![[safe]](safe.gif)

The Locusts

Kate Capshaw, Vince Vaughn, Jeremy Davies, Ashley Judd,

Paul Rudd, Jessica Capshaw, Daniel Meyer

Directed by John Patrick Kelley

105 mins

![[safe]](safe.gif)

Psst! Quick, someone tell John Patrick Kelley that Tennessee Williams really is dead and buried!

In Kelley's extremely emotionally overwrought tale of darkness and doom in the deep south during the 1960s, every imaginable over-done southern secret is trotted out in routine succession and flogged in all its glorious colour for the audience's delight. All of this makes for a difficult to sit through film which is, in spite of all its flaws, not entirely impossible to stomach. You just need to be in the mood for over-ripe melodrama laden with heavy doses of symbolic touches that all but scream out major plot points.

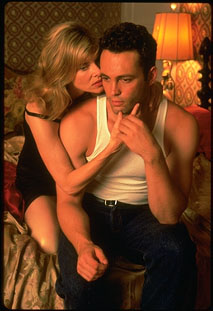

During the hot summer of 1960, Clay (Vince Vaughn), a drifter on his way to California via Kansas hitches a ride into a dead end town, whereupon he immediately catches the fancy of Kitty (Ashley Judd, playing a character only she could consent to play named "Kitty"), a spirited young woman bored with her current paramour, Jim (newcomer Daniel Meyer in a strong debut). The two men slug it out over a macho misunderstanding engendered over Kitty. After the fight is broken up, Clay approaches Earl (Paul Rudd) for job prospects in the vicinity. Goaded on by his girlfriend (Jessica Capshaw - yes, she is Kate's daughter), Earl agrees to recommend Clay to feedlot owner Delilah Potts (Kate Capshaw - what a character name!), for work on her estate, Ashford, which belonged to her long dead daddy. When Clay meets Delilah, tensions rise as she makes it clear that he is more than an employee, less than a guest. Unwilling to believe that he's a simple drifter, she continually invites him to her table, intending to seduce and discard him as she has done over the years with all of her farm-hands (you can tell this script was written by a man). Instead of appreciating her charms, Clay becomes fascinated by Flyboy (Jeremy Davies), Delilah's deathly silent son who skulks about the kitchen, speaking only to his pet bull. When Clay realises that Flyboy was institutionalised upon seeing his dead father hanging from a tree

During the hot summer of 1960, Clay (Vince Vaughn), a drifter on his way to California via Kansas hitches a ride into a dead end town, whereupon he immediately catches the fancy of Kitty (Ashley Judd, playing a character only she could consent to play named "Kitty"), a spirited young woman bored with her current paramour, Jim (newcomer Daniel Meyer in a strong debut). The two men slug it out over a macho misunderstanding engendered over Kitty. After the fight is broken up, Clay approaches Earl (Paul Rudd) for job prospects in the vicinity. Goaded on by his girlfriend (Jessica Capshaw - yes, she is Kate's daughter), Earl agrees to recommend Clay to feedlot owner Delilah Potts (Kate Capshaw - what a character name!), for work on her estate, Ashford, which belonged to her long dead daddy. When Clay meets Delilah, tensions rise as she makes it clear that he is more than an employee, less than a guest. Unwilling to believe that he's a simple drifter, she continually invites him to her table, intending to seduce and discard him as she has done over the years with all of her farm-hands (you can tell this script was written by a man). Instead of appreciating her charms, Clay becomes fascinated by Flyboy (Jeremy Davies), Delilah's deathly silent son who skulks about the kitchen, speaking only to his pet bull. When Clay realises that Flyboy was institutionalised upon seeing his dead father hanging from a tree  (apparently after catching Delilah in bed with another man), and that since his release he's been a virtual prisoner in the house, shunned by the other farm workers, he resolves to befriend and free the young man. Together with Kitty, who's fallen in love with him, he manages to convince Flyboy to assert his independence, to disastrous results. Delilah, in a fit of rage, castrates Flyboy's pet bull, thereby emasculating him, rendering him forever fearful of her. Incensed at her behaviour, Clay decides to leave with Flyboy. He reveals his true identity to Kitty: an ex-lifeguard who's wanted for the suspected rape and murder of a young girl in the neighbouring city, but she decides to help him escape. Alas, Delilah also knows his secret, and uses it to enslave him sexually, knowing that they will again be caught by her son. True enough, when Flyboy realises that his friend has "betrayed" him, he drowns himself. An anguished Clay discovers his body. Whilst Earl and Kitty try to comfort him, Mrs Potts kills herself, thereby ending the family cycle of violence and madness. Finally, Kitty and Clay leave Ashford behind, on the run from the authorities.

(apparently after catching Delilah in bed with another man), and that since his release he's been a virtual prisoner in the house, shunned by the other farm workers, he resolves to befriend and free the young man. Together with Kitty, who's fallen in love with him, he manages to convince Flyboy to assert his independence, to disastrous results. Delilah, in a fit of rage, castrates Flyboy's pet bull, thereby emasculating him, rendering him forever fearful of her. Incensed at her behaviour, Clay decides to leave with Flyboy. He reveals his true identity to Kitty: an ex-lifeguard who's wanted for the suspected rape and murder of a young girl in the neighbouring city, but she decides to help him escape. Alas, Delilah also knows his secret, and uses it to enslave him sexually, knowing that they will again be caught by her son. True enough, when Flyboy realises that his friend has "betrayed" him, he drowns himself. An anguished Clay discovers his body. Whilst Earl and Kitty try to comfort him, Mrs Potts kills herself, thereby ending the family cycle of violence and madness. Finally, Kitty and Clay leave Ashford behind, on the run from the authorities.

From the above plot summary, it is evident that John Patrick Kelley is a keen observer of long hot summers and one too many Tennessee Williams plays. His script is quaintly fashioned, premised as it is on a whole list of supposedly deep dark secrets that will rend apart the familial relationships that are already asunder at the heart of his story. His characters consist of over-sexed coquettish young women, black widows with a vengeful past, idealistic idiot-innocent martyrs and mysterious strangers with their own shameful secrets. These are the types of characters that one would have thought had long over-stayed their welcome in the films of today - obviously, Kelley disagrees. Here, he dutifully dredges up every old trick in the book, complete with long angled shots that frame the estate as a prison and a haven for Clay and the other men who work there, and he lovingly frames Mrs Potts at the centre of it all, the enigmatically bitter and cruel predator who holds all their futures in her hand. His style is heavy-handed, with many metaphorical dialogue touches involving locusts and their mating rituals, and all his characters speak with a passionate belief and conviction which sounds unrealistic, if suitably deranged, given their sad sorry existence. As a director, Kelley fares much better.

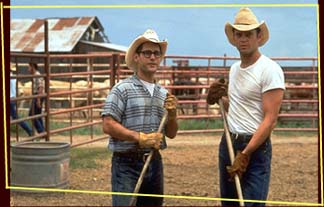

Vince Vaughn, hot ever since "Swingers", assays a different kind of role here. Sweaty and strong, he plays Clay as an old-fashioned man, one on a power-trip who thinks he can undo several lifetimes of evil by freeing Flyboy. To his credit, Vaughn never seems to realise how badly written his character is, and his performance is authentic and convincing, simply because he believes in the material he has to work with. At times menacing and broody (when he's dealing with Mrs Potts and Jim), and yet tender-hearted and kind toward Flyboy, Vaughn's Clay comes across as a real human being, full of contradictions and inexplicable motivations. It is to his credit that audiences do not screech with amusement whenever Clay starts to spout  leaden dialogue which is laughably bad. In contrast to his physically imposing presence, Jeremy Davies creates a mere slip of a character which dominates the film through his silence and eerie features. This is Davies' second outing this year as an introverted outsider (previously seen in "Going All the Way" with Ben Affleck). With the aid of ticks and mannerisms this time, he creates a character that is all mystery and fear. It is one of those performances which critics will sit up to take note of simply because it is so striking. However, you never once get the feeling that Flyboy is possibly a real human being (which is as much the writer's fault as it is the actor's) - you just feel that Davies is an exceptionally gifted actor who could do much better work if he'd stop playing these tormented creatures and smile for a change. That said, he does convey the pain and confusion that Flyboy feels very well, and plays off Vaughn very effectively.

leaden dialogue which is laughably bad. In contrast to his physically imposing presence, Jeremy Davies creates a mere slip of a character which dominates the film through his silence and eerie features. This is Davies' second outing this year as an introverted outsider (previously seen in "Going All the Way" with Ben Affleck). With the aid of ticks and mannerisms this time, he creates a character that is all mystery and fear. It is one of those performances which critics will sit up to take note of simply because it is so striking. However, you never once get the feeling that Flyboy is possibly a real human being (which is as much the writer's fault as it is the actor's) - you just feel that Davies is an exceptionally gifted actor who could do much better work if he'd stop playing these tormented creatures and smile for a change. That said, he does convey the pain and confusion that Flyboy feels very well, and plays off Vaughn very effectively.

In the most thankless roles written for the film, Ashley Judd and Daniel Meyer perform admirably well. One wonders what it was that attracted Judd to the film, since it does not cover any interesting ground for her as an actress. Nonetheless, she adds many moments of spark to the film - that's movie-star quality for you. Meyer plays a bad guy who's despicable and low, but he is at least allowed one scene to break out from this stock characterisation, and to his credit, he does his best with it. As for Paul Rudd and Jessica Capshaw, after the initial minutes, their characters are mere window-dressing to the plot, totally superfluous to the proceedings. It was cute that they both seem to be wearing identical "geek" spectacles, although Rudd's affectation of a limp for Earl served no particular purpose. Furthermore, his exact relationship with Mrs Potts is never clarified, although the way the roles were played, you got the impression that there was a lot more going on there than the film let on.

Moody and surprisingly engrossing despite its absurdly out-dated script elements, "The Locusts" suggests that Kelley is a promising film-maker. He should have waited for better material to try his hand. As it is, this is one very torrid film that recalls "Suddenly Last Summer", lobotomy plot and all. It is a pity to watch a whole host of talented people waste their time and effort on something so slight as this. Kelley's flair for framing his film (this is one of the most effectively shot dramatic debuts I have ever seen) and his strong direction of the actors suggests that he is capable of something much much better than this sub-standard retread of un-original territory. Whilst not an entire non-event, one hopes that "The Locusts" is a mere starting point for its writer-director to go on and make something to really wow us in the future.