previous page next

page

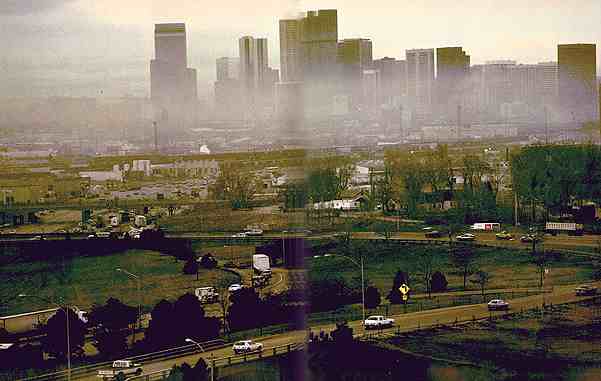

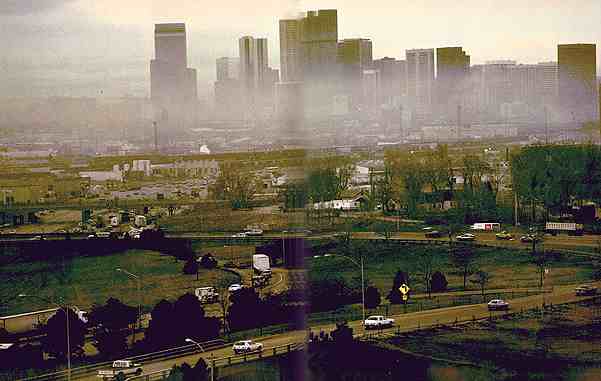

An unwelcome guest, Denver's "brown cloud" of smoke and smog

returns to the city each winter as heavy, cold air holds pollutants close

to the ground. The cloud's dismal color is created by sunlight reflected

off dustlike particles of wood smoke, diesel exhaust, and factory emissions.

From mid-November to mid-January, when atmospheric inversions often occur

here, Denver also suffers the nation's highest concentration of carbon

monoxide. To combat this problem, motorists during the past three years

have been asked not to drive on one working day a week, using a voluntary

system of rotation based on license plate numbers.

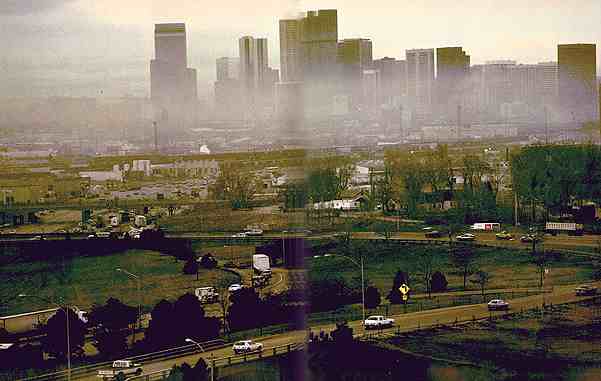

An unwelcome guest, Denver's "brown cloud" of smoke and smog

returns to the city each winter as heavy, cold air holds pollutants close

to the ground. The cloud's dismal color is created by sunlight reflected

off dustlike particles of wood smoke, diesel exhaust, and factory emissions.

From mid-November to mid-January, when atmospheric inversions often occur

here, Denver also suffers the nation's highest concentration of carbon

monoxide. To combat this problem, motorists during the past three years

have been asked not to drive on one working day a week, using a voluntary

system of rotation based on license plate numbers.

Trapped inside the combustion chamber instead of being released

into the atmosphere, coal ash forms a crust of slag inside a burner developed

by TRW, Inc. As much as 90 percent of the ash is caught by the burner system,

which also reduces emissions of nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides. The

system was designed to adapt gas or oil furnaces to burn powdered coal.

REDUCING the emissions of sulfur dioxides by half in this country,

using current technology, could require refitting large power plants with

flue-gas scrubbers.

The cost has been estimated at two to seven billion dollars a year,

for a total of 50 billion dollars over a decade. Who would pay for it?

Would it be power plants like those of the Ohio Valley, source of much

of this nation's sulfur dioxides? Or should the entire country pay through

an electrical usage tax, which would mean the polluter, polluted, and the

pristine share equally in the cost?

Perhaps Midwest plants should switch to low-sulfur coal mined in the

West. But that would idle 20,000 or more miners in Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky,

and West Virginia.

And what if that multibillion-dollar solution is the wrong one, outdated

the moment it is completed? "Technology is already available to burn fuel

more cleanly and efficiently, and within 15 or 20 years many existing plants

will be ready for retirement," admitted Dr. Mohnen.

Can the environment wait 20 years for better technology?

"Not at current emission levels," he replied, "but perhaps with conservation.

A 20 percent reduction in fossil fuel use is possible, through conservation

measures for automobiles and electric power users."

For the past half decade the U.S. government has answered calls for

controls on industrial emissions by saying more research was needed. In

early 1986 a joint U.S.-Canadian report called for a five-year industrial

emission control project costing five billion dollars. The report heartened

some Canadians; others remained skeptical that the U.S. would appropriate

the money in an era of tight budgets. So far, it has not.

In the U.S., acidification has long been seen as a problem of the eastern

states, but the West may also be vulnerable. Many eastern soils are underlain

with limestone and contain calcium carbonate that can neutralize acids.

Western alpine soils are commonly on top of granite, which provides little

neutralizing alkalinity. So far no significant changes in western acidity

have been detected, but increased exposure to power plants, smelters, and

motor vehicles could change that picture rapidly.

German trees have shown how rapid that change can be. The now

familiar signs of German forest dieback were noticed in the 1970s in the

black Forest. By 1986 more than half the nation's trees were afflicted.

"German forests as we know them may never exist again in our lifetime,"

said forest historian Dieter Deumling.

Elsewhere, witnesses in several eastern European countries, heavy users

of high-sulfur coal, report whole forests turned to stump-studded meadows.

Tree losses on Swiss Alpine slopes have been blamed for a rash of avalanches,

some of them fatal.

The possibility of fatalities by air pollution spurred Japan to action.

Two decades ago economic and industrial expansion had spawned a dangerous

success. From cities around Tokyo Bay came nightmarish images of citizens

wearing masks, breathing from oxygen vending machines.

"Around 1970 children were collapsing on school playgrounds from the

effects of photochemical smog, and there were numerous victims of a respiratory

disease known as Yokkaichi asthma," I was told by Kazuo Matsushita, deputy

director of the planning division in Japan's environmental agency.

Facing me across a table in a government building in Tokyo was a battery

of Japanese bureaucrats. At 35, Mr. Matsushita was the eldest. Ties loosened,

shirt sleeves rolled above their elbows, they exuded the same kind of energy

with which the nation has attacked world auto and electronic markets.

"The public was clamoring for cleaner air," said Mr. Matsushita. The

government offered tax breaks to companies that met clean-air standards

early. And the industrial community was reminded of the benefits of a healthy

population.

"To make money, you need good productivity, and if the workers are

feeling good, you get it," said 30-year-old Jun Masui, chief of auto-emission

controls. "So, it is cost-effective to clean up the air."

Japan's problems are far from over. I glanced out the window and noted

that buildings were disappearing behind smog. Nitrogen oxide emissions

from Tokyo traffic are still high.

Reduction of industrial emissions has been more dramatic. In Kawasaki,

the industrial hub, sulfur dioxide has been reduced 96 percent by installing

scrubbers and switching fuels. A central monitoring system tattles on plants

exceeding pollution limits, but such high-tech sentinels are costly. Each

of 18 stations measuring ambient air costs half a million dollars, more

than most countries are willing to pay.

LESS THAN a decade ago Mexico City was sliding toward prosperity on

an oil-lubricated national income. But long before the 1985 earthquake

devastated hundreds of its buildings, the collapse of world oil markets

had left its economy in a shambles. The hard-pressed government could not

afford to clean up air extravagantly dirtied. Raw sewage dries and is wafted

aloft to mix with heavy concentrations of fossil fuel emissions. Even so,

air over Mexico City takes a backseat to what may be the most polluted

corner on earth -- Brazil's "valley of death."

An hour's drive south of São Paulo the land drops away suddenly

to a coastal plain more than 2,000 feet below. Between the plateau and

the sea less than 15 miles away, industrial plants belch thousands of tons

of pollutants a day, some of them extremely toxic, some as common as dust

from a cement factory. Sharing the valley with the industries are about

100,000 people in the municipality called Cubatão.

Normally our respiratory systems defend against solid particles like

dust with filters of mucus and hair, but smaller specks from combustion

and manufacturing invade bronchial tubes. Inflamed, the tubes narrow, restricting

breathing. Within an hour of my arrival a dull ache nagged in my chest.

In the downtown core population of some 40,000, nearly 13,000 cases

of respiratory disease were reported in one recent year. Other health statistics

about Cubatão are more frightening. The air holds high levels of

benzene, a known carcinogen. One in ten workers in a Cubatão factory

unit showed low white-blood-cell counts, perhaps a precursor of leukemia.

Infant mortality is 10 percent higher here than in São Paulo state

as a whole. Environmental officials blame it on poor sanitation and malnutrition.

Surprisingly, I could find few who would complain about the pollution,

including those who live in its heart, a ragged cinder-block and sheet-metal

neighborhood known as Vila Parisi. Villagers there breathe fumes but smell

jobs. They are wary of industry offers for their property and government

offers of free homesites on a landfill.

"The refinery wants our land for expansion, and they offered us 500,000

cruzeiros [then $200] for it," said a young woman with an infant dabbling

in mud at her feet and another perched on her hip.

"Yes, the children are often ill and sometimes can barely breathe.

We want to live in another place, but we cannot afford to."

Dr. Oswaldo Campos, a university professor of public health, says the

dirty air in Cubatão is a case of economic priorities, not deliberate

callousness. "Some say it is the price of progress, but is it?" he commented

in a São Paulo coffee shop. "Look who pays the price-the poor."

Alesser price for all is hinted in recent São Paulo state statistics

on Cubatão's air:

In a two-year period, particulates down by 80 percent and varying reductions

in other pollutants. The remedial program is showing results, but there

is far to go.

next page