| |

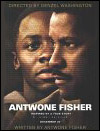

A

BLACK NAVAL OFFICER FINDS PEACE SEARCHING FOR HIS PSYCHOLOGICAL

ROOTS

Antwone

Fisher, a young African American in the U.S. Navy decided

one day to write the story of his life. Ten years later, his

autobiography, with some fictionalization, has now been portrayed

on the screen. The story so deeply touched Denzel Washington

that he decided to direct a biopic, Antwone Fisher,

in which he also plays the role of the psychiatrist, Dr. Jerome

Davenport, who did so much to help Fisher to resolve problems

which not only prompted him to enlist in the navy but also

threatened to get him a discharge for misconduct. When the

film begins, a five-year-old is dreaming about eating pancakes

with his family. When Fisher (played by Derek Luke) wakes

up, a white sailor on a ship in Pearl Harbor soon ribs him

about the color of his face. After Fisher explodes with rage

and his fist, he ends up reduced in rank, restricted to the

base, and required to take three sessions with a naval psychiatrist.

Since he does not believe himself to be "crazy,"

the usual stereotype of a psychiatrist's patient, Fisher at

first shares very little information with Dr. Davenport. To

his credit, and contrary to much current psychiatric practice,

Dr. Davenport decides not to prescribe pills. Fisher, Dr.

Davenport eventually learns, was born in a correctional facility

in Ohio where his mother was incarcerated, and his father

died of a gunshot wound from a girlfriend two months before

he was born. He was then assigned to a foster African American

mother, Mrs. Tate (played by Novella Nelson), who mentally

and physically abused him, calling him "nigger."

His foster mother's teenage daughter abused him sexually,

and one day he ran away to the home of a friend on the block,

but rejecting his foster parent meant that he was next reassigned

to a reform school. When he completed reform school, he was

taken to a shelter, then slept on park benches, and went to

see his boyhood friend. His friend, however, asked him to

accompany him to a foodstore, which his friend unexpectedly

tried to rob; when the proprietor shot his friend, he fled,

and Antwone soon enlisted in the navy. Antwone

Fisher, a young African American in the U.S. Navy decided

one day to write the story of his life. Ten years later, his

autobiography, with some fictionalization, has now been portrayed

on the screen. The story so deeply touched Denzel Washington

that he decided to direct a biopic, Antwone Fisher,

in which he also plays the role of the psychiatrist, Dr. Jerome

Davenport, who did so much to help Fisher to resolve problems

which not only prompted him to enlist in the navy but also

threatened to get him a discharge for misconduct. When the

film begins, a five-year-old is dreaming about eating pancakes

with his family. When Fisher (played by Derek Luke) wakes

up, a white sailor on a ship in Pearl Harbor soon ribs him

about the color of his face. After Fisher explodes with rage

and his fist, he ends up reduced in rank, restricted to the

base, and required to take three sessions with a naval psychiatrist.

Since he does not believe himself to be "crazy,"

the usual stereotype of a psychiatrist's patient, Fisher at

first shares very little information with Dr. Davenport. To

his credit, and contrary to much current psychiatric practice,

Dr. Davenport decides not to prescribe pills. Fisher, Dr.

Davenport eventually learns, was born in a correctional facility

in Ohio where his mother was incarcerated, and his father

died of a gunshot wound from a girlfriend two months before

he was born. He was then assigned to a foster African American

mother, Mrs. Tate (played by Novella Nelson), who mentally

and physically abused him, calling him "nigger."

His foster mother's teenage daughter abused him sexually,

and one day he ran away to the home of a friend on the block,

but rejecting his foster parent meant that he was next reassigned

to a reform school. When he completed reform school, he was

taken to a shelter, then slept on park benches, and went to

see his boyhood friend. His friend, however, asked him to

accompany him to a foodstore, which his friend unexpectedly

tried to rob; when the proprietor shot his friend, he fled,

and Antwone soon enlisted in the navy.

|

Dr. Davenport sees a connection between his childhood experience

and his rage, which emerges twice again while with his navy

buddies. Dr. Davenport also links Fisher's insecurity in courting

an attractive young woman, Cheryl (played by Joy Bryant),

with the childhood abuse, and talking about the problem helps

as much as being with Cheryl, who is very understanding. When

Dr. Davenport feels that therapy sessions are no longer needed,

he implores Fisher to search for his birth-mother so that

he can dissipate the anger that he appears to be reenacting.

Fisher and Cheryl then fly to Cleveland and visit his foster

mother, who supplies him with his birthfather's surname, Elkin;

then the two telephone every Elkin in Cleveland area phonebooks

until they locate Fisher's aunt. His aunt invites him over,

and a family member drives him to meet his birthmother in

perhaps the saddest encounter in the film. His birthmother,

speechless during the meeting, cries after he leaves. When

he returns to visit his aunt, the dream that began the film

comes true--a table set for a king, surrounded by many of

his long-lost relatives and his girlfriend Cheryl. Returning

to Honolulu, he thanks Dr. Davenport for all his help, but

the psychiatrist surprises him by thanking Fisher for enabling

him to save his own marriage. When the film ends, amid audience

applause on an opening night screening in Hollywood, a title

tells us that Antwone dedicated the film to his deceased birthfather.

Few in the audience knew until seeing Antwone

Fisher how locating birthparents (the term used

by adoptees nowadays, rather than the film's passé

terminology about "real" or "natural"

parents) can be so important to someone who feels that he

was once abandoned. The film indirectly can be seen as a plea

for governments in the fifty states to open up records so

that those who suffer psychologically can become whole. More

explicitly, the film is an exposé of what Dr. Davenport

calls "slave mentality," that is, the tendency for

generations of African Americans to engage in ethnic self-hate

by abusing one another, just as they were once abused by their

white masters, a masochistic "identification with the

aggressor" that was identified by Theodore Reich as an

explanation for the transformation of ordinary Germans into

militant anti-Semites after Hitler came to power. Accordingly,

the Political Film Society has nominated Antwone

Fisher as best film exposé and best film

on peace of 2002. MH

|

|