REAM'S STATION

August 22-25, 1864

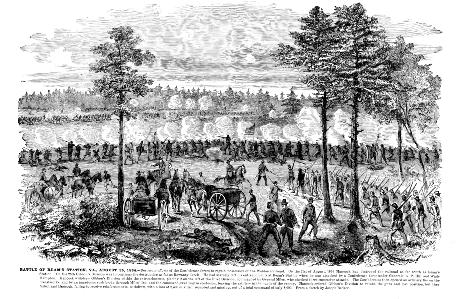

Reams' Station, Va., Aug. 22-25, 1864. 2nd Army Corps, Gregg's and Kautz's Cavalry. The battle of Reams' station was a part of the operations about Petersburg during the seige. After Gen. Warren's expedition against the Weldon railroad on Aug. 18-21, the Federal intrenchments were extended from the Jerusalem plank road to connect with Warren's new position on the railroad. This railroad was the chief line of supply for the Confederate army, and although Warren held it at Globe tavern, it was still open on his left, so that supplies could be transported by wagon in a day's time to Petersburg. Gen. Grant, therefore, determined to destroy the track as far as Rowanty creek, about 20 miles south of Petersburg, which would force the enemy to haul his supplies from Stony Creek station by way of Dinwiddie Court House, a much greater distance. Maj.-Gen. W.S. Hancock, with the 1st and 2nd divisions of the 2nd Corps, Gregg's cavalry division and Spear's brigade of Kautz's cavalry, was charged with the work and received his orders to that effect on the morning of the 21st, just after his command had returned from Deep Bottom. He at once took up the march towards Ream's station, Spear's cavalry having the advance and engaging in a slight skirmish with the enemy on the Vaughan road. The cavalry covered the roads leading to the railroad and by evening of the 24th the railroad was destroyed to Malone's crossing, 3 miles south of Ream's station. About 11 o'clock that night Hancock received a dispatch from headquarters notifying him that a Confederate force, estimated at from 8,000 to 10,000 men, was moving from the intrenchments by the Vaughan and Halifax roads. This was gen. A.P. Hills corps, part of Longstreet's command and Hampton's cavalry, all under the command of Hill. Slight intrenchments had been thrown up at Reams' station during Wilson's raid in June. These were now occupied by Hancock, Gibbon's division on the left and Miles, (Barlow's) on the right, the cavalry being sent out on reconnaissance to locate the enemy and develop his strength. About noon on the 25th, pickets on the Dinwiddie road were driven in and at 2 p.m. two spirited attacks were made in quick succession on his front, but both were repulsed, some of the Confederates falling within a few yards of the works. In the meantime Gen. Meade had ordered Gen. Mott to send all of his available force down the plank road to the assistance of Hancock, and about 2:30 directed Wilcox's division of the 9th corps to follow Mott. These reinforcements did not reach Hancock in time to be of any material service. At 5 p.m. Hill opened a heavy fire of artillery, taking part of the Union line in reverse. After about 15 minutes of this cannonade an assault was made on Miles' front. The attack was bravely met and the enemy thrown into some confusion, when the 7th, 39th, and 52nd N.Y., composed chiefly of new recruits, broke in disorder. A small brigade, under Lieut.-Col. Rugg, which had been stationed in reserve was ordered up to fill the gap in the line, but Hancock says in his report: "the brigade could neither be made to go forward nor fire." McKight's battery was then ordered to direct its fire into the opening, but the enemy, by advancing along the rifle-pits gained possession of the battery and turned one of the guns on the Union troops. Gibbon was ordered forward with his division to recapture the guns, but the men seemed to be panic-stricken, "falling back to their breastworks on receiving a slight fire from the enemy." Gibbon was now exposed to an attack in reverse and on the flank, forcing his men to occupy the outside of their works, and for a moment it looked as though the gallant 2nd corps, that had proven its valor on so many battlefields, was doomed to utter annihilation. In this critical moment Miles rallied a small force, formed a line at right angles to the intrenchments, swept off the enemy and recaptured the battery. Had Gibbon's officers been able to rally the men at this juncture, the story of Reams' station might have been differently told. But while the effort was being made to bring up the division an attack was made upon it by the enemy's dismounted cavalry and the whole command was driven from the breastworks. Elated by this success the Confederates advanced with the "rebel yell" against miles, when they were met by a severe fire from the dismounted cavalry on the extreme left and their advance summarily checked. Gibbon had finally succeeded in forming a new line a short distance in the rear of the rifle-pits, and to this line Gregg and Spear now retired, Woerner's battery covering the movement and dealing havoc in the enemy's ranks by its well-directed fire. This battery and troops under Miles held the road leading to the plank road until dark, when the order was issued to withdraw. Wilcox's division was then within a mile and a half of the field where it was formed in line of battle, and after Hancock's men had passed became the rear-guard. In his report, Hancock says: "Had my troops behaved as well as heretofore, I would have been able to defeat the enemy on this occasion. *** I attribute the bad conduct of some of my troops to their great fatigue, owing to the heavy labor exacted of them and to their enormous losses during the campaign, especially in officers." This was doubtless true. There is a limit to human endurance and the men of Gibbon's division had reached the limit. Marching all night of the 20th and all day of the 22nd, tearing up railroad track through the day and standing picket at night from that time until they were engaged on the 25th, the men were so completely worn out that they had lost both ambition and patriotism. The Union loss was 140 killed, 529 wounded and 2,073 missing. Hill reported his total loss at 720 and claimed to have captured 2,150 prisoners, 9 cannon, 12 colors, and over 3,000 stands of small arms.

Source: The Union Army, vol. 6