SUCH CHEMICAL INCREASES can be accommodated somehow, over

time. Earth has plenty of that, but do we? The current overloading has

the potential to alter life on this planet. Physically, our bodies may

already be showing the stress.

Take lead, for example. Most of us do, from paint, plumbing, and principally

automobile exhausts, despite reductions in the lead content in gasoline.

Getting the lead out

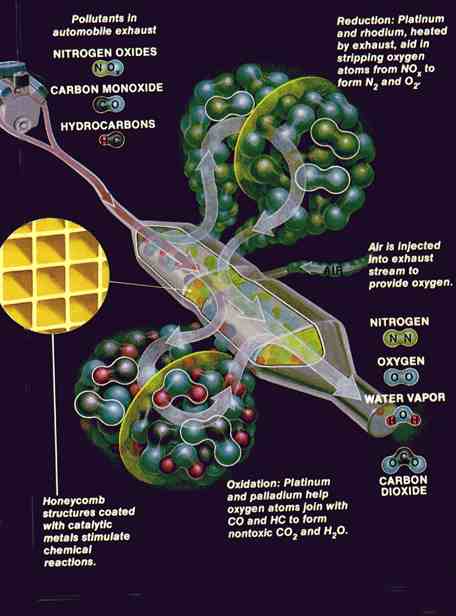

USING unleaded gasoline pays off in three ways: It keeps lead from poisoning the air, reduces maintenance, and allows a catalytic converter (right) to do its job. Installed on new cars sold in the U.S. since 1975, converters eliminate 90 percent of carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons and now great- ~ ly reduce nitrogen oxides. But only a few tankfuls of leaded gas can destroy converter effectiveness.

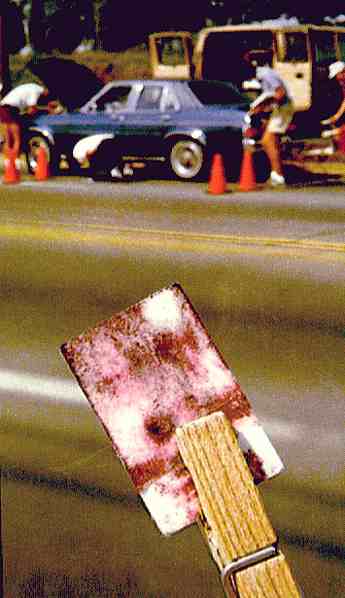

One in ten cars in the U.S. is thought to use leaded gas illegally because

it costs less. A tank opening (below right) has been enlarged to admit

a leaded gas nozzle.

Telltale pink on treated paper (below) reveals lead in car exizaust

checked during an annual survey by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Humanity releases many other elements to the air -- mercury, chromium, vanadium, selenium, arsenic. As with lead (and radiation from such incidents as the Chernobyl disaster) man's concentrated effluents often pose more danger than those from nature.

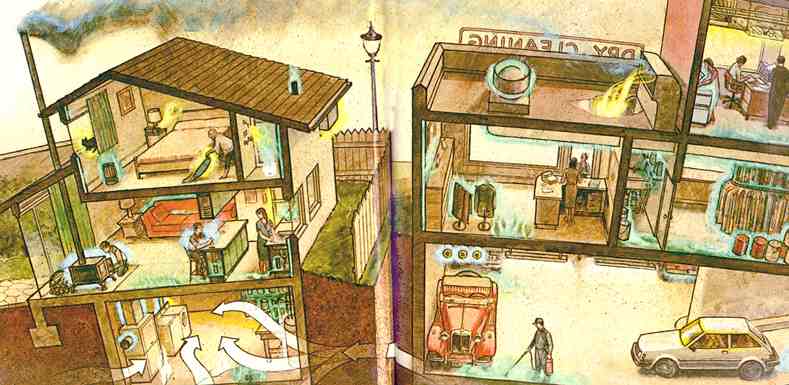

OUR MISTAKES are costly. Americans spend more than ten billion dollars

a year on medical problems caused by outdoor pollutants. Researchers now

suggest that gas and wood-burning stoves exude harmful compounds inside

buildings. These indoor pollutants, along with cigarette smoke, asbestos,

toxics released from building materials, and radon gas trapped by tight

insulation, may exact an annual health bill of a hundred billion dollars.

The enemy within

HERE'S no place like

home - or the office - for contaminated air. Pollution levels indoors,

especially in buildings that have been "tightened" for energy conservation,

can be ten times higher than those outdoors.

HERE'S no place like

home - or the office - for contaminated air. Pollution levels indoors,

especially in buildings that have been "tightened" for energy conservation,

can be ten times higher than those outdoors.