That fall when I returned to Bayard, Dad was offered the opportunity of renting a farm. "Great," I thought, "I'll spend the remainder of my time at home on the farm." But the bank refused to lend Dad any money for equipment, so six months later he decided to return to Gilmore City and to his old job of hauling limestone. I was in seventh grade at the time. In some ways I hated to leave. I had just acquired a new girlfriend, a cute little farm girl with black hair and large brown eyes. Besides, life down on Willow Creek held many happy memories - the days spent playing Cowboy and Indian; the evenings outside on the grass catching fireflies or counting shooting stars; the holidays, especially the feast of St. Nicholas on December 6, when Dad would always shut off his car lights halfway down the lane, rap on the door, and leave a couple sacks of candy, nuts and fruit.

But move we did. It was late winter of 1952 when we again reached Gilmore City. For $25 dollars a month Grandpa Gehling rented us a house he had recently bought for $500. The house had four bedrooms, but was completely run down. There were holes in the ceiling, plaster falling off the walls, broken window panes, no carpeting, no bathroom, no sink in the kitchen. A ragged red tarpaper covered the exterior and a ramshackle porch hung precariously over the front door. The large yard was distinguished by a junkpile of cans and bottles (where we later dug our garden), a wood shed with no doors, and a privy that stank up the neighborhood. It took us several months to clean up the mess; in the meantime we survived as best we could.

St. John's Catholic School was just a block up the street, and all of us were soon back at our studies. I was ushered into the "big room," which contained the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. All three grades were taught by Sister Mary Joseph, a nun in her late fifties who had herself been born in Gilmore City. Sister Mary Joseph was a good teacher, sometimes a friend, always a counselor. The first day in school she pulled me aside to caution me about 'that troublemaker Hughie."

Hughie had been my old classmate in Kindergasrten. He and Jim were still at St. John's, though they had since been joined by several others - by a town boy named Jerry; by a lanky farm boy we called Clem; by very quiet sisters named Lucille and Eva; by Jeanette, an extremely tall farmer's daughter; and by the long-legged JoAnn. The nine of us would stay together until grade school graduation in late May of 1953.

There was one girl in the big room who immediately attracted my attenion. She was a petite, vivacious blonde named Patty. Though only in the sixth grade, she already knew how to conquer the male heart. Knowing of my infatuation, Uncle Albert and Aunt Lois allowed me to read some of their old love letters. From these I composed a love note, which I secretly slipped into the little blonde's homework. It was almost my undoing. Her Dad discovered the note and complained to the school. The next day Sister Mary Joseph took all the boys out into the hall one by one to question them about the note. I awaited my turn in a cold sweat, certain that I would eventually have to spill my guts. How could I possibly lie to a nun? As luck would have it, however, Sister Mary Joseph took one look at my innocent face and decided I was above suspicion. She never did take me out into the hall - and I, for my part, never did acknowledge the dastarlly deed to any of my classmates.

Living in town had its advantages. For the first time I had friends my own age to hang out with. First of all, there were Hughie and Jim, my old classmates from years before. Both had grown up. Hughie had developed a splendid physique - tall and muscular - but along the way had also acquired the reputation of a bad boy. He was always full of mischief and something of a bully, but hardly downright mean. He and I had many adventures together over the next few years and we always remained on friendly terms, even though we were never exceptionally close.

Jim and I, on the other hand, became like brothers. We were both about the same size, with the same interests and the same spirit of adventure. We worked the same after-school jobs. We played the same sports. We even chased after the same girls. Jim lived across town in a three-bedroom, frame house. His father was a plumber. He had a little sister who spied on us and a fat little dog who always tried to bite me.

Try as we might, Jim and I could not seem to stay out of trouble. My third week back at St. John's, he and I were caught looking up the word "intercourse" in the dictionary. In punishment Sister Mary Joseph rapped out knuckles sharply with her ruler and made us kneel for an hour on the ends of the desk runners. A few days later she caught us trying to depants a classmate on the school playground. For such a major offense she felt it necessary to call for a parent-teacher conference. Dad came home from the convent that night with a frown on his face. "Never been so embarrassed in my life," he grumbled. For a time thereafter I walked the straight and narrow.

Jim and I were soon joined in our boyish escapades by a sixth grader named Matt. Matt was a skinny little Irishman, with a face full of freckles and a tongue so steeped in blarney that he could talk his way out of nearly every situation. He lived with his grandmother and older sister in a big house on the south end of town. His mother had died a few years earlier and his father was off in Texas. He had one younger brother named Dennis, who stayed at the home of their uncle, Gilmore City's mayor.

Jim, Matt and I became inseparable. We passed notes in class, teased the girls mercilessly, and prowled the school grounds during recess looking for mischief. One warm spring day we decided to skip school altogether. Our plan was for Matt to go to St. John's and inform Sister Mary Joseph that Jim and I had taken sick. After a short time he was to complain of being sick himself. We would all meet at his place later to enjoy a day of freedom.

At first, all went according to plan. Jim and I arrived at Matt's drafty woodshack at precisely 9 A..M. with a bag of candy and an armful of comic books. We lolled around the woodshed for a couple of hours when, suddenly, we glimpsed through as crack in the siding, the awesome sight of my mother and Sister Mary Joseph striding down the street in our direction. Apparently Matt's golden tongue had for once failed him. He had confessed all. Jim and I were properly admonished and marched back to our desks, much to the amusement of our classmates.

Both Matt and Jim had after-school jobs as delivery boys at Hogan's Grocery. Since I already had a bike of my own I soon joined them. The work was not difficult. It consisted mainly of packing the customer's groceries into a box, balancing the box on the bike handlebars, and peddling through traffic to the proper house. We never knocked on arrival, but simply entered the back door and stacked the purchased goods on the kitchen table. We were paid five cents for each short trip, ten cents for anything over ten blocks. In a week's time we usually earned as much as $1.50-$2.00 apiece.

We soon came to know everybody in town. There was the hard-working Mrs. Jacobsen, who was invariably cooking dinner for her five girls when we arrived. There was Mrs. Campbell, who lived in a big white house near the highway. She always needed boxes of groceries to feed her growing boys. There was Mrs. Neil, whose huband ran the lumber yard. Before every holiday she would order several cases of Coke. It was quite a feat to balance the wooden cases on our handlebars without breaking a bottle, but she repaid our efforts with a generous tip at Christmastime.

Then there was Paul Sea - a portly, garrulous Irishman who lived in an apartment over the barber shop. Old Paul would usually be in the midst of a poker game when we brought his groceries. His room would smell of cigar smoke and unwashed bodies, and he himself would yell at us gruffly:"Put the groceries on the kitchen table and scram."

Hogan's Grocery was our home away from home. There we spent every day after school as well as Saturday mornings. When not delivering groceries we were expected to stock the shelves and take out the trash. Hogan himself was an elderly bald-headed Irishman, who chewed unlit cigars and drank strong black coffee. He sold groceries and vegetables only. If a customer desired meat he would send one of us next door to Dorensfield's Market. If someone wanted beer we were sent down the street to the local beer joint. The bartender grew so accustomed to seeing the three of us come in for a six-pack, that he thought nothing amiss when one day we decided to buy some for ourselves. We took the beer to an abandoned building and, after drinking a little of it, decided to serve the remainder to a stray cat we had found nearby. Just as we were beginning to pour some down the cat's gullet one of the local preachers happened by. He gave us a severe reprimand and confiscated the beer.

This taste for beer almost proved our undoing. In one of the houses to which we delivered groceries there was a large box of bottled beer. One day Matt, his brother Dennis and I waited for the homeowner to leave, then entered the back door and appropriated three of the bottles. We hid ourselves in a nearby stand of tall weeds, but were almost immediately pounced upon by an observant neighbor and the city marshall. They led us down to the mayor's office at City Hall and there detailed our crime. The mayor at the time happened to be Matt and Dennis' uncle. Uncle Mayor laid down the law that day. He forbade his two nephews ever to play together again, and threatened me with a stay in Boystown if I was brought to his office again.

I was thirteen years old when St. John's School opened for classes in late August of 1952. Sister Mary Joseph was again my teacher. Jim, Hughie and I were eighth graders, "the Lords of the School," or so we thought. Just as the school year started, a circus came to town. It was no Barnum & Bailey extravaganza, but it did have an elephant, a tiger or two, a lion, and a few performers. Hughie and I tried to get jobs raising the big top in exchange for free tickets. The roustabouts, however, decided we were too young and sent us away. We came back later that night, found a loose tent flap, and sneaked in to see the show. The next day we awoke to a rumor that the lion had escaped its cage. We gathered up a posse of boys on bicycles and rode the streets of town until dark. At any moment we expected to hear the beast's roar or feel its claws. We were not a little disappointed when word finally reached us that the lion was still safely behind bars.

Another rumor spread through town just before Halloween. Marshall Wolcott, it was said, had hired twenty deputies to guard the streets on the eve of All Souls. It was exactly the challenge we needed. Jim, Matt and I were too old for trick or treating, but we felt certain we could still accomplish our share of mischief. For some time we had been keeping an eye on an old outhouse near the north end of town. We tipped it over just as the Halloween sun was setting. Then, under cover of darkness, we made our way towards Goodrich's farm equipment storage area. While Matt stood watch, Jim and I drug plows and harrows and disks out into the middle of the street. We had no sooner emptied the lot then the first of the deputies arrived on the scene. He was soon joined by several others, all of whom cursed aloud as they began the process of clearing the street. We watched from the shadows for awhile - extemely pleased with ourselves - then crept off down the back alleys for the safety of home.

Winter came early to western Iowa that year. It snowed and sleeted and snowed some more. The streets froze over, and Jim, Matt and I had to abandon our bicycles and deliver groceries by sled. On our way to and from school we began to hitch rides on passing cars by grabbing the back bumpers and skiing along on our boots. Once in awhile a driver would stop to give us a tongue lashing, but by the time he opened his door we were usually down the street looking for another tow. When the Christmas holidays came, the big room decided to do some caroling. None of us boys had much of a singing voice, but it was a great opportunity to snuggle close to the girls as we moved through the cold from house to house.

One girl in particular caught my attention. Her name was Mary Ellen. She was in seventh grade. Her hair was dark, her disposition sunny, her conduct agreeably fiesty. As Valentine's Day approached I decided to make an all-out effort to spark her interest. At Mrs. Sinnet's Five and Dime I found a rack of expensive cards. Using half a week's wages I purchased the most expensive of all - a bit of romantic fluff picturing two skunks and a big valentine heart. The card did its work. Mary Ellen began calling me "stinky," and we soon became the hottest item around St. John's. We began spending recess time together, exchanging phone calls over the noon break, and walking home from school in each other's company.

The romance received a temporary setback in mid-March, after I found a small, portable pool table in the city dump At home that night I began using a razor blade to fashion a pool cue. The blade slipped, slashing a deep cut into my left wrist. I remember panicking as I looked down at the cut. Blood was gushing out. My whole hand had gone limp. Try as I might, I could not move my fingers. Dad and my sister Lois immediately rushed me downtown to the doctor's office. He was home eating dinner at the time. When he did finally arrive he could only bemoan the fact that my life blood had left a deep red stain on his beautiful linoleum floor. He set Lois to work mopping the floor, then applied a bandage to my wrist and a temporary tourniquet to my arm.

The tourniquet held until we reached Mercy Hospital in Fort Dodge. There the nurses forced a tube down my nose and throat, then wheeled me off to surgery, where a certain Dr. O'Brien used a series of long wires to retie the cut tendons that controlled the movement of my fingers. I was returned to my hospital room four hours later with a huge white cast completely covering my left arm. The next five days were the longest of my life. I lounged around the hospital, reading comic books by the tableful and waiting impatiently for the arrival of visiting hours. The third day there, Sister Mary Joseph showed up with an armful of letters from my classmates. She had been accompanied to the hospital by my friends Jim and Matt, but both had been denied entrance because of their ages. Before the evening was over, however, they managed to sneak past the hospital staff to spend a little time in my room commiserating over my plight.

I returned to St. John's a minor hero. Everyone signed my cast. The girls felt especially sorry for me and walked me to and from school to keep me from falling in the snow. I enjoyed the attention immensely. After six weeks of preying on their sympathy, I was returned to Dr. O'Brien's office to have the cast removed. He cut it off completely, exposing two rows of metal beads, one row just below the wrist, the other on my upper arm near the elbow. The beads were attached to nine long wires that wound around each of my tendons. "Now this will hurt some," the doctor cautioned as he snipped off a bead and began tugging on the first of the wires. And hurt it did. I yelled and howled and screamed each time he pulled out one of the wires. Dad helped hold me down, but I noticed that when the ordeal was over he too had tears in his eyes.

After the cast was removed my life began to change. The school year quickly drew to a close. The nine of us in eighth grade graduated on 20 May 1953. I went back to work at Hogan's Grocery for the summer Jim was no longer there. Some time earlier a boyish escapade had landed him in the hospital, and soon after his parents had insisted he quit delivering groceries. Matt and I continued on, but realized that we had forever lost the third in our triumvirate.

The three of us had some months earlier made a pact to go away to school together. The idea had come from a pamphlet presented to us by Sister Mary Joseph. It told the story of Divine Heart Seminary in Donaldson, Indiana, where young boys were trained for the Catholic priesthood. The pamphlet had been written by a certain Father George. Tucked inside was a card to be returned. I filled out the card and sent it off. Jim and Matt hesitated for a time, then finally decided they weren't quite ready to leave their homes.

A few weeks later I received a long letter from Father George. He would be in the area in July. "Would I care to see him?" I had never considered myself very religious, but the idea of going away to school - for whatever reason - appealed to me. I marked in my "yes," and a month later Father George pulled into the driveway. He had first stopped off at the parish rectory to check into my character, which was charitably reported as "deserving." That evening Father George showed my family and me some slides of the seminary, assured my parents that the tuition fees could easily be waived, and signed me up for the fall semester.

The remainder of the summer was spent in filling out my wardrobe (which originally consisted of a couple pair of pants, one pair of sneakers, and a few well-worn shirts}. In late early September, Sister Mary Joseph invited me back to St. John's for a going-away party. Most of my friends had, of course, already graduated. But Matt was still there, and it was he who met me at the front door. A couple of my old girlfriends were also still there. They had brought in a phonograph and a few of the latest records, including everybody's favorite - "How Much is that Doggie in the Window?" Although one girl batted her eyelashes at me a few times, all seemed perfectly content to give me up to the celibacy of the priesthood. Sister Mary Joseph was all smiles and encouragement. One of her graduates had finally decided to follow her into the religious life. She expressed the hope that more would follow.

For me the party signalled the end of my carefree boyhood days. I would never again live with my family in Gilmore City, except for the Christmas holidays and summer vacations. My old friends would grow up without me, go on to high school, marry, and begin their careers. Only in later life would I find out what became of them.

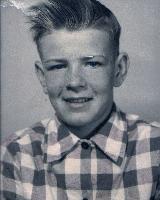

Hughie would move to Fort Dodge, Iowa, settle down, have a family, and reportedly become a loving and caring father. Matt would go to Texas to be with his Dad. He would later join the Texas State Patrol and be gunned down while ticketing a car with Iowa license plates. Jim would migrate first to Boone, Iowa, later to college in California, and to a successful career in the aerospace industry. And as for that little farm boy named Dickie - well, he would go on to high school in northern Indiana and to a new and completely different life far from his roots in western Iowa.

©1999-2005 Richard Gehling

E-mail me.