The key driving creative elements that formed the long evolutionary process of the Cinema were: Communication, Artistic Expression, Entertainment and – ultimately - Commercialism. Beings have always needed to communicate with one another from the earliest times of humanity’s history. In these primitive times, torches and lanterns accomplished an immediate form of communication over long distances. Illustrations rendered on cave walls told a story of everyday life to later generations. The more accurate the illustrations, the more communicative these renderings were. In the Painted Cave of the Caves of Altamira, Spain is a rendering of a bison. This bison is depicted with eight legs. This is not some sort of ‘freak of nature.’ It is a prehistoric artist’s attempt to depict movement through a still image, the first to ever do so. Storytellers developed the need to illustrate their tales. As civilization developed, the need to communicate and relate stories became more important as well as more complex. Principles of light and projection gave rise to the development and usage of Magic Lanterns. At first, the projected images were drawings, and then photographs ‘gleaned from life.’ Mechanical elements, independently developed, combined to produce the first motion picture devices. These devices were demonstrated and offered as entertainment on several occasions. Occasionally, the curious were charged a nominal entrance fee for the privilege to view ‘pictures that moved.’ Few, if any, saw a commercial future for it. None could imagine what it could eventually grow to become.

Of these few, two creative artists were inspired enough by what they were witnessing to attempt to take the element of mere ‘pictures that move’ ahead to the next step of development. This next step would prove to be a quantum leap forward.

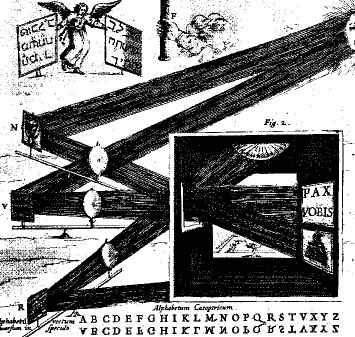

One could not attempt to determine what element of the development of the Motion Picture would be more important, technical or artistic advancement. Cinema history has proven that the two entities go hand-in-hand. The technician provides the physical means for the creative artist to utilize. The creative artist in turn uses whatever means at his disposal to define his art, occasionally creating a need for improved tools and materials. Motion Pictures can more accurately be termed an art form. The metamorphosis of what would eventually become the disjointed history of the Cinema drew from several histories of diversely related elements. These include illumination and projection methods, photography, theater arts and the mechanics of movement. This long development of cinematography spans many centuries. The process involved many innovators and improvements on earlier related devices. As far back as 125 AD, Heron of Alexandra wrote descriptions of something he described as ‘mirror writing.’ In 150 AD the first ever description of an ‘after-image’ effect, in connection with vision, was written in a Latin translation (from the original Arabic) of Optica by Claudius Ptolemy. The premier description of the principle of the camera obscura was written by Ibn al Haitam (also known as Alhazen) (d 1038) in (ca) 1030s. Early contributions can even be credited to Gallileo and his experimentation with lenses as well as Leonardo DaVinci who studied the camera obscura and observed the persistence of vision. The ancient ‘shadow plays’ of China, India and Java can also be included in this long developmental process. Throughout the late middle ages the magic lantern began making appearances. In 1646 a Jesuit priest named Athanasius Kircher (1601-1680) claimed to be the ‘inventor’ of the magic lantern in his book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae. Yet closer examinations of the illustrations in his book reveal that what he claims as his own is simply a bungled depiction of someone else’s earlier device. Such dubious claims and outright plagiarisms were constant throughout history, a practice which continues into modern times.

Select audiences at the turn of the century, from the 1700s to the 1800s, witnessed a magical and popular form of entertainment. Magic lanterns were getting more sophisticated, in both technical aspects and subject matter. Lenses were more efficient as well as were stronger light sources used in projection. The earliest slides used for these shows were intricately painted illustrations on a translucent material. This material eventually gave way to glass. These hand renderings eventually became photographic images. The most successful and popular of these magic lantern shows was the Phantasmagoria. Belgian Etienne Gaspard Robertson (1763-1837) fashioned an evening’s entertainment with projected illustrations of ghosts, skeletons and all forms of fantastic imagery. Since the newly developed equipment was relatively lightweight and portable, the Phantasmagoria enjoyed many tours throughout Europe. Needless to say, imitative shows cropped up, even in the USA. Magic lantern showings were also being adapted into stage shows. It was a matter of time before enterprising individuals began to experiment with projection technology and embellish it with some form of rudimentary movement.

Many early magic lantern slide combination apparatuses contained some form of rudimentary form of movement. This usually involved a simple two-stage process. These particular slide transparencies consisted of two pieces of material sandwiched together. The lantern operator would manually operate one slide on top of another slide. Since two separate, yet related images, were contained on the slides, the effect in the projected image was one of apparent movement. The subject matters were very simple, ie, a ship at sea rocking on the waves, a horse in two stages of movement, bicyclers, faces changing expressions, a man asleep in bed with a rat leaping into his open mouth, etc. Before long, complete stories were being presented via magic lantern. These stories covered everything from well-known fairy tales to the ever-popular Passion Play. Concurrent with the experimentation, development and exploitation of the magic lantern was the appearances of the many optical toys. Utilizing the ‘phenomenon’ of the persistence of vision, devices such as the Thaumatrope (1825), the Phenakistiscope (1832), the Zoetrope (1834) and the Praxinascope (1877) appeared and were popular. All allowed essentially one or two viewers to view synthesized movement. To this day, these optical toys are being marketed in one form or the other. Utilizing principles of slide projection and the Praxinascope, Emile Raynard (1844-1918) developed a rudimentary, yet popular, form of early motion picture entertainment that he called Le Theatre Optique in 1888. With this system small groups of people were able to view a projected form of synthesized movement. What was needed to be accomplished next was an amicable marriage of the technical and the artistic.

By the mid 1800s, in various places and independent of each other, artists and photographers were studying animal and human locomotion. These men were also studying and improving upon the work of others. Up to this time photographic images were made first with metal and eventually glass as a base. Sensitized paper was experimented with to some degree of success but was not able to withstand the stress of movement within these embryonic motion picture devices. A way of improving upon the mechanics of devices, such as the Zoetrope, was achieved in 1853 by Uchatius (1811-1881). Edweard Muybridge’s (1830-1904) experiments in 1877 involved the use of 24 separate still cameras to photographically record 24 separate successive stages of movement. This later prompted the standard motion picture running time of 24 frames per second yet currently in use. Jules-Etienne Marey (1830-1904) in 1882 devised a camera shaped like a shotgun for photographing a series of still images. To this day the term ‘shooting film’ is still in popular usage. By 1884 a brighter, clearer and steadier system for projection was devised by Ottomar Anschutz (1846-1907). So went the natural progression of the development of cinematography.

In France, Louis Aime Augustin LePrince (1842-1890) accomplished the first successful photographic recording and projection of true ‘moving pictures.’ Utilizing chemically sensitized paper, he recorded a series of images, in successive stages of movement, of traffic crossing Leeds Bridge in October of 1888. Unfortunately he was not able to continue his experiments. LePrince’s work and mysterious disappearance are the subjects of a book and ‘mockumentary’ titled THE MISSING REEL (1990). In England another dedicated experimenter, William Friese-Greene (1855-1921), was working to develop a moving picture device at approximately the same time. His story, also tragic, is told in the book and feature film titled THE MAGIC BOX (1951). Friese-Greene’s grave marking in Highgate Cemetery (north of London, England) bears the inscription, 'The inventor of Kinematography. His genius bestowed upon humanity the boom of commercial kinematography of which he was the first inventor and patentee. (June 21st, 1889, No 10,301).’ This is possibly the only grave epitaph that includes a patent date and number. If LePrince’s burial had ever been documented, his marker surely would have bore a similar epitaph. Two men working in the USA without knowledge of each other around 1887, Rev Hannibal Goodwin (1822-1900) and George Eastman (1854-1932), invented the material called celluloid. Sources credit Goodwin with first developing the raw material with Eastman soon after refining it and making it available for photographic purposes. The mass production of this material became tantamount in the further advances of the development of cinematography.

As early as 1877 Thomas Edison conceived of a device that would, ‘do for the eye what the phonograph did for the ear.’ Called the ‘optical phonograph’ (did he see the future video disc and compact disc?), these early contrivances resembled a flat disc approximately 8 to 10 inches in diameter - a little larger than a 78 rpm record. Cut into a single side of the disc was a continual spiral forming rows of concentric circles. These were both grooves of sound and complimentary miniature images of matching successive stages of movement. The audio portion was played back via the conventional phonograph needle method. The images were viewed through a microscope-like device. The few ‘optical phonographs’ that were ‘cut’ were usually of a single voice singing (or, more appropriately ‘squawking’) a popular tune. The image was of the singer moving about and waving his or her arms. The sound quality was muffled and the image, though it managed to display a rudimentary synthesis of movement, was shaky and blurred. They were unsuccessful, but experimentation continued. This was done generally by others in Edison’s employ. By 1888 Edison’s first cine camera was demonstrated. In 1891, he set about to introduce to the world the ultimate motion picture device. By this time, his concept was for a viewing device where a single viewer would pay a nickel to see a few minutes’ of cinematic action. These devices, known as Kinetoscopes, were commercially exploited in what ultimately became known as Nickleodeons. Other establishments containing these devices opened and were named Kinetoscope Parlors. Soon they became popular in the major cities of the USA and eventually throughout Europe. This all was happening before 1894. Projecting images to a group of people was not how Edison saw the future of what would become The Movies. Eventually his vision changed. However, it took the efforts of others to initiate that change.

Accepting an assignment from Edison, his boss, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson (1860-1953) set about to hone and perfect the cine camera. He combined his talent with two others who were working on similar devices independently; Major Woodville Latham (1838-1911) and Thomas Armat (1866-1948). Latham determined that for the film to easily move past the film gate it needed to be looped above it…thus the ‘Latham Loop.’ Armat developed a maltese cross-styled pull-down claw mechanism for advancing the film. The combination of both innovations produced a smooth mechanical technique of intermittent movement, the movement of moving pictures. Edison managed to make a few personal contributions to all of this. He established the film’s width, or gauge, to be 35mm and for four sets of sprocket holes, or perforations, per individual frame of image. These are the standard in use today. The resultant machine was called the Vitascope. Soon after, it was rechristened the Kinetoscope. Making appearances at expositions, its popularity became worldwide. This Kinetoscope caught the attention of the Lumieres in France. Dickson, with his sister Antonia, published a monograph titled History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kineto-Photograph in 1895. Reprints have appeared in 1984 and in 2000. This work is the first published history of early motion picture devices. Consequently, the Dicksons became the world’s first Cinema Historians.