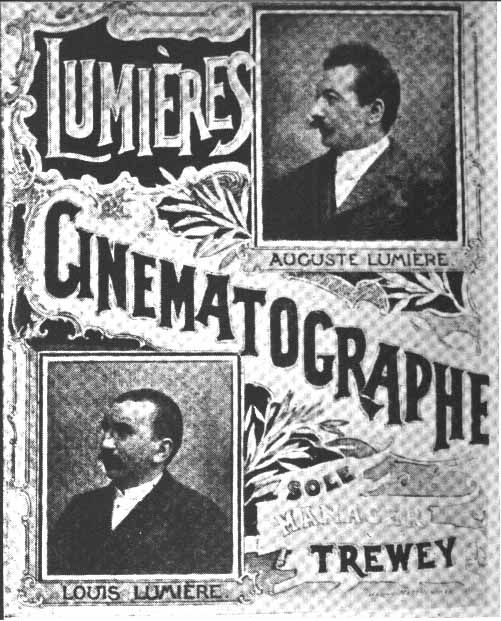

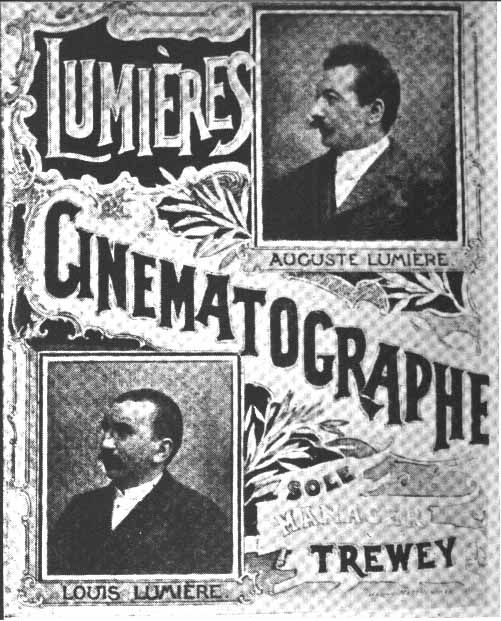

Louis (1864 – 1948) and Auguste (1862 – 1954) Lumiere had the advantage of being born into a family active in the arts. Their father Antoine’s (1840 – 19?) training was originally as a painter but then became interested in photography. He was active as a photographer in Besancon, France, where his sons were born. He moved to Lyon in 1871 and ten years later opened a factory for photographic products in Lyon-Montplaisir. Louis and Auguste joined the family enterprise when they were old enough. Louis, a trained physicist by age 17, invented a dry plate photographic process. This caused the business to prosper and eventually become a major industry by 1883. Throughout the 1880s and early 1890s he continued to make refinements in this process. In 1893 Antoine retired. Auguste became involved in the business aspect of the factory. Their introduction to the entity of ‘pictures that move’ happened at the Paris Exposition of 1894. One of the wonders on display was a demonstration of the Edison Kinetoscope.

The Kinetoscopic images were viewed from a single vantage point, displayed in a peep show apparatus. One person at a time viewed the action, which lasted no more than a minute. This was accomplished by looking down into a shielded viewer while turning a handle on the side of the device. Antoine purchased one of these machines for 6000 francs (app $1225). This fired the brothers’ imaginations. Immediately they set to work developing a similar yet improved device. One innovation was to create a motion picture apparatus that would serve a dual purpose: record images on a strip of film as well as project them on to a screen. This way more than one person at a time could view the action. The Edison standard of utilizing a perforated filmstrip was retained. A major change of the Lumieres was an eccentrically driven moving claw for moving the filmstrip. This improved mechanical performance and created a steadier image. This particular element has changed very little to this day. Over a period of almost year and a half other specific changes were made, based on the earlier devices of other contemporary experimenters. Another important improvement was in the new device being more lightweight and portable than Edison’s. Auguste always liked to tell the story that the final working machine came to him in a single night, in a ‘flash of inspiration;’ “A night, moreover, during which I was suffering from feverish dreams and migraine.”

This ‘invention of a single night’ camera and projector contained in a single apparatus was patented on February 13, 1895 (Number 245,032). Its special characteristic was expressed in its name: Kinetoscope de (en) projection. The gauge of the film of this new device was closer to 80mm, more than twice the 35mm width of Edison’s camera. In leaps and bounds, culminating from the work of many, the Cinema was coming into existence. The Lumieres’ device was christened with yet a new name: the Cinematographe. On March 22, 1895, at the rue de Rennes 44 in Paris they presented their first film production to the Societe d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale. Presented was LA SORTIE DES OUVRIERS DE L’URSINE LUMIERE (WORKERS LEAVING THE LUMIERE FACTORY). Three versions of this particular film were produced, on three different occasions. The program was enlarged to eight short films and by June 10, 1895 another showing was presented to the congress of the Societies Photographiques de France in the great hall of the Palais de la Bourse in Lyons.(8) Demonstrations continued in Brussels on June 10, July 11 and November 10. On November 16 a demonstration occurred in the Sorbonne. All presentations were put on for audiences of invited specialists. The next logical step was to lease commercial room space and offer public showings-to paying audiences.

The 19th century was quickly coming to an end, propelled by the powers of electricity and steam. In Paris, France, appropriately referred to as ‘The City of Light,’ a new kind of ‘light show’ was open to the public. On December 28, 1895 in a back room setup of the Salon Indien of the Grand Café on the Boulevard des Capucines 14 the first public performance of the Lumieres’ Cinematographe took place. Here was the absolute first time that such entertainment fare was offered to a paying audience on a regular basis. Word of mouth spread. Unlike the earlier form of magic lantern shows, these images were not merely still images of subjects ranging from the mundane to the exotic. The images in this new exposition moved, apparently with a life all their own. In varying shades of gray were street scenes bustling with activity, people at work at their daily jobs, parents feeding a baby and other slices of everyday life. Technically, the subject matter of these first film programs could be considered documentary in nature and not narrative. Another brother, Antoine, was present at these particular showings as Louis and Auguste had more pressing things to do. Admission was one franc. Opening day netted thirty-five francs. In a very short time the showings were taking in 300 francs per day. Since no advertising space was bought in the newspapers, the media of the day was reluctant to report the event. However, later reports were enthusiastic.

All of the programs presented to the previous ‘invitation only’ audiences were included in these premiere public shows. The projected sequences consisted of single filmstrips shown with no topical connection to each other. Two particular titles proved to be very popular and much talked about: L’ARRIVEE D’UN TRAIN EN GARE and L’ARROSEUR ARROSE (THE ARRIVAL OF THE TRAIN AT THE STATION and WATERING THE GARDENER). In the first sequence a train was viewed in the distance and then roaring in to a close-up as it arrived at the Gare de Lyon. This almost always caused a thrill with these early Cinema patrons who reacted to this on-screen action by gasping and averting their eyes. On the screen as the train passengers exited, one could be seen glancing toward the audience almost as if to say, “Don’t be alarmed, all is well.” Something was assuredly magical about the passé sight of passengers departing from a train at a station. The second scene was the first example of cinematic farce. A man is shown watering his garden. In view of the audience, but not the gardener, a boy pinches the hose. The water stops and the gardener peers into the nozzle. The boy releases the hose causing the gardener to get a face full of water. He then chases the boy, catches and spanks him. With this brief film program the subject matter moved into the realm of rudimentary storytelling. However, instead of displaying an action caught on film as it was actually happening, a specific activity was staged. Since that activity is a simple incident, it could not be considered a true narrative. Posters advertising the Lumiere screenings at this time depict amused audiences enjoying L’ARROUSEUR ARROSE pictured on the screen. These affiches are generally regarded as the first cinema posters ever. The simple, but effective, gag of ‘watering the gardener’ has resurfaced throughout cinema history, turning up in short films ranging from The Three Stooges to Our Gang comedies.

The Lumieres assuredly saw the Cinematographe’s potential as a money making venture…but only for the here and now. They did not see it as any sort of art form that would blossom, endure and grow beyond the 19th Century. Nor did they see the technology develop beyond where it was at the present. Possibly, they felt that some other form of ‘higher tech’ temporary entertainment would soon replace it. However, a company was formed, camera crews were hired and sent to far away places around the world. Cinematic snippets of the average activities of people in other lands were amassed to serve as program material for their shows. In April 1896 the Cinematographe was demonstrated in Vienna to Emperor Franz Josef, June 12 to the Queen of Spain, June 25 to the King of Serbia, on July 7 and 25 to the Tsar and Tsarina of Russia. Royalty approved and were greatly entertained with this new entity of ‘pictures that move.’ This was in an age where approval by royalty was a supreme endorsement. Within the first few months of this same year Cinematographe theaters were opened in Lyon (on January 25), in London (on February 17), in Bordeaux (on February 18), in Brussels (on February 29) in Berlin (on April 30) and eventually in New York (on June 18). The New York Cinematographe Theater opening was in less than two months after the opening of the Vitascope at the Koster and Bial’s Music Hall on 34th Street.

In 1897 their first catalogue, the first ever ‘film catalogue,’ appeared, printed by Decleris et Fils in Lyons. 358 different filmstrip titles were listed. These averaged seventeen metres in length, running times being a mere few seconds. Subjects were listed under various headings: Vues generales, Vues comiques, France, Algerie, Tunise, Allemagne, Angleterre, Espagne, Autriche-Hongrie, Russie, Suisse and Amerique du Nord. Under these subjects were documentations of actual events. The program of Germany contained scenes of the Panoptikum in Fredrichstrass and the Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. Three sequences covered the UNVEILING OF THE MONUMENT TO WILLIAM I: 1- ‘Before the Unveiling,’ 2- ‘The Unveiling,’ 3- ‘Parade of the Hussars before William II;’ then ‘William II and Nicholas II on horseback;’ finally pictures of Cologne, Dresden, Frankfort am Main, Hamburg, Munich and Stuttgart. This first catalogue contained essentially documentary films. They displayed cultural events and even brief story subjects. These first stories were merely snippets of longer, popular stories rather than programs prepared to utilize the film medium. Rudimentary experimentation with cinematic special effects occurred with titles such as DEMOLITION DE UN MUR I – II. A wall is shown being demolished and then magically reconstructed. This was accomplished by a simple showing of the film first forward, and then in reverse.

By 1898 no less than six more catalogues had appeared. A combined total of one thousand titles were listed. The list now included more involved historical and literary sequence reconstructions, with longer running times: a FAUST in two parts, a LIFE AND PASSION OF JESUS CHRIST as well as films about Nero and Napoleon. It must be emphasized that these earliest films were not complete programs containing a beginning, a middle and an end, but rather short sequences of longer established works. A Catalogue general of 1901 listed 1299 titles. All the elements of blossoming into an industry were present, in spite of what the Lumieres’ originally predicted. To the French, the Lumieres were considered the genuine inventors of the Cinematographe. Even though earlier innovators developed many of the elements of their invention, theirs was now the standard machine in use. Unlike Edison (who they were compared with) in the USA, they did not establish a laboratory staffed by talented craftsmen and engineers working toward particular goals. Rather, they had an already established laboratory they preferred returning to. Subsequent inventions ran from the improved versions of the Cinematographe to a prosthetic hand for the wounded of WWI. When other entrepreneurs offered to purchase the rights to the Cinematographe, the Lumieres flatly turned them down. Thomas, the Director of the Musee Grevin offered 20,000 francs and Lallemand, Director of the Follies Bergere offered 50,000 francs.

Between 1898 and 1900 Louis Lumiere developed a process for wide screen projection to be unveiled at the Paris Exposition. It projected onto a screen 21 meters by 16 meters. On December 29, 1900 he was granted a patent for a system for stereoscopic cinema. However, his first stereoscopic films were not made until 1936. In 1902 a patent was granted for a method for producing a static circular photograph called the Photorama. In 1905 the last films were made for the Societe Lumiere. They then ceased operations. He abandoned his position with the Lumiere factory in 1920. By now a thriving worldwide Cinema industry was well under way. On December 28, 1945 a ceremony honoring the 50th anniversary of the Lumieres and their premier film screenings was held at 14 Boulevard des Capucines. Now retail stores, the former site of the Café Indien was embellished with two wall plaques. One plaque honors the Lumieres. The second mentions an ‘hommage des professionnels to Reynaud, Marey, Demeny, Lumiere et Melies, Pioneers du Cinema.’ Both brothers were part of the honoring. In 1995 a celebration to honor the centennial of the Lumieres’ premier film shows was held. This happened as part of a festival on and around the property owned by the Lumiere family in Lyon-Montplaisir. Some of their early film programs were restaged. Utilizing original equipment and film stock, a select gathering of people from the contemporary film industry was photographed emerging from the main doors of the still standing Lumiere factory. This was a reenactment the LA SORTIE DES OUVRIERS DE L’URSINE LUMIERE (WORKERS LEAVING THE LUMIERE FACTORY) of 1895.

The Lumieres rest in the family plot in the Cemetiere de la Guillotiere, in Lyon.