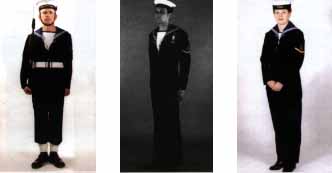

Royal Navy Ratings

Some Royal Navy cap tallies in my collection

Patch of Women's Royal Naval Service Medical Officer

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm doth bind the restless wave,

Who bidd'st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep:

O hear us when cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea.

The winds and waves submissive heard,

Who walkedst on the foaming deep,

And calm amid its rage didst sleep:

O hear us when cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea.

Upon the chaos dark and rude,

Who bad'st its angry tumult cease,

And gavest light and life and peace:

O hear us when cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea.

Our brethren shield in danger's hour;

From rock and tempest, fire and foe,

Protect them wheresoe'er they go:

O hear us when cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea.

O Saviour, whose almighty word

O sacred Spirit, who didst brood

O Trinity of love and power,

LEST WE FORGET

Royal Navy History

Introduction

At the close of the twentieth century, the Royal Navy probably has a less clear public profile than at any time for three hundred years. The reasons are easy to determine. National Service is a distant memory for most people, so few have experienced the Royal Navy at first hand. The Fleet itself is smaller than at any time since the start of the Napoleonic Wars. Even its most recent successful campaigns, in the Falklands, the Gulf War and the humanitarian efforts in the former Republic of Yugoslavia, became history as soon as the television cameras departed.

The "Silent Service", however, owes much to its heritage. Whilst the past and its associated traditions should not determine the future, they offer a good guide to how the Royal Navy of today came into being. The next few pages, therefore, offer an introduction to our Naval history. It is a record that is inextricably linked with the development of the nation. For centuries, in this island power, the wealth, prosperity

and independence of the people chiefly depended on the security offered by the sea.

A Short History of the Royal Navy

Sea power has helped shape history since ancient times. Organised naval forces first made an appearance in the Mediterranean, where over the course of centuries Egypt, Phoenicia, Persia, Greece, and Carthage maintained navies. The laws of the sea that were adopted in those distant times can still be traced in today's modern Navies.

The earliest warships were galleys, vessels propelled by banks of oars supplemented by sail. The principal weapon with which they were equipped was a pointed beak, or ram, used to pierce the side of an enemy vessel. This was supplemented by archers and swordsmen who attempted to capture an enemy vessel by boarding it. Although the galley was usually confined to protected waters, the Vikings used oared longships to swoop down on unwary targets along the Atlantic coast of Europe.

The early Kings of England realised that to maintain control of the sea required some form of Navy. Often, however, they neither had the money nor the resources to build a fleet. In its absence, Caesar, the Danes and the Vikings were able to attack these shores. King Alfred (who reigned from 849 to 899) is the earliest monarch whom we know was able to construct a Fleet. A chronicle records him ordering ships to be built, with banks of oars as well as sails, to meet the Danes in naval battle.

His triumphs, however, were short-lived. Invaders descended as the prototype Navy withered away. Thus when Harold faced William the Conqueror in 1066, there was no fleet capable of intercepting the Norman invaders on their way to Hastings. It was a mistake that lost a dynasty a kingdom.

The age of exploration and nationalism that began in the 15th century coincided with the development of larger and handier sailing ships. With the invention of gunpowder and the deployment of light guns to sea, naval warfare took a new course. Equally, increasing awareness of the stars and the perfection of navigational instruments enabled sailors to venture out of sight of land. With full awareness of the potential this offered Henry VII ordered the first Naval dockyard to be built at Portsmouth. His son, Henry VIII founded a fleet of sail-driven battleships,

with heavy guns along their sides below deck. The greatest of these was 'Henry Grace a Dieu' and she carried guns from a new foundry that produced the best muzzle loading weapons in the world.

The discovery of sea routes to India, China, and the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries led to a growing volume of trade, and national rivalries for control of these routes created the need for navies. Until the end of the 18th century, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, France, and Great Britain were almost permanently engaged in maritime wars to win mastery of the seas and control of the vital trade routes that linked their overseas colonies to the parent country.

Great sea struggles ensued, such as the campaign surrounding the Spanish Armada. In 1588, one of the great invasion fleets the world has ever seen, was destroyed by a combination of the tactics of Sir Francis Drake, the power of English gunnery and the often violent vagaries of the weather. Queen Elizabeth's Protestant realm survived through control of the seas. It was a lesson that few of her successors were to forget.

The next great challenge came as Napoleon rose to rule Europe. In the wars and campaigns that engulfed the great Western nations between 1792 and 1815 the Royal Navy employed hundreds of ships and craft to blockade and destroy the enemy. The greatest victories in battle were those involving ships commanded by Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson. His fleet of 'far distant, storm-beaten ships' were all that stood between the French Grand Army and domination of the world.

In a series of great and bloody naval battles, Nelson played a decisive role in defeating fleets belonging to France and her allies. Napoleon was unable to lift the blockade of his forces and the Grand Army was prevented from invading England. In the epitome of conflict at sea, the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October

1805), Nelson died as his ships broke the French and Spanish line of battle and ended their challenge to British mastery of the oceans. The Royal Navy remained the greatest maritime force for a further century. Throughout the great oceanic wars, wooden fighting ships had become larger and more heavily armed, some carrying as many as 120 guns. An established ranking of

professional naval officers from midshipman to admiral was created. Regular government departments such as the Admiralty were also organised to administer the increasingly complex affairs of the Fleet.

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century completely changed the fighting ship. Steam replaced sail as the means of propulsion; iron and later steel replaced the wooden hull; and long-range, breech-loading rifled cannon replaced the muzzle-loading smoothbore gun. The invention of the mine, the torpedo, and the submarine also revolutionised warfare at sea. The first battle between armoured ships occurred during the

American Civil War, when on March 9, 1862, the Union ironclad Monitor and the Confederate Merrimack fought an inconclusive battle off Hampton Roads, Virginia.

The changes to sea warfare became a revolution with the construction of HMS Dreadnought in 1905. Every other battleship in the world was made obsolete by her combination of armour, ten twelve-inch guns, steam turbines and relatively high speed. It laid down a gauntlet for the navies of the world: but it was one soon to be taken up.

Germany's decision to undermine Britain's control of the sea was one of the major causes of World War I (1914-1918). Several major naval actions were fought, including the enormous but indecisive Battle of Jutland (31 May 1916). There the great fleets of British and German battleships, battle cruisers and destroyers met and pounded away at each other. Although the Royal Navy suffered the greatest losses, it remained in control of the North Sea. During the rest of the war there was a growing reluctance on the part of the German surface fleet to take on the might of British sea power.

It was the submarine that showed the greatest gain. U-Boats were used extensively by the Germans to attack British trade. This proved to be an effective policy against which the British were slow to develop the convoy system and anti submarine warfare. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy had been at the forefront of submarine developement even though many had initially considered them to be 'a damned un-English invention'. In World War II (1939-1945), the aircraft carrier and airplane became the dominant weapons of conventional sea warfare. The battleship became obsolete although many an Admiral refused to acknowledge this until his ship was sunk beneath him. The British lost HMS Prince of Wales, the Germans the Bismarck and the Japanese the Yamato for little gain. The Royal Navy's final big gun action was the sinking of the German Scharnhorst by HMS Duke of York in

December 1943. Less than forty years after Dreadnought, her successors were already dinosaurs.

Battles - especially in the Pacific Ocean - were fought without the opposing fleets coming in sight of each other, as bombers and torpedo planes inflicted heavy losses on surface ships. This was first seen in 1940 when Swordfish biplanes of the Fleet Air

Arm disabled half the Italian battle-fleet at Taranto. It was a lesson not lost on the Japanese, who repeated it at Pearl Harbour a year later. The medicine was returned at Midway, Coral Sea, the Marianas and later by the British Pacific Fleet as the war progressed. As in World War I, German submarines were a threat to the Allied lifeline across the Atlantic. But convoys, dogged patrolling by destroyers and corvettes, aircraft, radar and intelligence ultimately proved effective in combating them. In the Pacific, the Allied submarines took a heavy toll on Japanese shipping, cutting Japan off from the source of needed raw aterials. Radar and other advancements in electronic surveillance

and communications, also introduced during the war, were at the forefront of technology.

World War II saw the successful maturing of one other form of warfare - that of joint operations and amphibious campaigns. In Normandy,

the Pacific and the Mediterranean, great armadas landed armies that turned the course of the war. It required remarkable planning, new types of ships and tentative steps towards combined operations. The success of the campaigns, however, established the ability of Naval forces decisively to influence the land battle from the sea.

Since the end of World War II, naval warfare has undergone a technological revolution as sweeping as that of the 19th century. The Royal Navy, despite its reduced size, has remained at the forefront of this development. Nuclear propulsion today provides greatly enhanced speed and endurance for submarines, which are no longer handicapped by the need to surface to recharge electric batteries. Guided missiles have replaced guns as the warship's primary weapon whilst organic air power from Short Take Off Vertical Landing Sea Harrier aircraft provides strike and air defence.

During World War II, the U. S. Navy replaced the Royal Navy as the world's strongest. Before its dissolution, the Soviet Union embarked on a massive naval construction program. Although in actual number of ships the Soviet Navy was greater than that of the United States, many of the ships lacked the range, qualities, and tonnage necessary to participate in a global conflict. Nevertheless, the arms race of the Cold War has left a legacy around the world that has conditioned the size and shape of many armed forces, including the Royal Navy, until increasing confidence has allowed the changes of the last three or four years. It is this change to a new world order that largely defines the Royal Navy's shape at the end of this century.

H.M.S. LIVERPOOL

One of Her Majesties Submarines

A flight of Royal Navy Harriers

The crest of H.M.S. Vigilant

In addition to being sailors there were a number of Naval Infantry Battalions. Raised from Naval reservists were the battalions of the Naval Division, although technically sailors they served as soldiers and wore khaki, serving with distinction during WWI. Take a look at their badges here:

The Anson Battalion

The Drake Battalion

The Howe Battalion

The Hood Battalion

The Hawke Battalion

The Nelson Battalion

The Royal Marines also serve in infantry and artillery roles. View their cap badges here:

Royal Marines cap badge, King's Crown, brass

Royal Marines cap badge, Queen's Crown, subdued

Royal Marines Artillery cap badge

Royal Marines Light Infantry cap badge

This photograph is © copyright Peter J. Milford - January 1997 and is used with his permission.

This photograph is © copyright Peter J. Milford - January 1997 and is used with his permission.

This photograph is © copyright Peter J. Milford - January 1997 and is used with his permission.

Enjoy a virtual tour of H.M.S. VICTORY.

LINKS

The Royal Navy and Royal Marines Official Pages

Morgan's Corner - Hearts of Oak