Wild

in the City

By Claire Martin

(from the Denver Post Empire Magazine, December 28, 1997)

What Wendy Shattil saw in the

cemetery one spring day was a reversal of the ancient line from

"The Book of Common Prayer": In the midst of death, she

found life.

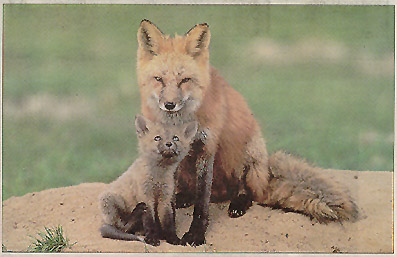

Shattil was visiting her grandmother's grave, cleaning away

debris. As she tidied the grave site, she thought she saw

something prance about 100 yards away. She looked again, and saw

a red fox playing with a couple of young kits.

She smiled and wondered what her late grandmother would have

thought of the sight. Perhaps she would have said that it

perfectly captured the last years of their relationship.

Before she died, at age 100, Matilda Solomon often complained

that her granddaughter's wildlife photography business meant that

Shattil spent more time with wild animals than she did visiting

Solomon. But she also loved the stories Shattil told about her

adventures in the field.

And now, here was another adventure, right beside her

grandmother's final resting place. Shattil was back, with her

cameras, the next day.

And the next day. And the next. For nearly four years, she went

to the cemetery. Somewhere, she thought, her grandmother was

smiling, appreciating the irony: Finally, Wendy found a way to

combine visits with wildlife photography.

"I visited my grandmother's grave, and the foxes,

religiously for months," Shattil said. (She withholds the

cemetery's name, worried that the foxes might be harassed.)

It was one of the few times she's done a solo photo project, and

the first book she's done on her own. Usually, she and her

partner, wildlife photographer Bob Rozinski, work so closely as a

team that they share the credit line on the photographs they sell

to nature and conservation magazines - National Wildlife,

Audubon, National Geographic, Ranger Rick, Natural History - and

Sierra Club calendars.

And they initially shared the credit line on the photo that won

the prestigious international BBC Wildlife competition in 1990.

Then the BBC called the Shattil/Rozinski office.

"Bob answered the phone, and they said, 'We must know which

of you took this picture,' and he said, 'Oh, well, it's Wendy's,'

and then we found out it was the grand-prize winner, which they

were not about to give to two people," Shattil said.

The grand-prize winner, as it happens, was a picture of an

intent, clear-eyed fox - not one of the foxes from the cemetery -

surrounded by grass and wild-flowers.

"It's odd, what foxes do to us," Shattil said.

When she first began photographing the cemetery foxes four years

ago, Shattil figured she'd use the results in a magazine, as a

photo-essay about her grandmother. The fox project seemed somehow

personal, a kind of tacit pact that had as much to do with

Shattil's grandmother as it did with the foxes. She never thought

her photographs and journal would become a book.

"If I had," Shattil said, "Bob and I would have

done the project together."

Instead, "City Foxes" (Denver Museum of Natural

History/Alaska Northwest Books) became Shattil's second solo

book. Susan J. Tweit's text is drawn from the journals Shattil

kept as she was photographing the foxes.

During the years she photographed the cemetery foxes, Shattil

drove her truck to the cemetery every morning and afternoon for

several months a year. She sat in the truck for two or three

hours at a time, lens balanced on the open window. She got to

know the groundskeepers and the regulars who came through the

cemetery. Besides the people who came to visit graves or drop off

flowers, there were picnickers and joggers, dog-walkers and

strollers. One groundskeeper deliberately walked by the fox den

on his daily rounds to make sure the family was OK and that the

dog-walkers weren't letting their pets run amok. Sometimes

drivers in funeral processions noticed Shattil keeping vigil and

paused to see what was so interesting. If they saw the foxes,

often they'd stop to watch, too.

The best fox-watching days began when the kits first began

venturing out of the den, when they were about 6 weeks old.

Before that, Shattil would see the male fox trotting in and out

of the den. When the female, looking haggard, finally emerged,

Shattil knew that before long, the babies would follow. At first,

the kits cautiously poked only their heads above ground. Fluffy

with gray-black baby fur, they peered around curiously and a

little myopically. Dazzled by the bright daylight and unnerved by

the vast world, they stayed close to their mother.

Later, as the kits grew braver, they played games that looked a

lot like chase and hide-and-seek. They pretended to fight,

attacking one another's faces and necks with their sharp little

teeth. They pounced on prey, real and imagined, hunting bugs and

snapping at the carcasses of small birds and animals that their

parents brought home.

Shattil spent four years photographing a series of fox families

at the cemetery. She was surprised, the first year, when the

parent foxes split up, just six weeks after the family's six kits

were born. Foxes usually pair up until the kits are grown. Often,

the same pair return year after year to an established den. But

this time, the male fox left with five of the kits and moved to a

different den. The sixth kit stayed with the mother in a den next

to a gravestone.

"What happened? We don't know," Shattil said.

"That sixth kit was small. Maybe it wasn't weaned yet, and

the father took the weaned kits off to another den. I only know

that the second year, a different pair of foxes were back. This

group of foxes, they mixed and matched, a lot. That, or it was a

large extended family. It's not unusual for a female to stay on

another year and help care for her mother's next litter. The

third year, same place, a different team of foxes came back, with

another adult, perhaps a grown kit from the previous year."

She Faithfully recorded their lives, charmed and interested as

she watched the kits grow up. She forced herself to go to the

cemetery, even on days when other projects seemed more

interesting.

"I've learned," she said, "that if you don't go

out, you don't know what you miss.

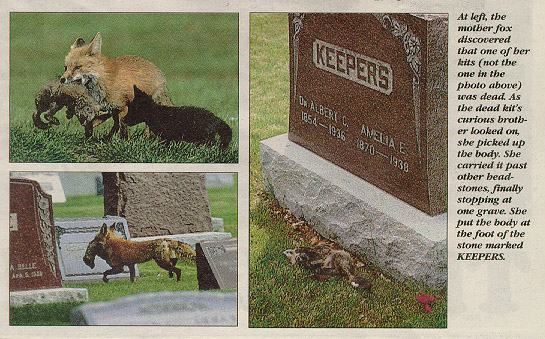

"One day last spring, I didn't feel like going out at all,

but I made myself go. I was watching the mom trot toward the den,

and four black kits exploded out of the den. But I knew there

were five kits in the litter. The mom looked up for the fifth

one. Looked and looked. But the fifth one didn't come out."

The mother went into the den. She

emerged with the fifth kit in her mouth. It hung lifelessly from

her lips. The mother carried the dead kit away from the den. When

one of the kits followed her, she stopped, put down the body, and

waited patiently until the other kit grew bored and rejoined its

brothers and sisters at the den. Then she picked up the dead kit

and trotted on.

The mother went into the den. She

emerged with the fifth kit in her mouth. It hung lifelessly from

her lips. The mother carried the dead kit away from the den. When

one of the kits followed her, she stopped, put down the body, and

waited patiently until the other kit grew bored and rejoined its

brothers and sisters at the den. Then she picked up the dead kit

and trotted on.

Shattil followed, driving her truck slowly along the cemetery

road. She saw the mother pause, and she braked. The mother fox

laid the dead kit at the foot of a gravestone. She paused. Then

she trotted back to the den.

Shattil got out of her truck. She walked over to the gravestone

where the little fox kit lay. The name on the gravestone was

"Keepers."

When she returned the next day, the kit's body was gone.

"It was the saddest thing," she said later. "To

see a behavior like that. Much less photograph it. At this point,

those foxes are part of my family. Their den is just down the

road from my grandmother's. My heart went out to that

mother."

The photographs from that day aren't in "City Foxes."

The book was already at the printer. Besides, Shattil wasn't sure

that such a vivid sequence about death was appropriate for a

children's book.

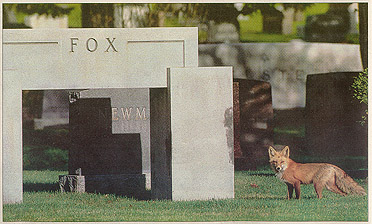

But she wishes that one other photo from the fox project had been

taken before the printer's deadline. She spent days hoping to

photograph a fox alongside a certain tombstone near the place

where the foxes hunt magpies. Always, the fox was just outside

the parameters of the shot Shattil wanted.

Then, finally, it happened: The mother trotted right in front of

the gravestone, just as Shattil clicked the shutter, and she got

her photo.

It is a perfect portrait of a fox looking right into the lens,

with a panting smirk, as it passes the gravestone labeled FOX.

Claire Martin is the staff

writer for Empire Magazine.