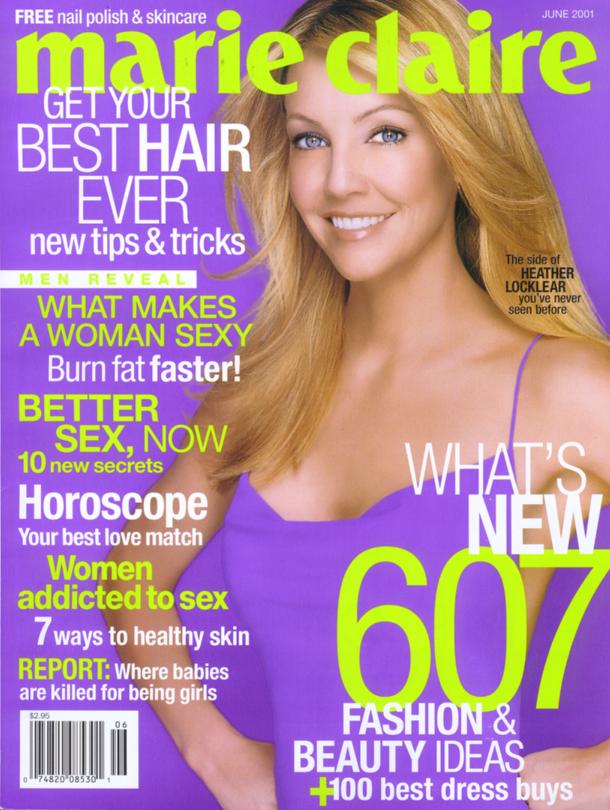

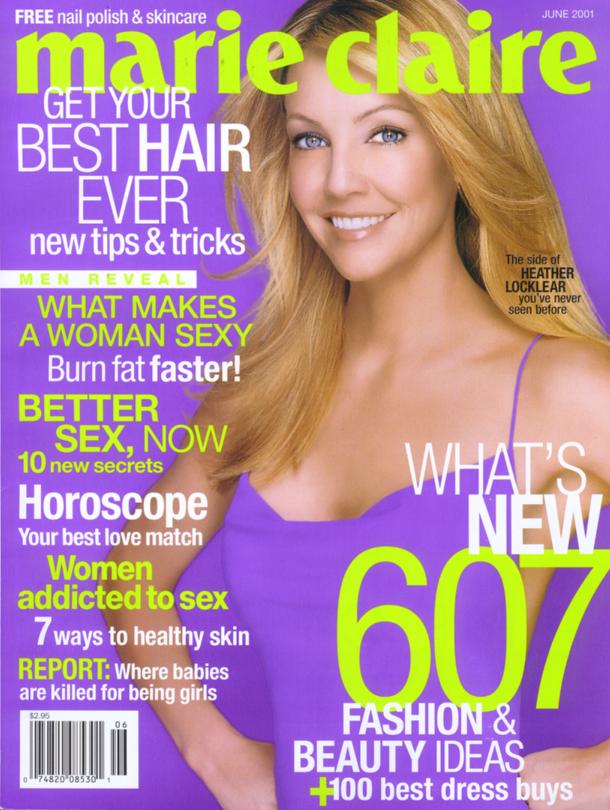

marie claire | CELEBRITY CHALLENGE

HEATHER HEATHER

LOCKLEAR

GOES TO

BOOT

CAMP

BY MARSHALL SELLA

As the daughter of a Marine colonel, Heather wanted to find out if she could survive in the military. So we sent her to her father's training camp. There, she narrowly escaped getting slashed by barbed-wire spikes—and faced an obstacle course that makes powerful men cry

1000 hours

On a perfect, government-issue Southern California morning, Camp Pendleton is what it always is: sunny and 72 degrees, hilly terrain interrupted only by bayonet-like trees and rows of armored vehicles. But today there is a buzz in the air, and its name is Heather Locklear. She is here not to entertain, but to surrender herself to an arduous day of U.S. Marine Corps Infantry training. As the door of her limo swings open in a dusty lot, the first thing seen is a camouflage-green pant leg: not military issue but military glam, the latest style by Tark 1. "Instead of a canteen," she whispers, "I've stashed some bottled water into my Prada bag."

She is born of a long line of military folk—daughter of a Marine colonel who served in the Korean War, granddaughter of a World War I veteran—and has come to test herself against the family tradition. As proof of her pedigree, she is wearing three silver dog tags. The most battered of them is punched with the name Harper Locklear, her grandfather; two others bear her dad's name. "This tag is the gruesome one," she says, flashing her father's second ID in the sun. "If you die in combat, they put it in your mouth"—she clacks her teeth violently—"and they kick your mouth shut. That's how they identify you later." She is born of a long line of military folk—daughter of a Marine colonel who served in the Korean War, granddaughter of a World War I veteran—and has come to test herself against the family tradition. As proof of her pedigree, she is wearing three silver dog tags. The most battered of them is punched with the name Harper Locklear, her grandfather; two others bear her dad's name. "This tag is the gruesome one," she says, flashing her father's second ID in the sun. "If you die in combat, they put it in your mouth"—she clacks her teeth violently—"and they kick your mouth shut. That's how they identify you later."

It's hardly an average day for Heather, who at 39 is the ultimate survivor of American television, from Dynasty to Melrose Place to Spin City. Her world does not faintly resemble that of the 35,000 Marines at Camp Pendleton: She admits to being a voracious shopper and that she loves, loves, loves to relax in a tub of pulsating sea-salt water and indulging in massages. Her father laughingly calls her and her husband, Richie Sambora (lead guitarist of Bon Jovi), "sushi people," adding that she was always athletic as a girl but is even tougher now, due to a hiking regimen and the rigors of chasing after her three-year-old daughter, Ava. "That," she says, "is the real obstacle course."

The wisdom of hurling Heather Locklear into this trauma, all to test whether any olive-drab blood runs through her veins, is dubious. Aside from the possibility that she'll crack under pressure, there is the risk of injury, which is too terrible to contemplate.

Even hours later, that grim specter looms in our minds as Heather, loudly provoked by a staff sargeant named Rucker, scrambles on her back beneath a jumble of barbed wire. Her face, the trade and treasure of L'Oréal, is millimeters from a device built specifically to slash and repel anyone near it. As instructed, she tries to use her rifle to prevent the spikes from ripping her flesh, but the tension of the steel is against her. All the while, Rucker and his fellow officers shout her along with baffling commands: "Inch it up! Roll it down! Roll it!"

But the Marines have no intention of making the news by damaging an American sex symbol, so the day does not begin at such a fever pitch. Uninspired by Tark 1, quiet men with Beretta sidearms equip Heather with less-flattering duds and, within minutes, all 5'5" of her is decked out in precisely the same fabric and color as everyone else, as far as the eye can see.

1200 HOURS

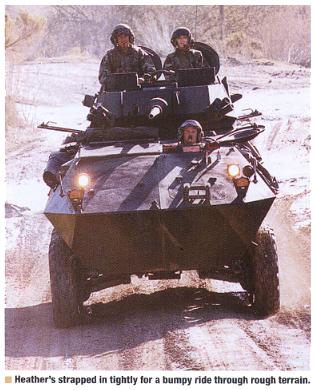

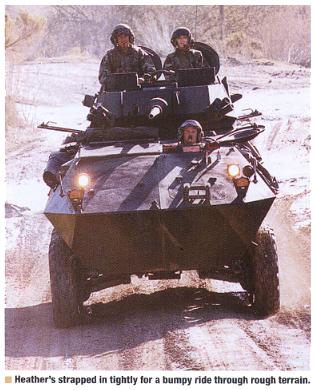

She clambers onto a Light Armored Vehicle (LAV) to be shuttled to her first stage of training. A senior officer mutters words of concern to his men, but Heather is oblivious. She is perched at the top of the LAV like a kid on a Tilt-a-Whirl, and she is ready to ride. And the LAV obliges, with more than 14 tons of steel bucking and heaving through thick ponds of pudding-thick mud. Smiling broadly in her helmet and googles, Heather looks absurdly like a bug with perfect teeth, riding some sort of gargantuan, ultra-violet frog. Occassionally, she holds on to the top of her helmet, as though it might blow off like a bonnet in the breeze. She clambers onto a Light Armored Vehicle (LAV) to be shuttled to her first stage of training. A senior officer mutters words of concern to his men, but Heather is oblivious. She is perched at the top of the LAV like a kid on a Tilt-a-Whirl, and she is ready to ride. And the LAV obliges, with more than 14 tons of steel bucking and heaving through thick ponds of pudding-thick mud. Smiling broadly in her helmet and googles, Heather looks absurdly like a bug with perfect teeth, riding some sort of gargantuan, ultra-violet frog. Occassionally, she holds on to the top of her helmet, as though it might blow off like a bonnet in the breeze.

After half an hour of being battered around by the LAV at 60 miles per hour, we arrive at an area that's denoted as Range 131, but it's known locally as The Million-Dollar Town That No One Lives In.

The town is like any other, except that it's a complete ruin. Warfare in the modern age has lost its clarity—these hollow buildings, meant to simulate a hostile city, are a crucial training ground. Heather has been brought here to learn the art of seige. The Marines are not shy about explaining why this funny little town is here. In certain battles, when troops have entered a city like this, they have lost 85 percent of their men. And, it can take up to seven Marines to overcome a single enemy if defenders are hiding in buildings like these. In a real sense, Heather has known these men all her life; the statistics are very real to her.

She is led to a structure at the make-believe corner of B Street and Third Avenue. Nearby is a sort of debris one would find in an embattled city: a charred ambulance, an overturned car. The place is a scrupulously maintained disaster area. Heather is fascinated by the layout but suddenly looks distracted. "I lost my elastic hair thingy," she says, before realizing the frivolity of her remark. "I guess I'll have to tough it out somehow."

After 40 minutes of instruction, full of useless detail about "turret ops" and "woodland-squad action," Heather is presented with an M-16 rifle. She is concerned: "With . . . with all these people here?"

"Don't worry," says a wry captain named Royer. "You ain't gonna shoot anybody." Still, as she sweeps the barrel of the weapon past us, even the instructors subtly duck.

There are many ways to invade a building. In this case, Heather gamely agrees to try a "two-man support," in which two Marines use a piece of wood to lift a third into a second story window.

Two grunts step up. With one overly powerful motion, they hoist Heather up and, for a moment, the entire crew witnesses the unnerving spectacle of Heather blurting out "Jesus Christ!" and splaying through an open window, her legs flying apart just before she vanishes into unseen clatter. After a moment, she re-emerges from the lower level and sardonically demands that the record reflect she has a broken nail—one of the perfect, pale fingernails that she was proudly showing off only hours before.

"Look at that color," she says, admiring it as a kind of final tribute. "Delicate."

"So it's called 'Delicate Pink'?" I ask.

She tilts her head mournfully. "Just 'Delicate.'"

1400 HOURS

Danger, as every warrior knows, comes when you least expect it. For lunch today, Heather had insisted on eating what the troops eat, thus exposing herself to the bane of the infantry: MREs, or "Meals Ready to Eat."

The classic MRE contains about 2500 calories and has a shelf life of no less than 12 years. Heather's packet is stamped with the phrase CHIX AND RICE, though the chicken turns out to be pink inside and the rice is, to be utterly fair, like rice. But she eats her half-cooked meat with abandon, as if it were a variation of sushi. "I'll eat anything," she chirps. "And this is . . . something." The classic MRE contains about 2500 calories and has a shelf life of no less than 12 years. Heather's packet is stamped with the phrase CHIX AND RICE, though the chicken turns out to be pink inside and the rice is, to be utterly fair, like rice. But she eats her half-cooked meat with abandon, as if it were a variation of sushi. "I'll eat anything," she chirps. "And this is . . . something."

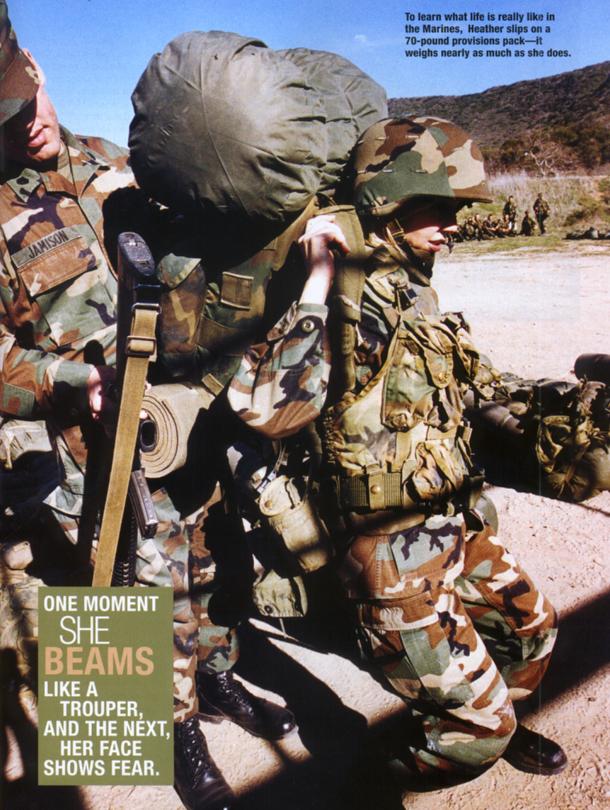

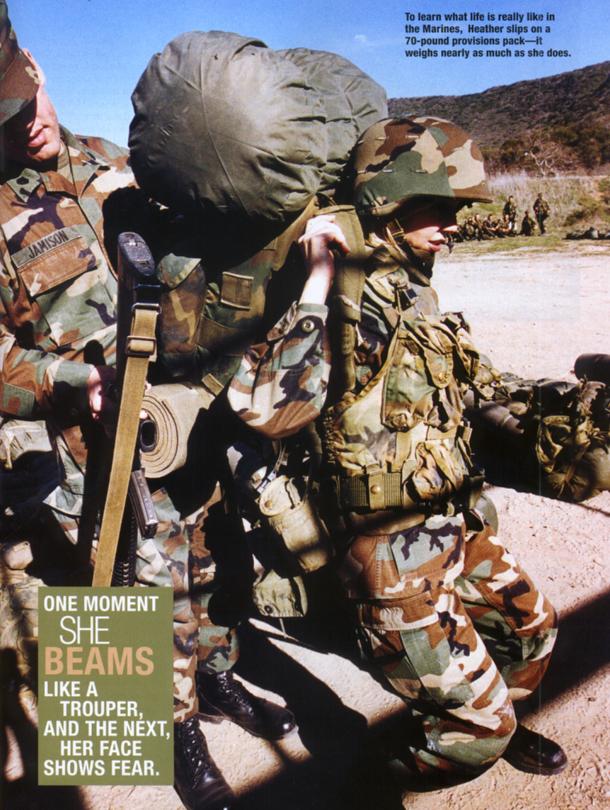

To work off this "food," Heather is fitted with a regulation pack. Fully loaded, these can weigh 70 pounds, which, for Heather, is not far from carrying an identical twin on her back as she tries to brandish an assault rifle and elude various obstacles. This is how Marines stay mobile.

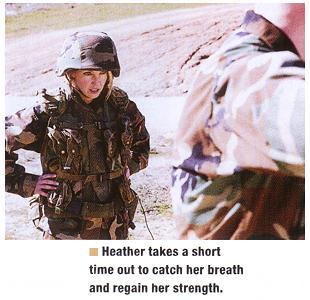

Still, for every moment she beams like a trouper, there is another when she takes on a darker aspect. For her, the unreality of it all seems to invoke the reality of it all. In one exercise, Heather storms a building as part of a squad. "It's the spookiest thing," she says later. "There's no way to tell which guy is which, and I run into one room when, suddenly, someone is firing at me. And all I can think is, I want to get out. I want to hide. Then I realize—that's always the guy who gets killed. It's terrifying."

When she lurches out of the front of the building, officially "dead" by the rules of the drill, she looks rattled.

After another harrowing LAV ride—it feels like an ongoing, 30-minute car accident—we arrive at the focus of our dread: the obstacle course in which Heather will learn the art of the bayonet.

1500 HOURS

Pendleton's Bayonet Assault Course is a geometric arrangement of chaos, an opportunity for recruits to be injured in the safest possible setting. There are high dual-bars that one must flip onto and between; walls to be scaled; green rubber mannequins to be stabbed again and again. Upon our arrival, a powerful Marine in his early 20s is lying on the ground with an excruciating leg cramp, and tears are streaming down his face.

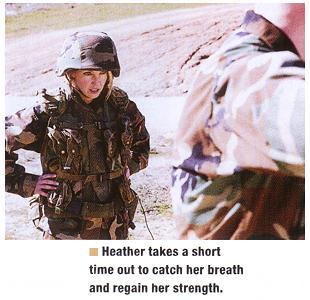

To add to the surreal quality of the stress at hand—and here it becomes clear that Heather's visit is not a very well-kept secret—every recruit in sight has a camera. It's as though Rita Hayworth has risen from the dead and gone on a one-stop USO tour to boost morale. Everyone needs a picture with Heather Locklear, and she indulges all requests, even in brief moments of rest between obstacle runs. To add to the surreal quality of the stress at hand—and here it becomes clear that Heather's visit is not a very well-kept secret—every recruit in sight has a camera. It's as though Rita Hayworth has risen from the dead and gone on a one-stop USO tour to boost morale. Everyone needs a picture with Heather Locklear, and she indulges all requests, even in brief moments of rest between obstacle runs.

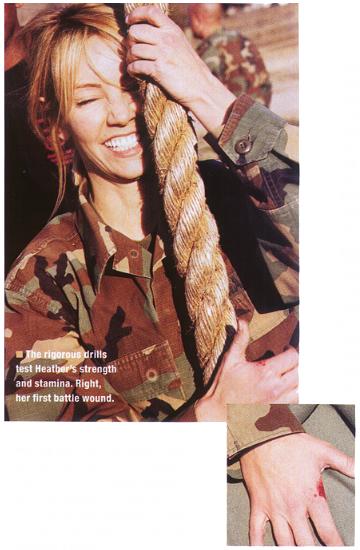

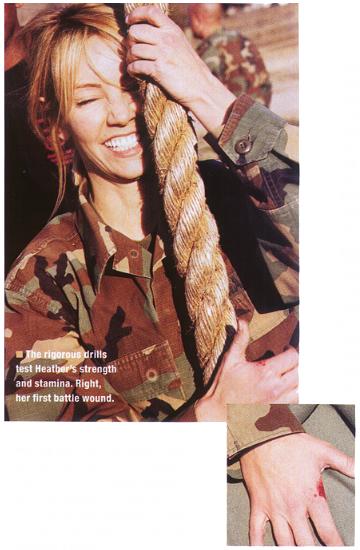

Heather eats the course alive, scarcely even getting winded despite the long day. She scuttles under the barbed wire—first on her belly, then face up, just like everyone else in the line. She negotiates the high dual-bar with greater ease than some of the burliest recruits. "There's a trick to it," she keeps saying. "It's all about shifting your weight."

The bayonet seems all too familiar to her. Each of the hapless mannequins receives three deep stabs to the chest before someone notices that Heather is the one who is shedding blood. Real blood.

Suddenly, men are on walkie-talkies calling for a corpsman, rubbing alcohol, and gauze. The only person on the range amused by all this is Heather herself, who uses the interlude to pose for more pictures with the boys, always assuming the same pose: one foot atop the other, knee bent, and a sex-kittenish expression on her face that says, Here's me and my old pal, just like always.

"Seems like when I stabbed that guy, he stabbed me back," she jokes, though it's clear that the barbed wire was the culprit.

Rucker is delighted by the scratch. "All right!" he barks. "This course is new and we just got our first combat wound. You christened my course!"

A few weeks later, Heather's hand has finally healed—but her face was left "trashed and peeling," she says, due to the dusty abuses of the LAV rides. "I wouldn't say the course dragged me out," she says breezily. "But my first call from the limo was to Richie, to get my martini ready."

|

HEATHER

HEATHER

She is born of a long line of military folk—daughter of a Marine colonel who served in the Korean War, granddaughter of a World War I veteran—and has come to test herself against the family tradition. As proof of her pedigree, she is wearing three silver dog tags. The most battered of them is punched with the name Harper Locklear, her grandfather; two others bear her dad's name. "This tag is the gruesome one," she says, flashing her father's second ID in the sun. "If you die in combat, they put it in your mouth"—she clacks her teeth violently—"and they kick your mouth shut. That's how they identify you later."

She is born of a long line of military folk—daughter of a Marine colonel who served in the Korean War, granddaughter of a World War I veteran—and has come to test herself against the family tradition. As proof of her pedigree, she is wearing three silver dog tags. The most battered of them is punched with the name Harper Locklear, her grandfather; two others bear her dad's name. "This tag is the gruesome one," she says, flashing her father's second ID in the sun. "If you die in combat, they put it in your mouth"—she clacks her teeth violently—"and they kick your mouth shut. That's how they identify you later."

She clambers onto a Light Armored Vehicle (LAV) to be shuttled to her first stage of training. A senior officer mutters words of concern to his men, but Heather is oblivious. She is perched at the top of the LAV like a kid on a Tilt-a-Whirl, and she is ready to ride. And the LAV obliges, with more than 14 tons of steel bucking and heaving through thick ponds of pudding-thick mud. Smiling broadly in her helmet and googles, Heather looks absurdly like a bug with perfect teeth, riding some sort of gargantuan, ultra-violet frog. Occassionally, she holds on to the top of her helmet, as though it might blow off like a bonnet in the breeze.

She clambers onto a Light Armored Vehicle (LAV) to be shuttled to her first stage of training. A senior officer mutters words of concern to his men, but Heather is oblivious. She is perched at the top of the LAV like a kid on a Tilt-a-Whirl, and she is ready to ride. And the LAV obliges, with more than 14 tons of steel bucking and heaving through thick ponds of pudding-thick mud. Smiling broadly in her helmet and googles, Heather looks absurdly like a bug with perfect teeth, riding some sort of gargantuan, ultra-violet frog. Occassionally, she holds on to the top of her helmet, as though it might blow off like a bonnet in the breeze.

The classic MRE contains about 2500 calories and has a shelf life of no less than 12 years. Heather's packet is stamped with the phrase CHIX AND RICE, though the chicken turns out to be pink inside and the rice is, to be utterly fair, like rice. But she eats her half-cooked meat with abandon, as if it were a variation of sushi. "I'll eat anything," she chirps. "And this is . . . something."

The classic MRE contains about 2500 calories and has a shelf life of no less than 12 years. Heather's packet is stamped with the phrase CHIX AND RICE, though the chicken turns out to be pink inside and the rice is, to be utterly fair, like rice. But she eats her half-cooked meat with abandon, as if it were a variation of sushi. "I'll eat anything," she chirps. "And this is . . . something."

To add to the surreal quality of the stress at hand—and here it becomes clear that Heather's visit is not a very well-kept secret—every recruit in sight has a camera. It's as though Rita Hayworth has risen from the dead and gone on a one-stop USO tour to boost morale. Everyone needs a picture with Heather Locklear, and she indulges all requests, even in brief moments of rest between obstacle runs.

To add to the surreal quality of the stress at hand—and here it becomes clear that Heather's visit is not a very well-kept secret—every recruit in sight has a camera. It's as though Rita Hayworth has risen from the dead and gone on a one-stop USO tour to boost morale. Everyone needs a picture with Heather Locklear, and she indulges all requests, even in brief moments of rest between obstacle runs.