Zygmunt Klukowski

Zygmunt Klukowski

Zygmun Klukowski, "Diary from the Years of Occupation 1939-1944", excerpts

(The pictures are presented here as an illustration only. They are not part of any publication quoted below)

October 11, 1942

...We are shocked over execution of Lejzor Zero. He was our hospital butcher who over the last twenty years delivered meat to the hospital. He leased an orchard from me and was a part of hospital life. Lately he was officialy employed at the hospital with a work card from the labor bureau. He was a wonderful man; everyone liked him. During the last few years he helped me and I helped his family. Every evening he would stop at my office with the latest news. This morning gendarme Syring called him to report to the gendarme station. Zero went without any hesitation because he delivered meat to the gendarmes. After half an hour he left the station with three gendarmes, and they stopped by the city jail to pick up another Jew, Tuchszneider. On a horse-drawn wagon, under escort, they were driven to Michalow, where in a small forest they were executed. Just yesterday I talked with Lejzor about the outcome of the war. He told me he thought the Germans had already lost the war, but he was not sure if we could survive. Everyone is very sad about his murder.

October 18, 1942

A few days ago the Germans finished off most of the Jews in Zamosc. Only twenty or so good mechanics are left. The old people were shot and the younger ones transported to Izbica. The same thing happened in Turobin. I am sure that the same fate awaits the Jews in Szczebrzeszyn. ................

October 21 1942

Today I planned to try to go to Zamosc again. I woke up very early to be ready, but around 6 a.m I heard noise and through the window saw unusual movement. This was the beginning of the so-called German displacement of Jews, in reality a liquidation of the entire Jewish population in Szczebrzeszyn.

From early morning until late at night we witnessed indescibable events. Armed SS soldiers, gendarmes, and "blue police" ran through the city looking for Jews. Jews were assembled in the marketplace.

October 22, 1942

The action against Jews continues. The only difference is that the SS has moved out and the job is now in the hands of our own local gendarmes and the "blue police". They receivedorders to kill all the Jews, and they are obeying them. At the Jewish cemetery huge trenches are being dug and Jews are being shot while laying in them. The most brutal were two gendarmes, Pryczing and Syring.

The Jews that were moved yesterday out of Szczebrzeszyn were held at the Alwa plant. Around 9 P.M. another group of Jews from Zwierzyniec were brought in. Today around noon all were loaded into railroad cars, but by 4 P.M. the train had not moved. It is very cold and rainy. After the Jews were loaded into the cars, factory workers collected and brought to an assembly area money, gold, jewelery, and pearls.

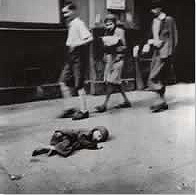

In town some Jewish houses were sealed by the gendarmes, but others were left completly open, so robberies took place. It is a shame to say it but some Polish people took part in that crime. Some people even helped the gendarmes look for hidden Jews. The Germans even killed small Jewish children. It is hard to describe.

It is so terrible that it is almost impossible to comprehend. Legally the Jews don't exist in Szczebrzeszyn anymore, but still many Jews are in hidding. All will be killed sooner or later. I went to city hall today. The total number of Jews killed - they call them disabled - is unknown. Even the best specialists were exterminated. We can feel the shortage of good mechanics.

October 23, 1942

................. While I was gone, the gestapo, local gendarmes, "blue police", and some street people in Szczebrzeszyn again started the hunt for Jews. Particulary active was Matysiak, a policeman from Sulow, and Skorzak, a city janitor. Skorzak had no gun, only an ax, and with the ax he killed several Jews. The whole day people hunted and killed Jews, while others brought corps to the cemetery for burial.

October 24, 1942

In Szczebrzeszyn the hunt for Jews is still on. Additional gestapo agents came from Bilgoraj. With the help of gendarmes, "blue police", and some citizens they looked everywhere for Jews. All cellars, attics, and barns were searched. Most Jews were killed on the spot, but some were taken to the Jewish cemetery for public execution.

I witnessed a group of Jews being forced to march to the cemetery. On both sides of the prisoners marched gendarmes, "blue police", and so-called Polish guards dressed in black uniforms. To speed things up Jews were beaten on their heads and backs with wooden sticks. This was a terrible picture.

Around noon the gestapo ordered that all men over the age of fifteen be ready by 2 P.M., with shovels, to start the burial for the Jews.

I went to gendarme post asking if hospital personnel would be excused from burial work. I was told that physicians would be but all other personnel must report.

Without interruption, Jews from nearby villages are being transported to the cemetery. The dead were brought by horse-drawn wagons.

Philip Bibel, "Tales from the Shtetel", fragment

THE LAST JEW

I donít know if it is instinct, a genetic reason, or a plain and simple need, but every living species seemingly has an uncontrollable drive and urge to return to their birthplace.

The delicate monarch butterfly will travel thousands of miles from the vastness of Canada, through all kinds of adverse conditions, to return to the Carmel area in California, or a particular wooded area in Mexico where it was hatched; there to mate, and to lay eggs in the exact place where it was born.

The same is said about the great Gray whales that live in the ocean. Every year they return from their rich feeding places in the waters of the Artic Circle to give birth to new generations in the same warm lagoons of Baja Mexico in which they were born. The true home is where one was born.

The same deep desire and feeling must also be with humans.

Life in the shtetel was not easy, but this was the only life that they knew. It flowed year in and year out with its normal rhythm; birth, growing up, marrying, having children, and eventually dying, and being buried in the old cemetery.

For 600-700 years, the Jewish people went on this way with their lives. The old Shul, old neighborhoods, the Beth-Olim; everything was right in its place. The four thousand Jews who lived in this old hamlet felt that this normality would go on for eternity - or perhaps until the real messiah would come and bring them back to the Promised Land in Israel.

Unfortunately history has shown us a different fate for the Jews, including those of Shebreshin. Suddenly, in 1939, the great Wehrmacht of Germany, led by the Fascist hordes of the criminal forces of the Nazis, invaded and occupied Poland.

One of their declared master plans was to eliminate all the Jews living in this old land.

Germany, the nation once considered to be the most civilized country in Europe, began the systematic slaughter of the innocents. By 1942 there were no more Jewish people in my town, nor in any of the neighboring towns and villages.

The Jewish inhabitants of our shtetel were led to the old cemetery where they were forced to dig five pits which were to form their own mass graves. Then, devoid of any human dignity, they were all killed, and buried without ceremony in the cold Polish earth.

The whole area became "Juden Rain" Ė clean of the Jews. There were no Jewish witnesses left in our village to count the passing trains of cattle cars packed with other Jews on their way to the nearby Belzec. There, soon after their arrival, they were gassed and burned in the horrible ovens, reducing them to ash that was scattered in the fields, and in the river. "Neat, clean, hygienic, and orderly" according to the the "master race." (No capital letters for those bastards.)

Silence and obedience became the order throughout Poland and Germany. After 1944, when the Nazis were clearly defeated, the citizens of Germany (and their friends) retired to their nice homes, blaming all that happened on others.

"It was all the fault of the Nazis, and no one could stand up to them."

The shtetel, now purely Polish, had changed dramatically. Poverty and destruction were everywhere. A different town tried to cope with its past; tried to heal itself. It was not an easy task.

I have a colleague, Mr. Tomasz Panczyk, with whom I have been corresponding via e-mail for over a year. We send messages to one another about three times a week. We have never met, yet the contact has become personal and intimate.

When I started to write about my old shtetel, trying to describe a form of life that doesnít exist anymore, I had no expectation that anyone would really be interested. I wrote this for my family, so that they might know something about my childhood, and learn a bit about their ethnic and family roots.

I was wrong - very wrong.

My editor put my stories on the World Wide Web, and within days I began hearing from people from all over the world! People actually wanted to know more about this hamlet, Szczebrzeszyn (or Shebreshin)! Some descendents of family members that had lived in this small town wanted to know what I could recall of their family. Some just wanted to hear about the life and the traditions of a town that goes back more than 700 years.

I answered all the correspondence, and then one day an e-mail from my little lost town in Poland arrived. It seems that there is a man, born and raised there, but who now lives in Warsaw, who has his own web site about Szczebrzeszyn. His web site is on a Yahoo server located somewhere in the U.S. His e-mail address is Shebreshin@Yahoo.com.

We started to compare stories. I told Tomasz about a town that I left 75 years ago, when I was a mere child. He, Tomasz, tells me about the town as it exists today. He has mailed me many photos showing how the town has changed, and how it looks now. Some of the buildings that I mentioned in other stories are still there. We both love our birthplace.

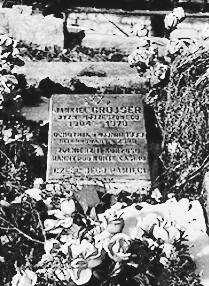

A few months ago he told me a story about a Jew, Mr. Jankiel Grojser, who was born in our township in 1904. He was a soldier in the Polish army at the time that the Nazis invaded Poland. During the course of the war he was interned by the Russians, but he managed to escape and rejoin the Polish army. He distinguished himself in the allied fight when we opened the Second Front in Italy, mainly in the bloody engagement on and around Monte Casino. He was wounded.

After the war Jankiel returned to his old home town. Although I am only five years younger, I canít recall this man, but I remember the very large Groiser family, who like all the Jews of Shebreshin, were slaughtered by the cruel criminal Nazi bastards.

Jankiel came home, the only place he wanted to go, but there was no more home to come to. All the Jews of our shtetel had either been murdered and buried in the mass graves, or had been sent to the nearby Belzec, or Auschwitz, to be gassed and burned in the ovens; their ashes scattered.

He found himself to be the only Jew in an all-Gentile town. Yet it was home. In all of Poland there remained only about 5000 co-religionists. Before the war Shebreshin alone had about 4000 Jews.

Did he want to prove that Hitler did not win by eliminating all the Jews from Europe?

I have tried to put myself in his place. The "homing" instinct is one of the strongest urges; basic, and powerful.

He chose his birthplace. He lived among the ruins with his neighbors, and with the shadows of his ancestors who had resided in this part of the world for all these centuries.

Stories have been written describing that the shock of not finding anyone of his family, Jewish friends from his past, or any Jews at all for that matter, affected his brain. Over time he grew mad. In his lucid moments he could be seen weeping as he sat in the village.

The butterfly had returned to its source, but not to mate and beget a new generation.

In 1970, he died at the age of sixty-six. This created a major problem for the Polish people in Sczebrzerzyn (Shebreshin).

There were no Jews to give him a traditional Hebrew burial. He was not a Christian, and besides, the old Jewish Cemetery was in such shambles that it would be insulting to bury anyone there.

The Polish citizens called a meeting. They would honor this man, this Jew, this Jankiel Grojser, by giving him a dignified resting place in their sanctified, beautiful Catholic Cemetery.

They gave him a big plot. They built a stone fence, and they erected a permanent marker, placing a big Star of David on the top so no one would mistake this as an ordinary grave site.

And the people of the village did not forget this lonely man. I have received photos showing many bouquets of fresh flowers placed on his grave. And as is traditional and customary for Jews, people place pebbles and stones around the monument to indicate that he has had visitors. It is as if they were leaving calling cards. And I am told that some people even bring candles, and light them in his memory.

I look at the photos and I am proud of the people in my birth town Ė that they gave shelter and honor to this lonely man.

I am also very sad about this misplaced human being. I see and feel the loneliness of his lost tribe.

Damn! Damn all those that called themselves "the most civilized people."