Kashmir Profile

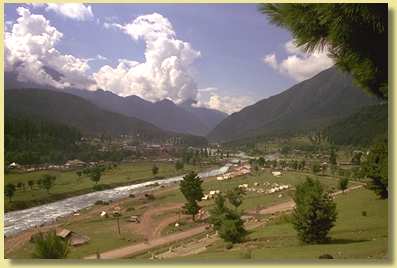

Kashmir was "once a tourist's paradise," states journalist Surinder Singh Oberoi, "one of the greenest and most temperate spots in the Himalayas-- beautiful beyond imagination." Even now, despite two wars on its soil and a decade-long insurgency, Kashmir is still considered the most attractive area in the region. However, Kashmir's strategic and political value far outwighs its aesthetic value: the Kashmir Valley controls one of the most important of the Himalayas passes, and the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum rivers all begin in Kashmir, rivers that Pakistan depends upon for water. "Greater Kashmir," that is, both Pakistani- and Indian-controlled Kashmir, also provides access to China, Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. It is not hard to understand why Kashmir has been a source of contention and conflict between Pakistan and India for half a century.

The conflict over Kashmir is as old as India and Pakistan themselves. Faced with rising nationalism in their colonies and unbearable burdens, in 1947 the British Empire made preparations to shed the "Jewel of the Empire," India. Under the "Two Nations Theory," a separate state would be created for the subcontinent's Muslim minority, forming the modern state of Pakistan. At issue, however, were over 500 semiautonomous princely states. Most quickly decided to accede to either Pakistan or India, depending on their location and ethnic makeup. Three, however, did not wish to join either. Two of them, Hyderabad and Junagadh, had Hindu majority populations and were within Indian territory, but were ruled by Muslims. India quickly incorporated them by force.

This left only the state of Jammu and Kashmir, commonly known simply as Kashmir. Kashmir posed special problems. Kashmir had a Muslim majority population but a Hindu ruler, and borders with both India and Pakistan. The maharaja of Kashmir did not wish to be incorporated by either state, but was threatened by a Muslim uprising aided by Pakistani tribesmen. In October 1947, the maharaja of Kashmir signed the Instrument of Accession of Kashmir to India, which Pakistan maintains was secured by fraud. This action has led directly to two wars between the countries, and continues to cloud their relations to this day.

India and Pakistan have fought three wars against each other since their birth, two of which have been over Kashmir. The first, the war of 1947-48, started as part of a diplomatic and military effort by Pakistan to overturn the Instrument of Accession. Pathan tribesmen attacked Kashmir on October 22, 1947, and India deployed infantry units to push them back. As they moved closer to the Pakistani border in 1948, regular Pakistani units joined in the fighting, leading to a full-scale war between the two countries. India, believing that Pakistani support of the tribesmen must be cut before the conflict could end, sought UN mediation, leading to a cease-fire on January 1, 1949. The UN-brokered cease-fire gave control of 65 percent of Kashmir to India and 35 percent to Pakistan, which called its section Azad (Free) Kashmir, and was to be followed by a UN-monitored plebiscite to decide the fate of Kashmir. This plebiscite was never held.

The second Indo-Pakistani war was fought without a formal declaration. Pakistani guerrillas infiltrated Kashmir in August 1965 and began to skirmish with Indian forces, quickly leading to serious clashes between the armed forces of the two countries. After major encounters launched by both sides, India controlled the majority of Kashmir, and the UN Security Council unanimously called for a cease-fire. The Soviet Union brokered an agreement between the two countries, known as the Tashkent Declaration, which restored the status quo antebellum.

Indian control of the majority of Kashmir led to a serious problem for Pakistan-- the division of Pakistan into what were known as the East and West Wings. The people of these two regions were separated by culture, language and geography, and a large disparity existed in political and military representation. Although West Pakistan asserted that a shared religion and fear of India would hold them together, this was not to be the case. In 1971 the East Wing of Pakistan seceded and was aided by Indian forces, creating the independent state of Bangladesh. This interference, as Pakistan saw it, did nothing to ease tensions between the two rivals. Fighting also occurred along the cease-fire line in Kashmir, leading to the Simla Agreement of 1972. The cease-fire line (now known as the Line of Control) was altered slightly, and India and Pakistan agreed not to use force in Kashmir. This agreement also called for India and Pakistan to resolve the issue of Kashmir bilaterally. Partly because of this agreement, India held parliamentary elections in Kashmir on May 7, May 23, and May 30, 1996. These elections were widely supported in Jammu, the Hindu-dominated southern section of Kashmir, but foreign observers were denied the right to monitor elections, and Pakistan denounced the elections as a fraud. Tehree-ul-Mujahideen, a pro-Pakistan separatist group, called the elections a "ploy" to take attention away from autonomy, and Amanullah Khan, the chair of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), stated that "no patriotic Kashmiri individual or organization will let India succeed in hoodwinking the world about Kashmir by claiming that Kashmiris enjoy democratic rights."

The greatest threat to India's rule in Kashmir today does not come from Pakistan, but from Muslim Kashmiris. When the parliamentary elections were held in 1996, Hurriyat (also known as the All-Party Freedom Conference), an umbrella group of 32 pro-independence political and religious groups, attempted to strike, with some success, and the Jammu and Kashmir Islamic Front set off a bomb in New Delhi, killing 25 people. Today there are several dozen separatist militant groups, and over 20,000 people have been killed in the fighting.

India involved itself deeply in Kashmiri politics during the '80s, embittering many Kashmiris who were waiting for a plebiscite. Farooq Abdullah of the overwhelmingly Muslim National Conference was elected in 1982 as Chief Minister of Kashmir when his father, Sheikh Abdullah, died. Two years later he was deposed by his brother, Ghulam Mohammed Shah, who was backed by New Delhi. New Delhi decided three years later to reinstall Farooq Abdullah, who supported the granting of autonomy without weakening ties to India. He described the accession of Kashmir to India as a "historic reality which no power on earth can undo." Abdullah was elected to another term in what was widely considered a rigged election, causing the Muslim United Front to accuse the government of vote fraud. Several leaders of the Muslim United Front were jailed and fled to Azad Kashmir upon their release, where they set up guerrilla groups to oppose the Indian government. Pakistan has been generally suspected to arm and train the refugees, though Pakistan claims to give only political and moral support.

In July 1989, bombs exploded at three sites in Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir. In December of the same year, the daughter of the Indian Home Minister was kidnapped, and freed only when India released five militants. Combat began in earnest following this apparent victory. Guns from Pakistan and Afghanistan flowed to the rebels, who called themselves "mujahideen." In response, India appointed a hard-line governor charged with putting down the revolt. Abdullah resigned in protest, which prompted New Delhi to take direct control of the region.

The Indian government has been accused of severe human rights violations in connection with the crackdown, which has been largely ineffective. A common tactic is the cordon-and-search, which is employed whenever a separatist is captured. A neighborhood is cordoned off before sunrise and awakened by loundspeaker, while the informant is placed in a car with dark windows. A house-to-house search is then conducted. All the men in the community are marched past the informant, who points out guerrillas. Amnesty International has released a report which states that "the entire civilian population is at risk. Torture includes beatings and electric shocks, hanging people upside down for many hours, crushing their legs with heavy rollers, and burning parts of their bodies."

Atrocities are not limited to the Indian government, however; non-military targets are commonly chosen by the separatist groups, and kidnappings and assassinations are common. In 1996 separatist guerrillas kidnapped 19 journalists, including several foreign journalists. They were freed by counter-insurgency forces of the Indian Army after a ten-hour standoff.

Both Pakistan and India have responded to increasing tensions in Kashmir by reinforcing the Line of Control with troops. Border clashes are common, including artillery fire. The most famous deployment is at Siachin Glacier, where temperatures remain below freezing year-round. Despite heavy exchanges of fire, more soldiers have died of exposure than of enemy gunfire. Pakistan has also been accused of using the cover of gunfire to slip Pakistani troops into Kashmir.

Moreover, Pakistan has become the unwilling home of Muslim militants from Arab countries, including Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the Central Asian states, and many Far Eastern states. India has accused Pakistan of recruiting these militants as mercenaries to fight in a proxy war in Kashmir. India has also accused Pakistan of trying to "internationalize" the conflict in violation of the Simla Accord.

It is unrealistic to expect India to allow a plebiscite in Kashmir unless the uprising becomes so expensive to contain that India no longer wants to rule Kashmir. In an open plebiscite, the Muslim-majority Kashmir would likely either accede to Pakistan or declare independence-- which would open the door to other Indian states which desire independence. Prime Minister Narasimha Rao supports the idea of internal autonomy within India, with elections to be held at some time in the future. Pakistan, for its part, does not supply the rebel forces simply in order to create an independent state, even a Muslim one. Pakistan intends to incorporate Kashmir into Pakistan. Pakistan supports implementation of the UN Resolution of 1948, which calls for a plebiscite under UN supervision with two choices: join India or Pakistan. Kashmiris, however, are a divided lot. Among Muslims, more than half support full independence, with the remainder wanting mainly to join with Pakistan. The other ethnic groups in Kashmir mostly wish to remain with India. However, the longer the insurgency continues, the more support for independence is likely to grow.

Militarily, Pakistan finds itself severely outnumbered, sometimes as much as 3-to-1. The Pakistani Army recognizes this, and pursues a policy of conciliation while maintaining determination to prove itself should war break out. In addition, Pakistan would face a severe shortage of supplies in the event of another war. Because of these considerations and a lack of depth of defense, Pakistan has developed a strategy of "offensive defense," stressing a quick preemptive strike to disrupt enemy advances, inflict crippling losses, and gain territory to exchange for peace. The Pakistani Air Force and Navy are consigned to defensive roles.

One important consideration in Pakistani-Indian military relations is the presence of nuclear weapons. There is a high probability that both states possess nuclear weapons and are capable of delivering them to targets on the other's soil. India in fact exploded a nuclear device as far back as 1974. Pakistan is believed to have nuclear weapons as well, probably M-11 missiles from China. Pakistan is also believed to have nuclear weapons deliverable by airdrop from C-130's or F-16's, both planes in the Pakistani Air Force. The US F-16's delivered to Pakistan had the wiring neccessary to launch nuclear weapons removed, but this is easily reinstalled, and has probably already occurred.

The issue of Kashmir would be relatively unimportant if it were not for the presence of nuclear weapons and the political ties that both Pakistan and India have with other states. Pakistan was a Cold War ally of the United States, recruited at the time of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In 1959 the United States signed an Agreement of Cooperation, in which the United States committed itself to the "preservation of the independence and integrity of Pakistan," agreed to take "appropriate action, including the use of armed forces, as may be mutually agreed upon . . . in order to assist the Government of Pakistan at its request." The agreement does not specifically address India, nor did the United States intend for it to apply to India (the agreement was designed to deter aggression from the Soviet Union), but Pakistan has chosen to interpret it in this manner.

The US relationship with Pakistan, however, has been rough. US support has waxed and waned. The United States cut off delivery of military equipment in 1990 under the Pressler Amendment, which prohibited assistance to Pakistan if the President of the United States did not certify that Pakistan was not in possession of a nuclear device, when former Prime Minister of Pakistan Nawaz Shari stated that Pakistan possessed a nuclear weapon. Because of this uncertain support, Pakistan has turned to China to fulfill its security needs, culminating in the delivery of Chinese M-11 missiles, which have a payload large enough to carry a nuclear warhead. Pakistan has also forged close relationships with many states in the Middle East, promoting itself as the defender of Islam.

India's closest Cold War ally was the Soviet Union. Although India has long pursued a strategy of non-alignment, and indeed promoted itself as the leader of the Non-Aligned movement, realpolitik concerns, including tension with China and the US-Pakistani relationship, drove India into the Soviet Union's arms. Ties with Russia remain strong since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Both states are active in the international arena. India and Pakistan are members of both the UN and SAARC, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. Pakistan, due to its weakness relative to India, has increasingly turned to the UN to mediate in disputes, particularly in Kashmir, despite the Simla Accord. India has used the UN to avoid unilateral imposition of superpower will and to focus attention on the problems of developing countries. SAARC, however, will be ineffective in mediating the dispute over Kashmir, because its charter forbids it from discussing bilateral disputes amongst members.