|

Signals

Diversions of Ruark Lewis

…"mnemonic devices which carry

something close to language, but which do not speak for themselves."

Philip Jones, Raft of Allusions [Jones,

1999]

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round

it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

Wallace Stevens, 'Anecdote of the Jar'

I asked Ruark Lewis if he had written anything on his signals and

decoys; and as he said he did not, I decided to write at my own risk to

misinterpret them, but the misinterpretation is what they are for anyway.

We cannot let things speak for themselves anymore. Since Heidegger's

project, salvation has been whispering, but we have proved to be too poor

listeners to the whispers. It is too late for us to learn to listen and to

read, because we will die tomorrow, because we will die today, because we are

dying every minute, with the strings and threads of the fabric of simulated

reality pulling and vigorously mesmerizing the limbs of our empty shells.

We may need to surrender, because the revolution failed. The only

significant revolutionary project, Marxism, was a negative mold of industrial

capitalism. The modern communist countries are megaliths at work, living

fossils of the 19th-century capitalist economy and politics. Maybe that's what

makes today the dialog between the Western neo-conservatism and China

relatively natural.

The revolution has failed. Rebellion without revolution is longing for the

womb, for the re-creation on the earth without form, and void, for the

original undifferentiated state mistaken for pristine. It is animal in us.

(What is better: be animal or dead?) We may need to surrender. It is

impossible to build a new world from inert material, because exactly this idea

created capitalism, while such a material never existed anyway.

There is no material apart from the encounter with material. We make sense

of the encounter with material. The material makes sense of the encounter with

us. It does not bear in itself any sense of itself, but it always bears in

itself some sense of us. The encounter with material is the horizon of

meaning. The encounter with material means matching.

On the other hand, moving along the surface, along the row, matrix, or

sequence of objects or images means pointing (positioning oneself); referring

(moving from one position to another); and selection (the representation of

our special position as an observer supposedly wielding power over things by

assigning differential value to them).

Selection can be done only among many things which are similar enough to

the extent to allow their substitution, i.e. symbolic exchange, but slightly

different to produce an excess of value, so that the skillful exchange would

be profitable and thus motivated.

Therefore, the surface of any material, the surface (in fact, a fabric of

surfaces) we are embedded into is a cultural, economical, aesthetic, or sexual

system of simulacra.

Once we start appreciating certain things, they quickly become a valuable

currency ("value" is just another word for "appreciation")

and it immediately plugs them into the cycle of symbolic exchange. The system

of simulacra or capitalism even does not need to adapt to protect itself from

new dangers. By appreciating something, we reproduce a simulative pattern:

Baudrillard [Baudrillard 1976] shows how graffiti in the American cities

could destroy the simulative sign code. He gives it as an example of

reclaiming oneself from the system. However, his hermeneutics of graffiti

assigns symbolic value to it. No surprise that since long ago graffiti is

nicely appropriated by the capitalist culture: its revolutionary energy

discharged into macho or teen vitality; works of Banksy are traded at

Sotheby's; and academic works on the subject including Baudrillard's are selling well.

The attempt to turn one's head away from the simulacra and get through to

the things themselves fails for the same reason. Say, the popular history of

Zen in the West is a joke.

Therefore, finding "true values" or "true beauty"

(whatever it means) to defy the simulated ones and move beyond the latter

becomes contradiction in terms. Once they are proven and recognized as such,

by that very fact they get involved into symbolic exchange. And you cannot

keep them secret, either. Whatever cannot be Googled does not exist.

We need to surrender, which means the dubious courage to stay and work

inside of the system of simulacra, be part of it, enjoy it (as many find it

enjoyable), and perhaps make a decent living out of it. The strange part is

that the art, which used to be about something like beauty, suddenly would

acquire another weird quality that has somehow to be aesthetic (as long as it

is about feeling), and yet does not fit into the scale between the beautiful

and ugly (as long as the oppositions of aesthetics are concerned).

The encounter with the material, matching, may tell us more about this

strange feeling.

Matching is not just random or passive conformity of two things, like two

pieces of a broken jar. Matching is an action (of course, it puts matching in

a dangerous relationship with the activism of simulated reality), it is

purposeful and it matches its purpose. Therefore, something that matches is a

tool.

Tools are meant for something. They have to refer to some activity during

which they play their role as tools. As tools necessarily refer to something,

they are signs.

They don't have any resemblance of their referent, they refer by their

matching quality: a hammer matches nails (and hand), the aerodynamic outline

of a car matches streams of air, alphabet somehow matches sounds.

We can feel the tool-ness of tools, their matching quality itself, when

their referent is absent. Then, their quality suddenly remains lingering and

gets strangely exposed. In daily life, we have this weird and often charming

feel, when the tools are at rest: a shovel in the shed, weapons in the

storage, objects use of which we don't even know on the shelf in the shop,

words of foreign language, conceptual art work with its title and description

missing.

Heidegger places tools and utilitarian pieces of craft between nature and

work of art. Nature and work of art just stand by themselves, while tools and

materials don't belong to themselves: "Craft-ness of a crafted thing (das

Zeugsein des Zeuges) consists in its use." [Heidegger, 1960]. They always

are about something else.

Leaving tools at rest allows them to stand and extend a bridge

between the nature and art. But as I tried to show, leaving them at rest is

different from trying to turn "back to things as they are".

(Still, what creates such a special aesthetic experience? To make a good

tool, we need to make sure that it is placed exactly under the horizon of

meaning. This gives the tool such a power. Say, by moving speech

representation below the horizon of meaning, i.e. decomposing the speech

exactly until the point where its meaning first disappears revolutionized

circulation of knowledge and defined the ways of humanity in the West: first

phonetic alphabets - splitting words into sounds; Guttenberg's invention -

splitting words into letters, hypertext - marking and mapping text as abstract

structure, splitting text into formally interrelated tokens.)

The tool-ness of tools gets revealed the better the more they are devoid of

anything what does not belong to their function, but then their referent also

is absent. This kind of experience of tools is experience of signs with the

absent meaning. Their own material qualities are at their best to serve their

reference, but the reference is concealed, unknown (as for letters of a

foreign language), or destroyed (like a metaphor of shipwreck in Ruark Lewis's

Raft [Carter, Lewis, 1999]), we catch the tools exposed. This is the most

bizarre, surreal feeling of a peaceful presence of something that is right

here, but cannot be revealed or described without destroying it, because

description presumes words and signs working, referring to each other, telling

the story, whereas here the feeling is achieved by the total removing of the

referent and thus reclaiming the sign.

In the Raft, the text is irreversibly ciphered in the assemblage of the

debris of a symbolic shipwreck (debris of symbols, as Raft itself is perfectly

organized for its purpose, salvation). It refers to a particular text, but

it's impossible to reconstruct to which one, also showing that the entropy in

language cannot go beyond certain critical point, at which language suddenly

acquires (or just exposes) new generative qualities. It represents the crash

of the missionary journey of the Western discourse possessed and driven by the

power of logos [Carter, Lewis, 1999]. The ship hits the boundary and

collapses; and its transformation into the Raft is its salvation by

de[con]struction.

Benjamin wrote:

"The translation of the language of things into that of man is not

only a translation of the mute into the sonic; it is also the translation of

the nameless into name. ... It would be insoluble were not the name-language

of man and the nameless one of things related in God and released from the

same creative word, which in things became the communication of matter in

magic communion..." [Benjamin 1916, p. 325]

The whole project of Raft is well-pronounced by the authors as the work of

translation and transcription [Carter, Lewis, 1999]. Here the genetive seems

to emphasize as the goal of their work not the result of translation, but the

translation process, i.e. it's the toolness, being-at-hand, being in the gap

between "the mute" and "the sonic", and then between one

sonic and another, preserving this interplay by stepping back from the

temptation of named (as it adds knowledge [Benjamin 1916, p. 326]) back - but

not the whole way back - to the nameless (God did the same, creating the world

by logos, but giving it nameless to the Man for naming [Benjamin 1916, p.

326]).

Ruark Lewis, Blue water drawing, transcriptions of Die Regen-Manner (atua kwatja) und der Regebogen (Mbulara)

from Carl Strehlow, Die Aranda-und Loritja-Stamme in Zentral-Australien, 1907;

fragment, 1997, oil on canvas, 50 x 400cm. Photo © Ruark Lewis

Part of the

Raft project, the painting transcribes the songs into a multilayered text,

concealing and salvaging them: "... in a period of visual saturation to

have its legibility reside in its resistance to instant translation and

consumption" [Carter, Lewis 1999, p.

139]

Thus, in Lewis's works half of the way has been made to the toolness of the

language, its being-at-hand.

Tools always are meant to be used, but their usage immediately includes

them into the chain of symbolic transformations in materials, signs, and

social circulation depending on their function. Breaking this chain gets their

basic consumption cycle suspended.

However, once tools go out of use, they assume the charm of patina; of

their texture; their connotations of a stable, tranquil, or traditional; their

story-telling. Without mentioning that stability and tradition presume

repetitiveness, which is immediately connected to the signs and the

circulation of ideal things [Derrida 1967], the nostalgic and aesthetic

qualities of old mass-crafted objects are a perfect selling point, which

includes them at once into the economics of appreciation and exchange.

Ironically, the best market place for their uniqueness is a simulated system

in its purest: Internet trading.

Thus, to achieve the unique suspended feel of the material and tool-ness,

we need to break the consumption chain of higher order - or even of the

highest one, as the aesthetic consumption is self-referent. Neither discursive

nor aesthetic means will work. Therefore, we need a gesture.

Lewis's installations feature loud sounds and bright objects. Can some of

them be examples of such a gesture? Probably, no, if they are perceived, in

the modernist manner, as wake-up calls or koan-like acts. Instead, they

are a post-modern maneuver, which Lewis calls signals (or decoys).

The rest of the installation may (or better, has to be) be very discreet,

but signals in it always attract attention (unless the whole piece offers a system

of signals, simulacra simulated). They grab us and without hesitation start

telling the story or even give us instructions. It may be brightly painted

picturesque rocks or small striped plaster sculptures placed here and there; or a collection of old pictures

from newspapers, whose captions play the role of signals, explaining why such

and such photograph was taken; or bright posters with trite sayings (Silence

is Gold). Lately, Lewis's favourites are objects covered with red and white

stripes. He calls them "municipal colours" and they are meant to map

and demarcate in the clear neighbourhood-style manner.

Ruark

Lewis, Log. © Ruark Lewis

Everything that could connect the logs to

their nature: their roots, texture of wood, signs of decay - is removed or

hidden. Instead, they are converted into signals, which, if put in an

installation or a forest, would divert from the "real" thing and

guide us into a comfortably mapped social space, thus playing the role of

drainage for our sign-making activism.

Ruark

Lewis, A Rock. © Ruark Lewis

The painted

rock here is not the Argument [Andrews 1999] of the scene. It has not

"made wilderness 'no longer wild'" [ibid] by offering an

interpretation of an urban corner and ephasizing the rich texture of its

materials. Instead, it absorbs and drains away the signifying capabilities of

the place.

As long as they tell stories or demarcate, the signals are ready for

consumption in striking contrast with other parts of Lewis's works that

carefully conceal the text right below the horizon of meaning. This is

suspicious. Signals are not meant to misguide or deceive, though. They are

bright in colour and pleasant in shape, like the modern medicine. And their

action is therapeutic: cooling us down and distracting us from the things on

which we could not concentrate anyway. (Could they be called placebo,

instead?) Their only role is to divert us from something, to take, like a dog

for a walk, the part of ourselves that cannot help following all the

tantalizing aromas at the backyard of logos.

Ruark

Lewis, An Index of Silence (fragment). © Ruark Lewis

Often parts of

audio-visual installations and performances, the banners with the trite

sayings relieve the viewer's anxiety, when the rational grounds of the place

are carefully removed or concealed.

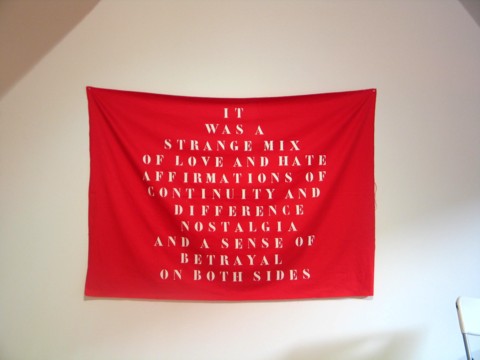

Ruark

Lewis, Quote. © Ruark Lewis

Quote is a pre-canned story, which

conveniently restores time and causal sequences, containing them from spilling

over into the rest of the installation.

As we cannot resist our sign-making activism anyway, signals are a drainage

fixture, discharging it back to system of simulacra. However what they leave

behind are not just "things as they are" removed from the

consumption chain. As they take over the task of bearing meaning, they thus

help dereference words or objects and restore their senseless tool-ness.

Signals as a maneuver are simulation of simulacra. Perhaps, the beauty

itself is a signal. It most fully (and, well, beautifully) diverts us to the

simulative rhythm and pulsation, concealing and preserving things (which

already cannot even be called things), saving us from ourselves, and

letting us partake of we don't know what.

Appendix.

Decoys of Fairytale

On

Ai Weiwei's Fairytale

I would like to show how the concept of signals could be used as an

analytical tool for a work of art, using Ai Weiwei's Fairytale, a

monumental project, a part of Documenta in Kassel, Germany, 2007.

I won't discuss the aspects of Ai Weiwei's work related to politics or

power, not because they are irrelevant, but because they are too important

for his projects.

Fairytale, as it is represented in a three-hour documentary, consisted in

selecting 1001 people randomly picked from various, sometimes most remote,

places in China and bringing them together for a few week to Kassel, Germany,

placing them in a dormitory, a re-designed warehouse with small regular

cubicles separated by light curtains. Some of the people were art students

from Shanghai, but many others had little experience of life even outside of

their village.

The Chinese were supposed to experience Kassel, a typical German city of

some 200 thousand people. With their little exposure to other cultures, all

kinds of emerging cultural and social effects and encounters were expected.

The first half of the documentary shows the selection process with the most

insightful episodes from daily life in China and beautiful shots.

The second part is about preparing the arrival of the 1001. Besides, we see

a massive timber construction built for the event out of the re-used old

Chinese timber. The construction hardly had been mentioned in the first half

of the film, which was meant to explicate the ideas of the project.

Then only a very short footage of the event itself is shown, followed by

brief interviews with the audience.

Strangely, we see the slow and monumental development of the project in

China, assembling and gathering lives of most unlikely people to the focal in

Kassel. This culmination appears to be elusive, though. All the preparations,

conceptually, aesthetically, and anthropologically rich and logistically

immensely laborious result in nothing. Moreover, Ai Weiwei explains that 1001

was chosen to symbolize uniqueness of each participant, expressing it in the

formula 1=1000. However, any personal touch is completely omitted, when the

event itself is shown. We see so little that we are inclined to think that the

whole idea failed.

However, most probably, Ai Weiwei gives us a hint that the failure is not

the case, when in the first interview with participants, two older Chinese

ladies, in the very beginning of the film he says to them (and to us): there

will be no show, no gala concert, no beauty pageant.

The matrix of 1001 individual lives creates a silent and concealed texture,

text and (wen in Chinese means "text" with etimology of

"texturized surface", "surface covered with traces", as

well as "culture"). They

are placed in a matrix as characters (in all the senses), first, of the selection process, the paperwork,

roster, and arrangements to take them to out of China, suspend - achieve epochè

of - the flow of

their lives, preserving their quality of human characters; and then into the concealed,

physically veiled matrix of the improvised dormitory in Kassel, which does not

have the structure of Chinese-styled totalitarian barracks or a Western

panopticon or glass house. The dividing unbleached curtains, moving and

waving, rather remind empty calligraphic paper scrolls. The texture,

text of the 1001 is deliberately hidden.

The mentioned timber structure apparently becomes one of the main visual attractions on

the site in Kassel, while very little is said about the individual experiences

of the 1001 people, which had been the centre of the project. The structure is

prominent, reminiscent of the Chinese culture and spirituality (the void in the

middle of the structure has the negative shape of a temple or a traditional

pavillion). The object seems

to be there to - intentionally or not - distract viewers' attention from the

1001, leave them alone.

The structure is

allusive not only to a temple, but also to a watchtower, to the administrative

demarcation, both in space and time; and telling thousands of stories.

However, it is not conceptually connected with the presence of the 1001

participants, but rather distracts the attention from them, while the audience

still disturbingly feels their unexplained and unveiled presence.

In the middle of the event, after a heavy rain, the structure collapses and

the artist decides not to restore it, supposedly because "the nature has

done something more beautiful than a human could do". However,

apparently, after the collapse, its story acquires unexpected continuation.

This watchtower is meant to be watched and thus, drain the aesthetisized

attention from the carefully shaped and concealed textual human matrix. This

is exactly how Lewis's signals work, and I think, it is a magnificent

example of a signal.

References

[Andrews 1999] Malcolm Andrews, Landscape and Western Art - Oxford

University Press, 1999.

[Baudrillard 1976] Jean Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death - Sage,

1993.

[Benjamin 1916] Walter Benjamin, On Language as Such and on the Language of

Man, in Walter Benjamin, Reflections. Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical

Writings. Schocken Books, New York, 1989.

[Carter, Lewis 1999] Paul Carter, Ruark Lewis, Depth of Translation - The

Book of Raft. 1999.

[Derrida 1967] Jacques Derrida, La voix et le phenomène:

introduction au problème du signe dans la phenomenology de Husserl. -

Presses Universitaires de France, 1967.

[Heidegger 1960] Martin Heidegger, Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes.

[Jones 1999] Philip Jones, A Raft of Allusions in [Carter, Lewis, 1999]

|

|