The boy's parents are wealthy British citizens who enjoy great luxury in Shanghai, a life in which limousines hurry them through the crowded streets to business meetings and masquerade balls and they hardly need notice the ordinary people in those streets. Sometimes the Chinese press too close to the car, sometimes they hold up traffic, but mostly they are simply invisible-- until war breaks out, and the boy's whole world is shattered.

The most agonizing moment in Steven Spielberg's "Empire of the Sun" comes near the beginning as the streets of Shanghai are filled with a panic-stricken mob and he is separated from his parents as they flee to sanctuary. One moment his mother has him by the hand, and the next moment he has dropped his toy airplane and stooped to pick it up and they are separated by 5,000 frightened people, never to see each other again until the war is over.

The boy is lost, left behind and finally placed in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. His story is based on the autobiographical novel by J. G. Ballard, who lived through a similar experience as an adolescent. But if Ballard had not written his novel Spielberg might have been forced to, because the story is so close to his heart. Not only do we have the familiar Spielberg theme of a child searching for his parents, but we also have the motif of the magic above reality-- the escape mechanism into a more perfect world, a world that may be represented by visitors from another planet, or time travel, or hidden treasure. This time, it is the world of the air-- and airplanes.

Life on Earth is not so enjoyable for the boy, whose name is Jim, and who is played by Christian Bale with a kind of grim poetry that suggests a young Tom Courtenay. There are no free passes for kids in the prison camp, and Jim soon finds a protector of sorts in Basie, an American prisoner played by John Malkovich with a laconic cynicism. Basie is a merchant seaman and born hustler, and his corner of the prison camp is a miraculous source for Hershey bars and other contraband (in his resourcefulness and capitalistic zeal, he's a reminder of the William Holden character in "Stalag 17"). Basie doesn't exactly play father to the kid; he permits him to exist in his sphere and to survive.

Jim is a quick learner. Short, fast and somewhat invisible because of his youth, he has the run of the camp. He knows all the shortcuts and all the scams and steals to survive. He also dreams of airplanes, and as the months go by, he dreams less frequently of his parents and finally cannot quite even remember their faces. Spielberg portrays the prison camp as another of those typically Hollywood enclosures where the jailers embody cruel authority while somehow permitting the heroes to raise hell and have a relatively good time. Like the adolescent in John Boorman's recent "Hope and Glory," Jim finds that young boys can even enjoy war, up to a point.

The movie is always interesting from a narrative point of view. Spielberg is a good storyteller with a good tale to tell. But it never really adds up to anything. What statement does Spielberg want to make about Jim, if any? That dreams are important? That survival is a virtue? The movie falls into the trap of so many war stories, and turns horror into nostalgia. The process is a familiar one. War experiences are brutal, painful and tragic, but sometimes they call up the best in human beings. And after the war is over, the survivors eventually began to yearn for that time when they surpassed themselves, when during better and worse they lived at their peak.

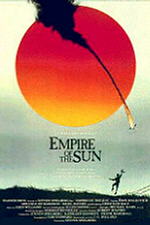

The movie is wonderfully staged and shot, and the prison camp looks and feels like a real place. But Spielberg allows the airplanes, the sun and the magical yearning to get in his way. Jim has a relationship, at a distance, with a young Asian boy who lives outside the prison fence, and this friendship ends in a scene that is painfully calculated and manipulative. There is another moment, at about the same time in the film, where Jim creeps outside the camp by hiding in a drainage canal and escapes capture and instant death not because of his wits but because Spielberg forces a camera angle-- placing his camera so that a person cannot be seen who would be visible in real life. And there is the inevitable moment when the boy is associated with a huge telephoto image of the sun, and we respond not to the shot but to the memory that Spielberg loves huge celestial orbs so passionately that Jim isn't having a spontaneous moment, he's paying homage to the sun of "The Color Purple" and the moon of "E.T."

The movie's general lack of direction leads to what seems like a series of possible endings; having little clear idea of where he was going, Spielberg isn't sure if he has arrived there. The movie's weakness is a lack of a strong narrative pull from beginning to end. The whole central section is basically just episodic daily prison life and the dreams of the boy. "Empire of the Sun" adds up to a promising idea, a carefully observed production and some interesting performances. But despite the emotional potential in the story, it didn't much move me. Maybe, like the kid, I decided that no world where you can play with airplanes can be all that bad.