Political Stars

& TV Stripes

By Dee Dee Myers

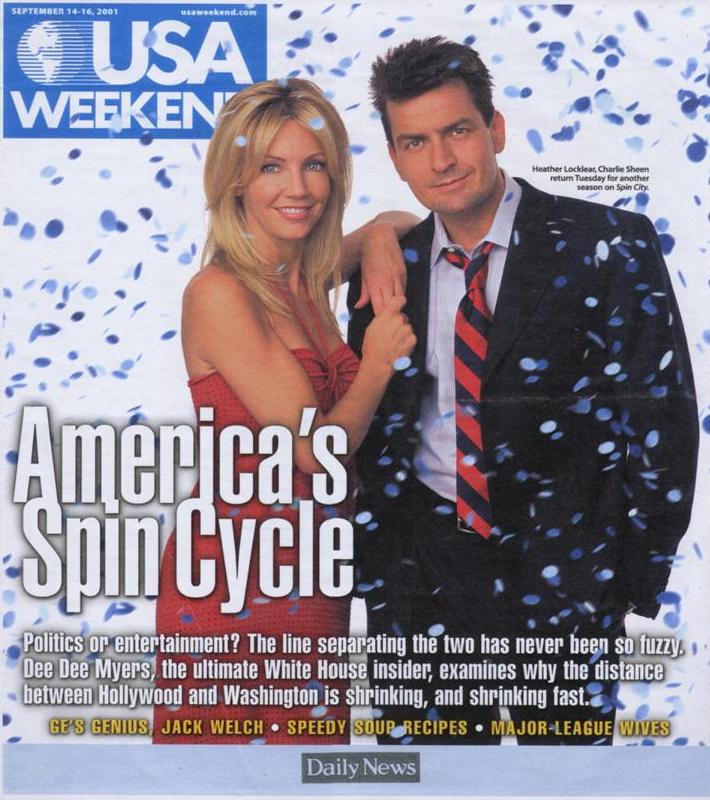

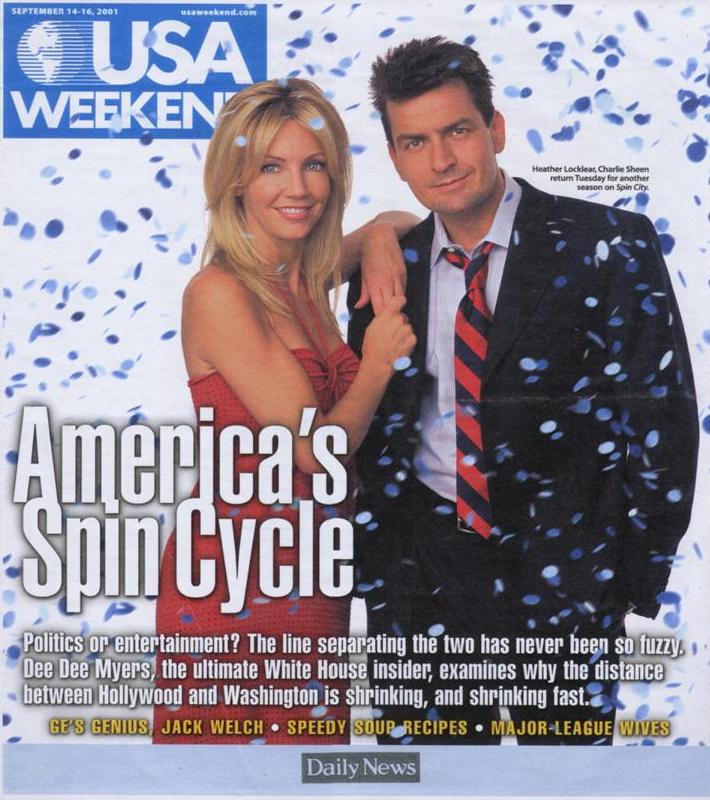

Politics. Entertainment. The line between them never has been more blurred. A former White House press secretary, now a consultant for NBC's hit The West Wing, puts things in focus.

When I first met with Aaron Sorkin to discuss a pilot he'd written for a TV series about a fictional White House, the planets seemed aligned against him. Washington was consumed by the Monica Lewinsky scandal, and real people seemed disillusioned by politics. Even though I liked the pilot and agreed to work as a consultant on the show, I left the meeting feeling pretty confident it would never get made.

What was I thinking?

As we now know, the show did get made, and it's a hit. Even my inside-the-Beltway friends—the same ones who called and e-mailed me after the first few episodes to complain that there were too many people walking quickly through the hallways, so it just didn't feel like the real White House—have become addicts. Sorkin describes the series as a "workplace drama" rather than a show about politics. But politics—particularly as it is practiced in the inner sanctum of the White House—provides a compelling backdrop.

"It's a battlefield where there are winners and losers, and you can keep score," Sorkin says. "Any time people disagree intelligently, it's entertaining. And the White House is a world of gigantic and complicated issues, of strategy and intrigue and glamorous characters. We want to peek behind the scenes."

In other words, politics has all the elements of good drama. But in an age when everything is judged by its entertainment value, the lines between politics, news and fiction have never been fuzzier. Novels are written about sitting presidents in real time. Reporters are bigger stars than the newsmakers they cover. And entertainers want to be taken as seriously as the secretary of State. Who can blame the public for being confused?

Although I might not have described it quite the same way then, my years in the Clinton White House definitely were dramatic. Every day was a new adventure, as the president raced from drafting a budget to bombing Baghdad to managing scandals about his personal finances and marital fidelity. And even though all of those stories received press coverage, the ones that got the most attention weren't necessarily the ones that affected the most people. Rather, they were the ones where the conflicts were clear, the issues were easy to understand and, above all else, someone's fate hung in the balance. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to point out that the press and the public are paying more attention to Chandra Levy's disappearance than to President Bush's plans to overhaul Social Security. A story that includes sex, lies, power, betrayal and a missing person always will trump a debate about when the "trust fund" will go broke. And in many ways, it's always been like that.

"In the old days, people would go out to a Fourth of July picnic to hear political speeches for two or three hours. If you're gonna hold people's attention for that long, you'd better make it fun," says Chris Matthews, host of the MSNBC/CNBC talk show Hardball. In other words, Matthews says, it had to be both "bread and circus."

Certainly, it's always been circus. Great politicians always have been a match for the moment, tapping into new and exciting ways to communicate with people. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became a master of the radio, drawing listeners close with his intimate fireside chats. John F. Kennedy understood the dawning power of television and made the most of his youth and charm. Ronald Reagan, with his sunny optimism and regal bearing, created the modern "photo op," giving him maximum exposure with minimum risk.

But what about the bread? For most of the last century, our political institutions grappled with big and compelling issues, from World War I to the Depression and from World War II to the Cold War. Against this backdrop, political stories were full of tension, and the actors who populated them seemed larger than life. "The Cold War infused politics with a good story," says Mark Halperin, the political director at ABC News. "The threat that everyone on the planet was going to be annihilated by nuclear war was, by definition, compelling."

But now all that has changed. In the aftermath of the Cold War, political crises are treated like garden-variety celebrity scandals. O.J. Simpson's murder trial, JonBenet Ramsey's murder and President Clinton's impeachment all received the same huge amount of media coverage, particularly on high-volume cable news programs and in the supermarket tabloids. And depending on what you watched or read, it could be difficult to tell what was more important.

Had Watergate occurred after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the media coverage certainly would have included a comic element. Imagine G. Gordon Liddy on Hardball back then, describing how he held his hand over a burning candle without flinching to prove his toughness. Instead, everyone proceeded cautiously because they knew that to weaken the president was to weaken his ability to protect the nation from extinction.

If Monica Lewinsky had delivered pizza to a president who was going toe-to-toe with the Russian Bear, the resulting scandal would have been treated much more soberly. In fact, it's possible there never would have been a scandal—no independent counsel, no Starr Report, no impeachment trial—because the public, the press and even the president's Republican opponents might have been reluctant to go down that road, given the stakes.

We'll never know. But it is clear that as the stakes have shrunk, so has the seriousness with which we treat politics. Perhaps that's inevitable, even appropriate. And it certainly isn't limited to politics in a culture where everything seems to be treated less seriously. "There are no limits," says Jon Macks, a former political consultant and now a writer on The Tonight Show With Jay Leno. "Drug rehab used to be something we were ashamed of; now, it gets you a guest shot on Ally McBeal."

Like it or not, real issues now are resolved according to these new rules, and it hasn't always served to elevate the debate. "Health care got acted out in the popular culture," says Sean Daniel, a movie producer with the two Mummy blockbusters among his credits. He argues that "good casting and good writing" were responsible for the success of the "Harry and Louise" ads that helped sink President Clinton's health care proposal. "They worked as politics and entertainment, and while they definitely dumbed down the debate, they also helped change it."

Political talk shows on broadcast and cable networks certainly seek to inform and entertain, and in some ways they succeed. "I learned from Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan that if you want to build support for things you care about, you have to be able to communicate," says U.S. Rep. David Dreier, R-Calif., a frequent guest on those shows. "And to be effective, you have to do it in an entertaining, appealing and comedic way."

But even careful politicians such as Dreier have to pick their shots, because much of what drives the shows, especially on cable, is the scandal du jour. Too often, serious debate is crowded out by ideological, salacious or just plain loud argument. It's not surprising, then, that some people have argued that shows such as The West Wing actually can do a better job of explaining serious issues than the news media can. Although liberals find more to love than conservatives do, the show gets high marks from both groups for its thoughtful discussions. And every week, I get requests from individuals and interest groups who want The West Wing to feature their pet projects and issues because they believe they will reach more people there than on CNN.

Despite all the changes, politics is still entertaining. As fact, it still gets plenty of attention, even if that attention is less serious than it once was. And as fiction, it still provides a compelling backdrop for contemporary drama, even if the stories are smaller. I've always believed in the ability of our political system to adapt to changing times and remain relevant, and I still do. But there are risks along the way. As the lines between information and entertainment blur—and the gravity of the issues in play diminishes—perhaps the news media can afford to treat a constitutional crisis like a sex scandal, cranking up the most off-color aspects to attract readers and viewers. But if they move too far in their desire to entertain, people may seek fictional venues, conceived primarily as entertainment, to learn more about real issues.

Hmmm. Sounds like a good premise for a new show.

DEE DEE MYERS was the first woman to serve as White House press secretary. She's now a contributing editor to Vanity Fair magazine, a consultant on The West Wing and a member of the California State University Board of Trustees.

|

Ken Burns' Prime-Time Civics Quiz

Burns, a USA WEEKEND contributing editor and arguably America's pre-eminent historian, wants to see if you can tell TV politics from the real thing.

On ABC's Spin City, the mayor of New York City is campaigning for a second term. In real life, if he won, would this be his last term?

Answer: Not necessarily. The city's mayors are limited to two consecutive four-year terms, but he could run again four years later.

In a new Fox series, 24, a presidential candidate is the target of an assassination attempt on the eve of his party's convention. Does the Secret Service guard potential nominees in real life?

Answer: No. The Secret Service does not automatically assign a detail to protect a presidential hopeful until that person has won a major party's nomination.

When President Bartlet was shot on NBC's The West Wing, he did not give up his presidential powers before going into surgery. In reality, must the president transfer power to the vice president in such a situation?

Answer: No, but the power may be taken from him anyway. The 25th Amendment allows for the vice president and ranking members of the Cabinet or Congress to declare the president temporarily unable to discharge the duties of his office. The VP then becomes acting president.

On UPN's Roswell, government agents are trying to uncover aliens living in that New Mexico town. In real life, is the government still investigating the supposed 1947 UFO landing there?

Answer: No. The U.S. Air Force officially closed the case in 1994, concluding that aliens had never invaded Roswell.

In The X-Files on Fox, unsolved FBI cases—usually those dealing with the paranormal—are passed on to the agency's X-Files unit. Does the FBI really have a unit dedicated to paranormal activity?

Answer: No. This one's pure show biz.

|

|