| Writers: | Pierre Boileau (novel), Alec Coppel, Thomas Narcejac (novel), Samuel Taylor |

| Composer: | Bernard Herrmann |

| Director of Photography: | Robert Burks |

| Cast: | |

| Raymond Bailey | Doctor |

| Barbara Bel Geddes | Midge |

| Ellen Corby | Manageress |

| Tom Helmore | Gavin Elster |

| Henry Jones | Official |

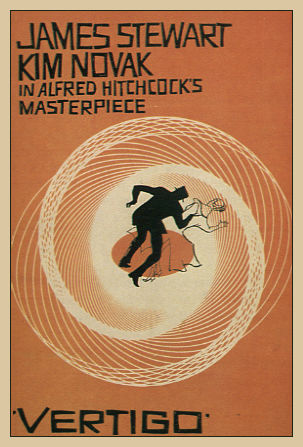

| Kim Novak | Madeleine/Judy |

| Lee Patrick | Older Mistaken Identification |

| Konstantin Shayne | Pop Leibel |

| James Stewart | Scottie Ferguson |