![]() Vale of tears Barry Bearak

Vale of tears Barry Bearak

![]() Waging peace in Kashmir Ved Bhasin

Waging peace in Kashmir Ved Bhasin

![]() Kashmir - Dandgerous discourd Oxford Analytica

Kashmir - Dandgerous discourd Oxford Analytica

![]() For 3K Freedom William Safire

For 3K Freedom William Safire

![]() Ask the Kashmiris what they want Viola Herms-Drath

Ask the Kashmiris what they want Viola Herms-Drath

![]() From the Indian Express: Swati Chaturvedi

From the Indian Express: Swati Chaturvedi

![]() Paradise lost under the threat of war: David Graves

Paradise lost under the threat of war: David Graves

![]() Indian democracy tastes bitter in Kashmir: Simon Cameron-Moore

Indian democracy tastes bitter in Kashmir: Simon Cameron-Moore

![]() Article 370: Victim of deceitful conduct: A G Noorani

Article 370: Victim of deceitful conduct: A G Noorani

EXTERNAL LINK

KASHMIR IS BLEEDING Surinder OberoiVALE OF TEARS: A special report

Kashmir a Crushed Jewel Caught in a Vise of Hatred

By BARRY BEARAK

SRINAGAR, Kashmir -- Sadly, alarmingly, endlessly, there is trouble in paradise. The Vale of Kashmir, once exalted for the lotus blooms in its lakes and the yellow tapestry of its mustard fields, has become a valley of despair -- a place haunted by senseless murder and hideous torture, wherever the famously sweet winds blow. For a half century, India and Pakistan have fought over this land, sustaining a hatred so venomous as to rival any in the world. For each, possessing Kashmir is a matter of life and death, with both persistently willing to forsake the former for the latter.

A macabre carnival of killing has come to mock a once-storied serenity as India suppresses a Pakistani-supported insurgency: people blown apart, ambushed, caught in a crossfire, snatched and disappeared. During the past decade, 24,000 have died by the Indian Government's official count. Others say 40,000 is a better estimate. Others, 70,000.

Here in Srinagar, the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir's summer capital, life has assumed a quality of war-weary numbness and morbid fatalism. "If only we could turn back the clock," said Irfan Maqsood, a 21-year-old student, in a typical lament. "The fighting goes on and on, and for what? We belong to India, and India will never let us go."

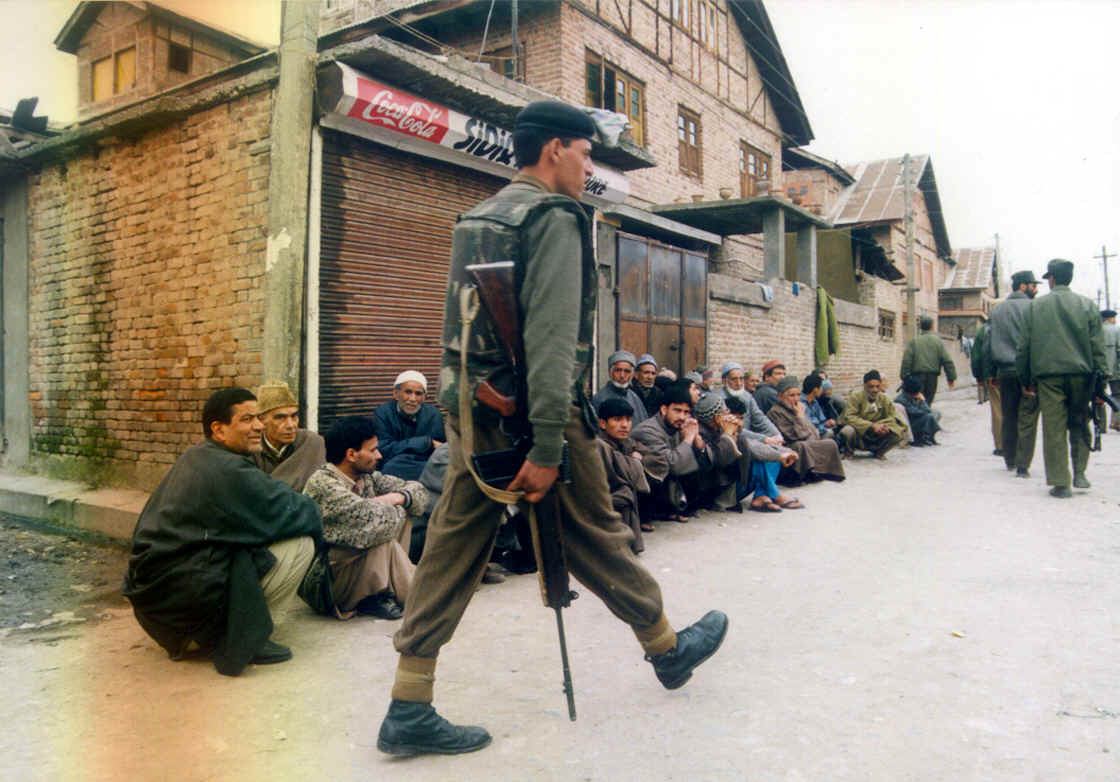

People have grown used to the street's stern accouterments. Heavily armed soldiers or policemen are always within sight. Bunkers are maintained every few blocks, their sandbags covered with blue tarpaulin, rifle barrels peeping out of rectangular slits. The police conduct dozens of "cordon and search" operations each day, surrounding a small area and then entering homes and shops, rousting out the men and taking away suspects.

Kashmir is caught in one of the world's violent loops, death begetting death. A grenade is flung into the courtyard of a police station. An hour later, in a crowded, airless hospital ward, Mohammad Yusuf Mir, a wounded policeman strung to an IV, is coupling his moans with an oath: "Whoever did this, I hate them. I curse them. I'll kill them."

The rebellion itself began 10 years ago. Weapons flooded in, tourists scurried out. At first, the insurgency was homegrown. Kashmiri youth, shouting azadi, or freedom, became guerrillas, trying to send India packing with a few well-placed bombs and high-profile kidnappings. Shopkeepers gave them cash. Mothers made them sandwiches.

To New Delhi, this was a threat to its nationhood, to Islamabad an opportunity to wage war by proxy. India has since tried to stamp out the revolt with all the fury of an enraged elephant, while Pakistan has tried to provoke the uprising further and arm it and bend it to its will.

Today, what is left in the valley is a populace stunned with confusion and sorrow, unwilling to give up the dream of independence and yet unprepared to endure more killing. People feel betwixt and between, their fate out of their hands. A common complaint is that India and Pakistan seem pitted against each other in a fight to the death of the last Kashmiri.

"We want to stand up and say to them both, 'Thank you for loving us, but spare us the honor of being your battleground,' " said Muzafar Baig, a prominent lawyer. Life seems forever transformed. A valley whose culture was once identified with the gentle teachings of Sufi mystics is now overwhelmed by the culture of the gun and the morality of the mercenary. Insurgency and counterinsurgency have bled into one another. Kashmir has become a place of double-crosses and extortion and vaporous truths.

Some days back, "Papa Kishtwari," a man with hard eyes and strong opinions, sat in his house sipping tea as a dozen or so supplicants waited outside to tell him their troubles. His real name is Ghulam Hassan Lone and he is one of the leaders of the so-called "friendlies," onetime insurgents who surrendered and then switched sides, becoming India's eyes and ears against the insurgents and sometimes its fists.

He recalled his days as an anti-India militant. According to him, Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency gave him money, guns and marching orders. "They told us what positions to hit," he said. "They gave us a list of people to be shot dead." Then he changed allegiance. The money was still good, the work similar, he said. He would identify militants for the Indian security forces. "There is a policy of extra-judicial killings," he said, something India denies. "This is done to impress New Delhi." But the days of the "friendlies" appear to be over. India has changed tactics and relies more on its own intelligence units to ferret out militants. "Pakistan used us, then India used us," Papa Kishtwari said bitterly. "This is what they do in Kashmir -- use us."

The History:

Since '47, a Puzzle Without a Solution Kashmir is one of the world's most confounding morasses, a 52-year-old custody battle where the contesting parties disagree on the details of every scrap of their common history.The very term Kashmir is ambiguous. Most often, it is used as shorthand for the entire Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, which has about eight million people. But the state has several distinct regions, of which the fabled valley, with slightly more than half of the population, is but one. Only there do people speak Kashmiri -- and only there do people have a distinct feeling of being a separate nation. Jammu is roughly two-thirds Hindu, though there are districts with a large Muslim majority. Sparsely populated Ladakh is half Buddhist and half Muslim. Once a princely state ruled by a maharajah, Jammu and Kashmir had even broader boundaries, including territory now claimed by Pakistan and China.

In 1947, the year that India and Pakistan were born, the departing British colonial masters demanded that the subcontinent's 562 landed maharajahs opt to belong to one infant nation or the other. Hari Singh, the state's Hindu maharajah, dithered past the deadline, but then, as tribesmen from Pakistan's northern frontier aided a local rebellion, he decided to cast the lot of his predominantly Muslim domain with predominantly Hindu India. To many Muslims, it seemed the land had fallen under the thumb of the infidel. War broke out between India and Pakistan, and an ensuing cease-fire left about one-third of the densely populated part of the state with Pakistan, where it remains today.

Jammu and Kashmir, while never happily a part of India, nevertheless lived in relative peace until the rebellion. Statewide, between Jan. 1, 1990, and July 15, 1999, the state police recorded 7,922 attacks with explosives, 9,393 random firings, 12,460 "cross firings," 3,553 abductions, 619 rocket attacks. The years 1993 through 1996 were the worst. During the past few years, the mayhem had actually moderated. Death tolls were nearly halved, curfews in Srinagar were lifted. Indeed, this spring some 100,000 tourists -- mostly Indians -- visited Kashmir. Dal Lake was again busy with colorful boats, the oarsmen gently paddling while visitors delighted in the graceful swoop of a kingfisher. But then in late May came "Kargil," the convenient term given to 10 weeks of fighting along snow-capped peaks in Kashmir. Pakistani-supported militants - New Delhi contends they were mostly Pakistani soldiers -- sneaked into India and seized the high ground above a vital supply route. India responded with air power and a vast deployment, with both sides finally braking at the brink of what would have been their fourth all-out war.

As the Kargil battleground, named for a town in central Kashmir, calmed down, hit-and-run tactics picked up throughout the entire state. More than 1,000 militants have recently crossed into Kashmir, making a total force of about 3,500 insurgents, Indian officials say. "The new ones are better armed and better-trained than we're used to," said Gurbachan Jagat, the state police chief. "They're professionals, with good radios and heavy explosives."

The character of the insurgency has been steadily changing.According to Indian military observers, about 40 percent of the militants are now foreigners -- mostly Pakistanis but also Afghans. They belong to various groups -- with varying political and religious beliefs -- but a few of the most powerful, like Lashkar-e-Taiba, are Islamic fundamentalists who have come to Kashmir on a holy war. While the Vale of Kashmir is overwhelmingly Muslim, a less dogmatic version of the faith is commonly practiced here, and Kashmiri nationalism has never been equated with religion. To some then, it seems the fight for independence has taken odd turns and attracted strange confederates.

Yasin Malik, a chain-smoking, gangling 33-year-old, is head of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, the most important group among the rebels. Since 1994, it has abided by a self-proclaimed cease-fire, but it does not condemn anti-India violence by others, anything to keep the pot stirring. Still, Malik has regrets: "It is too bad that when Lashkar-e-Taiba speaks, people believe this is the voice of the Kashmiri people." The active guerrilla groups are not united in any single military strategy, though they now often avoid the concentration of Indian security forces in the valley and operate in the thick forests and isolated villages of Jammu. One tactic is to massacre Hindu innocents, hoping to set off communal violence. Another is political assassination. Another involves bold rocket attacks against army installations. New Delhi continues to use a heavy club to fight back, something that has repeatedly drawn condemnations from international human rights groups. From the Indian Government's vantage point, however, the nation deserves to be commended for restraint. "We've kept our response low-key and measured," said Gov. Girish Saxena, New Delhi's man in Srinagar. "We did not use tanks and armed personnel carriers. We have generally confined our response to small arms, and that has made an impression on people that we are trying to deal with the situation in a civilized way."

India maintains about 200,000 regular army troops in Kashmir, most of them warily guarding against a Pakistani attack. Fighting the guerrillas is now largely left to 125,000 others from paramilitary units and the state police, Governor Saxena said. Additionally, the state has armed 18,000 villagers - costly Hindus in Jammu -- to defend themselves. They call them village defense committees.That is a lot of firepower -- and the reproach of rights groups continues. Indeed, it is not difficult to locate men with convincing tales of recent torture, ugly engravings on their skin, a palette of black and blue on their limbs. Parents wait by the gates of army camps and police stations, holding photos of sons who have been taken into custody and never seen again.Bystanders are too often mistaken for perpetrators, said Raja Banoo, whose 16-year-old son has been gone for 28 months. "Before the army took him, they beat him right in front of me and dug a hole and said, 'We'll bury your son alive,' " she said.The state government opened its own human rights commission in August 1997, but it is widely regarded as toothless.

By and large, the state police have been entrusted to look into rights abuses. Their records show a total of 3,197 complaints, including allegations of 1,105 "custodial deaths," 1,248 "innocent killings" and 512 "disappearances."

Of these cases, barely 3 to 4 percent seem to "merit any follow-up," said R. Tikoo, the assistant director general of the central intelligence division.The rest, he said confidently, are exaggerations or outright lies.

The Future:

Could Clinton Act as Peacemaker? A common sentiment heard in Kashmir comes out as a question: Why isn't the world paying more attention? And if there is a silver lining to the Kargil episode, it is that for a time the world did -- and may still. With India and Pakistan now nuclear powers, hostilities between them have apocalyptic potential. A turning point in the crisis came after Pakistan's Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, met with President Clinton in Washington on July 4. This may be grasping at straws, but many here are putting considerable hope in a two-word pledge issued after the Clinton-Sharif meeting. The President agreed to take a "personal interest" in urging the resumption of Indian-Pakistani peace talks. How personally he will be involved, and how interested he truly is, is uncertain. America's position remains that Kashmir is a disputed territory, and a solution is best left to bilateral talks between the two nations. That would be fine with India, which considers Kashmir to be an open-and-shut case and officially refuses to acknowledge that a dispute even exists. Still, Kashmiris are encouraged. Shahid-ul-Islam, a former guerrilla commander from the group Hezbollah Mujahedeen, said: "We take a positive sign from Kosovo. We had thought Clinton was anti-Muslim, but now we believe he may be an angel for peace."

Prof. Abdul Ghani Bhat, head of the Muslim Conference political party, said: "The President of America wants to go down in the annals of history as a peacemaker. That is why he said 'personal interest.' He will force India to negotiate." President Clinton hopes to visit the subcontinent early next year -- and certainly the issue of Kashmir will come up. It has poisoned the relations between two poor countries with a combined population of 1.1 billion -- nearly a fifth of all humanity. But if the President forcefully enters the Kashmir fray, he will find himself wandering within that 52-year-old morass, which has so defiantly resisted solutions. Twice, back in 1948 and 1949, India committed itself to a United Nations-sponsored plebiscite, allowing the state's people to decide whether to be part of it or Pakistan. This vote, however, was made to be contingent on a pullback of armed forces by both sides, an exercise requiring trust. The vote has yet to occur.

"That referendum must be held and we would abide by the decision, but the choices must include independence," said Malik of the Liberation Front. But the results of any statewide vote -- even one with three choices -- is likely to leave as many people dissatisfied as there are now. Ladakh and parts of Jammu would want to stay with India, parts of Jammu would prefer Pakistan. To deal with that prospect, a half century of thinking has yielded any number of options, including joint sovereignty arrangements and ways of dividing up the state between India and Pakistan and allowing the valley to become independent. Regional plebiscites, instead of a statewide one, is another suggestion frequently made. But nothing will happen unless all parties are willing to negotiate and compromise. "President Clinton could get everyone to talk, don't you think?" said Abdul Majid Wani, a retired engineer who was walking in a cemetery called Martyr's Graveyard. His son is buried there. Ashfaq Majeed Wani, one of the first young men to

take up arms against India, was killed on March 30, 1990. He was 23, and when his father identified the body, he counted 21 bullet holes. Ashfaq was also missing several fingers, and the elder Wani proudly speculated that his son died with a grenade in hand. There are more than 1,000 simple graves in the cemetery, which is beside a soccer field. Wani conducted a brief tour, pausing at one marker or another to describe more death. At the end of one row rested a 4-year-old, Master Shaheed Yawar, killed in a crossfire. Wani did not want the poetics on a nearby sign to be missed.

It said: "Do not shun the gun, my dear younger ones. The war for freedom is yet to be won."

Courtesy: New York Times - August 12, 1999

Waging peace in Kashmir

Ved Bhasin

Of the three wars in the Sub-continent between the neighbouring states of India and Pakistan two were fought in while or in part over the control of the territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The third, though primarily related to the liberation of Bangladesh from Pakistan due to popular revolt in erstwhile East Pakistan, soon engulfed Jammu and Kashmir. The Kashmir dispute which has bedeviled relations between India and Pakistan for over half a century has undoubtedly been both a cause and consequence of their perpetual enmity. The possibility of the ongoing struggle in Indian side of Kashmir for nearly a decade now, with Pakistan helping and assisting the insurgent groups for its own territorial designs, and which does not see any signs of subsiding despite the strong arm methods used by the Indian state soon escalating into a fourth and bloodiest war cannot be discounted. With both India and Pakistan, in their race for improving their respective war machinery, emerging as the nuclear powers with the latest nuclear tests, Jammu and Kashmir has become a nuclear flash point. The consequences of any such war can be easily imagined.

Clearly, Jammu and Kashmir problem has been both the cause and consequence of unending Indo-Pak conflict. The genesis of the unresolved Kashmir problem is as complex as it is disputed in view of the divergent perceptions of relevant history - political, legal and constitutional. One need not go into the past as any such exercise could only ignite passions, sharpen polemics and prove counter-productive. Nonetheless the dispute is the consequence of the sub-continent's partition and vagueness about the fate of the people in the princely states who were left to the mercy of the erstwhile rulers. It was the vacillation and indecision of Maharaja Hari Singh in deciding on whether to join India or Pakistan or remain independent after the transfer of power the created the problem. After the transfer of power the British paramouncy lapsed and legally and constitutionally Jammu and Kashmir became a fully sovereign independent state. It remained so till October 27, 1947 when the ruler signed the Instrument of Accession with India under peculiar circumstances. There is little doubt that the Maharaja nursed the ambition of proclaiming himself the emperor of a sovereign autocratic state and his supporters and loyalists did rejoice on August 14-15 when the two independent dominions came into being for Jammu and Kashmir "becoming a sovereign independent under Maharaja Hari Singh". It is also not beyond dispute that for altogether different reasons Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the then largest political party of the State, wanted Jammu and Kashmir to emerge as an independent state with sovereignty vesting in the people and not the ruler and power transferred to his party. It was the mutual animosity of the two that stood in their way of fulfilling their respective ambitions. With the state depending on both the dominions, the Maharaja for having breathing space, offered standstill agreements to both, which was turned down by India but accepted by Pakistan. The former to pressurise the ruler to join the India Union and the latter with the hope that he will surrender before the newly created state of Pakistan sooner than later. Pakistani leaders considered the Muslim majority state of Jammu and Kashmir as its natural part, based on its two nation theory. While the Maharaja vacillated under divergent pulls and pressures and under different influences, it was Pakistan which in its haste to grab Jammu and Kashmir armed and sent tribal and irregulars into the State. The revolt by a section of the people in the border areas of Mirpur and Poonch and frontier areas provided a God-send opportunity to Pakistan to achieve its territorial designs. The rest is history. It was to save his State from the raiders, who resorted to loot, plunder and killings, that the Maharaja was left with no option but to sign the Instrument of Accession with India when the later made it conditional for sending the troops to face the challenge from Pakistan. The document was accepted by the then Governor General of India Lord Louis Mountbatten, with the provisio that the ultimate fate of the state will be decided by its people. The Maharaja also made it clear that the Instrument of Accession was limited to Defence, Communications and Foreign Affairs and that in other subjects the sovereignty rested with him. This made the accession both limited and conditional. Perceptions differ about the limited and conditional nature of the accession. Both India and Pakistan agreed to these conditions prior to the United Nations establishment of a cease-fire effective from January 1, 1948.

The legal and constitutional position apart, Jawahar Lal Nehru as the Prime Minister of India reiterated time and again till 1954 that the future of Jammu and Kashmir would be decided by the people through a plebiscite and till the final decision the State will enjoy full autonomy except in the matters of three subjects which it ceded to the centre. The UN resolutions of 1948 and 1949 remained unimplemented for years for a variety of reasons about which the perceptions differ. Going into those reasons and pin pointing blame will not serve any useful purpose. The subsequent efforts to resolve the crisis through bilateral talks and even with the good offices of outside powers proved abortive due to the rigid posture adopted by both the countries who ignored the basic premise that the will of the people of Jammu and Kashmir should prevail in such matters. Whether in the Tashkent Declaration or subsequent Simla talks no fruitful result could be achieved, mainly because it was considered as a territorial dispute between the two countries, ignoring the principal party in the dispute, i.e. the people of Jammu and Kashmir. The Simla agreement of 1972 too considered the Jammu and Kashmir problem as a question of dispute between India and Pakistan, The people of Jammu and Kashmir were not taken into account. Nonetheless the agreement did refer to the "final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir". While committing both the countries "to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations or by any other peaceful means mutually agreed upon by them." It envisaged further discussions "for the establishment of peace and normalisation of relations including ..... a final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir."

No further discussions were held on the final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir. During subsequent dialogue between the two countries to resolve their difference India asserted that the future of Kashmir was not negotiable while Pakistan described it as a crore issue. The issue concerns the people of Jammu and Kashmir and the two countries come into the picture only because it is both the cause and consequence of Indo-Pak conflict. Primarily it is people of Jammu and Kashmir who have to decide about its future and final settlement. The perceptions about the legality or temporary nature of the Instrument of Accession signed by the Maharaja on October 27, 1947 too differ. No useful purpose can be served by going into this aspect: Similarly the question whether the conditions laid down by the Maharaja and accepted by Lord Mountbattan for setting the "question of State's accession by reference to the people" is interpreted differently by different parties and persons. The same is true about the limited nature of the accession which made it abundantly clear that the accession was limited to the three subjects of defence, foreign affairs and communications and in other matters the state enjoyed full autonomy and as the Maharaja in his letter forwarding the Instrument after appending his signature put it "the sovereignty" rested in him (the people of Jammu and Kashmir).

The commitment of India, as made by Jawahar Lal Nehru publicly, and its representatives in the United Nations that as soon as the peace returns to Jammu and Kashmir plebiscite would be held to finally determine the future of J&K may have no legl or constitutional binding but this is a moral commitment which cannot altogether be ignored. The United Nations Security Council too suggested the holding of plebiscite with certain conditions. Both India and Pakistan accepted it. That Pakistan did not fulfill those conditions and that situation changed since then too does not absolve India of the commitment. For this commitment was not made to the UN or Pakistan but to the people of Kashmir and if the UN did not pursue it or Pakistan did not fulfill the conditions including vacation of the areas occupied by it and removal of its forces with handing over those areas to "the lawful government of Jammu and Kashmir" it is no fault of the people of Jammu and Kashmir and they cannot be deprived of their basic right of self-determination on that ground. Interpretation of Article 1 of the Constitution of India which mentions the territory of the country and includes Jammu and Kashmir too differ. While Article 1 applies to the other territories of India by its own force in relation to the State of J&K it applies only through Article 370. Clause (1) (c) of Article 370 says: "the provisions of Article 1 and of this Article shall apply in relation to the state. This Article has been mentioned as transitional and provisional. But once Article 370 is deleted, the application of Article 1 in relation to J&K shall automatically cease to operate".

"The various provisions of constitution of India are to be read harmoniously and not in conflict with one another. So the provisions of Article 1 are to be read in conjuctively with Article 370 and Article 1 is not to be read in isolation in respect of State of Jammu and Kashmir, but subjected to provision of Article 370". It is clear that if Article 370 is deleted Article 1 in relation to J&K as the territory of India also ceases to operate. This also amply shows that the farmers of the Constitution too accepted the provisional nature of the State's accession to be ratified for this purpose.

Sheikh Abdullah referred to this aspect when referring to the proclamation for electing a constituent assembly for the state in May 1951, he described it as " the day of destiny" and called the consembly as a "sovereign authority". He listed the main objects and functions of the Constituent Assembly as follows:-

i) to frame a Constitution for further governance of the country (meaning Jammu and Kashmir)

ii) to decide about the future of the royal dynasty;

iii) to decide whether compensation should be paid to the land owners for the expropriation of the Big Landed Estates, carried out in pursuance of the Land Abolition Act (Act XVII of S 2007);

iv) to declare its reasoned conclusions regarding accession and the future of the State.

Sheikh Abdullah enumerated three alternatives for the future of J&K: accession of India; accession to Pakistan or complete independence. That show the temporary nature of the accession and a truly democratic elected constituent assembly could have taken a decision on it to bury the question for ever. But that was not to be and the entire exercise of the framing of the Constitution whose clause 1 described the state as an integral part of India and could not be amended cannot be accepted as valid for various reasons. First, the election to the assembly held under Sheikh Abdullah's leadership was totally rigged with 73 out of 75 members having been rigged and varying degrees. Secondly, the validity of the Constituent Assembly was further eroded with the undemocratic deposition and arrest of Sheikh Abdullah in August 1953 and it totally lacked representative character. It did not reflect the will of the people.

The subsequent rigging of elections to the assembly to implant pliant governments, denial of fundamental and democratic rights to the people through the enforcement of draconian laws, large scale arrests of those representing dissent and consistent and planned erosion of the autonomy granted to the state in surreptitious manner further damaged India's image in Jammu and Kashmir. This along with the mis-governance, large-scale corruption, arbitrariness and ruthlessness, growing unemployment and deteriorating law and order situation due to the acts of omission of commission of the successive state governments resulted in total alienation of the people. With all democratic channels closed on the people the unrest turned out to be violent with dissatisfied youth taking to guns. The people of India, unfortunately have been fed with lies by the rulers in New Delhi, about the actual situation in Jammu and Kashmir. What happened in the State since 1990 need not be enumerated. The trouble in Jammu and Kashmir cannot be dismissed as inspired by ISI or proxy war by Pakistan. There is no doubt that Pakistan exploited the situation to its advantage and fulfil its nefarious designs to grab Kashmir, But primarily it was the popular revolt by a large section of the people which was widespread in the valley. No less a person than George Fernandes, presently Defence Minister of India, who was the minister incharge Kashmir Affairs in Janta Dal government in 1990 said: "I do not believe any foreign hand created the Kashmir problem. The problem was created by us.... others decided to take advantage of it". (India's policies in Kashmir: An assessment and Discourse: Raju Thomas page 286).

Whatever his present views, even Dr Farooq Abdullah admitted in 1994: "It is India that is responsible for what has happened in Kashmir....(India Today: 1994: Page 44). The former Chief Minister Mir Qasim put it more succinctly: "If I dump petrol in my house.... and my opponents set a match to it, it is largely my fault... whatever the entire people rise up in once voice, you cannot suppress it by force..."(Life and Time 1992: Page 302-3).

What is the Solution

Clearly the policy of suppression pursued in Jammu and Kashmir since 1990 has not succeeded to eliminate militancy, much less to crush popular unrest or bring back the people to the national mainstream. The bullet for bullet policy with untold human rights violations has proved counter-proved counter-productive. It has not only added to the people's unrest but has also besmeared India's fair name world over. Such a policy has its own limitations even if the militants, with Pakistani support, cannot match with the armed strength of the Indian state. Even if the militancy is crushed it is bound to reappear in one shape or the other. Peace will not return to Jammu and Kashmir.

For the militancy is the consequence and not the cause of popular unrest and people's alienation. Unless the root cause of militancy and the people's disenchantment with India is tackled no worth while and lasting solution is possible. Primarily it is a politi cal problem which cannot be tackled with armed strength by deal ing with it as simply a law and order problem. It calls for a political solution. A political solution that could satisfy the urges and aspirations of the people of Jammu and Kashmir living in all regions and areas and belonging to all faiths and communi ties, that could also be eventually acceptable to India and Pakistan is called for.

Various suggestions and alternative solutions have been suggested. There can obviously be no solution on the basis of status quo. The suggestion which Dr Farooq Abdullah has been making for accepting the present line of control as the permanent boundary between the two countries suffers from various drawbacks. It is based on erroneous premise that J&K problem is only a dispute between India and Pakistan and that it is a territorial problem. J&K is not a just of piece of land that it should be divided between India and Pakistan, It is the people who constitute Jammu and Kashmir. The solution is obviously not acceptable to Pakistan which is already, though unlawfully, holding the area beyond line of control. The present unrest is mostly in this part of Jammu and Kashmir and Farooq's solution does not take into account the aspirations of the people and would in no way satisfy them. Any solutions based on status-quo, geographically and politically and constitutionally, cannot be considered rational and realistic and will not in any case be acceptable to the people who have risen in revolt.

The militants and their political supporters have been taking of Azadi, reiterating the people's right of self- determination. The right cannot be disputed but one has to give a thought to the complexities in this regard. Jammu and Kashmir is a multilingual, multi-religious, multi-ethnic state and not a homogenous entity. It is the creation of conquest, annexation etc by the erstwhile Dogra rulers. There are divergent perceptions and aspirations of the people living in different regions and areas. What is to be the unit of self-determination in such a pluralist society? The exercise of the right in a state which exhibits multiplicity of ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious differences can only lead to its fragmentation with all its dangerous consequences. If the people are the final arbiter and have to decide their future then the question who constitute people has to be tackled before any solution is found. The divergent aspirations ranging from total integration to Azadi (with partition and status quo in between) have to be reconciled. This calls for a meaningful dialogue between all sections of the people without any pre-condition. The slogans like 'atoot ang" and ""Kashmir banega Pakistan" will have to be discarded. The claims of Kashmir being crown of India or a lifeline and natural part of Pakistan too flow from wrong presumption of it being only a question of territory.

The dialogue without any preconceived notions and without any conditions is imperative to arrive at a solution that could be just, fair, realistic, rational and practical. Such a dialogue should be at various levels and in different phases. Between the people of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh on this part of the State, between India the people of this part and those in "Azad Kashmir" and finally between India and Pakistan which are supposed to endorse the consensus arrived at by the dialogue between the people of Jammu and Kashmir. For such a dialogue the necessary climate needs to be created by adopting confidence building measures in this part of the state. For this purpose peace should return and the element of fear eliminate so that every section can express its open without any fear. The first step is for ceasing the hostilities and effecting a kind of cease-fire between the gun wielding militants and the security forces. The forces must be removed to barracks from all civilian areas and bunkers removed and a minimum force should be kept in the state. Pakistan must desist from arming and assisting the militants and prevent them from crossing the line of control. Both India and Pakistan must disengage themselves in Siachen where the forces of two countries are unnecessarily facing an eye ball situation with huge loss to their respective exchequers and more in terms of the blood of their soldiers. At the same the two countries should withdraw the bulk of their forces from both sides of the line of control and the incidents of exchange of fire should be checked through proper monitoring the supervision. All prisoners should be released and draconian laws made inoperative if not altogether removed from the statute. The civil liberties should be restored by allowing holding a peaceful public meetings and processions. Steps should be taken for the return and proper rehabilitation of all migrants and creating a sense of security among them. All arms by the militants, ex-militants or the village defence committees should be surrendered to remove the fear of gun.

These measures should be followed by creating necessary conditions for all sections including militants to join the dialogue at the place of their choice. The leaders of this side should be permitted to visit the other side for exchange of views and evolving a realistic solution of the problem. To my mind independence for Jammu and Kashmir as a sovereign independent, federal, democratic and secular state with autonomy to all its regions by creating regional assemblies and government and center having only limited power and safeguards for ethnic and religious minorities fully guaranteed could have been an ideal, realistic and just solution of the problem. In that case J&K would have become a bridge rather than a cause for conflict between India and Pakistan. But at present such a solution does not appear practical in view of Jammu and Kashmir having become an emotive issue for the people both in India and Pakistan, political compulsions of the ruling elite in the two countries and opposition from within with a section in Jammu even demanding abrogation of Article 370. A traditional solution which could satisfy all the conditions enumerated above is possible and worth discussion among different sections of the people during their proposed dialogue. This can be a transitional solution to be later ratified or amended by the elected representatives of both sides after, say, ten years. Let this side of Jammu and Kashmir enjoy total autonomy within Indian Union as envisaged in the Instrument of Accession signed in October 1947 with New Delhi having only defence, foreign affairs and communications and the state enjoying sovereignty in all other matters. Similarly autonomy should be given within the state to all the distinct regions and areas, carrying this to the grass root level. Pakistan should ensure same quantum of autonomy to the areas under its control. The defense of areas under their control should be the responsibility of the respective countries.

The author is former Editor of The Kashmir Times, Jammu

OPINION- Kashmir - Dangerous Discord

Jun 11, 1999 By Oxford Analytica

OXFORD, England, June 11 - Indian military forces are currently seeking to remove a group of 600-800 Islamic guerrillas based in Kargil, on the Indian side of the border separating India from Pakistani-held Kashmir. The conflict has heightened tensions between Delhi and Islamabad -- both new nuclear powers -- and drawn the attention of the international community to the status of Kashmir, which has long been disputed between them. While neither side may wish to escalate the conflict, it is uncertain how far either country is in control of military activities on the ground.

Moreover, neither country appears sufficiently stable politically to restrain events. The status of Kashmir has been hotly disputed between India and Pakistan since the creation of both states during the 1947 partition. They have subsequently fought two wars over the province and developed the most precarious of truces within it. An internal insurrection in 1989 against Indian rule has made this fragile peace all the more difficult to maintain. Every spring, guerrilla activities commence on the Indian side of the Kashmir ``line of control'' and sporadic cross-border firing between the two sets of military posts resumes. Events this spring have taken a somewhat different turn. Under the cover of snow, a substantial group of Islamic guerrillas (believed to be Afghan Talibaan) moved into the remote Kargil area, and laid claim to the ``liberation'' of 193 square kilometres of ``Indian'' Kashmir. If allowed to remain on the land, they would effectively shift forward the frontier of Pakistan's ``Azad'' (Free) Kashmir. In consequence, Indian forces have launched a large-scale effort devoted to driving out the guerillas; they have even resorted to aerial warfare not seen in Kashmir since the last full-scale military conflict with Pakistan. However, the terrain is difficult to navigate and, thus far, the guerrilla encampments remain in place. Moreover, Pakistan is mounting a vigilant defence of its own borders and has shot down several Indian Air Force jets which strayed into its airspace.

There is a serious danger that the conflict could escalate. To some degree, the conflict is already intensifying, with cross-border fire now taking place regularly along the Kashmir line of control. However, neither Delhi or Islamabad wants to push the issue to outright war. The Lahore Declaration, which offers a new period of amity between the two countries, was only recently signed by Indian Prime Minister Atul Behari Vajpayee and his Pakistani counterpart Nawaz Sharif. Similarly, Pakistan's real strategic aim -- which is to bring international arbitration to bear on the Kashmir question -- would not be well be served if Islamabad were seen as the aggressor in the dispute. Indeed, Sharif has claimed no prior knowledge of, and no military support for, the original incursion force. Sharif and Vajpayee may not be fully in control of events and face domestic pressures to assume aggressive postures. In Pakistan, three issues complicate the question:

- Sharif is attempting to consolidate his personal power in the face of considerable opposition, particularly from the regions. He may believe that his position could be significantly bolstered if he spearheaded the drive to achieve a deeply felt national goal.

- Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency has long enjoyed considerable independence in strategic affairs, often adopting different positions from the government and other parts of the military. ISI personnel have been seen in proximity to the incursion force and the agency may be precipitating the conflict for its own ends.

- Sharif fears the influence of the Talibaan in Afghanistan and has already made many concessions to the movement. Rumours persist that an even larger Talibaan force (some 2,000-3,000 strong) are ready to cross the Kashmir border to launch a jihad. If this were the case, Sharif would be disinclined to stop them.

- Vajpayee also faces domestic difficulties. He heads both a Hindu nationalist party which is highly sensitive to security issues and an interim government awaiting a general election in September. He does not want to be perceived as a leader who might compromise the integrity of India's national frontiers. His government has already incurred considerable popular opprobrium for allowing the incursion to occur in the first place, apparently unnoticed until the spring snows melted. Two army commanders have been dismissed and the position of Defence Minister George Fernandes has become increasingly uncertain. A further complicating factor is that military and air operations in the Kargil area -- conducted across mountainous terrain and over ill-drawn frontiers -- are particularly likely to result in unforeseen ``incidents'' that might escalate the conflict. For instance, the recent shelling of a school which resulted in the deaths of 10 children raised popular calls for revenge. Nonetheless, forces arguing for restraint also exist. In India, the criticism that the government has faced for permitting the incursion is double-edged. The public is aware that the bombing and fighting is being conducted on Indian territory. It may serve the parties in the interim government better to play down, rather than adopt a belligerent stance, towards the present conflict. Adopting a moderate stance could also improve Delhi's standing in the international community.

Washington is eager to limit the confrontation in order to secure the signatures of India and Pakistan to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty by September. Delhi could gain important support for some of its wider international goals (such as a U.N. Security Council seat) if it adopts what the international community views as an intelligent position towards the conflict. Moreover, Delhi's own strategy in Kashmir depends on the issue not becoming ``internationalised'' -- which requires the goodwill of the United States and would almost inevitably happen if the present conflict becomes a war. Islamabad's strategic ambitions are diametrically opposed. It is seeking to ``internationalise'' the issue -- and may have been encouraged to intensify the pressure on India by recent events in Kosovo. Pakistan is heavily dependent economically on the United States and only recently avoided bankruptcy. Washington thus far has shown no signs of reneging on its long-held opposition to assuming a mediation role in Kashmir -- which would mean forcing Delhi to the negotiating table. Islamabad is unlikely to have the means to change this. Moreover, Pakistan's other principal foreign allies -- China and Saudi Arabia -- also have their own reasons for wishing to see the conflict contained. With Tibet in mind, Beijing would not want Kashmir to appear on any international agenda. Similarly, Saudi Arabia is aware that a war with India would jeopardise the domestic security of India's 120 million Muslim citizens.

Ultimately, both sides have much more to lose than to gain from permitting the conflict to escalate towards full-scale war. However, interest groups within each country appear to have ambitions of their own which could sustain confrontation. Military miscalculations on the ground could cause events to move in undesired directions.

(Oxford Analytica is an international consulting firm that provides analysis of worldwide political, economic and social developments. It also provides a segment in the Emerging Markets programme broadcast by Reuters Television at 1430 GMT each Thursday. The opinions expressed in this article represent the views of Oxford Analytica only. They should not be seen as reflecting the views of Reuters.)

ASK KASHMIRIS WHAT THEY WANT

Viola Herms-Drath

This week's US pressure on Pakistan to withdraw Pakistan-backed Islamic militants from Indian territory in divided Kashmir is a step forward, but contributes little to a lasting settlement of the Kashmir issue. It's apparent that guerrillas demanding independence for Kashmir are not simply "morally" backed by Islamabad, as Pakistan maintains, but are actually equipped by independent units of the Pakistani Army, as charged by India and echoed by the White House. It is a provocation to India. India's official return of the bodies of three Pakistani soldiers killed in fighting on the Indian side of the Line of Control (LoC) is an implicit reminder of Pakistan's prevaricating. Though accustomed to constant skirmishes along the LoC between India and Pakistani controlled territory in Kashmir, this confrontation takes on a profoundly different character when Islamabad begins to question the legality of that border line, agreed upon by the two sides in 1972.

The presence of Pakistani officers participating in attacks alongside the mercenaries in Indian territory is evidence the spirit of the Lahore Declaration has been forgotten. In that widely heralded initiative last February, both sides reiterated a commitment to continued confidence-building measures. But, current worrisome developments have further internationalized the Kashmir issue by prompting the G-8 for "restoration of the LoC" and removal of "armed intruders" from Indian Kashmir. In view of these efforts, the argument for breaking the military deadlock on a bilateral basis seems less convincing. Though India regards the religiously charged conflict over Kashmir's final status as a closed bilateral issue, many in Pakistan maintain it is unfinished business for international mediation.

While Pakistan denies controlling the Muslim insurgents fighting Indian troops, India refuses to conduct any kind of dialogue with Pakistan while any rebels remain on Indian territory. Surely after 50 years of turmoil causing the deaths of untold thousands of Kashmiris (Muslim and Hindu alike), the creation of hundreds of thousands of refugees, and the massing of Indian troops to guard the vast region, time has come to consider alternative political solutions. Having never fully understood the volatile dynamics among South Asian neighbors, the West's benign neglect may be reflected in the current outbreak of violence. Though the international community has voiced its concern over Pakistan's military adventurism into India, no state has taken the risk of offering potential long-term political solutions governing the future of Kashmir. The recent introduction of nuclear weapons into the region suddenly finds the US committed with the international community to ensuring a peaceful outcome in the current military standoff.

The international community should recognize that defusing today''s military crisis is only a part of the larger problem. A lasting Kashmir settlement is to be found somewhere amongst the political options - accession to India or Pakistan, independence, partition, or condominium - that inevitably require compromises. To contain the conflict, a weapons-free zone along the LoC, or full demilitarization are subjects that should be considered. But continuous civil uprisings in Kashmir signal loud and clear that the voice of the Kashmiris should no longer be ignored. These 7 million people have never been asked what they want. The international community could push for the peace process by coaxing both India and Pakistan into a bilateral settlement. The time has come to heal the Kashmir crisis before a massive collapse destabilizes the entire region. Leaving the problem unresolved risks strengthening the cause of independence within Kashmir - a prospect undesirable to both India and Pakistan.

• Viola Herms-Drath is the diplomatic correspondent of Germany's Handelsblatt newspaper. She is based in Washington, D.C.

Courtesy: Christian Science Monitor, Wednesday, July 7, 1999

For 3K Freedom

By WILLIAM SAFIREA cry for self-determination is again sending shudders through world capitals. This time it's in Kashmir, a lovely land coveted by autocratic Pakistan, most of it occupied by 600,000 troops of democratic India. Pakistan unofficially sent a small force across the "Line of Control" to take up mountain peak positions, and the Indian Army is fighting -- literally uphill -- to drive them back. The purpose of Pakistan's raid is to get world attention paid to India's unwillingness to negotiate the status of Kashmir, which both sides claim. At the moment the world sides with India because it is resisting an act of aggression, albeit symbolic.

What has everybody touchy is that India and Pakistan are now nuclear powers, and a third war between them could depopulate the subcontinent. Last week, Pakistan's Prime Minister felt the need to race to Washington to seek President Clinton's mediation. Why? My guess is that Chinese intelligence, which has penetrated India's nuclear facilities as much as it has our own, tipped off its longtime ally, Pakistan, about increased Indian nuclear readiness. China also wishes its ally to back off because world pressure on India to end its occupation of Kashmir would set a precedent for Tibet. As a result, Clinton promised to take a "personal interest" (which India wants no part of). Pakistan's Prime Minister raced home to tell his generals they had made their point -- and should now pull back those supposedly freelancing liberators. Let's climb up our own mountain peak to survey the international 3K trend toward "protectoration."

In Kosovo, NATO acted forcefully to stop Serbia's bloody assertion of sovereignty. Because we are loath to redraw borders, we deny Kosovo independence but will enforce its autonomy. It is now a protectorate of NATO; after a decent interval, a plebiscite will probably be held to permit self-determination. In the Kurdish section of Iraq, the U.S. and its allies have bolstered their "no-fly" edict with a "no-go" policy toward Saddam Hussein's tanks. The dictator knows that if he moves on Kurdish self-governing forces in his north, out will go the lights in Baghdad and sirens will sound in his germ warfare factories. Iraqi Kurdistan is a de facto protectorate, dependent on the resolve of the U.S. President.

In Kashmir, we see a protectorate-in-waiting. As the British learned in India, and as the Israelis learned on much of the West Bank, a democracy's administration of a hostile population is ultimately self-defeating. And India is a democracy. Much as it wants to incorporate Kashmir, it faces growing local resistance and its own ensuing repression and brutalization.

Forget "world opinion"; Indian self-respect and economic self-interest will impel it toward the granting of ever-greater autonomy to the Kashmiris. But what then? Autonomy is desirable; it is seen as a grand experiment in diversity-within-unity, and works fine in Puerto Rico and Scotland. But in most of the world, autonomy is a peaceful stop on the way to self-determination. In Kurdistan and Kosovo, that means independence. What about Kashmir? In India's eyes, Pakistan is a garrison state with connections to Afghan terrorists and with missile ties to Communist China and crazy North Korea. It salivates at the prospect of swallowing Kashmir. Would Kashmiris be able to fend off or be better off under militant Muslim rule? Moderate Pakistanis say: Give Kashmir much more autonomy. Start pulling out your occupation forces. We'll promise not to infiltrate. Let the Kashmiris decide their future. India won't go for that for years. But Kashmir is like a fault in the political earth, the tectonic plates under growing pressure, and the now-nuclear region has much to fear from the Big One. The answer may well take the form of protectorate as it has in Kosovo and Kurdistan -- but in this case, the intercession would be invited by all three parties rather than punitively imposed. Nobody planned this protectoration trend. Nor does it offer finality, because the world is not about to take over the world. But it seems to be a way of giving peoples time to sort things out for themselves.

Courtesy: New York Times,Friday July 9, 1999

Swati Chaturvedi in The Indian Express, New Delhi

"Aag lagao. Mere ko dead body chahiye". This is how J. K. Sharma Additional Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG), Commandant of Border Security Force's 75th battalion, is to have told his men before they shot nine innocent civilians in cold blood in Mashali Mohalla, Srinagar district, on August 6, 1990. Now the BSF court of inquiry is drawing to a close. This will be the first court martial of its kind and E N Rammohan, Director General of the BSF, says the final orders against the DIG and others, will be issued later this month.

"The BSF is ashamed of this incident," Rammohan told The Indian Express. "Innocent civilians were killed and there is no question of the perptrators of the crime being spared." Under BSF rules, allegations of misconduct are first dealt by an in-house Recording of Evidence (ROE) in which the accused are given an opportunity to present their case. Once the offence is established, a court of inquiry is ordered which may culminate in a court-martial. Besides DIG Sharma, the other BSF personnel accused are Deputy Commandant R P Bhukal; Head Constable Gajjan Singh and Constable Uttam Singh. All four were initially suspended from service and subsequently given "routine" postings.

The court of inquiry charged Sharma with " omission of effective command and control over his troops which led to uncontrolled firing which led to the death of civilians." The other charges are culpable homicide (not amounting to murder) and causing grievous injuries. Sharma has also been charged with committing an outrage on the modesty of a woman. The three BSF personnel also face similar charges. The maximum prison term they face under the Indian Penal Code is seven years. Evidence recorded by the BSF shows that the party led by Sharma let loose a nightmare on the residents of Mashali Mohalla at 8.50 PM on the fateful night. Houses were set on fire, ammunition and arms were "planted" in the homes of the victims and one women, who had minutes ago seen her husband being shot down by the BSF Jawans, molested. Two other women, living in houses nearby, were also molested. In his final noting on the Mashali Mohalla incident, Rammohan has stated: "It is clear that the BSF entered the houses of innocent people and shot at totally innocent civilians, killing eight men and injuring three others. Shooting a defense-less lady was a particular cowardly act."

Rammohan adds, "The weapons and empties claimed to be recovered from the houses of the civilians were planted by Sharma and the others. A ballistic examination of the weapons seized from the BSF showed that these weapons to have been issued to these people. What more documentary evidence is required?" The documentary evidence in the case reveals that the shoot-out occurred when the BSF party decided to "retaliate" due to an ambush laid by militants in Mashali Mohalla the same night. According to BSF records, there are eyewitness accounts of BSF personnel confessing that it was the DIG himself who gave the chilling "Aag lagao. Mere ko dead body chahiye", ordered to his men. Further eyewitness accounts claim that after issuing this order, DIG Sharma left the spot.

Five minutes later, Mashali Mohalla was resounding with the wails of hysterical women and children. Mehbooba, one of the widows of Mashali Mohalla, told the court of inquiry that she first heard the sound of vehicles screeching at her door and some men shouting, "Pakistani Kutto, Bahar ajayo" (Pakistani dogs, come out). After this she heard sounds of rapid-fire and the shattering of windowpanes. Her husband, Bashir Ahmed Baig, 60,was sleeping by her side. Within minutes, the door was broken down and the BSF Jawans stormed in. They pulled off her clothes. In the meantime, she heard shots in the other room. Her youngest son, Izaz, had hidden himself under a table and was dragged out. One of the BSF men shot him too. Mehbooba ran to other room to find her husband, older son Muzzafar and a guest Abdul Rehman, all bleeding from bullet-injuries. Ten minutes later, a turbaned BSF officer returned. Seeing a new face in uniform, Mehbooba ran wailing to him, only to be shot at on the left side of her chest. She wrapped a quilt around herself and lay near the body of her husband. Her youngest son died on the way to the hospital.

Abdul lived to tell the tale though he lost his left eye. The house was then set on fire. Tasleema, the other Mashali Mohalla widow, has also given a graphic account of the massacre at the hands of the BSF. She has stated that the BSF personnel came to the first floor of her house and opened fire. She hid under the bed when she was pulled out by a BSF jawan, who ripped her cloths and tried to force him self on her. It was the whistle from DIG Sharma a signal to end the "operation" which Tasleema says she her self heard, that saved her from further humiliation. She stepped out only after the firing stopped to see the bodies of her father, Ghulam Qadir Magloo, and her two brothers, Mushtaq and Ahmed Magloo, lying on the ground, riddled with bullets. By their side was their neighbour, Farooq Baig. All of them were dead. The youngest witness for the BSF's court of inquiry is Baby Jaan, Farooq Baig's 15 year old daughter. She told the court of inquiry how the Jawans attempted to molest her when she was cowering under the bed. A BSF officer pulled her out but disgusted with her hysterical screaming, cut open her right cheek with a knife, spat on her and left.

"Are you sure I said this?" Contacted by the Indian Express, accused additional DIG J K Sharma to comment. During the court proceeding, however, he claimed he never said, "Set the place on fire, I want dead bodies." When he cross-examining the prosecution witness, he asked: "Are you sure I said those words? In this regard, it may be mentioned that it was a dark moonless night". The witness replied, "It was indeed a dark and moonless night and there were a number of personnel present but I definitely heard the command". Sharma also claimed that the "reinforcement parties that went to the Mohalla did not fire at all due to his proper command and control. Ironically, one eyewitness, whose father and two brothers were killed that night, said a BSF jawan ripped her clothes and tried to force himself on her. It was the Sharma's whistle- a signal to end the "operation" which saved her, she said Sharma has also been charged with molestation.

(Indian Express, New Delhi 2, July 1998)

Traumatic Metamorphosis

Torture is reshaping Kashmir ethos

Torture might be a good off beat idea for socialites and celebrities tired of money, market and Mafia but the seven letter word is part of the system that governs Jammu and Kashmir. India is one of the 72 countries where torture is used as a mean of interrogation and suppression, mostly by the rulers who want to stay in power. Rulers elsewhere might not be using this tool so widely with impunity, as it is prevalent in Jammu & Kashmir. No ruler, so far, could think of retaining valley without the lust for torture. Here, one can imagine places without guns, grenades and garrotes but nobody can imagine of a place where there is no torture- physical torture in custody or captivity. It is because of torture that a Kashmiri doctor can claim to be a distinguished one among all his counterpart because he/she has treated people who would have been a challenge to the advanced medical fraternity across the globe.

Again because of this so many people have developed a belief in Awagamun, the theory of reincarnation, because for them it was a second life they lived after fighting torture in the hospitals. Torture infect has re-shaped life here and proved the time tested belief that history bestows endurance to the races which are plunged into darkness of confrontation. If tacit psychological trauma is added to the word, it automatically come out of the detention centers, police stations and dungeons of armed people and becomes a part of the society that was coerced to undergo metamorphosis during last so many years. But this aspect is beyond the scope of this piece of writing. Torture is defined as infliction of severe physical pain upon a person in order to force him against his will or to punish him. So many believe torture is a pain by which guilt is punished or confessions extorted. Academic interpretation of torture notwithstanding, it has been here for centuries. With the change of systems, rulers and the people, the phenomenon remained unchanged though its magnitude varied every time. It always existed like time. In fact, most of the post-partition regimes where known by the police generals and not by the rulers. And those studying the genesis of the ongo ing crisis have found traces of torture in the minds of those who challenged system, though for a different reason. Here torture played its role in making Kalashinkoves the reality of this millennium. Militancy surfaced at a time when torture was at its peak. And after local police surrendered to a situation in which they were viewed aliens to the system, various security agencies became their masters on ground. Since militancy had made its targets in the existing intelligence network like IB, the security forces operated in a way much akin to a blind man trying to hit birds. For more than two years, there were more misses than hits as they had to groom their own intelligence gathering systems. Usually they were operating on gut feeling. A particular area was cordoned off, people were summoned (mostly dragged) out, assembled at a particular place. Among the entire lot they would segregate the well built, bearded and those wearing traditional Khan dress. They were summarily "treated" in their camps by all the means the "interrogators" could think of. At the fag end of torture, the victims could start pointing the fingers of suspect from one neighbour to another. This way they sometimes netted the right fish and even reared their sources. After the intelligence network revived completely and even outfits of surrogate soldiers were launched, torture continued unabated, though certain individuals commanding various posts did change with the changing scenario. In peacetime torture is limited to either police stations or the villages housing opposition. But in wartime every place where there is presence of olive greens there are apprehensions of it becoming a torture centre.

But Kashmir has already attained this status, though officially it is not war, it is proxy war. Security forces are a ubiquitous species and wherever they are, they have rooms for "questioning" in addition to the quarter guards and the detention rooms. Kashmir's biggest interrogation centre was in Badamibagh cantonment. Much after came the notorious Papa series and the Kotbhawal. This is debatable whether or not the twin laws- Disturbed Areas Act and the Armed Forces Special Powers Act,permit the army and various para-militaries to operated their own interrogation centers and to disobey the apex court guidelines about arrests and the subsequent follow-up, but this is fact that all the agencies ran their own network of lock-ups and interrogation centres in the past and are yet to give it up. Police run Joint Interrogation Centres (JIC) and the prisons of various status are the only translucent part of the wider prison network that operates in Kashmir. Gone are the days when two police interrogators will appear in a lock-up and start questioning the accused. One would behave harshly and another will try to befriend the accused.

This way-called Friend and Foe method, they would extract the inner from the detainee. Now, we have all the crude, inhuman and primitive methods of torture, which does not literally the third degree. The 'interrogators' (there is no specialist in a unit anywhere and usually it is the job of most close one to the CO) would barge into the cell with ticking jack boots to the concrete ground and after kicking the man here and there, he would have to pass through a series of tormenting experiences. The series include roller treatment, administrating electric shocks at the most sensitive spots, hanging upside down, forcing to take a lot of water with penis tied tightly, being knocked down with four to six persons over him, had chilies in his rectum and sometimes a rod as well (cog needle method), keep on standing without closing his eyes for days together, get his nails, hair and beard forked out, have touches of cigarettes on his body, sometime buttocks ironed, and remain naked for days together with a small pot for his fecal matter. The detained are supposed to maintain the timetable of going to bathroom and there are cases when there is no permission to take baths for months together. They would some times be provided a pyjama without a belt.

In Kashmir, the methods of interrogation would change with weather, places, individuals and even forces. During winters and more often on borders those detained would be asked to walk bare foot on snow. This would lead to frost bite and finally to the amputations. One security officer operating in remote north would ask the person to dig a grave and he would leave him buried up to his throat till he accepted what the interrogator sought. This however, was an exception. Preventing detainees from routine meeting with the family members and providing misleading information about his female relatives has all along been the worst psychological torture and it is yet in progress.

In isolated cases heart rendering torture methods were used by the interrogators to get the confession of their liking. During initial days of militancy, the detainees would be given food contaminated with dead insects and pebbles. A son, once, was ordered to suck the penis of his father. Another father was forced to undress while his wife and daughter watched. Even an officer urinated in the month of militant. And during a surgery of a detenue was stolen. But these all were isolated cases which never showed a particular pattern. In countless cases, the detained could not afford the scale of torture and died. Against just four cases of death in custody in 1989, the government has received 1030 such cases. Various opposition groups, however, put the number of deaths in custody at over 4,000. So many of them died of suffocation when the interrogators checked their heads in water. There were so many cases in the Dal lake when the Papa-II interrogators would throw young men into the lake and prevent him from coming up, unless they died. The cases of Acute Renal Failures (Rabdomylasis) are in addition to all these phenomenon. Hundreds survived the physical vandalism with disabilities and psychological problems. Almost every second person who was administered electric shocks had to be on specific medication for longer periods in order to avoid permanent impotency. After the government managed the revival of police and launched the Special Operation Group (SOG), so many were expecting things to be better behind the bars.

It never happened. In fact a youth who was arrested by SOG had all his four appendages amputated after his release and perhaps that was the only one case that could explain the SOG management. Even any visitor to the SOG lock-ups can see a cries cross of nylon ropes dangling down the ceiling giving an impression of the worst human circus where cries replace laughter. After International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) finally managed its arrival to Kashmir, so many were of the view that the life in luck-up will be a bit easier. But the MOU they had signed with New Delhi limited their activity to the jails and the JICs. The ubiquitous security forces interrogation centers were off their activity. Same was the case with the directions High Court passed in a writ petition filed by slain civil libertarian Jalil Andrabi. Because it was limited to the situation prevalent in the JICs and all types of Jails.

Though the situation was being periodically reviewed by these district committees, the system collapsed after Jalil vanished. The most unfortunate aspect of the widespread torture by the custodians of power was that it was targeted against the civilians in general. There is a strange justification being given by some honest officers. When a person is being picked up on suspicion or on identification by any security agency, they say, the interrogator uses the routine methods. Those who are really involved and have anything to share just start revealing well before they are treated in real terms. Since the civilian has nothing to offer, the interrogators go on asking and using the routine methods of torture. They finally emerge as the victims of lock-up. In the courtroom, police have failed to prove the accused as a criminal. And those who are aware of things within an outside the lock-ups say the torture is one of the reasons. While a persons agrees to sign a forced confession, he does it just to evade more custodial violence upon him. After the case is heard in the court, the prosecution fails to prove even an iota. Perhaps that is why the security forces have accepted killing of people in fake encounters as a norm but has police the authority to punish a person for the crimes he may not have committed? At the same time there has been torture from the other side as well. The methods of burning stoves under captive buttocks was a routine phenomenon.

The were cases of people being cut to pieces, blasted, left crippled and in one of the cases a person was forced to survive while iron needles were pierced through his entire body. One person was freed after his tongue was cut who later committed suicide. There are score of unreported cases, which would send ripples down the spines of Hitler of history. Though everybody has been tortured by one way or the other, there has been no mass movement by the people so far. Reaction continues to be limited to the extent that civil libertarians just report in, if and when they wish.

(Report:Kashmir Times, 29 June 1998)

Paradise lost under the threat of war

By David Graves in Srinagar

AS Pakistan carried out a second round of nuclear tests at the weekend, Indian security forces in Kashmir continued what they call their "proxy war" against Pakistani-backed Muslim separatists, in which an estimated 30,000 Kashmiris and security forces have died.

Yesterday, officials said Indian troops had killed seven Muslim guerrillas. Muslim militants had killed a relative of a former Indian home minister, the police said, adding that a brother of the politician was reported missing.

Six of the guerrillas, members of the Afghan-dominated Harkat-ul-Ansar separatist faction, were killed when Indian troops cordoned off a village in the Poonch district yesterday, according to a military spokesman in Srinagar. The seventh Muslim guerrilla had been shot by soldiers in the southern Kashmiri district of Anantnag, he said.

Meanwhile, a state government spokesman said that during the night Pakistani troops had opened fire on a civilian bus and a village in Kashmir from across the border. The region is on the cease fire line between India and Pakistan; two of the three wars they have fought since independence 51 years ago have been over Kashmir. Tens of thousands of troops from both sides now face each other across mountain tops and rugged valleys. Artillery and mortar exchanges are regular occurrences.

In the troubled state that both countries claim, boatmen ply the Dal lake in the Kashmir Valley in gondola-like vessels used for fishing and carrying fresh vegetables to markets. They eke out a meagre existence 50 miles from the border. After seeing Dal Lake, the Mogul emperor, Jehangir, is said to have written: "If there is a paradise on earth, this is it." One boatman, Lassa, said: "This should be such a peaceful place on earth. To think that Pakistan and India are carrying out nuclear tests in the name of fighting here is crazy." During the Raj period, the British escaped the searing heat of the North Indian plains to the hundreds of houseboats there, which are still moored on the lake. With names such as Clermont, Buckingham Palace and Clifton, these creaky, chintz-filled floating cottages evoke memories of a bygone era. But many of the boats are now empty, their paint peeling and the livelihoods of their owners at risk. Tourists have been scared away because of the fighting. Until 1989 when the violent disturbances that have scarred Kashmir broke out, the Himalayan State was India's greatest tourist attraction after the Taj Mahal. Some 600,000 Indian and 60,000 foreign visitors went there every year. Now, wary of the violence and the kidnapping of foreigners - six tourists, including two Britons, were abducted in 1995 by an extreme Muslim group called Al-Faran while trekking in the hills - they have stayed away from Kashmir. Senior Indian officers said there were signs of Pakistani troop movements on the border of the Muslim-dominated State last week fore Islamabad announced the first of its nuclear tests on Thursday. The situation has since stabilised. They also claimed that they were winning the "proxy war" against the extremists in Kashmir, many of were mercenaries from Afghanistan and Sudan. Curfews had been lifted, schools reopened and shops were staying open beyond nightfall, although there was still a heavy military presence in the shops, mosques and alleys in Srinagar, the state's summer capital. A lieutenant at the field headquarters of the elite 70 Brigade, whose commandos have been hunting down the extremists in the hills surrounding the Kashmir Valley, said it was only a matter of time before they had eliminated them completely. He said: "We have them well and truly on the run."

INDIA and Pakistan traded more insults yesterday in their bitter war of words over the nuclear testing carried out by both countries, each claiming that their atomic weapons were superior to those of their arch rival. Indian Ministers also poured scorn on Islamabad's claim to have detonated six nuclear devices in two rounds of tests, while senior Pakistani officials made conflicting statements themselves about the number of weapons exploded during the second test on Saturday. Despite both countries issuing conciliatory statements about being willing to begin talks with the other about reaching a "no first use" the intense rivalry and one-upmanship continued between the two neighbors, who have fought three wars since independence from Britain 51 years ago.

Although New Delhi and Islamabad both said they intended to halt nuclear testing, each said this was not definite because of the tense situation. India issued a strong protest to Pakistan's high commissioner in New Delhi after claiming that one of its diplomats in Islamabad was beaten up in front of his official residence yesterday. George Fernandes, the Indian Defence Minister, challenged Pakistani claims that it had conducted five tests last Thursday. He insisted that only two devices were tested, which were no match to India's five tests on May 11 and 13. Mr Fernandes said:"Everything that we have learned about their nuclear tests shows that they are nowhere near where we are." US Intelligence officials also said they believed that only one or two devices were exploded. In Islamabad, however, Pakistan's leading nuclear scientist said the country's devices were more efficient and reliable than those of India. Abdul Qadeer Khan, the so-called father of Pakistan's nuclear bomb, said the country could deploy its nuclear weapons within days. Its Ghauri missile, with a range of 900 miles, could devastate Indian cities. He disputed India's claim that it had exploded a thermonuclear device among the five it says were tested last month. Pakistani scientists and engineers had taken only a week to prepare for the tests Islamabad conducted. Pakistan had used "a very high-tech enriched uranium technology". The Indians had used plutonium technology, which was "very dangerous and cumbersome". Mr Khan said Pakistan could deploy nuclear weapons within days.