THE GREAT HORSE AND THE TIME OF CHIVALRY

The medieval knight is generally perceived as a mounted knight. The clear connection between the rider and his horse has clearly been shown by the various words chevalier, cavalliere, and caballero which show the link between Frenchmen, Italians and Spaniards and their horses. Even in German, the word ritter, means to ride. The name for the code by which the knight was bound, chivalry, derives from the French cheval. It is only in England that the word knight has no direct connection with horses. It is from the Anglo-Saxon word kneht, meaning man-at-arms or servant to the king. It wasn't until the twelfth century that knighthood and chivalry became inextricably associated with gentle birth.

The earliest contenders for the title of knight were the Paladins of Charlemagne's court. These mailed horsemen served the Frankish realm over one thousand years ago, but it is the High Medieval Period (1100-1500) we tend to associate with the knight.

At Hastings in 1066 the Saxon army fought on foot. The horses they possessed were used only for transportation to the battlefield. Once the battle began the horses were left behind. These animals were much smaller than the destriers ridden by the Normans. William of Normandy's warriors knew how to fight on horseback. Their thundering waves broke the back of the Saxon force.

Part of the knight's job was to protect the lord. To pay them for their service, the lord usually gave each knight a piece of land. The knights were loyal to their lord and, in return, the lord was generous to his knights.

To become a knight, the man began as a boy of seven. He was fostered to a relative, or good friend, where he became a page. Much time was spent in building his strength, learning to fight, learning weapons and, sometimes, he was even taught to read and write. The lady of the castle instructed him in good manners, and while being taught the art of knighthood, he also had many jobs to do. For instance, he was expected to help with the menial jobs in the castle, such as setting the table, fetching and carrying for the lady of the manor and cleaning the armor of his knight.

By the time he reached the age of fourteen, he was ready for the next step. He became a squire. As part of his training, in this capacity, he served his knight by taking care of not only his knight's armor, but his knight's weapons, horses and clothes. Squires went everywhere his knight went: tournaments, war games and war. He handed his knight the lances and swords with which to fight and helped him off the field of battle when he was hurt.

At the age of eighteen, the squire could become knighted by his feudal lord, often in a church ceremony. Unlike the gentle sword tap on the shoulder, as seen in the movies, the new knight was actually given a very hard rap on both shoulders with a blunted broadsword. If he was still on his feet after this ceremony, he was said to have earned his spurs.

In the Dark Ages, the knight's war horse was called a destrier. When marching to a war, this horse was not ridden. The destrier was led by the knight's squire on the squire's right side, hence the name destrier which is derived from the Latin dextra, meaning right. A smaller, lighter horse was used by the knight called a palfrey. The palfrey was primarily used for pleasure, but also for display. Although the palfrey was used mostly by ladies, knights could be found riding them, because of the horse's easy going nature and minimal exertion on the part of the passenger. The knights didn't want to have to exert to much energy between engagements and if they rode their war horses it was exhausting to keep them under control.

Most military baggage, including armour and spare weapons, was carried not on carts, but on pack horses, called in Old French sommiers and in the English of the same period capuls, which later term was also applied to horses in agricultural use (mainly for carting).

The horse was the most expensive and significant weapon the knight possessed. The relative value, in terms of the cost and the training of a war horse as opposed to the training of a rounsey (conventional riding horse), was extremely expensive, and the maintenance of his great charger was the knight's full responsibility.

Training methods varied greatly throughout the local areas and the centuries. There are very few records left by the medieval knights on how they trained their horses, but that they were competent and sometimes accomplished horsemen can not be disputed.

To be effective, or even to survive, in the press of battle called for an obedient horse that could be ridden with one hand, or no hands. There cannot be much doubt that the warhorse was trained in movements designed to discourage the close proximity of foot soldiers, intent upon unhorsing the knight. These movements formed the bases of what are termed airs above ground, the rears, leaps and kicks that are still practiced at the Spanish Riding School at Vienna, Austria and the Cadre Noire at Saumur, France. The schooling of horses was most advanced in Spain and France. The most severe training methods were found in Germany and Central Europe.

Of course the airs performed now are more refined when compared to the originals performed on the medieval battlegrounds.

It is difficult to date the origin of the Friesian horse, but it is believed French Norman and Dutch Friesland (Friesian) horses were brought into England in the early part of the 10th Century. There are examples of art work that show that this particular breed is well know in the Middle Ages. Before the use of massive armour necessitated a heavier horse to support the additional weight, the knights rode a light horse that was descended, in part, from the horses of the Roman cavalry. All these chargers had some degree of Barbary blood. Today the Andalusian, Percheron and Shire are the nearest descendants of the Medieval Great Horse.

Stallions were the only sex used in fighting at this time, but it wasn't until much later that geldings and mares were added. They were found to be much calmer and quieter. This made for a better cavalry horse.

The French Norman horse was first used by the knight in war, but as the weight of the armour increased, the development of a heavier horse became a necessity. This horse came about when King John, whose reign lasted only a short time (1199-1216), imported 100 large Flemish stallions to cross with the Norman mare.

Flanders, a country that once lay between France and Belgium, was the forerunner to some of the heavy draft breeds we know today, such as Clydesdale, Belgians and Suffolk Punch.

King Henry VIII wanted the Great Horse to propagate to twice the number that existed in his realm. Therefore he ordered that any citizen owning a certain amount of land had to keep a mare 13 hands (4 inches = 1 hand) or taller to breed with the Great Horse stallions at any time.

It was also at this time he ordered all stallions under 14 hands to be killed on sight. (The lovely Welsh pony suffered a great set back as victim of this law. Luckily some ignored this law.

The many different incarnations of horse types throughout the Middle Ages were dictated by the modifications to the battle armour. Late 12th Century literature mentions covered horses, meaning horses covered with armour of chain mail or quilted fabric. The all encompassing cloth trapping of the covered horse beautifully displayed the Knight's coat of arms in a pattern down the length. On the rare occasions horse armour was used in the 11th Century, it was made of leather or quilting, but by the final decade of the century, a hardened leather facial protection for the horses, known as the shaffron, had appeared.

By the middle of the 13th Century, mail coverings were also used on occasion. They were rare, however, because of the high cost to make them. When used, they were divided into two parts at the saddle; the front section covered the head and neck down to the knees. leaving holes for the ears, eyes and muzzle; the rear half covered the barrel and rump to the hocks.

Horse caparisons emblazoned with the rider's coat-of-arms first appeared on the royal scales in the reign of Edward I, and a roll of purchases of Windsor Park Tournament in 1278 records that horses were fitted with parchment crests. Rivets were used for attaching these crests and were mentioned in the wardrobe accounts of Edward I in 1300.

German Gothic plate armours of the 15th Century were arguably the most beautiful harness ever made, reaching the highest level of artistry in the late 1400s. The German Gothic armour weighted about 71 pounds, which seems quite light, considering the amount of metal used.

The medieval knight in armour did not become a fighting force with which to be reckoned until the introduction of the stirrup. Although some of the Asiatics who invaded Europe in AD 100 had used stirrups, it wasn't until the era of Charlemagne (AD 742-814) that they were adopted by the western civilization. Their adoption was revolutionary, for it enabled a heavily armoured horseman to retain his balance in the saddle whilst using a weighty spear, sword or lance. Previously a chevalier so armed, and wearing mail shirt and helmet weighing some 40lb. would have fallen from his horse if he had attempted any aggressive action against his enemy.

By the Middle Ages the knights still rode with a long leg and with their feet pushed forward. This style is shown in the Bayeux Tapestry when the Normans rode against the Saxons. They held the reins high in the left hand together with the shield leaving their right hand free to handle the sword. Curb bits were in evidence, especially as the sensitivity in the horse's mouth decreased and the cumbersome weight of the armour prevented the knight from subtle use of his reins, so the horses were trained to leg action.

The saddles developed at this time were high at the pommel and cantle to enclose the rider, the stirrups were hung well forward so as to allow the rider to brace himself against the cantle. The reason for this development was because the knights also used heavy lances, tightly clamped between the upper arm and the body, so that the entire weight of the rider and horse was behind the lance.

There are examples of these saddles still in use today, but in a less extreme form, as the Western saddle and the sellsroyals used by the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. The saddles currently used in Portugal and Spain are direct descendants and have changed very little. The major change is the position of the stirrup bars, which are placed further to the rear than on the saddle of the mounted knight.

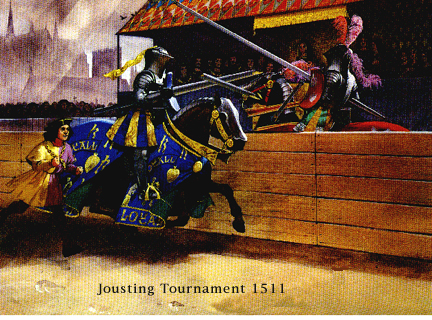

Tournaments or jousts were popular throughout the Dark Ages. The tournaments depicted mimic combat between individual knights or groups of knights or cavalry teams for the amusement of royalty and to sharpen the skills of the knights during peacetime. In the 11th and 12th Centuries, weapons of war was used, often with fatal results. The tourneys were dangerous but this only added to the excitement for competitors and spectators alike.

In 1214, at a single tournament held in Neuess in the lower Rhine region, no less than 50 knights were noted as being killed, a great number of them said to have been "asphyxiated in the dust or trampled to death by the horses."

At first, riders engaged in wrestling, or spearing at the ring (threading a ring, suspended on a gallows, through a lance at full gallop). The quintain was piercing or beheading an effigy at top speed. Then came the best known game, tilting. Tilting is an event where two knights charge each others lances; it was a fearsome display, and the expression, going at full tilt, still survives in common usage to this day. French chivalry decided that the only lance used was either blunted or with a crown of small points on the head.

Laws governing the tourney were codified by Geoffri de Preuilly at the end of the 11th Century, and the knights of England, Germany and France organized themselves into jousting associations. Only knights who could prove four ancestors of equestrian rank could be entered in the index and compete, although the sovereign could confer a right. Courts of marshals, heralds and arbitrators were in control.

Increasingly, the armoured knight became virtual sitting targets and the range and power of cannons and guns eventually toppled the effectiveness of the knight. The first significant victory using gunpowder was probably at the battle of Bicocca in 1522. The killing blow came at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. Armour could be made sufficiently heavy to deflect shot, but it was too heavy to wear; the only alternative defense was mobility and this required the discarding of surplus armour. By the middle of the century, it was clear that the era of the mounted knight in armour was over, but this failed to destroy the romantic reputation for chivalry which has lasted until the present day.

This is my e-mail address if you have any sourses of information on the medieval horses breeds, I would love to have a note from you.

Home

Home