college founded only four years before. One of her tutors commented to his sister that he was sorry Margaret had not been able to read for "Greats" in the normal way. He would have liked to have had her work compared to men of her own standing. 5 When she took a first in the Women's Honours School of Philosophy, he said, "No one will realize how brilliantly she has done." 6 Since her work was not compared to that of her male contemporaries, it would have escaped noticed.

In her studies she concentrated on political economy and moral sciences but she was also active in many aspects of the college. She participated in dramatics, debating and sports but her outstanding talent was for drawing and painting in watercolor. John Ruskin himself praised her work and invited her to study at his school. Her skill was so superior he thought she should be appointed drawing mistress if she remained at Lady Margaret Hall for any length of time.

Margaret was a serious scholar with serious concerns. She began a work titled "The Venture of Rational Faith" which occupied her thoughts for many years. Another of her writings was "Capital, Labor, Trade and the Outlook". Both of these are mentioned often by her brothers but they seem to have left little trace. From the titles alone they suggest a young woman who was deeply concerned with problems of society and the spirit and this preoccupation with the spiritual was to be one of her concerns throughout the rest of her life. In some of her letters from Egypt it is clear that she was attempting to understand something of the spiritual life of the ancient Egyptians, not a surprising interest for the daughter of a churchman like Edward White Benson.

In 1885, at the age of twenty, Margaret was taken ill with scarlet fever while at Zermatt in Switzerland. This is the first indication of a life of continuous bad health. By the time she was twenty-five she had developed the symptoms of rheumatism and the beginnings of arthritis. From then on her life was a series of journeys in search of cures or physical relief. She made her first voyage to Egypt in 1894 because the warm climate was considered to be beneficial for those who suffered from her ailments. Wintering in Egypt was highly recommended at the time for a wide range of illnesses ranging from simple asthma to "mental strain." Lord Carnarvon, Howard Carter's sponsor in the search for the tomb of Tutankhamun, was one of the many who went to Egypt for reasons of health. Like Margaret Benson, he also stayed on to pursue an amateur interest in archaeology.

On Margaret's first visit to Egypt in 1894 she arrived at Alexandria in January. After Cairo and Giza she went on by stages as far as Aswan and the island temples of Philae. She commented on the "wonderful calm" of the Great Sphinx, the physical beauty of the Nubians, the color of the stone at Philae, the descent of the cataract by boat, which she said was "not at all dangerous". By the end of January she was established in Luxor with a program of visits to the monuments set out.

This place grows on one extraordinarily. I don't feel as if I should have really had an idea of Egypt at all if I hadn't stayed here -- the Bas-reliefs of kings in chariots are only now beginning to look individual instead of made on a pattern, and the immensity of the whole thing is beginning to dawn -- and the colours, oh my goodness! You get to see them more every day.7Her letters from the first trip are full of details of the sights and sound of the country; the animals and birds, the little gossip concerning other visitors and tourists, occasional comments on ancient Egyptian religious beliefs and reactions to the contemporary Egyptians she encountered. A typical aside: "The children are very nice when they are not either lying or begging."

During her first visit she began a study of hieroglyphs and of Arabic. The ancient language and script she found fascinating but she was not as interested in reading classical Arabic. Her interest was maintained by the variety of animal and bird life for at home in England she had been surrounded by domestic animals and had always been keen on keeping pets. By the time her first stay ended in March, 1894, she had already resolved to return in the fall.

When Margaret returned to Egypt in November she had already conceived the idea of excavating a site and thus applied to the Egyptian authorities. She asked for permission to clear the Temple of Mut at Karnak but she was refused. Edouard Naville, the Swiss Egyptologist who was working at the Temple of Hatshepsut at Dier el Bahri for the Egypt Exploration Fund, wrote to Henri de Morgan, Director of the Department of Antiquities, on her behalf. Permission to excavate was granted at the beginning of January, 1895. From her letters of the time, it is clear that this was one of the most exciting moments of Margaret Benson's life because she was allowed to embark on what she considered a great adventure.

Margaret's physical condition at the beginning of the excavation was of great concern to the family. Her brother Fred (E. F. Benson) wrote about this at length.

Did ever an invalid plan and carry out so sumptuous an activity? She was wintering in Egypt for her health, being threatened with a crippling form of rheumatism; she was suffering also from an internal malady, depressing and deadly; a chill was a serious thing for her, fatigue must be avoided, and yet with the most glorious contempt of bodily ailments which I have seen, she continued to employ some amazing mental vitality that brushed disabilities aside, and, while it conformed to medical orders, crammed the minutes with such sowings and reapings as the most robust might envy.... All the local English archaeologists were , so to speak, at her feet, partly from the entire novelty of an English girl conducting an excavation of her own, but more because of her grateful and enthusiastic personality....8It should be remembered that the "English girl" was thirty years old when she began the excavation.Margaret Benson had no particular training to qualify or prepare her for the job but what she lacked in experience she more than made up for with her "enthusiastic personality" and her intellectual curiosity. In the preface to The Temple of Mut in Asher she said that she had no intention of publishing the work because she had been warned that there was little to find. She also said that if she had known what was to come of it she would have kept better records and "ordered many things differently." In 1901, after her work at the Temple of Mut was over, she wrote to her mother:

"Such a lot of times in my life I've been driven this way and that... things stopped just when I thought I was getting to them, or like Egyptology, opened just when I could do nothing else....".9She chose to excavate because it seemed a project of interest to her at a time when her ever-active mind needed stimulation and her health made it necessary to be in the warm climate of Egypt. As the work progressed over three seasons the obligation of the excavator to publish became obvious to Margaret Benson. In the introduction to The Temple of Mut in Asher acknowledgments were made and gratitude was offered to a number of people who aided in the work in various ways. The professional Egyptologists and archaeologists included Naville, Petrie, de Morgan, Brugsch, Borchardt, Daressy, Hogarth and especially Percy Newberry who translated the inscriptions on all of the statues found. Miss Katharine Gent (Mrs. Lea), 10 a Colonel Esdaile, 11 and Margaret's brother, Fred, helped in the supervision of the work in one or more seasons. Funding was obtained from a number of individuals including members of the Benson family.It is usually assumed that Margaret Benson and Janet Gourlay worked only as amateurs, with little direction and totally inexperienced help. It is clear from the publication that Naville helped to set up the excavation and helped to plan the work. Hogarth 12 gave advice in the direction of the digging and Newberry was singled out for his advice, suggestions and correction as well as "unwearied kindness." Margaret's brother, Fred, helped his inexperienced sister by supervising some of the work as well as making a measured plan of the temple which is reproduced in the publication.

Fred (E. F. Benson) was qualified to help because he had intended to pursue archaeology as a career, studied Classical Languages and archaeology at Cambridge, and was awarded a scholarship at King's College on the basis of his work. He organized a small excavation at Chester to search for Roman legionary tomb stones built into the town wall and the results of his efforts were noticed favorably by Theodore Mommsen, the great nineteenth century classicist, and by Mr. Gladstone, the Prime Minister (who was also an amateur archaeologist). E. F. Benson went on to excavate at Megalopolis in Greece for the British School at Athens and published the result of his work in the Journal of Hellenic Studies. His first love was Greece and its antiquities and it is probable that concern for his sister's health was a more important reason for him joining the excavation than an interest in the antiquities of Egypt. 13

It is interesting to speculate as to why a Victorian woman was drawn to the Temple of Mut. The precinct of the goddess who was the consort of Amun, titled "Lady of Heaven", and "Mistress of all the Gods", is a compelling site and was certainly in need of further exploration in Margaret's time. The site is somewhat deserted in appearance today, and was much more so in the 1890s. Its isolation and the arrangement with the Temple of Mut enclosed on three sides by its own sacred lake made it seem even more romantic. 14 When she began the excavation three days was considered enough time to "do" the monuments of Luxor and Margaret said that few people could be expected to spend even a half hour at in the Precinct of Mut. On her first visit to Egypt in 1894 she had gone to see the temple because she had heard about the granite statues with cats' heads (the lion-headed images of Sakhmet). The donkey-boys knew how to find the temple but it was not considered a "usual excursion" and after her early visits to the site she said that "The temple itself was much destroyed, and the broken walls so far buried, that one could not trace the plan of more than the outer court and a few small chambers". 15 The Precinct of the Goddess Mut is an extensive field of ruins about twenty-two acres in size, of which Margaret had chosen to excavate only the central structure. Connected to the southernmost pylons of the larger Amun Temple of Karnak by an avenue of sphinxes, the Mut precinct contains three major temples and a number of smaller structures in various stages of dilapidation. She noted some of these details in her initial description of the site, but in three short seasons she was only able to work inside the Mut Temple proper and she cleared little of its exterior.

The known history of interest in this site began around 1760 when an Arab sheikh excavated statues of Sakhmet for a Venetian priest. Serious study of the temple complex was started at least as early as the expedition of Napoleon at the end of the eighteenth century when artists and engineers attached to the military corps measured the ruins and made drawings of some of the statues. During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the great age of the treasure hunters in Egypt, Giovanni Belzoni carried away many of the lion-headed statues and pieces of sculpture to European museums. Champollion, the decipherer of hieroglyphs, and Karl Lepsius, the pioneer German Egyptologist, both visited the precinct, copied inscriptions and made maps of the remains.16 August Mariette had excavated there and believed that he had exhausted the site. Most of the travelers and scholars who had visited the precinct or carried out work there left some notes or sketches of what they saw and these were useful as references for the new excavation. Since some of the early sources on the site are quoted in her publication, Margaret was obviously aware of their existence. 17

On her return to Egypt at the end of November, 1894, she stopped at Mena House hotel at Giza and for a short time at Helwan, south of Cairo. Helwan was known for its sulphur springs and from about 1880 it had become a popular health resort, particularly suited for the treatment of the sorts of maladies from which Margaret suffered. When she got to Luxor she was greeted by the locals as an old friend. People at every turn asked if she remembered them and her donkey-boy almost wept to see her.

"On January 1st, 1895, we began the excavation" -- with a crew composed of four men, sixteen boys (to carry away the earth), an overseer, a night guardian and a water carrier. The largest the work gang would be in the three seasons of excavation was sixteen or seventeen men and eighty boys, still a sizable number. Before the work started Naville came to "interview our overseer and show us how to determine the course of the work". A good part of Margaret's time was occupied with learning how to supervise the workmen and the basket boys. Since her spoken Arabic was almost nonexistent, she had to use a donkey-boy as a translator. It would have been helpful if she had had the opportunity to work on an excavation conducted by a professional and profit from the experience but she was eager to learn and had generally good advice at her disposal so she proceeded in an orderly manner and began to clear the temple.

On the second of January she wrote to her mother:

I don't think much will be found of little things, only walls, bases of pillars, and possibly Cat-statues. I am already in treaty for a tent. I shall feel rather like --Massa in the shade would lay While we poor niggers toiled all day -- for I am to have a responsible overseer, and my chief duty apparently will be paying. I find that I am beginning to be considered in the light of an Egyptologist. 18She is described as riding out from the Luxor Hotel on donkey-back with bags of piaster pieces jingling for the Saturday payday. She had been warned to pay each man and boy personally rather than through the overseer to reduce the chances of wages disappearing into the hands of intermediaries. The workmen believed that she was at least a princess and they wanted to know if her father lived in the same village as the Queen of England. When they sang their impromptu work songs (as Egyptian workmen still do) they called Margaret the "Princess" and her brother Fred the "Khedive".

PART II: THE EXCAVATIONS The clearance was begun in the northern, outer, court of the temple where Mariette had certainly worked. Earth was banked to the north side of the court, against the back of the ruined first pylon but on the south it had been dug out even below the level of the pavement. Mariette's map is inaccurate in a number of respects suggesting that he was not able to expose enough of the main walls.

First Stone Gateway After Clearance by the Brooklyn-Detroit Excavations

At the first (northern) gate it was necessary for Margaret Benson to clear ten or twelve feet of earth to reach the paving stones at the bottom. In the process they found what were described as fallen roofing blocks, a lion-headed statue lying across and blocking the way, and also a small sandstone head of a hippopotamus. In the clearance of the court the bases of four pairs of columns were found, not five as on Mariette's map. After working around the west half of the first court and disengaging eight Sakhmet statues in the process, they came on their first important find. Near the west wall of the court, was discovered a block statue of a man named Amenemhet, a royal scribe of the time of Amenhotep II. The statue is now in Egyptian Museum in Cairo 19 but Margaret was given a cast of it to take home to England. When it was discovered she wrote to her father:My Dearest Papa,The government had appointed an overseer who spent his time watching the excavation for just such finds. He reported it to a sub-inspector who immediately took the block statue away to a store house and locked it up. An appeal was made to Daressy who was kind enough to reverse the decision. He said it was hard that Margaret should not have "la jouissance de la statue que vous avez trouve" and she was allowed to take it to the hotel where she could enjoy it until the end of the season when it would become the property of the museum. The statue had been found on the pavement level, apparently in situ, suggesting to the excavator that this was good evidence for an earlier dating for the temple than was generally believed at the time. The presence of a statue on the floor of a temple does not necessarily date the temple, but many contemporary Egyptologists might have come to the same conclusion.

We have had such a splendid find at the Temple of Mut that I must write to tell you about it. We were just going out there on Monday, when we met one of our boys who works there running to tell us that they had found a statue. When we got there they were washing it, and it proved to be a black granite figure about two feet high, knees up to its chin, hands crossed on them, one hand holding a lotus. 20One visitor to the site recalled that a party of American tourists were perplexed when Margaret was pointed out to them as the director of the dig. At that moment she and a friend were sitting on the ground quarreling about who could build the best sand castle. This was probably not the picture of an "important" English Egyptologist that the Americans had expected. As work was continued in the first court other broken statues of Sakhmet were found as well as two seated sandstone baboons of the time of Ramesses III. 21 The baboons went to the museum in Cairo, a fragment of a limestone stela was eventually consigned to a store house in Luxor and the upper part of a female figure was left in the precinct where it was recently rediscovered. The small objects found in the season of 1895 included a few coins, a terra cotta of a reclining "princess", some beads, Roman pots and broken bits of bronze. Time was spent repositioning Sakhmet statues which appeared to be out of place based on what was perceived as a pattern for their arrangement. Even if they were correct they could not be sure that they were reconstructing the original ancient placement of the statues in the temple or some modification of the original design. In the spirit of neatness and attempting to leave the precinct in good order, they also repaired some of the statues with the aid of an Italian plasterer, hired especially for that purpose.

Margaret was often bed ridden by her illnesses and she was subject to fits of depression as well but she and her brother Fred would while away the evenings playing impromptu parlor games. For a fancy dress ball at the Luxor Hotel she appeared costumed as the goddess Mut, wearing a vulture headdress which Naville praised for its ingenuity. The resources in the souk of Luxor for fancy dress were nonexistent but Margaret was resourceful enough to find material with which to fabricate a costume based, as she said, on "Old Egyptian pictures."

The results of the first season would have been gratifying for any excavator. In a short five weeks the "English Lady" had begun to clear the temple and to note the errors on the older plans available to her. She had started a program of reconstruction with the idea of preserving some of the statues of Sakhmet littering the site. She had found one statue of great importance and the torso of another which did not seem so significant to her. Her original intention of digging in a picturesque place where she had been told there was nothing much to be found was beginning to produce unexpected results.

The Benson party arrived in Egypt for the second season early in January of 1896. After a trip down to Aswan, they reached Luxor around the twenty-sixth and the work began on the thirtieth. That day Margaret was introduced to Janet Gourlay who had come to assist with the excavation. The beginning of the long relationship between "Maggie" Benson and "Nettie" Gourlay was not signaled with any particular importance. Margaret wrote to her mother: "Yesterday morning (January 30), Jeanie (Lady Jane Lindsey) came with me, and a Miss Gourlay who is going to help...". By May of the same year she was to write (also to her mother): "I like her more and more -- I haven't liked anyone so well in years". Miss Benson and Miss Gourlay seemed to work together very well and to share similar reactions and feelings. They were to remain close friends for much of Margaret's life, visiting and travelling together often. Their correspondence reflects a deep mutual sympathy and Janet was apparently much on Margaret's mind because she often mentioned her friend in writing to others. Little is know about Janet Gourlay today. After her relationship with Margaret Benson she faded into obscurity and even her family has been difficult to trace, although a sister was located a few years ago.

For the second season in 1896 the work staff was a little larger, with eight to twelve men, twenty-four to thirty-six boys, a rais (overseer), guardians and the necessary water carrier. More constant supervision was given to the work as the nature of it demanded. With the first court considered cleared in the previous season, work was begun at the gate way between the first and second courts. An investigation was made of the ruined wall between these two courts and the conclusion was drawn that it was "a composite structure" suggesting that part of the wall was of a later date than the rest. The wall east of the gate opening is of stone and clearly of at least two building periods while the west side has a mud brick core faced on the south with stone. Margaret thought the west half of the wall to be completely destroyed because it was of mud brick which had never been replaced by stone. She found the remains of "more than one row of hollow pots" which she thought had been used as "air bricks" in some later rebuilding. It is now believed that this wall exhibits four construction phases. Originally built of mud brick, like many of the structures in the Precinct of Mut, the south face of both halves of the wall was sheathed with stone one course thick no later than the Ramesside Period. During the Ptolemaic Period the core of the east half of the mud brick wall was replaced with stone but the Ramesside sheathing was retained. Sometime after the temple fell into disuse the remaining mud brick half on the west was partly hollowed out and used as a dwelling or magazine (which may account for the rows of pots Margaret thought to be rebuilding).