Page 3

DOC

The Biography of Edgar

Derry TILLYER

However, no sooner had the family settled into their

Southbridge home and Edgar had his laboratory up and running when

the United States entered World War I. Edgar's challenge had to

wait while the AO changed direction and entered the war effort.

It did not take long for Edgar's team to get recognized for their

work. During this war, the 37-millimeter telescope sight for the

tank repelling guns had been made by France and required a barium

crown glass which was available only in France.89

90 This was the best available equipment at the time,

but the source was unpredictable and liable to disappear under

German attack at any time. The American government pressed the

optical manufactures in this country, such as the AO, to design

an equivalent sight. The response from these companies was always

the same. "We don't have the type of glass we need,"

they would all reply.

When Edgar heard of the problem, his mind went to work and

soon he had redesigned a gun sight so that it could be massed

produced with domestically produced ophthalmic glass. The

finished product was so impressive that the French government and

their military forces admitted it was better than theirs.91 Edgar also developed a basic redesign

of the machine gun telescopic sights which were rapidly adopted

by the military.92

As the World War I effort intensified, the AO's war effort

intensified as well. In 1917, the AO furnished the military with

two and one-half million lenses for the troops.93

Edgar continued to make important contributions. One of these

contributions was the development of a bomb site for airplanes

that was much more accurate than the method they were using at

the time.94

Edgar's private life continued, also. In 1919, Edgar's father

Lorenzo TILLYER developed kidney cancer. The local doctors

suggested that he be evaluated by the specialists in Boston. The

Boston doctors examined Lorenzo and told him that his disease was

very serious and was incurable. Rather than return directly to

New Jersey, Lorenzo went to Southbridge where he broke the news

to the family. This greatly upset and depressed Edgar who seemed

to personalize this and was sure that he to would develop cancer.

It was also during this visit that Lorenzo told his

daughter-in-law, Florence, in the presence of the children, that

he felt that Edgar's treatment of her was not right. It was so

bad that he said he wanted to rewrite his will so that both

Rozena and Edgar would be cut out of any inheritance. He said

that he wanted to leave his money entirely to Florence.

Although the money wasn't much, Florence pleaded for him not

to do that. She knew that Rozena would fight that will and would

win. "The money would go to Rozena first and that would make

things even worse," she cried.

Lorenzo eventually agreed but set up his will so that the

money would go first to his wife, Rozena, to have during her

life. He added a provision that required one thousand dollars

would go to each grandson, Richard, Edgar William, and Lynd, to

be used for higher education and another thousand was to be given

to each boy when they reached twenty-one. Louise received five

hundred dollars for higher education and one thousand when she

became twenty-one. Lorenzo's son, Edgar would receive the

interest on all the money that was left over.95

Florence's headaches continued to increase in frequency and

intensity.

Also in 1919, Lynd Francis, their fourth child, was born on

August 2.

Bill started school in that year also. For the first few years

Bill had trouble writing, insisting on writing everything

backward. His wrists were consistently being slapped by Mrs.

Buckley, his teacher, because he was writing with his left hand.

This constant punishment and frustration at school caused Bill to

skip school and to play in the woods. Soon Edgar and Florence

were called into the school office for a conference with Mrs.

Buckley, the teacher, and a second Mrs. Buckley who was the

teacher's sister and the school probation officer. When Edgar

discovered that the problems stemmed from the boy's writing

problem, he stood up and said in an exasperated tone, "Just

let the boy write with his left hand, for heaven sake!" and

pulled Florence out of the conference.96

In

March 1920, Edgar began spending more time in Dover to be with

his father who was becoming increasingly weaker with his kidney

cancer. Rozena wrote that this time that Edgar spent with Lorenzo

"gave them both great joy." On 30 July 1920, Lorenzo

died or as Rozena describes it, he "crossed to the Home

where the dear babies were awaiting him." Lorenzo was buried

in the family plot of D.A. DERRY in Orchard Street Cemetery, in

Dover. This plot was purchased by Daniel DERRY to be used by his

own family and their families.97

In

March 1920, Edgar began spending more time in Dover to be with

his father who was becoming increasingly weaker with his kidney

cancer. Rozena wrote that this time that Edgar spent with Lorenzo

"gave them both great joy." On 30 July 1920, Lorenzo

died or as Rozena describes it, he "crossed to the Home

where the dear babies were awaiting him." Lorenzo was buried

in the family plot of D.A. DERRY in Orchard Street Cemetery, in

Dover. This plot was purchased by Daniel DERRY to be used by his

own family and their families.97

Orchard Street

Cemetary Dover, NJ

Soon the war was over and the frantic pace of the war effort

slowed, so the AO was able to return to civilian activities. In

1921, Edgar put the final touches on another invention that

allowed the first measurement to effective lens power.98 This invention was an instrument

known as a Lensometer. This machine fulfilled the long sought

practical and accurate method to detect whether the eyeglass lens

had been ground to the precise prescription called for by the eye

examination.

The question optometrists and opticians had always asked was

"how do we know the lens is accurate and exactly fills my

prescription? It is so easy to make a slight error which cannot

be detected with what we have now?"

The Lensometer was a mechanical eye with a separate and

movable light bulb (which was termed the "target"). The

machine received light exactly as the eye does except backwards.

Instead of the light coming through the lens of eye and landing

on the retina at the back of the eye, the light starts at the

"retina" and shines out through the lens. In this

machine, the light comes from the target which is the light bulb

and radiates up through a telescope-like tube to the lens at that

end of the tube. By putting the eye glass lens at the end of the

tube, these light rays reached the examiner in the exact way they

would reach the eyes of the patient. The light ray deflections

were recorded and were easily compared to the prescription and

the accuracy to the lens was immediately determined. "This

machine had been needed for as long as lenses had been ground and

at the time was considered one of the greatest inventions in

ophthalmic science. All the instrument lacks to make it a real

human eye is an optic nerve and a mind."99

Another helpful feature of this machine was that it could be

used to measure fragments of broken lenses to make replacements

quicker and easier.100

Another of Edgar TILLYER's inventions made about this time was

a means to apply invisible markings to lenses which only became

visible when someone blew their moist breath on them.101

In the early 1920's, Edgar developed an interest in

ultraviolet and infrared light, the invisible portions of the

light spectrum. Edgar described this interest in 1941. He wrote

that our eyes are "sufficient to adapt to ordinary

intensities" of light. However, the increase in outdoor

activities and increase in the industrial use of high intensity

light is causing a "problem of adequate protection against

excessive visible and invisible rays."

In 1924, after years of research, Edgar was able to

"blend in careful balance ferrous and ferric iron

ingredients and other oxides" to produce an olive green lens

with both high ultraviolet and infrared absorption.

This new glass was called Calobar102 and

was immediately used in industry to protect against

"radiation which causes tired and irritated eyes." It

was later used by the United States Air Corp. to solve the

problem of aviator headaches and eyestrain.103

The AO in a brochure described Doc's basic concept and

development of ultraviolet and infrared ray absorptive lens with

selective high visible light transmission was the first effective

approach to high quality sunglasses. The new Calobar lenses,

became the standard for the Army and Navy prior to World War II.104

It was at this point in Edgar Derry TILLYER's life that he was

becoming aware that he was famous and an important person. He was

receiving visits from government officials and receiving praise

and accolades from the media. However, when asked by the Rutgers

Alumni Association to provide some biographical material, Edgar

wrote back, "Helped the Navy get good submarine periscopes;

wrote their specifications during transitions from poor to good

ones. Wrote many naval gun sight specifications. Designed some

gun sights. Have a few dozen patents in the optical art. Nothing

of much importance."105

Edgar tried to be a father to his children. He had a sand box

and swings built in the back yard and he would take his family to

the railroad station as the troops were passing through

Southbridge or Worcester and they wave flags and cheer them on.106 He never helped Floss with the

children or their household activities or homework, however. 107

The household was run by the clock. Floss awakened the

children and fed them their breakfast. The children's breakfast

was cereal, toast, prunes, milk and an occasional egg. Florence

would preach the benefits of hot cereals such as oatmeal. Edgar

would have a heavier breakfast consisting of fruit, meat (his

favorite was two eggs on hash), cereal, toast and coffee. At noon

they had their main meal which was usually was meat, potatoes,

vegetable and a dessert. At the sound of the AO noon whistle, all

the children came home from school to eat and Edgar came home

from the plant. The AO had a loud whistle that echoed throughout

town telling all that it was time to start work, time to break

for lunch and time to get back to work and finally time to quit

for the day.

Supper was always at 6:00 P.M. After the supper, Edgar would

lay down for a brief nap then he'd do things like build radios,

study journals or read the newspaper. After a few hours of

reading, Edgar would pull out his mechanical pencil and go to

work on the problem of the day. He would sketch and formulate

equations while sitting in his old stuffed chair in the living

room well into the night. The children, of course, gave him

wide-berth when he was doing his work; they didn't understand

much of what he was doing anyway. Edgar always sat in his chair

with his feet on the foot stool. He seemed to be perpetually

doodling when actually he was brainstorming some new project.108

Edgar believed that a woman should always think and do as her

husband did and be beaten if she didn't. This, of course, was not

how Floss was brought up. Things were getting more intolerable

for Florence. "Teddie ROOSEVELT treated his horses better

than you treat me," she'd sob but Edgar would just walk

away.109

While Floss took part in as many civic activities as Edgar

would allow her to attend, he thought these duties were trivial

and never participated in them himself. Edgar became ever more

suspicious of his wife's time out of the house and when she went

to women's club meetings or similar meetings he accused her of

meeting another man. This jealousy and physical abuse continued

and Florence continued to try to ask him for a divorce. At one

point he boasted, "You'll never leave me. Go ahead, try. If

you leave, you'll never see the children and I'll give all my

secrets to the Germans."110 Florence,

of course, never did leave.

Edgar had a natural affinity for mechanical devices new and

innovative. He felt comfortable and confident with his ease at

understanding the new concepts and fresh ideas. At this time the

automobile was still a new and adventurous machine. As such,

these were important to Edgar. Buicks were his choice of vehicles

and it had to be the biggest model available.

When the children were young, he'd buy the Buick touring model

with open sides. When it rained, Edgar would have to stop

(usually in the middle of the road) and put up the Isinglass

windows or the passengers would get wet. If they were only a few

miles from home, however, Edgar considered it a waste of time to

stop so sometimes the family would arrive at Maple Street soaked

through to the skin.111 Every

Sunday the TILLYER family would take a drive into the country.

This would be a "silent" drive because the children

were not allowed to make any noise and Florence was not allowed

to talk during the drive.112

Edgar's Buick's always had the latest gadgets. He was proud of

these and did allow conversation if it involved showing and

explaining these accessories and toys.113

One evening as the family was eating their supper, Bill looked

out the window at the "Hupmobile" owned by Mr. Watson,

the next door neighbor. Bill noticed what appeared to be a fire

under the car. "Pop, why does Mr. Watson's auto have a fire

under it?" It was an innocent question. Automobiles where

still mysterious to the children then and perhaps they were

supposed to have a fire under them. Edgar leaped from his chair

and raced out of the house shouting, "Watson, get out

here!" Together they managed to get the fire out without

much more commotion.114 Generally,

however, Edgar was aloof from his neighbors and showed little

interest in them.115 This

detachment from the neighbors even applied to the BOYLES family

living next door to him on the railroad side. Their son, John,

became a famous movie star in Hollywood in the early years.116

Back in the research laboratory in 1926 a momentous event was

about to occur. After years of work and a huge safe full of fat

ledgers loaded with computations, the 46-year-old Edgar TILLYER

finally completed the lens that the AO so desperately had been

searching for.117 First, Edgar had

developed the TILLYER Principle which established the basic

principle for a corrected curve lens in 1917. Then with his

assistants in his research laboratory, he spent the next nine

years translating this principle into a complete series of lenses

for the eyeglass industry that corrected practically every type

of visual defect.118 Finally, in

1926, Edgar TILLYER patented a series of lenses that controlled

"off-axis power and astigmatism errors" which were to

become the TILLYER Lens.119

What Edgar Derry TILLYER and the AO Research staff had done

was to produce a corrected curved lens that would improve the

optics of the conventional six base lenses. Edgar TILLYER

conceived a "step" system that used a limited range of

selected base curves. Each base curve was calculated in steps so

that just before off-axis errors approached a level that could

adversely affect the patient's vision, the next base curve would

take over. This discovery allowed the AO to provide a practical

way to eliminate off-axis visual errors.120

In recognition of his accomplishment, the lens was called the

"WELLSWORTH - TILLYER Lens."121

No ophthalmic lenses had ever received so much study, research,

and subsequent praise.122 His new

basic principle created marginal corrections which were as

accurate as the correction in the center of the lens for the

first time in history.

One AO promotional publication stated that the application of

the meticulously formulated TILLYER Principle to create the

TILLYER Lens was one of the greatest developments in the progress

of optical science. This offered the best solution to correct

both spherical and cylindrical errors at the lens margin. Until

that point lenses could correct one error but not both.123 (Note: spherical corrections are

used for problems in distance and close vision; cylindrical

corrections are used with astigmatic problems).

"I do believe that this has given me more satisfaction

that anything else," Edgar said about his world famous lens.124

It was at this time that the name "WELLSWORTH" was

officially dropped from the lens and it became the "TILLYER

Lens."

The AO created a division of the company called The TILLYER

Lens Company. Its function was to promote and sell the TILLYER

Lens. As part of that effort, the TILLYER Lens was announced in a

full page ad in the December 1929 issue of the Saturday Evening

Post magazine. The company commissioned the painter, Norman

ROCKWELL, to create this advertisement. He painted himself as a

young man wearing eyeglasses. ROCKWELL's picture shows ROCKWELL

as a teenage boy at this bedroom desk wearing eyeglasses and

working on a wooden airplane model. There is a small dog sleeping

at his feet. The text asks if his eyes are having as much fun as

he is then goes on to describe the new TILLYER lens as the most

comfortable lens available. 125

Edgar said, when asked about his feelings when he was asked to

develop this lens way back in 1916, "I knew less about

ophthalmic lenses at the time than anything else." 126

Another selling point for the superior quality of the TILLYER

lens was that fact that it was polished with a newly created

process that used "non-elastic polish."127

Edgar's influence was felt strongly on the AO since he had

arrived in 1916. However, as it was pointed out by one of Edgar's

co-worker's, even though Edgar was hired in 1916, his effect on

the AO had been felt well before he arrived. In the metrology 128 laboratory, there was a set of

highly valued master lenses which had been calibrated at the

National Bureau of Standards. This set of lenses had an NBS

Certification of Calibration that bore the date "February

11, 1916" and the familiar initials "EDT". These

master lenses were used to calibrate lens curvatures. They

themselves had been measured by Edgar while he was at the

National Bureau of Standards. So any optical surface which had

been calibrated against these standards could be certified as

having an accuracy traceable to the Bureau of Standards. In the

ophthalmic world, these lenses were unique to the AO in the

1980's. No other ophthalmic optical company had such traceablilty

to the Bureau. Edgar's influence on the AO had indeed started

before he arrived.129

About this time Edgar took up the hobby of photography. Edgar

had a cottage at a nearby lake. He'd often take his motor boat or

canoe out by himself and take pictures of the sunset or the ducks

or the surrounding trees. He enjoyed this time to relax and enjoy

the quiet and solitude that this photography gave to him.130 He often spoke at an amateur

photographer's club at the "technical" high school

(Trade School) in Southbridge. He also spoke about optics and

astronomy to these classes. Students reported that when Dr.

TILLYER spoke his enthusiasm about his subjects was so contagious

that he inspired them to go into the optical profession. 131

He also became interested in begonias and day lilies. The

small backyard on Maple Street gently sloped down to the house.

This was Edgar's garden where he grew these flowers in the

summer. He used the greenhouse built on the side of the house to

continue his horticultural work in the winter. One of his

interests with these plants was his desire to develop various

strains and crosses. However, when he was asked about his ability

to make these plants prosper and reproduce he said irritably,

"I don't breed them. They're hard enough to grow without

worrying about breeding them."132

Edgar often brought spectacular begonias into the office; the

beautiful blossoms were enjoyed by all those in the Research

Laboratory.133

His interest in the nature and botany did not extend to

regular yard work, however, and he made his sons maintain the

yard. Edgar required his wife to do the housework and maintain

the household. He gave her an allowance to do that. He, however,

paid for the gas and electricity and other utilities by sending

them a rather large check and telling the utility companies to

notify him when they needed another check. Edgar would have

nothing to do with the monthly bill and payment routine.

Religion was not important to Edgar and he would have nothing

to do with that either. It was important to his wife though and

Florence saw to it that all the children regularly attended

Sunday School. A few times a year Edgar would relent and allow

Florence to attend church herself.

Edgar enjoyed tennis and badminton. There was an unwritten

rule that Edgar was to win these games and the last time that he

played tennis was the time that his oldest son, Richard, beat

him. He lost interest in the game after losing to his son.134 However, he did admit his game was

not what it had been.135 When the

children were older, the family enjoyed playing bridge.136 Doc also developed a new system to

use in bridge strategy which, unfortunately, was not infallible.137

In 1926, Edgar bought a used Model "T" Ford for Dick

to use for transportation back and forth to Rutgers in New

Jersey. Louise was in her last year of high school at the time

was allowed to use it before Dick came home to pick it up. Edgar

drove the Ford home and parked it in front of the house telling

Louise, "you have to shift with your feet." Louise knew

nothing about this strange method of shifting since she learned

to drive using the standard shift type car. She was left to learn

how to drive this car by herself. For the first few months she

had such a difficult time shifting into reverse she always parked

it so that she would not have to back up. She, Bill and Bill's

friends all had a great time and a big laugh at her attempts to

drive that car. 138 139

Eventually Edgar sent all his sons to Rutgers and sent Louise

to Douglass, the woman's college adjacent to Rutgers and

considered the sister school to Rutgers. He insisted that his

children attend Rutgers to prove that he was in fact a success.

Family stories say that in Edgar's college yearbook one of his

peers had written that he, Edgar, should be chosen as "the

person least likely to succeed."140

Incidently, Bill was involved in a serious automobile accident

on his way to his first semester at Rutgers. One person was

killed and another injured in the collision. The injured person

sued Bill. Bill missed the first semester of that year because of

his injuries and lawyer visits.141

The community, when they read newspaper accounts of the accident

said they felt that Bill would "get out of it" because

of the importance of the TILLYER name at that time.

It was about this time in the history of the TILLYER family

that Bill became fully aware of the domestic problems at home. On

several occasions Bill would argue and fight with Edgar about

Edgar's treatment of Bill's mother. Several times Bill would be

in tears of anger and shout at his father, "If you hit Mama

again, I'll hit you!"142

This, of course, was a very private era where people did not mind

the business of others especially the business of a very

unapproachable and famous person as Edgar. He

"specialized" in inflicting bruises on his wife in

"non-public areas," areas that were easily covered by

clothing.143

In the office, things could be difficult at times, also.

Esther BARNES came to work for Edgar as his secretary in 1926.

For the first six months Esther said that she "was sorry to

make the change. Doc was very temperamental and difficult to work

for," she said diplomatically.

"I almost quit several times," Esther continued.

"One day, first thing in the morning, I had a call from

Norman PRICE [one of the AO's executive officers] requesting that

I make Doc answer a letter from him which should have been

answered three weeks before."

Norman PRICE told her to tell Edgar that it must be answered

that day. Esther looked up when Edgar walked into the office that

morning and said, "Doc, the first thing I want you to do is

answer a letter sent to you by Norman PRICE three weeks

ago."

Edgar flew into a rage, shouting, "No secretary of mine

is going to tell me what to do!" He grabbed a pile of papers

on her desk and threw them all over the floor.

Esther became just as angry and concerned for her safety. She

grabbed her coat and purse and stormed out of the office. Papers

swirled and fluttered behind her. She went directly home to be

comforted and encouraged by her parents. They were able to

convince her to return and at one o'clock that afternoon she

hesitantly and fearfully returned to her job. As she edged back

into the office, Esther noticed that the papers had been cleared

from the floor and everything else had been returned to order.

Edgar walked back into the office about fifteen minutes after

she arrived. "Hello, Esther," he said pleasantly.

"I want to talk to you." He placed his fedora hat on a

chair and removed his gray suit coat. He stood in front of her

for a minute as he thought of the correct words to use. He was

dressed in his dull gray vest and long sleeved white shirt. Then

strode over and hopped up on her desk. He squatted down, looking

straight into Esther's confused and fearful eyes.144

Later Esther said, "Doc actually did squat on the desk. He

came over, swept the papers off the desk and climbed right on up

and squatted in front of me."145

After a moment of silence, Doc said, "I have been looking

at new Buicks. I want to take you up to the agency and get a

first-class opinion."

The astonished secretary stammered, "Sure."

Together, they went up to the Buick dealer in Southbridge. She

said "yes" she did like the car that Edgar wondered

about and suggested he go ahead buy it. He took her suggestion

and bought the new Buick. Esther said that things went pretty

well after that and that experience allowed them both to

understand each other better.146

She worked for Doc for the next ten years as his secretary and

she never said that she wondered whether Florence would like the

Buick.

In March of 1928, Edgar TILLYER visited Rutgers probably to

arrange for the June ceremonies when he would be awarded a

doctorate. While there he inspected VAN DYKE Hall, the new

physics building on campus. There is no indication of his

impression of the building.147

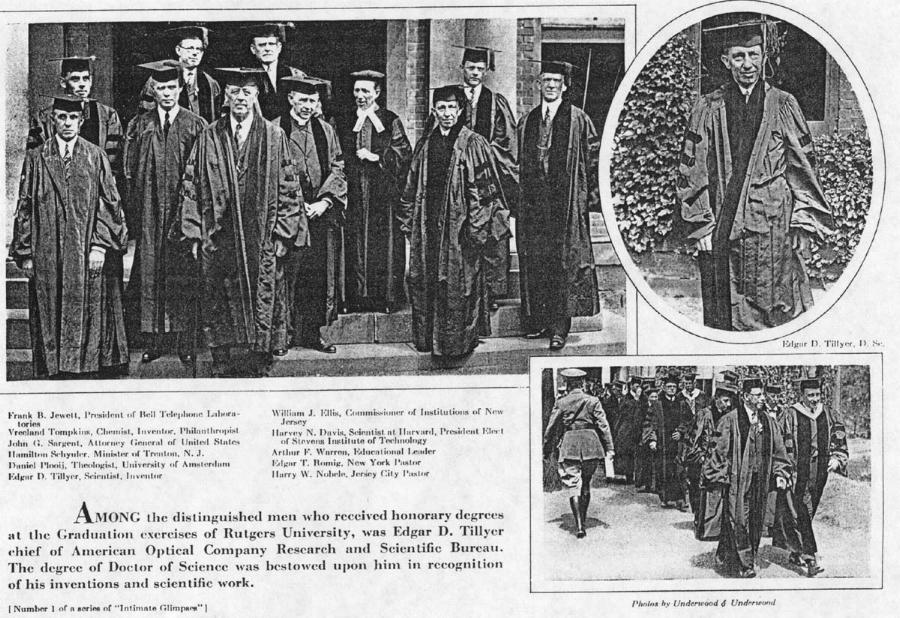

In June 1928, Edgar returned to the Rutgers

campus to receive an honorary Doctor of Science degree as part of

the one hundred and sixty-second commencement ceremonies at the

school. Edgar was called up to the dais and the presenter spoke

these words, "Edgar Derry TILLYER, being honored for

scientific achievements in the Naval Observatory and Bureau of

Standards of the United States.

Doc gets honorary

degree

"Distinguished for notable service to his country during

the great war by improvement of the telescopic gun sights.

"Invented the TILLYER lens and author of the standard

periscope specifications for the United States Navy

"Director of one of the leading research laboratories in

the United States in the field of optics.

"Your Alma Mater, recognizing you as one who has brought

distinction to its instructions in physical and mathematical

sciences, confers upon you the degree of Doctor of Science."148

When he returned to Southbridge, his staff and co-workers

started to call Edgar "Doc." This nickname seemed to

fit the man and became his name for the rest of his life although

he never used this title or signed any of his papers or articles

using any reference to "doctor."

Doc's mother, Rozena, died on 9 November 1928, at her home in

Hightstown. Doc returned to Dover to participate in her burial

ceremony. She was buried in the DERRY family plot in the Orchard

Street Cemetery next to her husband.149

Four months later, on 16 March 1929, Florence's father,

William LaRue LYND, died in Dover and was buried in the Locust

Hill Cemetery in Dover.150 When he

died at the age of 72, the whole town observed his funeral. The

schools, factories and businesses closed in respect of this man.

His thoughtfulness and care put the Richardson and Boynton

factory back to a working basis relatively quickly after the 1914

fire allowing the hundreds of idle employees to return to work.151

Doc probably felt true shock and sorrow at this loss because

he seemed to respect his father-in-law. This was uncommon for Doc

to respect a "non-scientist." He usually ignored people

who could not understand math or physics but every summer Doc

would bring his family to New Jersey to visit the LYND'S. The

children loved to be around their Nana and Grandpa and had a

wonderful time there. Doc never lost his composure or became

impatient or angry while he was visiting them.152

153

Next

Page

Previous

Page

End Notes

Bibliography

Please contact me with any

comments, additions, corrections or anything else involved

with Doc's biography.

We hope that you find this

useful and interesting

Tim TILLYER

jtillyer@sdcoe.k12.ca.us

In

March 1920, Edgar began spending more time in Dover to be with

his father who was becoming increasingly weaker with his kidney

cancer. Rozena wrote that this time that Edgar spent with Lorenzo

"gave them both great joy." On 30 July 1920, Lorenzo

died or as Rozena describes it, he "crossed to the Home

where the dear babies were awaiting him." Lorenzo was buried

in the family plot of D.A. DERRY in Orchard Street Cemetery, in

Dover. This plot was purchased by Daniel DERRY to be used by his

own family and their families.97

In

March 1920, Edgar began spending more time in Dover to be with

his father who was becoming increasingly weaker with his kidney

cancer. Rozena wrote that this time that Edgar spent with Lorenzo

"gave them both great joy." On 30 July 1920, Lorenzo

died or as Rozena describes it, he "crossed to the Home

where the dear babies were awaiting him." Lorenzo was buried

in the family plot of D.A. DERRY in Orchard Street Cemetery, in

Dover. This plot was purchased by Daniel DERRY to be used by his

own family and their families.97