|

|

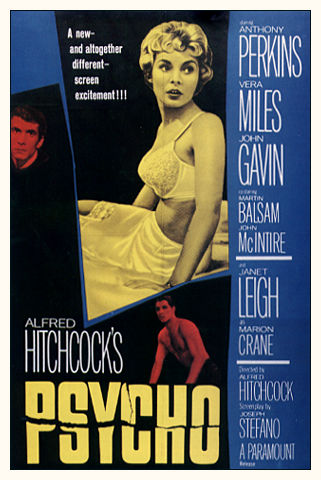

This is, of course, the film for which Alfred Hitchcock is most famous -- a horror film, most people might call it. But to say that about Psycho is a little like describing Hamlet as a play about a confused young man who doesn't much like his family. Or that van Gogh's Starry Night is a distorted vision of the Dutch countryside. Or that Oedipus is about a neurotic royal clan. The statements are more or less true in a crude gradeschool way, but they don't begin to describe the richness and depth of each work.

In fact, Psycho continues to impress audiences (and filmmakers) more than thirty years after production and to spin off (one could hardly say "inspire") hundreds of poorer imititations not because it's a shocker, but because of other, deeper themes -- themes, images, and ideas of which we're perhaps only casually or obliquely aware until after multiple viewings. For this film is really a meditation on the tyranny of past over present. It's an indictment of the viewer's capacity for voyeurism and his own potential for depravity. It's also a statement on the American dream turned nightmare, and there's a running concern for the truth that physical vision is always only partial and that our perceptions often tend to play us false -- thus Hitchcock's insistence, from the opening shot, of staring eyes that are finally empty, blank, and dead. Psycho is also -- and this doesn't exhaust the contents -- a ruthless exposition of American Puritanism and exaggerated Mom-ism. Made in black-and-white with a television crew in six weeks with a cost of $800,000, it has earned something in excess of $40 million, which says something about economy. And success.

For most, a first viewing of Psycho is marked by suspense, even mounting terror, and by a sense of decay and death permeating the whole. Yet, for all its overt terror, repeated viewings leave one mostly with a profound sense of sadness. For Psycho describes, as perhaps no other American film before or since, the inordinate expense of wasted lives in a world so comfortably familiar as to appear initially unthreatening: the world of office girls and lunch-time liaisons, of half-eaten cheese sandwiches, of motels just off the main road, of shy young men and maternaol devotion. But these become the flimsiest veils for moral and psychic disarray of horrifying proportions.

Psycho postulates that the American dream can easily become a nightmare, and that all its facile components can play us false. Hitchcock reveals the fraudulence of the fantasy that a woman can flee to her lover and begin an Edenic new life, forgetting the past: love stolen at midday, like cash stolen in late afternoon, amounts to nothing. He shatters the notion that intense filial devotion can conquer death and cancel the past, and he treats with satiric, Swiftian vengeance the two great American psychological obsessions: the role of Mother, and the embarassed secretiveness that surrounds both lovemaking and the bathroom.

These concerns, these vulnerabilities, raise Marion Crane and Norman Bates almost to the level of prototypes -- thus Hitchcock's insistence on audience manipulation and the resulting identification of viewer with character. It's this that accounts for the films continuing power to touch us, its terror and poignancy undiluted after three decades and multiple screenings. Broader in scope than the bizarre elements of its plot indicate, Psycho has the dimensions of great tragedy, very like the Oresteia and Crime and Punishment. In method and content, in the sheer economy of its style and its brave, uncompromising moralism, it's one of the great works of modern American art.

Back to Pete's Pad | Movies | Hitchcock

Text copyright © Donald Spoto, The Art of Alfred Hitchcock, 1976.