|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| From "Women of the War," by Frank Moore, Hartford, Conn., 1866, pp. 54-64 |

|

|

|

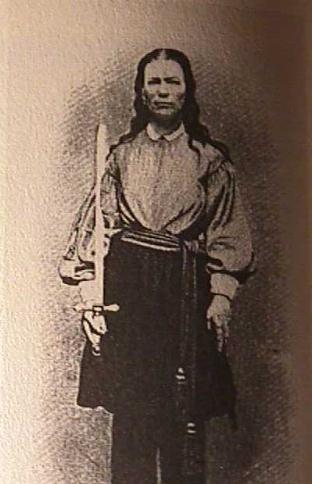

Kady Brownell, |

|

|

|

The Heroine of Newbern |

|

|

| All our revolutionary historians are eloquent in their praises of the bold heroine of Monmouth, "Captain Molly." They tell us how she was carrying water to the men of Proctor's battery on that hot and bloody afternoon in July, when a ball crushed in the skull of her husband, just as he was ramming a charge into his field piece, and he fell at her feet a bloody corpse. "Lie there, my darling, till I avenge your death!" exclaimed Molly, and seizing the rammer, she went on with the work which death had cut short, while the men cheered her all along the line. All through that afternoon, till night covered the landscape and closed the battle, Molly stood by her gun, and made good her husband's place, swabbing the piece, and forcing home the successive charges with the vigor and coolness of the bravest soldier. The next morning she was presented to General Wayne, all soiled and bloody as she had fought; and Washington gave her a commission as sergeant, and by his recommendation her name was placed on the list of half-pay officers for life. |

|

|

| The annals of our great war for the Union are not wanting of similar instances where the wife of the soldier has gone with her husband, experienced all the hardships of the camp, stood in the line with sword at her side, carried the colors into the thickest of the fight, and then, when the bloody work was over, devoted herself with the delicate tenderness of her sex, to mitigating the horrors of the battle-field. |

|

|

| Such was the brave young wife whose name stands at the head of our sketch; and such were her courage, her bearing, and her services on the plains of Manassass and at the battle of Newbern. Her father was a Scotchman, and a soldier in the British army. He was stationed far away on the African coast, in Caffraria; and there, in the year 1842, in the regimental barracks, and surrounded by the rude but kind old soldiers, her father's companions in arms, little Kady was born. |

|

|

| Accustomed to arms and soldiers from infantry, she learned to love the camp; and it was, not strange, years later, when she had come to America and married a young mechanic in Providence, that the recollections of the camp fire in front of her father's tent, as well as the devotion of a newly-married wife, and loyalty to the Union, prompted her to follow her husband, stand beside him in battle, and share all his hardships. |

|

|

| Her husband, Robert S. Brownell, was made orderly sergeant of a company in the First Rhode Island Infantry, one of the earliest regiments of three months' men who responded to the first call for troops, the day after national colors were run down the flag-mast at Fort Sumter. |

|

|

| The First Rhode Island Infantry was soon full to over-flowing. It had eleven full companies of a hundred each; and as ten were enough for a complete organization, the eleventh was formed into a company of carbineers or sharp-shooters, and the brave young wife of the orderly was made the color-bearer of this company. |

|

|

| When the regiment went into camp in Maryland, early in the summer of 1861, this Daughter of the Regiment was resolved not to be a mere water-carrier, nor an ornamental appendage. She would be effective against the enemy, as well as a graceful figure on parade, and applied herself to learn all the arts and accomplishments of the soldier. When the company went out to practice daily at the target, she carried her rifle, as well as the colors; and when her turn came, the men seldom restricted her to the three shots which were allowed to each. So pleased were they by her skill and coolness with the weapon, that she was allowed as many shots as she chose, and thus became one of the quickest and most accurate marksmen in the regiment. Nor was the sergeant's straight sword, which hung at her belt, worn as an idle form. She practiced daily with her husband and his friends in camp, till she felt herself as familiar with its uses as with the carbine. |

|

|

| When the regiment moved she sought no indulgences on account of her sex, but marched in line beside her husband, wearing her sword and carrying the flag. |

|

|

| The middle of July came, and the Union army was at length moving southward from the Potomac, its face set towards Richmond. She marched with her company, and carried her flag. On the day of the general action she was separated from her husband, the carbineers with whom she was connected being deployed as skirmishers in the skirt of pine woods on the left of the line. About one o'clock on that eventful day the company was brought under fire. She did not carry her carbine that day, but acted simply as color-bearer. The men, according to skirmish tactics, were taken out by fours, and advanced towards the enemy. She remained in the line, guarding the colors, and thus giving a definite point on which the men could rally, as the skirmish deepened into a general engagement. There she stood, unmoved and dauntless, under the withering heat, and amid the roar, and blood, and dust of that terrible July day. Shells went screaming over her with the howl of an avenging demon, and the air was thick and hot with deadly singing of the minie balls. About four o'clock, far away on the right, where the roar had been loudest, a sudden and marvelous change came over the scene. The Union line was broken, and what was a few moments before a firm and resolute army, worn and bleeding, but pressing to victory, became a confused and panic-stricken rout. |

|

|

| The confusion now ran down the line, from right to left, and the sharpshooters of the First Rhode Island, seeing the battle lost and the enemy advancing, made the best retreat they could in the direction of Centreville. But so rapidly spread the panic, that they did not rally on their colors and retreat in order. She knew her duty better, and remained in position till the advancing batteries of the enemy opened within a few hundred yards of where she stood, and were pouring shells into the retreating mass. Just then a soldier in a Pennsylvania regiment who was running past, seized her by the hand, and said, "Come, sis; there's no use to stay here just to be killed; let's get into the woods."\ She started down a slope with him towards a pine thicket. They had run hardly twenty steps, when a cannon ball struck him full on the head, and in an instant he was sinking beside her, a shapeless and mutilated corpse. His shattered skull rested a moment on her shoulder, and streams of blood ran over her uniform. |

|

|

| She kept on to the woods, where she found some of the company, and before long chanced upon the ambulance, into which she jumped; but the balls were flying too thick through the cover. She sprang out, and soon after found a stray horse, on which she jumped, and rode to Centreville. Here and at Arlington Height, for more than thirty hours, she was tortured by the most harassing stories about her husband. |

|

|

| One had seen him fall dead. Another had helped him into an ambulance, badly wounded. Another had carried him to a hospital, and the enemy had fired the building, and all within had perished. Then, again, she learned that his dead body was left in the skirt of pine woods in front of where she stood. So fully did she believe this at one time, that she had mounted a horse, and was starting back from Alexandria, in hope of getting through the lines and finding him, when she was met by Colonel Burnside, who assured her that Robert was unhurt, and she should see him in a few hours. |

|

|

| The First Rhode Island was a three months regiment, and its time expired on the 1st of August. |

|

|

| She returned with it to Providence, where she received a regular discharge; but it was only to reenlist with her husband in the Fifth Rhode Island. The fall of 1861 was a time of inaction in the army. McClellan had taken command, and for months the great Union army, with a spirit and intelligence never equalled in any military organization, and abounding in zeal for "short, sharp, and decisive" work, was month after month getting ready to move. Meantime Burnside, who was a colonel at Bull Run, had been made a brigadier, and placed in command of the Burnside expedition, whose duty it was to penetrate the country south of Richmond, and at the opportune moment to advance on Richmond from that direction, while the grand army should march upon it from the north. |

|

|

| The Fifth Rhode Island was in his force. In January Roanoke Island was taken, and the first blow struck at the rebel power. Early in March he was in Neuse River, and advancing Newbern. In the organization of the regiment Kady was not now a regular color-bearer, but acting in the double capacity of nurse and daughter of the regiment. When the force debarked, on the thirteenth, she marched with the regiment fourteen miles, through the mud of Neuse River bottom, and early the next morning attired herself in the coast uniform, as it was called, and was in readiness, and was earnest in the wish and the hope that she might carry the regimental colors at the head of the stormers when they should charge upon the enemy's field works. |

|

|

| She begged the privilege, and it was finally granted her, to go with them up to the time when the charge should be ordered. Here, by her promptness and courage, she performed an act which saved the lives of perhaps a score of brave fellows, who were on the point of being sacrificed by one of those blunders which cannot always be avoided when so large a proportion of the officers of any force are civilians, whose coolness is not equal to their courage. |

|

|

| As the various regiments were getting their positions, the Fifth Rhode Island was seen advancing from a belt of wood, from a direction that was unexpected. They were mistaken for a force of the rebels, and preparations instantly made to open up on it with both musketry and artillery, when Kady ran out to the front, her colors in hand advanced to clear ground, and waved them till it was apparent that the advancing force were friends. The battle now opened in good earnest. Shot and shell were flying thick, and many a brave man was clinching his musket with nervous fingers, and gun-barrels which were about to charge with anything but cheerful faces, when Kady again begged to carry her colors into the charge. But the officers did not see fit to grant her request, and she walked slowly to the rear, and immediately devoted herself to the equally sacred and no less important duty of caring for the wounded. |

|

|

|

In a few moments word was brought that Robert had fallen, and lay bleeding in the brick-yard. That was the part of the line where the Fifth Rhode Island had just charged and carried the enemy's works. She ran immediately to the spot, and found her husband lying there, his thigh bone fearfully shattered with a minie ball; but, fortunately, the main femoral artery had not been cut, so that his life was not immediately in danger from bleeding. |

|

|

| She went out where the dead and wounded were lying thick along the breastwork, to get blankets that would no longer do them any good, in order to make her husband and others more comfortable. |

|

|

| Here she saw several lying helpless in the mud and shallow water of the yard. Two or three of them she helped up, and they dragged themselves to dryer ground. Among them was a rebel engineer, whose foot had been crushed by the fragment of a shell. She showed him the same kindness that she did the rest; and the treatment she received in return was so unnatural and fiendish that we can hardly explain it, except by believing that the hatred of the time had driven from the hearts of some, at least, of the rebels, all honorable, and all Christian sentiments. |

|

|

| The rebel engineer had fallen in a pool of dirty water, and was rapidly losing blood, and growing cold in consequence of this and the water in which he lay. |

|

|

| She took him under his arms and dragged him back to dry ground, arranged a blanket for him to lie on, and another to cover him, and fixed a cartridge box, or something similar, to support his head. |

|

|

| As soon as he had grown a little comfortable, and rallied from the extreme pain, he rose up, and shaking his fist at her, with a volley of horrible and obscene oaths, exclaimed, "Ah, you d--- Yankee -----, if I ever get on my feet again, if I don't blow the head off your shoulders, the God d--- me!" For an instant the blood of an insulted woman, the daughter of a soldier, and the daughter of a regiment, was in mutiny. She snatched a musket with bayonet fixed that lay close by, and an instant more his profane and indecent tongue would have been hushed forever. But, as she was plunging the bayonet at his breast, a wounded Union soldier, who lay near, caught the point of it in his hand; remonstrated against killing a wounded enemy, no matter what he said; and in her heart the woman triumphed, and she spared him, ingrate that he was. |

|

|

| She returned to the house where Robert had been carried, and spreading blankets under him, made him as comfortable as he could be at a temporary hospital. The nature of his wound was such that his critical time would come two or three weeks later, when the shattered pieces of bone must come out before the healing process could commence. All she could do now was simply to keep the limb cool by regular and constant application of cold water. |

|

|

| From the middle of March to the last of April she remained in Newbern, nursing her husband, who for some time grew worse, and needed constant and skilful nursing to save his life. When not over him, she was doing all she could for the other sufferers. Notwithstanding her experience with the inhuman engineer, the wounded rebels found her the best friend they had. Every day she contrived to save a bucket of coffee and a pail of delicate soup, and would take it over and give it out with her own hands to the wounded in the rebel hospital. While she was thus waiting on these helpless and almost deserted sufferers, she one day saw two of the Newbern ladies, who had come in silks to look at their wounded countrymen. One of them was standing between two beds, in such a position as to obstruct the narrow passage. Our heroine politely requested her to let her pass, when she remarked to the other female who came with her, "That's one of our women -- isn't it?" "No," was the sneering response, "she's a Yankee -----," using a term which never defiles the lips of a lady. The rebel surgeon very promptly ordered her out of the house. |

|

|

| It is but justice, however, to say that in some of her rebel acquaintances at Newbern human nature was not so scandalized. |

|

|

| Colonel Avery, a rebel officer, soon after he was captured, said something to her about carrying the wrong flag, and that "the stars and bars" was the flag. "It won't be the flag till after your head is cold," was her quick reply. The colonel said something not so complimentary to her judgement, when General Burnside, who was standing near, told him to cease that language, as he was talking to a woman. Immediately the colonel made the most ample apologies, and expressed his admiration of her spirit and courage, and afterwards insisted on her receiving from him sundry Confederate notes in payment of her kindness to the wounded among his men. There was one poor rebel, who died of lockjaw from an amputated leg, whom she really pitied. He said he "allus was agin the war -- never believed Jeff Davis and them would succeed no how," and talked about his poor wife and his seven children, who would be left in poverty, and whom he would never see again, in a way so natural and kindly that she forgot all about the brutal engineer and the insulting woman in silk, and did all she could to make the poor old man comfortable. He was fond of smoking, and in the terrible pain he suffered, the narcotic effect of the tobacco was very soothing. Kady used to light his pipe for him at the hospital fire, and go give it to him. |

|

|

| In April Robert could bear removal, and was made as comfortable as possible on a cot on the steamship. Arriving in New York, he lay a long time in the New England Rooms; and his faithful wife, as tender as she is brave, thought only of his life and his recovery. But it was eighteen months before he touched ground, and then the surgeons pronounced him unfit for active service; and as his soldier days were over, Kady had no thought of anything more but the plain duties of the loving wife and the kind friend. The colors she so proudly carried she still keeps, as well as her discharge, signed A.E. Burnside, and the sergeant sword, with her name cut on the scabbard, and sundry other trophies of the Newbern days. An excellent rifle, which she captured, she gave to a soldier friend, who carried it back to the front, and fought with it till the war was ended. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

More on Kady Brownell |

|