![]()

|

Reading Raswan |

|

The Drinker of the Air PART TWO |

![]()

| AT FIRST it seemed that all the horses had heard the command, but in a moment, though there began a scramble and a rearing and a neighing in the midst of them, the wave of dust and bodies rolled forward. Then from out of the mélée galloped victoriously five noble mares, who aligned themselves in battle formation. They could hardly stand when they assembled before the Prophet, weak from thirst, heat, running and fighting their way out of the press. The "Man of God" laid his hand on their foreheads and inquired for their sires. It was found that they were all half-sisters, their father being the stallion of Dinar al Ansari, the faithful companion of the Prophet, and the names of these noble mares, who alone had preferred the noise of battle to the quenching of their burning thirst, were Abaiyah, Saklawiyah, Kuhailah, Hamdaniyah and Hadbah (or, as it is sometimes given instead, Minikiyah). Thenceforth they were called "The Five of the Prophet from Ed Dinari" to distinguish them from the less esteemed "Five of Al Mahhur." |

| THOUGH THIS is a pretty myth, older by centuries no doubt than Mahomet's time, the question of which choice strains are included within the chosen Five, is of no real importance. All pure Arabs are "Kuhailan," and "Kuhailan" is not actually and originally a strain but the generic term for the thoroughbred Arabian horse. The two hundred and more strains, of which ten or twelve are of distinct value and only three now outstanding (Saklawi-Jidrani, Kuhailan-Ajuz and Miniki-Hadraji), have developed throughout the centuries from Kuhailan-Ajuz, the original, or "old," Kuhailan. |

Arabian steeds in art always appeal to Mr. Raswan. |

| THERE ARE all sorts of picturesque stories,

of course, to account for the various strain-names. The "Hamdani,"

for instance, are named after one of the seven sons of Kahtan and later

after a Bedouin who was called Simri and bred Hamdaniyah mares. At this

time it happened --according to tradition -- that a Saklawiyah mare, who

was pregnant, slipped her fetters and escaped to the desert. None of the

Bedouins could capture her, and, in order to spare her all excitement,

they waited until some weeks after she had foaled. A high prize was then

set for her and her young one, but to no purpose, so swift and enduring

were they. Finally, after mares of all pure strains had failed, Simri sought

to capture her with one of his own Hamdaniyah mares. He was laughed at

because the Hamdaniyah mare is not so fast as the Saklawiyah, Abaiyah and

Kuhailah -- to say nothing of the fastest of them all, the Minikiyah. Nevertheless

he persisted and, when he had followed the mare and her young one for four

hours, the foal became exhausted and allowed itself to be caught and bound.

The Hamdaniyah mare showed no signs of exhaustion, but took up the pursuit

of the runaway anew and, in three more hours, had so tired her out that

she was captured. After that time the Bedouins were wont ot describe the

captor's mare with his name as "Hamdaniyah of Simri," or the

substrain as "Hamdani-Simri."

THIS LEGEND illustrates the general principle involved in Kuhailan strain-names. Certain families specialized in breeding certain strains, and, since the Arabian horse was perfectly pure, they feared no inbreeding and created prepotent strains of such intensified characteristics that here and there outstanding individuals appeared and again, in turn, were specified with an additional word. This added word mostly represented the breeder's name, and for brevity the generic term "Kuhailan" was dropped. Besides the Hamdani-Simri, the Abaiyan -Sharrak -- "the abba-carryingg horse of Sharrak"-- and the four Saklawi substrains are striking examples. The story of the Saklawi runs that a certain Anaza Bedouin possessed four fine Saklawiyah mares. When he was dying, he gave those mares away: the best one to his eldest brother, Jidran; the second to his brother Arkag; the third to his last brother, Ubairan; the fourth to his slave (abd in Arabic). These names are adhered to today, and the Saklwawi-Jidrani still take the first place among the Saklawi. It is known that Abbas Hilmi Pasha bought up most of the Saklawi-Jidrani for unheard-of prices. For example, he paid three thousand Turkish pounds (fifteen thousand dollars) for an old crippled mare that he had brought tO him from Central Arabia by caravan on a specially built vehicle. It should be observed further about the Saklawi-Jidrani that, of certain Bedouins who specialized n breeding them, Ibn Sudan was the most famous, and consequently his horses were known as the Saklawi-Jidrani ibn Sudan. Of this substrain, as I have said, was my beautiful Ghazal. THE STRAINS are of course unimportant unless they are pure. Their faithful representation of a specific type is, as a matter of fact, mostly assured through the ancient custom by which the mare and not the sire bequeaths the strain-name. To my thinking, the name "Al Khamsa" signifies merely an old Bedouin way of telling on the five fingers the most esteemed strains of Arab horses. The individual breeders included whatever they liked best, and with time and regional differences the Five must have changed variously. Suffice it to say that the Kuhailan resemble the ideal Arab, a horse of the Morgan type but more beautiful. The Saklawi look almost like Kentucky saddle horses but have finer heads and a natural head, neck- and tail-carriage. The Miniki suggest the level, long-limbed, somewhat coarser English thoroughbred or race-horse. From the Minniki-Hadraji, indeed is traced the descent of the Darley Arabian, the most important stallion in the history of English race-horse breeding. |

| THOUGH THE asil Arabs have a black and never

a pink or otherwise light-colored hide, they are not black-coated. But,

whether it is an iron-grey or white horse, radiating a silvery light, or

a bay, radiating a golden light, there is always the effect of antique

luster on gold or silver, produced by the under surface of shining, raven-black

skin. Naturally the Bedouins have their preferences among the authentic

colors. Dark chestnut -- the English chestnut -- is considered the color

of the fastest horses (Miniki-Hadraji); iron-gray, the color of the most

enduring (Kuhailan-Ajuz and hamdani-Simri); an and bay, the color indicative

of a well-balanced average of speed and endurance. Such was my Saklawi-Jidrani

Ghazal. The bay or light chestnut or reddish color natural to desert animals

-- lions, gazelles, antelopes, foxes and sso forth -- is most popular. This

is the shade usually called "kumait." It is recorded that a certain

devout Moslem prayed, "My God, let me be in thy sight as is a kumait

before other horses," and it is said also that the Prophet one

day exclaimed, "O God, bless the kumait."

THE BEDOUIN will judge the pure breeding of a horse from its head first. some authors have stated that he will deny any qualities to an Arabian horse if the head is not perfect. This is not true, as I have myself found out. We must make a distinction between a Bedouin who is merely a lover of Arabian horses and one who is an expert in horse-flesh and breeding at the same time. Most Bedouins are primarily just fighters and hunters, and very few have intuition, love and that innate gift -- of more value than experience -- for breeding the highest type of Arabs. Some do it out of pride and some out of jealousy. some have selfish or financial interests at heart, and very few do it for the love of seeing the finest and most noble blood perpetuated. The last-named, those "fanatics" who breed for purity only, read the strain, type and unsullied records from the head of the horse first. Abbas Hilmi Pasha was a fanatically orthodox breeder, though not a Bedouin. Prince Muhammad Ali is perhaps the most outstanding one. Ali Pasha Sherif was famous for that reason, and Lady Anne Blunt, after thirty years' experience in Arabia and Egypt, was a convert and did not change during her last twenty years. Yet not by the standards of these distinguished stud-owners, nor by those of any Bedouin, would the head alone be a sufficient test of pure breeding. The conformation and soundness of the whole horse would have to be taken into account, but it has almost always been proved that a specimen perfect physically and mentally went with a perfect head. |

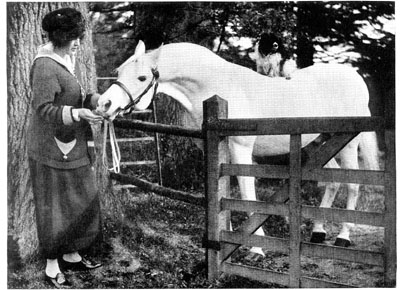

In her stud at Crabbet Park, in England, Lady Wentworth holds the rrest horse blood outside of Arabia. She is seen here with the last historical scion of the stud of Prince Potocki (destroyed by the Bolshevists) -- the pure white Arabian stallion Skowronnek, whose fame reaches over the world today. Below is a pure Arab in the typical listening posture

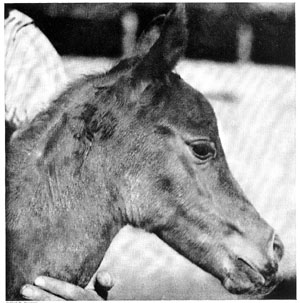

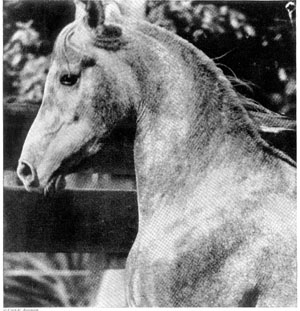

Typical of the beautiful head of an Arabian foal is this eight-hour-old filly, out of a Saklawiyah-Jidraniyah ibn Sudan dam by a Kuhailan-Jalabi sire. Not because he either dies not reproduce or is killed off, but because his blood is increasingly contaminated by careless breeding, the "asil,"or noble, Arab is in danger of dying out  To Mr. Raswan these heads of Arabs from the breed of Prince Muhammad Ali are reminiscent of the sculptured frieze of the Parthenon, which aroused in him his first love of Arabian horses. He thinks it neither bold nor challenging to credit the noble Araian horse with perfection

|

| PEDIGREES ARE issued only on demand, attested

with the thumb-print or seal of the sheikh or the owner of the horse or

both. It is perhaps just as well that there are no written records among

Bedouins: memory and conscience serve them better, and, as it happens,

a change of one letter in the Arabic word for "writer" makes

it mean "liar."

BUT ASK a Bedouin if such and such a mare is "asil,"and, if he says so, it is absolute truth. One day last winter Naif, the young son of Sheikh Mishaal ibn Faris, of the Amud Shammar, took me to a tent and showed me a very beautiful mare. "Is she 'asil'? " I inquired. "We do not know," was his answer. He could not even reveal the strain-name of the mare. I wanted to buy her. She was priced at only sixty gold pounds, and she was worth six hundred at least. I was willing to give more than sixty pounds for her, but I needed her pedigree to be able to register her later in America. NEITHER THE sheikh, however, nor anybody else would testify to her breeding. "But she is a Saklawiyah," I said. Anybody who knew Arabian horses could see that she was a Saklawiyah -- a typical one too. But was she Saklawiyyah-Jidraniyah, as she appeared to be, or something else? They would not testify to her strain and family strain at all. They would say only that she was "taken" in a ghazu against the Amarat Anaza and that her owner had been killed. The new owner explained: "The traders from Central Arabia buy our Shamaliyah mares and those of unknown origin because they look only for fast horses, and we do not need to give them any pedigrees except those for our own young colts, which we truthfully know." THE MARE was then offered to me as a gift, but I had to explain that, according to government requirements and the regulations of studbook officials, I could not export her to my homeland for breeding purposes without a certified pedigree and that I should be doing her an injustice to take her along like an ordinary horse. At this they all exclaimed, "Wallahi, she is asil!" But this testimony to her authentic blood was not sufficient in regard to her strain, and reluctantly I had to go away without her. Three months later, as it happened, an Amarat arrived at Sheikh Mishaal's camp to receive the blood-price for his dead relative. Then only was it revealed that this mare was a Saklawiyah-Jidraniyah, and, when word to that effect was conveyed to me, I was six hundred miles away among the Ruala Bedouins. TO THE Bedouins the horse has one great purpose. She (the collective name for "horse"is faras, meaning "mare") is esteemed according to her usefulness in war and on raids, and in general she alone is used for riding. Yet the strain is named for her, and the strain-name inherited from her. Inasmuch as it is a trait of the Arab to carry tendencies to extremes, an Arab sire will fix and intensify in the offspring the characteristics of the dam. Hence the greatest care must be taken in the choice of a mare for breeding purposes. If she is blessed with an even temper and all-around good qualities (including height, since it is she and not the stallion that gives the height), the Arabian sire will increase these qualities in the foal to such a degree that subsequent horse generations up to fifteen will benefit from this one influence. YET THE Arabian mare, though priceless in the eyes of the Bedouin, is expected to undergo the most trying ordeals. In camp she wears a pair of wooden hobbles or, when an enemy may be near, patiently carries a heavy iron chain, fetters and lock around the front pastures. For days and weeks she follows the dhalul, or racing-camel, on a raid, tied to the cinch of the camel's saddle and ready to carry her master, if the enemy is sighted, at a flying gallop into the fray. She may have to walk for eighty miles or more. Even in the foaling season, which begins in February, she is ridden to her last day, and, if her time comes in the midst of a fight, her owner retires with her temporarily to a quiet place. She gets little rest after foaling and sometimes so little food -- perhaps not even a handful of barley or dates twice a day -- that she lacks sufficient milk for her young one. THE PROPHET forbade mutilation of the teeth, ears and forelock of the growing horse, but he did not forbid the gelding of a stallion. The Bedouin's custom, however, is never to castrate his colts. He sells what he does not wish to keep, usually when they are a year and a half old. Fillies he does not sell, except for financial, political or friendly reasons. He will sometimes lend a mare to a warrior and receive half of the spoil, or he will sell her to various others and share in her offspring. One man may own her "near fore leg." another her "off hind leg." and so on, and in succession, then, the different men will claim the foals that are born of her. But I have seen Bedouins mutilate mares in order to make them seem less desirable to would-be purchasers or to enemies. ONCE IN a Fidaan Anaza camp, before the World War, I sw a Bedouin use a most curious method of detracting from the value of a perfect mare that he did not intend to sell. He forced her to touch pork, in the presence of some city Arabs from Deir ez-Zor, because the Turkish provincial officer, known to be very "religious," had an eye on her and had sworn to get possession of her. The witnesses, in oriental fashion, carried the news to the Turkish officer that this animal ate pork to retain her beauty and power of endurance, and thereafter the Bedouin and his "infidel"mare lived in peace. MARES OF purest blood can still be obtained in the desert, as I discovered again last year; but how to acquire them is not a simple question of money. They are usually typical, small Arabs, not above 14.2 hands high, and they do not as a rule find favor in the eyes of us Occidentals. They have the most perfect and characteristic head marks, but are often in a pitiable condition from overuse and the hard, rough life in the desert. An American friend of mine, visiting with me an Anaza camp and hearing me "rave" about such a specimen, gave up in despair and said: "Keep your antiques for yourself! I have seen what I want in Damascus, Hama and Deir ez-Zor." Perhaps herin lies the reason why so few pure and outstanding Arabian horses have been exported. Those that can be bought are the good-looking and well-nourished ones left in the camps because they are useless for raids. TO BE able to buy a mare of high physical and mental quality is good luck indeed; for to possess her is to own a treasure. But, though she may be worth many thousands of dollars, a Bedouin would rather give her to you, if you were his friend, than part "dishonorable" for money with the best he has. His mare has brought him honor only. She has knelt down beside him when he was wounded, so that he could mount easily. She has watched over him while he slept and roused him at the approach of man or beast. There are no names to sweet for her, no comparisons too good. He may be poor, but in the council of the sheikh his mare is so respected that his friends rise when he enters, in tribute to her, the war-mare of renown. When they pass her, they put their hands on her forehead and call her blessed. I DO NOT mean to imply, by all I have said about the mare, that the stallion is unimportant. Among fanatically orthodox breeders he is chosen from the same strain, if possible, as the mare; that is, a Kuhailan stallion for a Kuhailah mare, a Saklawi stallion for a Saklawiyah mare and so on. However, since this is almost impossible, the various tribes have preferred strains, from which they select stallions to be mated to mares of any of the choice strains. Serving a mare is free. "We do not sell the love of our horses." say the Bedouins. A breeder who allows his mare to be covered from a stallion of the same strain only, has to do much inbreeding, yet without damage to the offspring. The Arab in the desert may be considered as pure in blood as the wild lion or the zebra, both of which closely mate without bad results. To the Bedouins inbreeding is the highest test of pure blood in Arabian horses, since by this means the characteristics of the particular strains are preserved strikingly and brought ot greatest perfection in the progeny. Personally I belong to this class of breeders. THE CHIEF criticism that I hear of the Arab is, "He is so small!" Yet he is a greater weight-carrier than larger horses and develops greater powers. One of the finest endurance records known in this country was made by Razzia, a chestnut Arabian stallion, foaled in 1907, whom Captain Tompkins, 10th Cavalry, U.S.A., rode in an official test on October 30, 1913, from Northfield Vermont, to Fort Ethan Allen and back -- 104 miles in 15 hours and 30 minutes. The Arab is distinguished by longevity as well as endurance. He lives to be about thirty-four, twelve years longer than other breeds. Also, instead of the "washy" substance often found in larger horses, he has firmness and elasticity in the tendinous and fibrous contexture, and he gains in size up to 15.1 hands, when bred in Europe and America, without losing the compressed quality of his heritage as a desert animal. Nevertheless his size really counts for little, since, as I have said, the mare gives the height. How often has a 16-hand cross-bred horse been produced from an Arabian stallion of 14.2 hands! 'If the size of the Arabian stallion mattered, we could not have seen reproduced with Arabian stallions of the same size Welsh mountain ponies, hackneys, thoroughbreds and other breeds. MODERN EUROPEAN interest in horse-breeding, which has become an American interest, too, was brought about by a kind of revolutionary incident in the tribal life of Central Arabia, the beginning, that is, of the great migrations of the Anaza and Shammar Bedouins, after the middle of the seventeenth century, to the northern pastures. This movement extended suddenly as far as the middle Euphrates and to the very gates of Damascus and even Aleppo. In 1715 the Darley Arabian, a stallion imported to England some years previously from the Anaza Bedouins in the neighborhood of Aleppo, produced Flying Childers. The first volume of the English Stud-Book was not published until 1808, but, from the time of the Darley Arabian on, there was an attempt to collect and preserve pedigrees and records. The foundation of the English thoroughbred race-horse rests solidly and historically on the Byerly Turk, the Darley Arabian and the Godolphin Barb. All Hackney pedigrees as well trace to the son of the Darley Arabian, who was the speediest race-horse of his time, since it was Blaze, son of Flying Childers, who, bred to a Norfolk mare, produced Shales, the first typical hackney, about 1755. I MYSELF advocate the breeding of the Arab, not to have him take the place of established types that have been created for special purposes, but in order to perpetuate his own type and special qualities of health, power, endurance, gentleness and beauty, and to save his rare blood, which is disappearing fast from the earth. The asil Arab is indeed dying out, not because he either does not reproduce or is killed off, but because his blood is continually and increasingly contaminated by careless breeding. There are in existence a million and a half or more of so-called "Arabs" or "Orientals," but, in addition to the hypothetical eight hundred first-class Arabs left in Arabia there are not more than fifteen outstanding individuals on the continent of Europe, sixty in England, forty in America and seventy in the rest of the world -- fewer than a thousand all told. The Beddouins themselves, fated as they are to endure modern upheavals and the demoralizing impact of the West, cannot preserve the authentic blood. Nor can the present Arab studs do so, since their future is not guaranteed. The outstanding studs during the past century were in Egypt, Hungary, Russia and England. They have disappeared, except for the one containing the marvelous remnants saved at Crabbet Park by Lady Wentworth out of the two studs owned by her mother, Lady Anne Blunt, in Egypt and England. Crabbet Park includes also, besides the choice of the disposal sale of the Khedive's stables and of the world-famous stud of Ali Pasha Sherif, the last historical scion of the stud of Prince Potocki in Russia -- the pure white Arabian stallion Skowronek. The name of this horse reaches over the world today, especially into Arabia, whence the Bedouins and other Arabs have traveled as on a pilgrimage to England to kiss his forehead and bless him and his owner. Yet, though Lady Wentworth holds the rarest blood outside of Arabia, it is not absolutely certain that Crabbet Park will not some time in the future fall into the hands of unskillful or indifferent breeders. The United States, therefore, seems to be the place in which there is most lively hope of saving the Arab breed, since some of the best blood is available here, though scattered, and there is an interest in the enterprise not only among breeders but in the American Remount, which has placed proved Arabian sires in horse-producing states all over the country for the benefit of civilians. DATA IN plenty could be cited to support my view of America as, for matter-of-fact reasons, the logical future home of the asil Arab, but my purpose here has been, not to state or argue a thesis, but rather to present the Arab as, let us say, a source of esthetic interest -- a work of art no less precious than are those masterpieces of painting and sculpture and poetry which the world will not willingly let die. I think it neither bold nor challenging to credit the noble Arabian horse with perfection. To this, indeed, beyond all other creatures that man has subjected to his hand, has it been given, because of a beauty that is spiritual as well as physical, to take possession of man's soul. Next month Carl R. Raswan will write of his first experiences with Bedouin in Arabia.

ASIA Volume XXIX Number 4 Contents and Contributors for April 1929 Carl R. Raswan, specialist in Arabian horses and lover of all things Bedouin, set sail from New York in January for another visit to his friends in the deserts of the Near East. He has lived for some eight years in various Arab countries and speaks Arabic fluently. A German by birth and upbringing, Mr. Raswan is now an American citizen. At Maynesboro Farm, in Berlin, New Hampshire, where he spent a large part of last year with Mrs Raswan and their three children, a three-year-old is lamenting. "Why can't we all go to Arabia?" |

![]()

|

Davenports: Articles of History Arabian Visions' Archives |

This page hosted by ![]()

Get your own Free Home Page