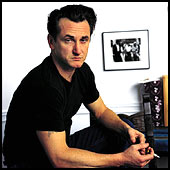

In 'The Thin Red Line' and 'Hurlyburly, Sean Penn makes brutal roles look easy. Just don't ask him how he does it.

Newsweek, December 21, 1998

Sean

Penn really knows how to kill a conversation. Ask him about his new film,

"The Thin Red Line," the first movie in nearly 20 years from acclaimed

director Terrence Malick, opening Dec. 23. "I haven't seen it," Penn says.

"Until I put down my $7 and see it like everybody else, I'm reluctant to

comment." Ask him about the untitled Woody Allen project he just finished

shooting in New York, due for release next fall: "Nuh-uh," he says, with

a definitive shake of his head. Since things are going so well, why not

ask about his ex-wife, Madonna? "Irrelevant!" he exclaims triumphantly.

Sean

Penn really knows how to kill a conversation. Ask him about his new film,

"The Thin Red Line," the first movie in nearly 20 years from acclaimed

director Terrence Malick, opening Dec. 23. "I haven't seen it," Penn says.

"Until I put down my $7 and see it like everybody else, I'm reluctant to

comment." Ask him about the untitled Woody Allen project he just finished

shooting in New York, due for release next fall: "Nuh-uh," he says, with

a definitive shake of his head. Since things are going so well, why not

ask about his ex-wife, Madonna? "Irrelevant!" he exclaims triumphantly.

![]()

Ask Penn enough

questions, and pretty soon you get tired of asking questions. The funny

thing is, that's when he really starts to talk. At first it's just chitchat.

He tells jokes he's picked up from Dylan, 7, and Hopper, 5, his children

with actress Robin Wright Penn. "Did you hear about the brave grape?" he

asks. "An elephant trampled on it full force, and it just let out a little

wine." Then he's discussing, with a tinge of regret, his lack of a formal

education. "I went to auto mechanics and speech at Santa Monica College,

but that's about it," he says. "At least I can articulate the various aspects

of an American-made motor." Pretty soon he's grasping for ways to explain

why it is he won't talk about his movies. "When people talk specifically

about what their characters' intentions were, something gets damaged,"

he says. "I hate it. It's almost like when you give somebody a Christmas

present. If they walk in the room while you're wrapping it, it's not the

same. Part of the present is the surprise. Part of the present is opening

it up."

Penn

may be contrarian, but he's a contrarian with a mission. This Christmas

he's wrapped up two spectacular gifts: not just "The Thin Red Line," in

which he plays a World War II sergeant torn between allegiance to his men

and allegiance to himself, but also "Hurlyburly," a scabrous drama about

the poxed inner lives of four Hollywood sleazebags (Penn, Kevin Spacey,

Garry Shandling and Chazz Palminteri). The films are wildly different--"The

Thin Red Line" is lush and ruminative, "Hurlyburly" adrenalized and brittle.

But they share Penn's esthetic: they're captivating yet emotionally draining,

highly crafted yet doggedly unmainstream. Long hailed as one of the best

actors of his generation,

Penn

may be contrarian, but he's a contrarian with a mission. This Christmas

he's wrapped up two spectacular gifts: not just "The Thin Red Line," in

which he plays a World War II sergeant torn between allegiance to his men

and allegiance to himself, but also "Hurlyburly," a scabrous drama about

the poxed inner lives of four Hollywood sleazebags (Penn, Kevin Spacey,

Garry Shandling and Chazz Palminteri). The films are wildly different--"The

Thin Red Line" is lush and ruminative, "Hurlyburly" adrenalized and brittle.

But they share Penn's esthetic: they're captivating yet emotionally draining,

highly crafted yet doggedly unmainstream. Long hailed as one of the best

actors of his generation,

Penn, at 38,

has reached an amazing new stature: his films are events for the simple

fact that he's in them. Once it was Brando, Pacino, De Niro, Duvall. Today

Penn is the standard of excellence, the untouchable.

But don't think

it's easy for him, hanging out there by himself. Ever since Penn took to

writing and directing, with 1991's "The Indian Runner" and 1995's "The

Crossing Guard," he's been trying to sneak away from acting. "I feel melted

down after every movie," he says. "I love acting. I just want someone else

to do it." He's so good, though--his fearless performance as a death-row

inmate in "Dead Man Walking" got him an Oscar nomination in 1996--that

it's hard to imagine his staying away. "The Thin Red Line" drew him because

of Malick. "Terry makes movies in an unusual way," Penn says, trying not

to unwrap his present too much. "You do half the job and he does the other

half. It has to do with the acting being solid and neutral, so that he

can adapt your character in the editing."

While "The

Thin Red Line" is higher profile, "Hurlyburly," based on David Rabe's stage

play, is actually dearer to Penn. He plays Eddie, a coke- addled casting

director who needs to find a speck of soul in his well of dissolution and

self-loathing. Penn gives his most exquisite meltdown performance to date:

at one point a streetwise chippy, played to tawdry perfection by Anna Paquin,

walks into Eddie's Hollywood Hills condo only to find him shivering in

the pool after failing to drown himself. "How you doing?" she asks innocently.Lip

trembling, Penn

manages

a fractured smile. "I'm a wreck," he answers. "His preparation is extraordinary,"

says "Hurlyburly" director Anthony Drazan. "He gets past his fear to expose

the emotion. It's very courageous, and very raw."

In person, those emotions play similarly close to the surface. At 9 a.m. sharp, Penn walks into Comforts, a cheerful, kid-filled bakery in Marin County, Calif., where he relocated his family from L.A. a couple of years ago. He seems at ease in public: no coat over his head, no aviator shades. One or two moms' heads turn--no big deal. His hair is a bed-mashed pompadour, and his outfit--pointy-toed cowboy boots, SilverTab Levi's, a boating-insignia windbreaker--doesn't quite add up, as if each element were a relic of some bygone character. He gives off an initial sweetness, but unsettling emotions seem close at hand, like the spare cigarette tucked above his ear. He seems like a guy with buttons, most of which you don't want to push.

He talks about his upbringing in L.A., his pull toward acting. His father, Leo Penn, was a blacklisted actor turned director who died in September of cancer at the age of 77. His mother, actress Eileen Ryan, gave up work to raise sons Michael (a songwriter), Sean and Chris (a character actor); she's now happily back at it. "She just did the guest lead on 'Ally McBeal'," her boy says proudly. As a kid Sean hated school, liked to get out of the house. By the end of high school he was working in local theater groups. "I was doing a lot of little plays, but I wasn't getting the parts I wanted," he says. What kind of parts? "Um--bigger parts. I'd open the show, then I'd be backstage for an hour, then I'd do a scene. Next thing I know I'm at curtain call, and I didn't feel like I did anything. I liked to work--the work aspect of things."

By his early 20s, Penn had distinguished himself in "Fast Times at Ridgemont High" (1982), "Racing With the Moon" (1984), "The Falcon and the Snowman" (1985). "You hear talk about people going out on a limb?" says "Fast Times" director Amy Heckerling. "He'll go out on the tiniest twig. He'll go out on a leaf." "Racing With the Moon" director Richard Benjamin recalls Penn's begging to do a dangerous stunt involving a train: "It wasn't a machismo thing. He was worried that the stuntman's body action wouldn't be the same as his--that the audience wouldn't see it the way his character would do it." Around 1985 World War III hit. Penn married Madonna, started slugging photographers and beat guys if they rubbed him the wrong way. In 1987 he wound up in L.A. County jail for a month after violating probation in connection with an assault-and-battery charge. He was a bad-boy cartoon. He calls the punching episodes "a lack of discretion relative to witnesses present" and "entirely justified behavior."

At least he came out the other side. He and Madonna divorced in 1989, and he married Wright in 1996. Today Penn will try to tell you he's peaceful and likes the quiet life on the quiet street with the bakeries and kiddies. It's almost convincing. One thing for sure has changed: Penn has found something healthy upon which to take out his aggression. Something genuinely corrupt and stinky. Something that could use an influx of idealism. Hollywood.

Penn thinks most big, commercial movies are abominable, and he's appalled when talented actors debase themselves in them. "I saw 'Snake Eyes' last night," he says. "It's not just that movie, it's most movies. As damaged as I am, as reckless as I've been, I never murdered my own 'voice.' I think actors s--t on their profession all the time. They can't do a pure movie again, because they carry so much baggage." This is where "Hurlyburly" and bakeries and anger and idealism intersect: at a point of purity, one he's achieved on his own terms. For a moment he's silent. Then he says, "Anything important for me to hold onto, I've held onto." No questions. None needed.

With Devin

Gordon and Yahlin Chang