Ray Gun issue 50 October 1, 1997

![]()

| pretty, dee p |

|

"I really wish that I didn't give a shit, and sometimes I really try to cultivate that, you know?"

![]() Tanya Donelly is sitting in an Italian restaurant across the street from Fort Apache, legendary Boston recording studio and also home of her management company. She's trying to convince me that nothing in the world would please her more than to develop a slings-and-arrows-proof hide.

Tanya Donelly is sitting in an Italian restaurant across the street from Fort Apache, legendary Boston recording studio and also home of her management company. She's trying to convince me that nothing in the world would please her more than to develop a slings-and-arrows-proof hide.

![]() "I can barely watch the news," she continues, "and that's weak, and I don't want to be weak. I'm so completely overwhelmed by the bullshit of life. I don't have a tough skin, I wish I did."

"I can barely watch the news," she continues, "and that's weak, and I don't want to be weak. I'm so completely overwhelmed by the bullshit of life. I don't have a tough skin, I wish I did."

![]() "Surely you don't want to turn into one of those cynical, prematurely jaded people," I prompt.

"Surely you don't want to turn into one of those cynical, prematurely jaded people," I prompt.

![]() "I do, I do, I really do!" insists Tanya.

"I do, I do, I really do!" insists Tanya.

![]() "But that's so boring. The world is filled with those kinds of people." I reach for the bottle fo wine between us, and start to pour some more into her glass, before noticing that there's only enough left for one glass. I check myself, and pour the remaining wine into my glass instead. "Ah, fuck you," I tell Tanya, by way of explanation for my rudeness. "See? You don't want to turn out like me."

"But that's so boring. The world is filled with those kinds of people." I reach for the bottle fo wine between us, and start to pour some more into her glass, before noticing that there's only enough left for one glass. I check myself, and pour the remaining wine into my glass instead. "Ah, fuck you," I tell Tanya, by way of explanation for my rudeness. "See? You don't want to turn out like me."

The release of Love Songs for Underdogs marks Tanya's first solo excursion, but it's hardly the work of a neophyte. Beginning with her mid-'80s work with half-sister Kristin Hersh in seminal Newport, Rhode Island alt-rockers Throwing Muses, carrying on through a short sidetrip with the Breeders, and most prominently, as singer/songwriter for Belly, whose 1993 hit "Feed the Tree" helped fuel the early-'90s alt-rock boomlet, Donelly has a pedigree few Fiona-come-latelys can match. That experience is put to good use on Love Songs, which features some of the most wide-ranging and confident music of her storied career. In many ways, the new record is a family affair: Tanya recruited old friends like David Lovering (Pixies), David Narcizo (Throwing Muses), Stacy Jones (Letters to Cleo, Veruca Salt) and her husband, Dean Fisher (Juliana Hatfield), to play with her\- a fair sampling of the the talent that made late-'80s/early-'90s Beantown such a fomidable scene. Eight of the album's 12 tracks were co-produced by Donelly with Wally Gagel, with the remainder done by her manager, Gary Smith, a noted producer and owner of Fort Apache studios (and a damned nice guy, to boot). The Smith-produced tracks, including the first single, "Pretty Deep," tend to have a slightly "bigger," more raido-friendly quality, but the whole fits together seamlessly, even as Tanya experiments with (for her) stylistic quirks such as strings and drum machines ("Mysteries of the Unexplained," "Lantern," respectively), and, on "Bum," an attempt at a Mama Cass impersonation ("As close as someone of my stature can get," jokes the diminutive Donelly).

![]() The week I arrive has been spent in rehearsals with her new backing band at Fort Apache, in anticipation of an upcoming party at the studio where Tanya will debut several songs from the new record. Her band consists of, in addition to Tanya's singing and (much-underrated) guitar-playing, Fisher on bass, Narcizo on drums, Elizabeth Steen on keyboards and accordion, and Rich Gilbert on guitar. Despite the fact that these guys have only been playing together for the better part of a

The week I arrive has been spent in rehearsals with her new backing band at Fort Apache, in anticipation of an upcoming party at the studio where Tanya will debut several songs from the new record. Her band consists of, in addition to Tanya's singing and (much-underrated) guitar-playing, Fisher on bass, Narcizo on drums, Elizabeth Steen on keyboards and accordion, and Rich Gilbert on guitar. Despite the fact that these guys have only been playing together for the better part of a

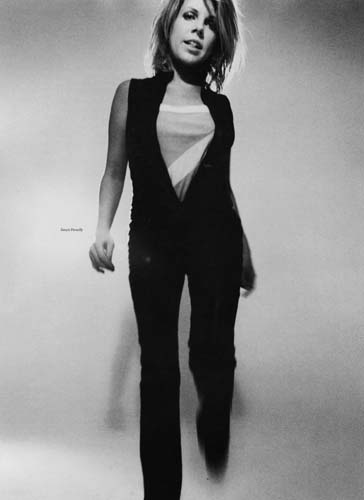

TANYA DONELLY, LATE OF BELLY, BREEDERS, AND THROWING MUSES, STRIKES

OUT ON HER OWN FOR THE FIRST TIME. JIM GREER BEGS HER TO REMAIN SENSITIVE

AND VULNERABLE IN A SENSATION-HUNGRY WORLD.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ERIC JOHNSON.

week, the band already sounds almost as tight as Donelly's last outfit, Belly, did in its heyday. Part of this proficiency can be ascribed to the supernal competence of Narcizo, a truly extraordinary drummer, but throughout the rehearsals it's hard not to notice the infectious enthusiasm each of the players birngs to the material. Which is something you didn't really get out of later-day Belly.

"For a while I was sort of saying that it was musical differences only," says Tanya of the breakup of her last band, "but that's never true. There were personality conflicts that arose from the musical differences, and everything just sort of fell apart. It was very mutual. That's the upside of it -- that is was mutual. We broke up before the friendships could be completely destroyed."

![]() "Do you still talk to those guys?" I ask.

"Do you still talk to those guys?" I ask.

![]() "Yeah, I do. Chris and Tom [Gorman, Belly's drummer and guitarist]. Gail [Greenwood, Belly's bassist] is in L7 now. She's doing great. She loves it. She's really happy. She calls them her soul sisters."

"Yeah, I do. Chris and Tom [Gorman, Belly's drummer and guitarist]. Gail [Greenwood, Belly's bassist] is in L7 now. She's doing great. She loves it. She's really happy. She calls them her soul sisters."

![]() "When did you break up, exactly"

"When did you break up, exactly"

![]() "About six months before we told anybody," replies Tanya, digging into her pasta. "It's hard to pinpoint. We were on tour, and it was becoming apparent that we weren't gonna be able to do anything together again, safely."

"About six months before we told anybody," replies Tanya, digging into her pasta. "It's hard to pinpoint. We were on tour, and it was becoming apparent that we weren't gonna be able to do anything together again, safely."

![]() "Did the breakup have anything to do with the relatively disappointing sales of your second album?"

"Did the breakup have anything to do with the relatively disappointing sales of your second album?"

![]() "On some level, probably," she answers evenly. "We were disappointed. But we would have broken up even if the album had done really well -- and maybe even sooner. I think we would have broken up no matter what happened. There was disappointment there, and that... People aren't at their most graceful in an unsuccessful situation."

"On some level, probably," she answers evenly. "We were disappointed. But we would have broken up even if the album had done really well -- and maybe even sooner. I think we would have broken up no matter what happened. There was disappointment there, and that... People aren't at their most graceful in an unsuccessful situation."

![]() The perceived failure of King seemed at least in part to prompt a spate of articles about the "sophomore slump" of formerly successful alt-rock bands. I remember reading, say sometime in '94 or '95, that "alternative is dead."

The perceived failure of King seemed at least in part to prompt a spate of articles about the "sophomore slump" of formerly successful alt-rock bands. I remember reading, say sometime in '94 or '95, that "alternative is dead."

![]() "It always amazes me when people don't learn from history," offers Donelly. "Things move in cycles all the time, and when somethings like that happens, and there is a glut of bands, people think that there's an assumption [by the bands] that `Okay that's it -- we have arrived. There is music now.' It's never the case. That's never happened."

"It always amazes me when people don't learn from history," offers Donelly. "Things move in cycles all the time, and when somethings like that happens, and there is a glut of bands, people think that there's an assumption [by the bands] that `Okay that's it -- we have arrived. There is music now.' It's never the case. That's never happened."

![]() It must seem especially weird for Donelly, coming for her perspective in the Muses -- who never really sold a boatload of records, and who never really expected to -- that all of a sudden there were these absurd commercial expectations placed on bands who had previously never considered things like chart position.

It must seem especially weird for Donelly, coming for her perspective in the Muses -- who never really sold a boatload of records, and who never really expected to -- that all of a sudden there were these absurd commercial expectations placed on bands who had previously never considered things like chart position.

![]() "Yeah," concurs Tanya. "It's interesting being a `dinosaur' and talking to the `younger fold' in bands and the attitudes are so different now. Just from like playing radio festivals and meeting other bands and stuff like that, there's such a ... the expectations that are placed on them are so high that I can't see how they can possibly grow in that kind of heat, you know? People get signed out of their basements now, and don't have a chance to really figure out what they're even interested in playing before they have this massive record deal, and it ultimately wrecks them."

"Yeah," concurs Tanya. "It's interesting being a `dinosaur' and talking to the `younger fold' in bands and the attitudes are so different now. Just from like playing radio festivals and meeting other bands and stuff like that, there's such a ... the expectations that are placed on them are so high that I can't see how they can possibly grow in that kind of heat, you know? People get signed out of their basements now, and don't have a chance to really figure out what they're even interested in playing before they have this massive record deal, and it ultimately wrecks them."

![]() "That's partly the bands' fault, though, isn't it?"

"That's partly the bands' fault, though, isn't it?"

![]() "I know. There is a `We should have.' That's a key. Like that's the norm. There is definitely like a `Where's my piece?' attitude now that didn't exist when we started."

"I know. There is a `We should have.' That's a key. Like that's the norm. There is definitely like a `Where's my piece?' attitude now that didn't exist when we started."

After Belly went belly up, Tanya took some time off, rarely leaving the house and only desultorily working on new material. In the Spring of '96, she began soloing in earnest.

![]() "At what point did you decide you were gonna make a solo record?"

"At what point did you decide you were gonna make a solo record?"

![]() "Immediately," says Tanya. "Yeah, 'cause I started to feel like I've been involved in so many things that it would be just too confusing and sort of... whorish to enter into yet another band situation. And there was a little bit of a bitter divorcee in me, kind of like `I'm not gonna play with anybody, screw this, I don't need anybody.' Which was really infantile and which I've gotten over. It was sort of a decision made more out of defeat that confidence, in a weird way.

"Immediately," says Tanya. "Yeah, 'cause I started to feel like I've been involved in so many things that it would be just too confusing and sort of... whorish to enter into yet another band situation. And there was a little bit of a bitter divorcee in me, kind of like `I'm not gonna play with anybody, screw this, I don't need anybody.' Which was really infantile and which I've gotten over. It was sort of a decision made more out of defeat that confidence, in a weird way.

![]() "I had a little bit of a bad time the winter after we broke up. I didn't leave the house for a while. I was writing songs, sort of, but tentatively. Gary [Smith]'s ownership of Fort Apache is really convenient for me. I can sort of just walk down the street. Book like a week here and a week there."

"I had a little bit of a bad time the winter after we broke up. I didn't leave the house for a while. I was writing songs, sort of, but tentatively. Gary [Smith]'s ownership of Fort Apache is really convenient for me. I can sort of just walk down the street. Book like a week here and a week there."

![]() "What's the main difference between working in a band situation and working alone? There are things on Love Songs that seem so different from stuff you've done in the past. I don't really see you bringing a song like `Lantern' to Belly, for instance."

"What's the main difference between working in a band situation and working alone? There are things on Love Songs that seem so different from stuff you've done in the past. I don't really see you bringing a song like `Lantern' to Belly, for instance."

![]() "I don't know," she replies. "Let me think about that. I'm so unconscious about things, I just don't...I do things very intuitively, I don't ever really know why I'm doing anything. Which isn't really the best way to live your life, sometimes. Most of the time when I'm writing a song I have it in my head, and I have different parts in my head, which when you work with other people you have to suppress sometimes, because you can't tell people what to play in a band situation. Whereas on 70 per cent of this record, I got to play what was in my head. It's good though, because the songs that we did with Gary were very much band songs, and by that time I had been really missing that aspect of playing with people. I was getting kind of lonely."

"I don't know," she replies. "Let me think about that. I'm so unconscious about things, I just don't...I do things very intuitively, I don't ever really know why I'm doing anything. Which isn't really the best way to live your life, sometimes. Most of the time when I'm writing a song I have it in my head, and I have different parts in my head, which when you work with other people you have to suppress sometimes, because you can't tell people what to play in a band situation. Whereas on 70 per cent of this record, I got to play what was in my head. It's good though, because the songs that we did with Gary were very much band songs, and by that time I had been really missing that aspect of playing with people. I was getting kind of lonely."

![]() "So how is it working with your husband?"

"So how is it working with your husband?"

![]() "It's fine. It's better than being separated. We still have little kinks that we have to work out, but we're definitely the type of couple that's better together than separated. We get a little nutty when we're apart."

"It's fine. It's better than being separated. We still have little kinks that we have to work out, but we're definitely the type of couple that's better together than separated. We get a little nutty when we're apart."

![]() "Was having him in the band an immediate and obvious decision?"

"Was having him in the band an immediate and obvious decision?"

![]() "No, not at all. Actually, it was something that we avoided for a long time. Of course I shot my mouth off, `He's not gonna be in the band, we're not gonna do that, it's so lame, blah blah blah,' then like two months later I just felt like I didn't

"No, not at all. Actually, it was something that we avoided for a long time. Of course I shot my mouth off, `He's not gonna be in the band, we're not gonna do that, it's so lame, blah blah blah,' then like two months later I just felt like I didn't

TANYA DONELLY-PRETTY DEEP

STYLIST-JENNIFER ELSTER

MAKE UP-JORGE SERIO FOR JED ROO. HAIR-GIANNANDREA FOR GARREN NY

WORLD DOMINATION JUMPSUIT, FAB 208 TANK, HELFIRE SHOES

want us to be separated. 'Cause our last tour, when he was on tour with Juliana [Hatfield], we saw each for like a month out of the year. It was ridiculous."

![]() "And now that the Throwing Muses have broken up, you get ot work with David Narcizo again. How did that come about? Did it cause any tension with Kristin at all?"

"And now that the Throwing Muses have broken up, you get ot work with David Narcizo again. How did that come about? Did it cause any tension with Kristin at all?"

![]() "Not at all. They're still gonna work together on her solo stuff. My relationship with Kristin is the best it's ever been right now. It's just rekkids, after all. It's kind of nice, because it's back to feeling like there's this little community of friends that all play together. There was a real separatist feeling for a while."

"Not at all. They're still gonna work together on her solo stuff. My relationship with Kristin is the best it's ever been right now. It's just rekkids, after all. It's kind of nice, because it's back to feeling like there's this little community of friends that all play together. There was a real separatist feeling for a while."

![]() "Differing degrees of commercial success inevitably cause tension."

"Differing degrees of commercial success inevitably cause tension."

![]() "Yeah," agrees Tanya. "Especially if they're your sibling. You've already got that in there anyway. In that situation, though...the reason that I play music is because I know Kristin Hersh. I wouldn't be doing this now if not for her. I was getting ready to go to college. I had a whole career in anthropology planned out."

"Yeah," agrees Tanya. "Especially if they're your sibling. You've already got that in there anyway. In that situation, though...the reason that I play music is because I know Kristin Hersh. I wouldn't be doing this now if not for her. I was getting ready to go to college. I had a whole career in anthropology planned out."

Our conversation, possibly under the influence of the wine, wanders from music to books and architecture (despite the fact that I know almost nothing about either ), before I notice that my tape has almost run out, and in a last-ditch effort at something approaching professionalism, try to steer the conversation back to Tanya's record.

![]() "Uh, what's that song `Pretty Deep' about?"

"Uh, what's that song `Pretty Deep' about?"

![]() "Exactly what we're taling about, actually," replies Tanya.

"Exactly what we're taling about, actually," replies Tanya.

![]() I make a concerted effort to remember what we were just talking about. Her thin skin. Her inability to deal with the world. My hogging the wine. Okay.

I make a concerted effort to remember what we were just talking about. Her thin skin. Her inability to deal with the world. My hogging the wine. Okay.

![]() "There's a few like that [on Love Songs], on the `living well in an unwell world' theme I seem to be preoccupied with. Just getting overwhelmed and sucked in by the undertow. It's just about how people more than ever want to see something gross, want to see something twisted, they go out of their way --"

"There's a few like that [on Love Songs], on the `living well in an unwell world' theme I seem to be preoccupied with. Just getting overwhelmed and sucked in by the undertow. It's just about how people more than ever want to see something gross, want to see something twisted, they go out of their way --"

![]() "All right, speed it up, sister," I bark, glancing nervously at the rapidly advancing tape counter on my battered machine.

"All right, speed it up, sister," I bark, glancing nervously at the rapidly advancing tape counter on my battered machine.

![]() "Toconcentrateonsomething... I don't know. It's such a voyeuristic world. I have no problem with voyeurism if it's purely objective, but people actually want to involve themselves in...the pox of life. (laughs) You know what I mean? Like `Cops.' `Cops?' Shit like that."

"Toconcentrateonsomething... I don't know. It's such a voyeuristic world. I have no problem with voyeurism if it's purely objective, but people actually want to involve themselves in...the pox of life. (laughs) You know what I mean? Like `Cops.' `Cops?' Shit like that."

![]() "I have no idea what you're talking about," I confess.

"I have no idea what you're talking about," I confess.

![]() She looks at me with mock exasperation, and shrugs, "People. I can't deal with them."

She looks at me with mock exasperation, and shrugs, "People. I can't deal with them."

( taken from the middle minus 8 pages )

![]()