My parents Torcuato Cacabelos and Eulalia Foronda both of Narvacan, Ilocos Sur, Philippines were married in 1892. Their marriage lasted until 1921 when my father died of typhoid disease. There were eight children born to them, but two died in infancy. Our eldest was sister Pausta who remained a spinster. Then brother Luis, sister Eugenia, Narciso, who was four years my senior, I came next and our youngest was Esperanza.

We lost father when I was still very young. I was 12 years old and I had a very vague memory of his face. Mother often told us that father was a good provider and a very kind and understanding parent. Mom repeatedly emphasized his great affection to everyone of us. This was a blessing that he established cohesiveness and unity in the family. This greatly helped Mom during the years. We obeyed her always.

Mom was unique. She was Eulalia Foronda before father - Torcuato - married her. She had a pleasant face and a remarkable disposition. She had a special appeal to each of us. I never heard her complain although I knew that there were difficult situations. Each of us knew that we were poor like our neighbors and so we cooperated with her wholeheartedly. That was the duty of a fatherless family to accept the guidance of the only parent we had.

Mom's sister, Auntie Borona often came with cousin Dioning to visit us, bringing good things to eat such as patopat or soman. Dioning's Papa, Uncle Ardong (Leonardo) also came now and then and always conferred with Manong Luis and offered his services whenever needed. Dioning had already finished 7th grade, while I was still fighting with the plow and those dams of our rice fields. Auntie Borona had an older daughter cousin Emilia, who was then married and we seldom saw her. Cousin Berto (Albert) was Narcis age and both came to America in 1926. We saw Manong Berto in L.A. when Jimmy was seven and we all went to Disneyland. In the early 80's I heard that he went home for his health. Mom and Auntie Borona got along well. We noticed how relaxed Mom was whenever she came to visit us. They were indeed close and very affectionate with each other. Mom loved each of us in her way. She believed in the power of prayer. She tried to transmit her love of God to her six offspring.

Farm Life

My family was very poor. Father was a farmer and he had only two small pieces of land which he inherited from my grandfather on his marriage day. He became a tenant farmer in order to support his growing family. After dad died, Luis our oldest brother, although he had a family of his own, became the manager of all the fields. He and his family took 1/5 of the harvest and gave 4/5 to Mother. Then Mother saved as much as she could.

Since primary education was free, Pausta, Luis and Eugenia only finished 4th grade. Narciso was the only one to reach freshman year high school in the Narvacan Academy. The third boy of 3 brothers and the 5th of six children, I was at a disadvantage when it came to education. I was forced to stop my studies after finishing my 4th grade in March 1921, the year father died. After finishing 4th grade in 1921, I was then twelve years old. My brother Narciso was in high school. I envied him because he was wearing good clothes. He stayed in town so he had to pay board and room which was a real hardship to mother. So when it was my turn to attend 5th grade in town, mother said that I cannot go because there was no money. She explained to me that if I attend 5th grade in town, I had to have shoes, clothes, books, paper, pencil, etc. In addition money for board and room. That was a great expense for the family since Narciso is hardly getting along.

Farming is a hard, backbreaking occupation. Besides the work in the farm, the cows and carabaos must be fed and corralled. There seems to be no end to it except on Sundays. I never liked it. So, I learned to farm with Luis my older brother since our father had died when I was only twelve. For five years I was taught to plow, harrow, plant and harvest rice. Also I learned to plant vegetables after the rice had been harvested. Eggplants tomatoes and beans were our principal crops. Early in the morning, I would ride our carabao and go to the high lands. There my carabao would graze as much as it could. Meanwhile I would stay in a shade to avoid the heat of the rising sun. Many times I would find myself daydreaming of being in the 5th grade wearing shoes, long pants and clean clothes. During the wet season in early July, brother Luis and I would prepare our little fields for planting rice. This required plowing. With a wooden plow hitched to the carabao, I would guide the plow starting from one end of the field to the other. The trouble with the field is that it was not flat. Usually the fields are inclined. Every 30 feet or so a dam is necessary to hold water. Our field had 4 dams. For me to lift the plow over the dam was difficult. Too heavy. Very often, I would not be able to lift the plow so that I would make a dike in the dam. Brother Luis would sympathize with me and good humorously remark: "Not again!"

Narciso goes to the United States

Early in the 1920's, many Filipino pensionados came back from the U.S. with bachelor degrees and even a few had masters. They were the envy of all especially the young students because everyone of them found immediate employment in the public schools as classroom teachers or as principals. They exemplified real success as a reward of their hard earned studies. They were looked upon as leaders in their respective communities. Most parents particularly the poor remedied the passage of their sons to come abroad to study. This influx of Filipino students to the United States lasted from the 1920's up to 1935.

When comparing the Filipino pensionados who succeeded so well in their studies in American universities to the poor showing of those who came on their own or prompted by their parents, I must explain the difference between the two situations. In the first situation, the pensionados were bright students sent by the Philippine Bureau of Education upon recommendation of their respective principals. As pensionados, these students entered the universities where they were sent without worrying about their tuition, books, clothes, food and lodging. The Bureau subsidized them. In return, each pensionado contributed richly to Philippine education. In the second situation, those who came for higher education were self-supporting. From the thousands that came, only a few actually finished college. Their parents who sent them abroad believed that since Pedro's son, Manuel succeeded, their son too could do the same. They overlooked the important ingredient of a college student to stay in school. Besides his health and brains, he needed clothes, tuition, books, food and shelter. The two situations appear without parallel.

Mother was one of those parents eager to have a son succeed abroad. Narcis was a sophomore in Narvacan High when mother mortgaged a piece of land for his passage to Seattle, Washington, U.S.A., in 1926. The Philippines was under U.S. sovereignty and any healthy Filipino can come to the U.S. Having been found healthy, the Cacabelos family gave him a despidida party with prayers for his success. Narciso practically spent everything in his first year in high school. So that was the main reason mother wanted Narciso to succeed in America so that he may bring honor and financial help to the family. After Narciso left, the family remained poor and I was not yet allowed to attend 5th grade in town.

Fernando Cacabelos, Uncle Andong, lived in barrio Quinayan, about two kilometers away. He was a tenant farmer of the rich Crisologo family of Vigan. He knew how eager I was to continue my studies. Also he was very aware how frustrated I was behind the plow. Uncle Andong loved my father very much, I was told much later, and he did not want his nephew Rufino to become just a farmer. He came to mother and persuaded her to let me go to Vigan to be a schoolboy to attorney R. Crisologo.

At Seminary College in Vigan, the capital of Ilocos Sur Province

Uncle Andong persuaded Mom to let me go with him to see Attorney Ramon Crisologo, a wealthy bachelor who was famous for his charity to needy boys from poor families. How Uncle knew this about Attorney Crisologo's passion to educate poor boys was never revealed to Mom or to me. Suffice to mention here that after interviewing me and learning my eagerness to study, he accepted me for a year's trial and find out if I was really a good student. So at age 16, I became the 9th muchacho in that rich family. The muchachos (houseboys) did odd jobs for the rich family, such as clean the stables, feed the horses, help in the kitchen, and run errands to their many equally rich friends of Vigan. We really did not do much work in the Crisologo household. Each of us took turns in shining the beautiful sala floor every other day and of course wash dishes as needed daily.

In return for being a houseboy, I was sent to school by Attorney Crisologo and thus finished my 5th, 6th, and 7th grades in the famous Immaculate Conception Seminary - a school admitting primary children through seminarians to enter the priesthood. I was very happy as a school boy. The work was easy for me and very rewarding. As a muchacho, I had my room and board, clothing and schooling free. As my guardian for attending the Immaculate Conception Seminary, Attorney Crisologo had to sign my report cards at the end of the year. I passed the 5th grade with honors, second only to Simeon Ramos our valedictorian. He was so impressed with my high grades that he had told me over and over that he will send me to the Ateneo de Manila and follow his footsteps as a lawyer.

I was not really smart, but my grades were good because I was the oldest in the class of 45. I had to struggle hard to attain a salutatorian standing. Attorney Crisologo was delighted and very surprised at my achievement. He spoke to us, (Francisco) Icco, (Tomas) Marong and me. There were 3 of us being sent to school by our Apo. He told us that as long as we get good grades he will send us to the University of Santo Tomas in Manila. Each of us thanked Apo Ramon. As for me, he rewarded me with a new pair of shoes besides shirts and pants for being second in my 5th grade class.

So the three of us vied for Apo Ramon's attention. I studied harder in the 6th grade, but somehow Simeon was always ahead of me. This happened in the 5th grade and also in the 6th. Apo Ramon showed no favoritism to Marong, Icco or me. He delighted in sending us to school all at his expense. Apo urged us to attend to our lessons. He told us that he was an outstanding student. He wanted each of us to do the same. Apo could not suppress his pride for me because I was doing better than Icco and Marong. He wanted me to continue my High school at the seminary college then to Santo Tomas in Manila later.

The American Dream

At the end of my 7th grade, I was once again beaten by Simeon Ramos. However, I enjoyed being second to Simeon in all the Intermediate grades. Simeon's father was an outstanding attorney. His family belonged to the elite group of landed people of the province just as the Crisologos of Vigan. Simeon came to class in a caratella since he lived twelve blocks away from the seminary. In my case, the Crisologo mansion was just across the plaza from the seminary. Simeon and I corresponded all through the years. His scholastic achievements had a great influence on me to keep up with my studies. Besides, I had solemnly promised Mom that I shall do my utmost if I went on to further my education. These were the motivators for me not to be too far behind Simeon and to fulfill my word to Mom. In 1945 in a soldier's uniform I had the pleasure of seeing Simeon in his Manila home since 1929. He continued from year to year as valedictorian of his class, even in his four most challenging years at University of Santo Tomas Law School. After graduating with honors, the faculty of his alma mater instantly included him in their elite circle. He informed me that in the first few years he instructed the freshmen law classes. Also, out of the 45 in our 7th grade class, 4 became lawyers, one a priest and many did not go to college. In our brief meeting, he congratulated me once more of my success in America. He was knowledgeable of the thousands of young men who did not continue their studies and many who were in trouble in America. His bright future as a lawyer or politician ( his father was Judge of the First Instance in Ilocos Sur) tragically ended when that dreaded disease - leprosy unfortunately struck him in 1945. I often wondered what happened to him. He possessed a brilliant mind.

In January 1929, my brother Narciso was a senior at Stadium High school in Tacoma. Meanwhile brother Luis was in Hawaii working on a sugar cane plantation supporting his own family in great style as far as our barrio people could judge. He built a big house. During my 7th grade, Narciso and I had been corresponding. He told me the advantages of being in American school. He told me about American life and many wonderful things. He urged me to join him in the U.S. He wrote me and sent me $60 for my steerage passage to come to America. I was indeed in seventh heaven. I concentrated in my studies and when school ended in March 1929, I was again salutatorian. Attorney Ramon Crisologo was publicly recognized as my guardian, he stood and bowed to the applause of the audience in that elementary graduation.

I was in a dilemma. After my graduation, my dreams were all about America. The desire to remain as a schoolboy to Attorney Crisologo became repulsive all of a sudden. Narciso had won over Apo Ramon. Apo wanted me in Vigan, and was disappointed that he had not the honor to send me to Ateneo de Manila to be a lawyer. But my spirit was already in America. I pleaded that I wanted to go to America and join my brother. With sadness I wrote Uncle Andong that I was leaving Apo Ramon because I wanted to go to America. He came to see me in Vigan and I pleaded to see Mom so that she should let me join Narciso. Uncle said that I should accept Apo Ramon's charity and love and stay with him. I did not heed Uncle. So after a sad farewell to Marong and Icco, Apo Ramon sent me home to Narvacan with some pocket money and a new pair of shoes, shirt and pants.

I went home to Mom. My family was not happy to receive me from the care of such a benevolent master. I was reprimanded again and again by my mother. Why did I leave the good lawyer who had taken care of me for three happy years of my life. I shed many tears to convince Mom to let me go. She said that my brothers were far away and she missed them both. "Why should I let you go away also?" I pleaded with my sisters. They were all sympathetic, but they had no money to add to the $60 that Narciso sent me. Luis was married then, and so was Eugenia. So there was not enough steerage passage to Seattle. After many pleadings and tears, she reluctantly consented. Finally, mother agreed to mortgage the two pieces of land in order that I could go to America. She did this after receiving a letter from Narciso, that the mortgage will be paid in September 1929 when we got back from the Alaskan Canneries. I passed my doctor's physical. Mom mortgaged the fields for my ticket to the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Rufino goes to United States

I passed my doctor's physical and was very thankful and excited. Mom mortgaged one of the fields to one of the Pascua brothers who live in the barrio of Longong for my ticket to America. Before Narcis left three years earlier, the family gave him a farewell party. There was a lot of good things to eat, the wine flowed generously. When it was my turn to leave home there was no party but just prayers of petitions to Jesus for my good health and safekeeping.

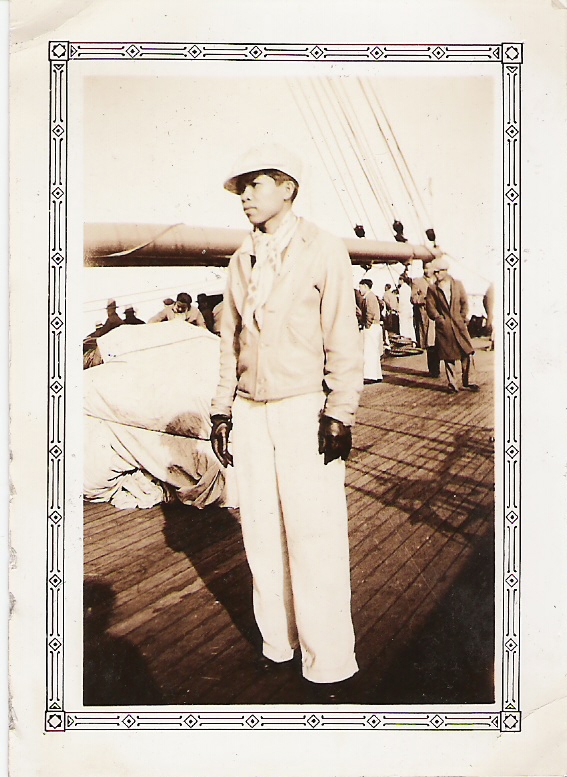

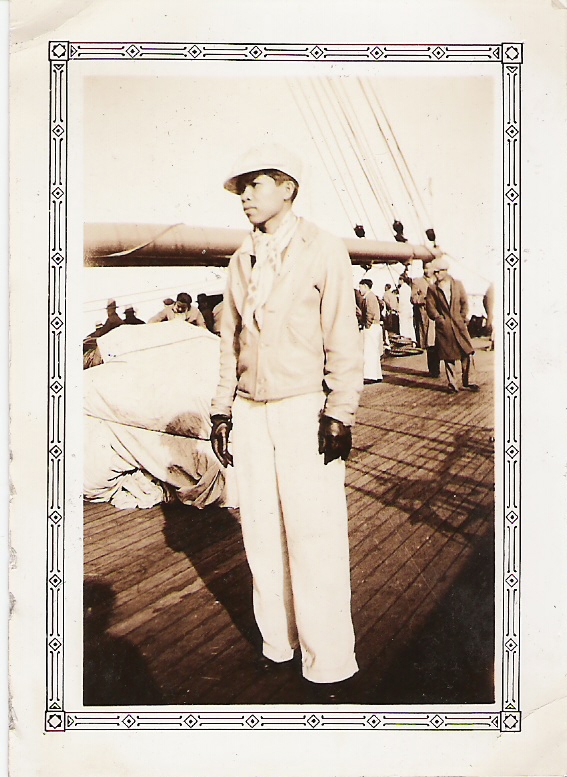

Thus Annong (Mariano) Atong (Donato Cabais) and Toning (Antonio Cabanig) and I took the pentram (bus) to Manila two days prior to the scheduled departure of the S.S. President Pierce from Manila to Shanghai, Tokyo and finally Seattle. This was the first bus ride in my life. The trip from Narvacan to Manila was dusty and there were even chickens being carried in baskets with a disgusting odor.

On April 23, 1929, we left Manila bay. We were cooped up in the ship's steerage hold in our bunks four tiers high. Everything went well with me until Tokyo, but after that acute seasickness overwhelmed me. Constantly, I vomited whenever the ship swayed carried by the big waves which often sprayed our area with sea water if one was slow to close a porthole. I lived only on orange juice provided by a kind member of the kitchen crew since I suffered more when I ate solid food. From Tokyo to Seattle, the passage was at times rough so we stayed in our canvas hammocks. But when the sea was calm, we swarmed like ants on deck to the surprise of the crew and the American first class passengers.

In my condition, I lost count of the days. I do remember that we left Manila on April 23, 1929 and landed weak but very thankful at 4:00 in the afternoon of May 20, 1929 in the port of Seattle where we were met by Flo.

Flo (Florentino Cabais) cousin of Atong came to the pier and met us. Atong was overjoyed to see his dear cousin remember our arrival as he had written him over a month before leaving Manila. Flo took us to Freedom hotel in a taxi. Toning and Atong had a room with a double bed while Annong and I had a similar room down the hall. Flo called us greenhorns and he delighted in showing us how to sleep between the white sheets, how to use the public toilet down the corridor. After setting us up in the hotel, he brought us to his place of employment where he showed us the menu - the list of things to eat. He ordered something for all of us - each having a plate. The supper was delicious and he paid for our meal.

Since it was Monday, we stayed in the hotel for five days until Narciso came to Seattle on the 25th to bring us to Tacoma. In our short stay in Seattle, Mariano and I did not venture too far from our hotel lest we would not find it when we wanted to return. Our other town mates who had relatives working in restaurants in Seattle fared better than Mariano and I. We ate meagerly since we had only $36 between us.

It was Saturday, May 25, 1929 at eleven when Narciso saw us at King and Maynard. He had not seen us for over three years. His first words were: "Nang aldao cayon?" (Did you eat lunch yet?) Narciso is not a sentimental fellow, he did not shake my hand nor embrace me. He told us that he is treating us to lunch. We were overjoyed. He ordered chicken for all of us. It was a Japanese restaurant where one of our town mates worked. After lunch, we went to our room in the hotel, packed our few belongings in our rattan suitcases. Annong and I left Toning and Atong and went to Tacoma with Manong.

Narciso put us in a taxi and we went to the Bus Terminal. We waited for the bus for Tacoma for a long time. This time the bus was clean and no chickens! We arrived at 5:30. From the bus station, we carried our bags for several blocks until we came to Market Street where 8 Pinoys were quartered in two bedrooms. Narciso arranged with Mr. Mariano Bolong, the house manager, that we would sleep on the rug in the living room. There I learned to use the telephone and was delighted whenever Manong called. We were to stay with Mr. Bolong until we went to Alaska, while Narciso continued his studies in order to graduate from Stadium High School. He was working for a rich family as a schoolboy to earn his board and lodging plus five dollars a month while going to school.

Port San Juan Cannery, Alaska 1929

We did not sleep too well on Saturday and Sunday nights for lack of blankets. On Monday, after school, Narciso brought us to a store and bought what we needed for Alaska, such as sheets and blankets and other items. We stayed with Mr. Bolong until we came to Seattle on Saturday, June 15th, when Narciso brought us back to Freedom Hotel waiting to be dispatched to Alaska. A few days after our arrival in Seattle, Mr. Herman de Cano called us to his office in King Street and signed us up for Port San Juan Cannery. Narciso, Mariano and I and many others left for Alaska on Saturday, June 22, 1929.

The old-timers enjoyed themselves with joyous laughter at the expense of the green horns. They played jokes on us like people do on April fool's day. Actually it is how each acted his part towards a greenhorn that is the hilarious act. It could not be told by words for if one does so, it seems silly and not even funny in the least. Hi-Q, dice, cards were the usual pastimes. Some would eventually lose and keep long faces while they thought of ways to regain their losses. In those free union times, we who went to Alaska for the first time believed that we were eating like kings comparing of course our meager meals in the islands. But the old-timers are a grumpy lot. They are never satisfied.

Except for the foreman, Mr. Herman de Cano, the Pinoys have nothing to say. The kitchen is run by Chinese cooks. Eat what is on the table or you starve. The Filipino Foremen were smart. The cook served good breakfasts. But lunch and dinner were monotonous. Fish today, tomorrow and the next lunch and dinner. I had no quarrel with balatong, beans or any vegetable, even fish. It was the old-timers that had the guts to complain every time fish was served.

The old-timers went to catch crabs whenever the weather permitted and the work in the cannery was finished for the day. Most times they also brought octopus with the crabs. Thus, the fare was a royal one whenever they arrived loaded with their precious catch.

In a fish salmon cannery, there are many classified jobs. Starting in the fishhouse: