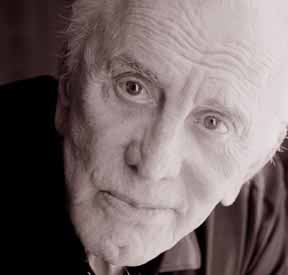

Kirk Douglas, 81, is only nearing his peak in

"Climbing the Mountain", Sep. 18th, 1997

"I have an impediment in my speech," says actor Kirk Douglas.

"I don't have an impediment in my mind."Kirk Douglas is being interviewed about his new memoir, Climbing the Mountain: My Search for Meaning, so a photo- grapher stops snapping the actor's picture long enough to answer the door of the hotel suite.

A newcomer sticks his head in and announces that he works for Douglas' publisher. "I'm with Simon and Schuster," he says, only he speaks far more slowly and loudly than normal: "I'm. With. Si.Mon. And. Schus. Ter." "He's. Your. Pub. Li. Cist," another visitor adds in a loud monotone. "Well, come in," Douglas says. Because Douglas is recovering from a stroke two years ago, the publicist isn't sure he'll remember their meeting months before. But Douglas is no one's fool. "We met," Douglas reminds him in a reproachful tone. "We met when your boss did all the talking. ... I'm glad to see that you talk. I told your boss if he's going to work with me let me see if he talks. Maybe he talks worse than I do." Stroke or no stroke, Douglas is fine.

In fact, if he were any sharper, he'd be ripping the upholstery of the divan on which he's sitting. "I have an impediment in my speech," he says, and invokes the name of God in Hebrew. "I don't have an impediment in my mind."

Yes, he understands why some people are apprehensive when they first approach him. Even his wife occasionally falls into the "speak slowly and loudly" trap. But, surprise: Douglas claims there's a plus side to having a stroke: "You must speak softly and slowly. People listen. They think you're going to say something impor- tant. Also, because you have to speak slowly, you have time to think of what you want to say. You cannot get angry. If I get angry, I cannot speak."

Other than his slow and awkward speech - some sounds are difficult for him to form, he occasionally misses the last syllable of words - there are no obvious signs of physical disability. He's wearing a black sports shirt and slacks tight enough to reveal he remains Spartacus trim. Though his hair is gray, the famous chin cleft is still stark as the Grand Canyon.

He looks and acts at least 20 years younger than a man who will be celebrating his 81st birthday in December. And he hasn't lost his sense of humor. Douglas asks a reporter: "I poured out my soul (for the new memoir). Did you like it? ... Good -- the interview is over."

Douglas, of course, is a three-time Academy Award nominee for best actor. He's made about 80 films, including such classics as Spartacus, Champion, Young Man With a Horn and Lust for Life. He's also published three well-received and best-selling adult novels - Dance With the Devil, The Gift and Last Tango in Brooklyn.

In his first memoir, The Ragman's Son, published in 1988, he wrote about his hellish childhood - as the son of a hard-drinking junk dealer unable to show his children any affection, and a saintly housewife. Young Douglas, the middle and only boy of seven children, grew up in Amsterdam, N.Y., where Jews were banned from working at most local plants. Eventually Douglas went to college, studied acting in New York and achieved stardom, all faithfully detailed in the memoir. The book also revealed Douglas' many sexual liaisons. Now happily married for over 40 years, Douglas smiles. "I wanted to write a book as honestly as I can. I thought of my children reading it. If I didn't (include) disparaging things about myself, they wouldn't believe it. So this is what happened, good and bad.

And I tried to be as honest in Climbing the Mountain." It is a book that begins six years ago, when Douglas was severely injured in a helicopter collision with a small plane. The plane's pilot, 46, and his teen-age student perished. "Why did they die?" Douglas asked himself. "Why was I alive?" To get the answer he returned to his religious roots, studying the Old Testament with several experts. What he found were some great stories. "I said, wow. This is the best script that's ever been written. It's got fratricide, adultery, incest, murder - anything you want is in there. It also has so many dysfunctional families. For a sinner like me, that was reassuring. You learn the most wonderful thing God gave us was free will. We have choices we can make in life."

The Ragman's Son, he says was "where I was, and my Climbing the Mountain is more where I am going." Douglas writes about his growing sense of spirituality, including the importance of giving to charity (he gave away the multimillion-dollar proceeds from the sale of his art collection), and the need to savor the moment. He also ties in many anecdotes about famous people he knew, like Burt Lancaster, Frank Sinatra and Steven Spielberg. Though virtually all his Hollywood contemporaries - including Lancaster, Clark Gable and William Holden - are gone, Douglas claims he doesn't dwell on the passing of an era.

"Listen," he says. "Forty years from now, 50 years from now, a young writer will be saying to an actor, 'You know you are the last of an era.' The eras come and go. I never think of that."

Douglas still sees a lot of movies, but not the way they should be seen. "I usually see movies at friends' houses, because it's more convenient. It's not the way to see a movie. A movie must be seen in a theater with an audience. A regular audience. Not a group of people hoping the movie flops."

Douglas goes on to say that he named his book Climbing the Mountain because he has come to see life as a never-ending quest toward ever-elusive goals. He quotes the poet Robert Browning, saying, "A man's reach should exceed his grasp, or what's a heaven for?" And yes, Douglas says, he has plans for the future.

"Of course. I am a young man. What do you want me to do. Go in a corner and disappear?"

Douglas and his son Michael have been working on a film since before the helicopter accident, a movie further postponed by Kirk's stroke. But young Michael told his dad not to worry. "He told me, 'You'll work with a speech therapist and then we'll do the picture.' "I told him, 'You work with a speech therapist, and when you talk like I talk we'll do the picture.' "

Besides his memoirs and novels, Kirk Douglas is now trying his hand at children's books. His first, The Broken Mirror (Simon & Schuster, $13, 87 pages), is about a young German boy who loses his entire family in Nazi concentration camps. He survives, but when he is liberated he no longer wants to be Jewish. Instead, he tells his American liberators he's a Gypsy. He's brought to the United States and placed in a Catholic orphanage, but it is not until he rediscovers the faith of his childhood that he is able to put his painful war memories to rest. Douglas is donating his proceeds from the book to Steven Spielberg's Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. Douglas says he's been so encouraged by early reaction to The Broken Mirror that he's already at work on a second children's book.

- Curt Schleier