MASH - As It Really Was

Note: The following is an excerpt from a book written by Albert E. Cowdrey. It gives a true life account

of life in MASH units during the Korean War, including comments from Capt. H. Richard

Hornberger (a.k.a Richard Hooker) the author of the M*A*S*H novel.

United States Army in the Korean War -

The Medics' War: Chapter 7 Static Warfare

Life on the Line

The maturing of the medical system took the most varied forms. For

medics in general, comfort and safety in their daily lives improved markedly.

Compared to aidmen, litterbearers, and jeep ambulance drivers who continued to

face danger in their jobs on the line, many medics - especially those in

hospitals - encountered fewer risks. Statistics for 1952 indicated that no

medical officers and only two Medical Service Corps officers were killed in

action. Food was ample, with three hot meals a day served at company

headquarters and battalion aid stations. Most medical companies operated a

PX. Unpleasant duties and heavy manual labor fell to Korean civilians hired

for the task, or to the Korean Service Corps personnel (KSCs). At the MASHs

during late 1951 and 1952 baseball diamonds appeared on level spots,

horseshoes clanged, and volleyball teams practiced. On summer days swimming

parties visited "clear pools formed by mountain streams." As danger lessened,

the surgical hospitals gained a reputation for insouciance bordering on

wackiness. Liquor was abundant and cheap, and the MASH was normally the

farthest point forward that American women got in Korea. Questioned about the

nature of the hijinks during off-duty hours, a MASH doctor later said tersely,

"Oh, sex and liquor. What else is there?"

With such relaxation went, very often, an unmilitary slackness that

reflected both the nature of the war and the outlook of doctor draftees.

Inspections of medical installations in the X Corps during September 1952

showed that poor appearance and absence of spirit were the rule."Mess halls

and kitchens were disorderly and unattractive. Equipment and supplies were

poorly segregated, stored, and maintained. Police was poor. There was no

unit pride. The standards usually expected of medical units and installations

were not, in general, being maintained." The military, as opposed to the

professional, training of the medical officers was "generally poor." Pulled

from budding practices and thrust by their lack of rank to forward stations in

an uninviting land, young doctors displayed unconscious arrogance and a

refusal to adapt to the necessities of a life that they despised. Such men

failed to understand their responsibilities in respect to "equipment,

maintenance, supplies, records, reports, training of enlisted personnel, and

other non-technical activities. A deep sense of responsibility toward the

military service seems never to have been gained."

As a result, even their professional skills sometimes showed poorly, in

part because their enlisted subordinates either did not know or did not

practice their jobs. Enlisted men showed a lack of courtesy, looked

unmilitary, maintained equipment in a slipshod manner, and expected their

failings to be overlooked or condoned. In the X Corps aidmen handled

casualties roughly, leaving them exposed to weather; litterbearers sometimes

ran with patients or walked backward; and drivers operated their ambulances at

excessive speeds. Officers and enlisted men alike were ignorant of or

indifferent to, basic administrative tasks. The corps surgeon blamed the

emphasis on professional and technical subjects to the detriment of field

training. How much complaints of this nature reflected an unbridgeable

difference in style between civilian and military and how much they

represented actual failings on the part of the former is impossible to

determine. Both elements were certainly present.

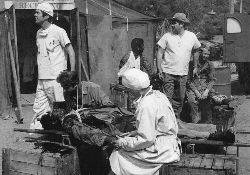

Judged by the only standard that ultimately mattered, the saving of

lives, the draftees did as well as their predecessors. The MASH of 1952 had

become a matured practitioner of emergency medicine in a style that civilian

practice was not to see widely employed for another fifteen to twenty years.

The total system - including attached helicopters, corpsmen to act as

paramedics, and advanced methods of treating shock - was the key to success.

In August 1951 the MASHs had briefly experimented with special shock treatment

sections, only to abandon them because the sections found too little to do

between battles. (Such dedicated units, however, existed in evacuation

hospitals where the staff was larger.) Instead, the MASH's preoperative

section prepared casualties for surgery, acted as a shock treatment unit, and

in slack times ran an outpatient clinic as well.

Amid technical innovations and changes of personnel, one thing that did

not change was the MASH's basic function of performing what Capt. H. Richard

Hornberger of the 8055th later called "meatball surgery." Speaking as Richard

Hooker, pseudonymous author of M*A*S*H, he suggested that

meatball surgery is a specialty in itself. "We are not concerned with the

ultimate reconstruction of the patient. We are concerned only with getting

the kid out of here alive enough for someone else to reconstruct him. Up to a

point we are concerned with fingers, hands, arms and legs, but sometimes we

deliberately sacrifice a leg in order to save a life, if the other wounds are

more important. In fact, now and then we may lose a leg because, if we spent

an extra hour trying to save it, another guy in the pre-op ward could die from

being operated on too late. Our general attitude around here is that we want

to play par surgery. Par is a live patient."

On the operating table "par surgery" did not permit elegant technique. In

suturing the four layers of the bowel, a surgeon from Georgia was not "quite

as dainty" as the replacement he was instructing. "I've got mucosa to mucosa,

submucosa more or less to submucosa, muscularis pretty much to muscularis and

serosa to serosa, and there ain't any place where it's gonna leak. It took

y'all two hours, and it took me twenty minutes." Despite growing stability

and sophistication and a general decline in the proportion of wounded to sick,

brusque and rapid lifesaving technique remained the primary function of the

MASH. When battle wounded flooded in, the ability to work quickly was still

the most basic of skills.

Copyright 1994 Bureau of Electronic Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Main Page